Articles/Essays – Volume 33, No. 1

Plural Marriage, Singular Lives | Todd Compton, In Sacred Loneliness: The Plural Wives of Joseph Smith

Joseph Smith’s polygamous relationships have been a topic of great interest and controversy among Mormons and non-Mormons alike. The reactions of the women whom Joseph Smith took as plural wives and the way in which their relationships with the Mormon prophet were part of their own larger life experiences, however, have seldom been studied systematically. Most writers have contented themselves with making head counts of Smith’s alleged plural wives. The Mormon church historian Andrew Jenson listed twenty seven probable plural wives, Fawn Brodie identified forty-eight, and more recent Mormon historians such as Danel Bachman, D. Michael Quinn, and George D. Smith have identified thirty one, forty-six, and forty-three plural wives, respectively. These lists often do not adequately distinguish between different types of plural wives, particularly between those who probably sustained full connubial relations with Joseph Smith and those who were only posthumously sealed to him “for eternity.”

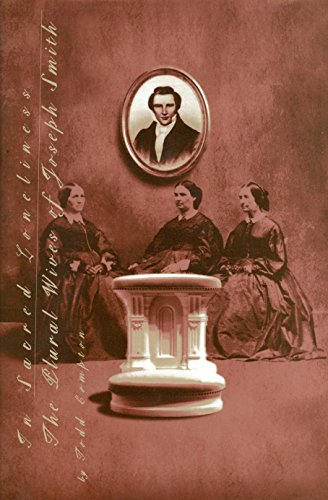

Todd Compton’s massive and path breaking, 788-page study In Sacred Loneliness provides the most comprehensive assessment yet available of the lives of thirty-three women whom he considers “well-documented wives of Joseph Smith” (1). Compton begins with a twenty-three page introduction that dis cusses some of the complex issues that must be addressed if Joseph Smith’s plural marriages are to be understood, and then he briefly summarizes the evidence on each of the wives in chart form. The 596-page core of the book consists of thirty well-written and thoroughly documented chapters that sympathetically reconstruct, using detailed quotations from a wide range of primary sources, the lives of the thirty three women he has identified as plural wives. These include two sets of sisters and one mother-daughter pair whose stories are combined in three of the chapters. Instead of in-text source citations, 148 pages of bibliographic and chapter references are provided. A fifteen page index concludes the study.

Although scholars may take issue with some of Compton’s assumptions and arguments, his study is a major step forward in understanding early Mormon plural marriage. First and most impressively, Compton is concerned about treating each of the women whom he studies as a real person in her own right and reconstructing the entire life stories from birth to death of these often quite remarkable women, many of whom became among the most respected and influential female leaders in pioneer Utah. For many of these women, their relationship with Joseph Smith was only a brief interlude in a much larger and more complex life; for others, the issues of their polygamous relationships with Joseph Smith and, subsequently, with other Mormon leaders such as Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball were a focus of recurrent concern and tension. Compton masterfully reconstructs the often poignant stories of these women without reducing them to stereotypical heroines or victims, as so many earlier accounts have done.

Equally if not more important, Compton has provided in this study the massive primary documentation from widely scattered sources that will allow both scholars and the general public alike to form their own opinions about just what was going on in Joseph Smith’s polygamous relationships and how those relationships affected the women who participated in them. As a non-Mormon scholar, I had the exceptional opportunity of spending more than four months reading primary diaries, journals, records, and affidavits held in the Church Archives in Salt Lake City while working on a study of the early development of Mormon polygamy that eventually would be published as Religion and Sexuality. Only someone who has worked closely with these documents can comprehend Compton’s full achievement in identifying and providing detailed quotations (with exact original spelling and punctuation) from virtually all of the most relevant portions of this substantial corpus of primary materials relating to Joseph Smith’s polygamous relationships and the larger life experiences of these women.

Finally, Compton is to be com mended for candidly trying to come to terms with some of the most knotty and controversial aspects of early Mormon polygamy, including the evidence that Joseph Smith took as plural wives in a full physical sense women who were already married to other men. Compton argues, for example, that “fully one third of his [Joseph Smith’s] plural wives, eleven of them, were married civilly to other men when he married them. . . . Polyandry might be easier to understand if one viewed these marriages to Smith as a sort of de facto divorce with the first husband. However, none of these women divorced their ‘first husbands’ while Smith was alive and all of them continued to live with their civil spouses while married to Smith” (15-16). Compton further points out that “there is evidence that he did have [sexual] relations with at least some of these women, including one polyandrous wife, Sylvia Sessions Lyon, who bore the only polygamous off spring of Smith for whom we have affidavit evidence” (21).

While Compton deserves much credit for tackling squarely and sensitively the thorny issue of these unusual relationships with Joseph Smith, I am extremely dubious about his characterization of them as “polyandrous.” As I have pointed out in Religion and Sexuality, 159-166, and in “Sex and Prophetic Power” (Dialogue 31, no. 4, Winter 1998), I see no evidence that the behavior in which Joseph Smith apparently engaged was viewed, either by the Mormon prophet himself or by his close followers who knew about it, as a form of “polyandry.” Rather, it seems far more likely, given the intensely patriarchal emphasis in early Mormon plural marriage, that such relationships were interpreted as a complex millenarian version of patriarchal levirate polygamy. Even this interpretation, which cannot be de tailed here, may not be sufficient to explain all instances of this kind, however. For example, the most tangled such relationship, that of Zina Diantha Huntington, skillfully analyzed in pages 71-113 of In Sacred Loneliness, suggests the possibility that the demand for total loyalty to the leadership of the prophet and to his will may ultimately be the only way in which some of these relationships can be understood.

Another reservation that I have about this study is Compton’s tendency to state as matters of fact what are, at best, only his own suppositions. This is most apparent in the first paragraph of his chapter on Fanny Alger, the first of the thirty core chapters on Joseph Smith’s plural wives. Compton asserts, without initial qualification in the chapter, that she “was one of Joseph Smith’s earliest plural wives” (25). This is only Compton’s debatable supposition, not an established fact. While contemporary evidence strongly suggests that Smith sustained sexual relations with Fanny Alger, it does not indicate that this was viewed either by Smith himself or by his associates at the time as a “marriage.” The most substantial contemporary de scription of the relationship comes from a letter written by Oliver Cowdery on January 21, 1838, in which he declares that “in every instance I did not fail to affirm that what I said was strictly true. A dirty, nasty, filthy affair of his and Fanny Alger’s was talked over in which I strictly declared that I never deviated from the truth” (38).

There is strong evidence from later sources that Joseph Smith may have considered, at least as early as July 1831, the possibility of reintroducing a form of patriarchal Old Testament polygamy. There is no reliable contemporary evidence, however, that any of the sexual relationships that Joseph Smith may have sustained with women other than his first wife Emma prior to the first formally documented plural marriage ceremony with Louisa Beaman in Nauvoo, Illinois, on April 5,1841, was necessarily viewed at the time as a “marriage.” Such earlier sexual relationships may have been considered marriages, but we lack convincing contemporary evidence supporting such an interpretation. Later Mormon writers simply have assumed that if there was a sexual relationship in volving Joseph Smith, then it must have involved a “marriage.” For this debate as it applies to Compton’s interpretation of Fanny Alger, which first appeared in an article in the Journal of Mormon History 23 (Spring 1996): 174-207, see Janet Ellington’s letter in the Journal of Mormon History 23 (Spring 1997): vi-vii, and Compton’s response in the Journal of Mormon History 23 (Fall 1997): xvii-xix.

From a larger perspective, this and other scholarly reservations that one might have about In Sacred Loneliness are far less significant than the remark able achievement of this study. Just as the superb biography Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith by Linda K. Newell and Valeen Tippetts Avery for the first time presented a full, sympathetic, and well-rounded scholarly analysis of the life of Joseph Smith’s dynamic but much misunderstood first wife, In Sa cred Loneliness provides a thorough, sympathetic, and well-rounded scholarly analysis of thirty-three other women who also sustained important relationships with the Mormon prophet. Anyone seeking to grapple with the complex issues of how Mormon plural marriage originated and what it meant to some of the most articulate Mormon women who participated in the practice will find this study an invaluable starting point.

In Sacred Loneliness: The Plural Wives of Joseph Smith. By Todd Compton (Salt Lake City, Utah: Signature Books, 1997), 824 pp.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue