Articles/Essays – Volume 12, No. 3

Polygamous Eyes: A Note on Mormon Physiognomy

Ruth Benedict perceptively observed: “The first lesson of history . . . is that when any group in power wishes to persecute or expropriate another group, it uses as justification, reasons which are familiar and easily accept able at the time.”[1] Occasionally scientific theories, or ideas masquerading as such, have been used as justification for persecution or prejudice. In such instances, the stature of science has been a particularly effective, though insidious, means of legitimization. During the nineteenth century four of the antecedents of contemporary psychology—mesmerism, physiognomy, humoral psychology and phrenology—were used by their practitioners, journalists, novelists and the lay public to sanction stereotypes of certain racial, ethnic and religious groups.[2]

Each of the four systems of thought was rooted, more or less, in a biological tradition which lent itself to racial explanations by seeming to ground the alleged behavior of unpopular groups in inherent physical characteristics. Even when the group had no uniform national or racial origin, as in the case of Mormons, the cause of behavior was often reduced to some organic source and generalized to the group as a whole.

The application of mesmerism and phrenology to the Mormons has been discussed elsewhere.[3] In this brief note, the popular view of Mormon physiognomy will be considered.

The “Mormon eye” with its mesmeric powers was once as notorious a symbol of Mormonness as the “Jewish nose” of Jewishness. “Glittering eyes,” “piercing looks,” “gaze of the serpent-charmer,” “fascinating eyes,” “eagle eye,” “deep dark eyes,” “terrible eyes,” “fiery eyes,” were all descriptive phrases which added to the fear of Mormons and further associated them with the occult and untrustworthy. A writer tor Harper’s Weekly captured the essence of this theme:

I have never yet seen a Mormon but that something ailed his eyes. They are sunken, or dark, or ghastly, or glaring. There is certainly some mania in all Mormon eyes; none of them can look you straight or steadily in the face.[4]

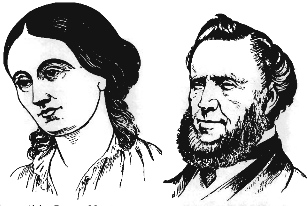

Most of this preoccupation with eyes was a function of the linkage of Mor monism with mesmerism, but physiognomists were equally interested in the Mormon eye. For them it was not the penetrating gaze, glance or stare so much as the shape or relative position of the eye that told the psychological tale. According to one theory, the narrow aperture of the eye was a sure sign of promiscuity. Using something like the method of known groups, Brigham Young’s almond shaped eyes “validated” this theory of wantonness.[5] If Brigham Young was not ample evidence, the theorists listed a set of animals which supposedly displayed similar habits of mating behavior and a corresponding narrow eye opening. “The hog, the wild boar, the dog, the cat, every species of serpent, all of the ape tribes, and all those whose eyes exhibit the almond-shaped opening are promiscuous in their attachments.”[6] Obviously, these animal associations with Brigham Young and his disassociation (shown in Illustration 1 and 2) from a prominent heroine of the nineteenth century, Mrs. Margaret F. Osoli, put Mormons in their place.

Not only Brigham Young, but other Mormon leaders were targets of physiognomic analysis. Some of the descriptions were found in literature, but clearly influenced by the “science” of physiognomy. For example, “The gait of this person [Joseph Smith] was heavy and slouching, his eyes grey and unsteady in their gaze, and his face and general physiognomy coarse and unmeaning.”[7] Another early Mormon leader, Heber C. Kimball, received similar treatment at the hands of a journalist for Harper’s Weekly: “Under projecting eyebrows roll two bright, cunning eyes. Their expression is sly and rat-like, vivid and repulsive. His nose is thick and course; his lips pinched up, and their angles depressed; his head nearly bald, over the crown of which he drags up and plasters down a few straggling hairs.”[8] The “cunning eyes,” “projecting eyebrows,” “thick nose” and “pinched-up lips” had behavioral meaning for the readers of the last century.

Brigham Young was the favorite Mormon target of physiognomy. An anti-Mormon novelist, under the pseudonym “Maria Ward,” credited Brigham Young with “eyes, which changed color with every variable emotion.”[9] Another author noted that Brigham Young’s lower lip and chin “shrank and curled and quivered under feeling.”[10] Still another observed: “His face is indicative of penetration and firmness . . . but his lower lip, if nothing else, eminently betrays the sensual voluptuary.”[11] According to the prominent physiognomist Mary Olmstead Stanton, two traits explained Brigham Young’s influence over his followers: credenciveness and self-esteem. Self-esteem inspired self-confidence and credenciveness made him gullible to unreasonable beliefs.[12] She did detect however, self-will at the root of Brigham’s nose which was “large in all who have excelled.”[13]

Mormon women were no exception to the harsh judgments of the art of physiognomy leveled at the Mormons. The effects of polygamy were clearly written in form and feature of the Mormon woman. A few lines from an article with the provocative title “Scenes In An American Harem” illustrate the point:

I read in her face far more of the secret workings of polygamy than they wished to appear to every idler who might wander through Salt Lake City. On every distorted line of her swollen nostrils, her compressed lips, her lowered eyebrows and her eyes, too hot to weep, was written the fierce agony, the gnawing heart sickness, and the unutterable woe that every true woman must feel, and should feel, who is thus circumstanced.[14]

Furthermore, Mormon women “judging from physiognomical indications . . . belonged to the lowest class of ignorance . . . . The specimens before me were of the wrinkled, spiteful, hag-like order.”[15] Mormon women were homogenized into a monolithic mold. Like the oriental image, individual differences of women were often blurred into a faceless aggregate as de humanization took its toll. One final example captures this homogenization process:

our Briton saw many haggard, weary, slatternly women, with lack-lustre eyes and wan, shapeless faces, hanging listlessly over their fates, or sitting idly in the sunlight, perhaps nursing their yelling abies—all such women looking alike depressed, degraded, miserable, hopeless, soulless.[16]

Physiognomy was called upon to give “scientific” support to negative stereotyping of two other Mormon groups—immigrants and children. The imigrants were portrayed as low-brow, stolid peasants, people of slight intelligence who were represented by the physiognomic clues of narrow brows, slouching posture, open mouths, and vacant stares. The anti-Mormons were adapting the larger nativist stereotyping of unwelcome immigrants. Similar traits were utilized to portray children of polygamous marriages as “neurotic and morons.”[17]

Like blacks, Indians, Jews, Orientals, the Irish, Mexicans and Catholics, the Mormons were stereotyped by the use of theories of behavior popular in the nineteenth century. Unprepared for a pluralistic society, Americans sought and found psychological support for their misconceptions.

In reality, the most compelling factor in the psychological diagnosis of Mormons in the nineteenth century was not to be found in the theories— mesmerism, physiognomy, humoral psychology, or phrenology—but in the attitudes of the practitioners toward Mormons and/or their system of belief. Those who viewed Mormons favorably gave generally favorable diagnoses. On the other hand, those who were unfavorable used commonly available stereotypes. On the whole, the psychological profile of Mormons said more about the attitude of the practitioner than the object of their study.

[1] Ruth Benedict, Race and Cultural Relations. Problems In American Life (Washington, D.C.: National Education Association, 1942), p. 41.

[2] For a brief history of humoral psychology, phrenology and physiognomy, see Gordon W. Allport, Personality (New York: Henry Holt, 1937), pp. 63-85. A short history of mesmerism is found in Theodore R. Sarbin, “Attempts to Understand Hypnotic Phenomena,” in Psychology In The Making, ed., L. Postman (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968), pp. 745-785.

[3] See Gary L. Bunker and Davis Bitton, “Mesmerism and Mormonism,” BYU Studies 15 (Winter 1975): 145-170; and Davis Bitton and Gary L. Bunker, “Phrenology Among the Mor mons,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 9 (Spring 1974): 42-61.

[4] Harper’s Weekly 2 (4 December 1858): 782.

[5] Joseph Simms, Physiognomy Illustrated or Nature’s Revelations of Character (New York: Mur ray Hill, 1887), pp. 158-164.

[6] Mary O. Stanton, Encyclopedia of Face and Form Reading (Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company, 1895), pp. 358-359. Another slightly different theoretical twist follows: “Sensual or polygamous eyes are shown by course, thick, puffy eyelids that are partially closed. The eyes are dull, half-closed and usually discolored.” Harry H. Balkin, How to Measure Your Powers and Increase Your Income (New York: Halcyon House, 1938), p. 176.

[7] Robert Richards, The California Crusoe (London: J.H. Parker, 1854), p. 60.

[8] Harper’s Weekly 1 (11 July 1857): 442.

[9] Ward, 141. Other novelists saw similar ominous signs in Brigham Young’s physiognomy. “He stood on a little hillock, a few feet above his auditors, whom his fiery words held spell bound. He was in the prime of life, of medium stature, but powerfully built, and his face bore the stamp of an iron will to which all must bend, and of that inflexibility of purpose which annihilates all obstacles. His deep-set eyes told of greed, both of money and power, as plainly as the square mouth and heavy jaws revealed the savage in his nature, at once sensual and cruel.” Cornelia Paddock, The Fate of Madame La Tour: A Tale of Great Salt Lake (New York: Fords, Howard & Hulbert, 1881), p. 14. See also p. 26 and Lily Dougall, The Mormon Prophet (New York: D. Appleton & Company, 1899), pp. 17, 31. We are indebted to Greg Ripplinger’s Honors paper on “Physiognomy and the Mormons” for the Paddock and Dougall references.

[10] Samuel Bowles, Our New West (Hartford, Conn.: Hartford Publishing Company, 1869), p. 235.

[11] Harper’s Weekly 1 (11 July 1857): 441.

[12] Stanton, pp. 439, 578.

[13] Mary O. Stanton, Physiognomy (San Francisco: Printed for the author, 1881), p. 97.

[14] Harper’s Weekly 1 (10 October 1857): 650. See Paddock, pp. 24-25 for a similar reference.

[15] Mrs. Benjamin B. Ferris, “Mormons at Home,” in Among the Mormons, ed., W. Mulder and A. R. Mortensen (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1958), p. 263.

[16] Justin M’Carthy “Lochinvar at Salt Lake” Harper’s Weekly 15 (22 July 1871): 675.

[17] “The Effects of Polygamy,” Anti-Polygamy Standard 1 (September 1880).

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue