Articles/Essays – Volume 54, No. 4

Q&A with James Goldberg, Co-founder of Mormon Lit Blitz

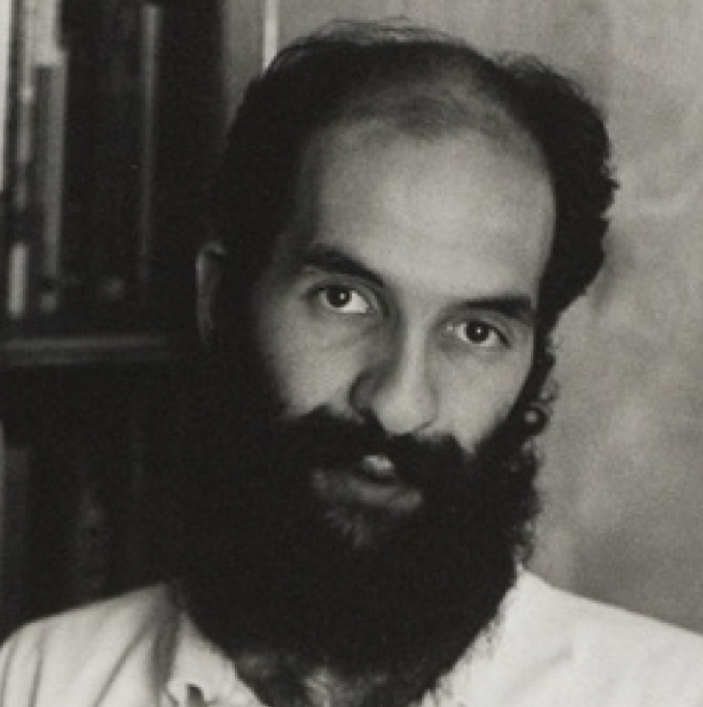

The Mormon Lit Blitz contest has tapped into a rich reservoir of Mormon short-short fiction, reaching a milestone this year with the publication of its first anthology. With a 1000-word limit, final winners selected by a popular vote, and special rounds for translated and translingual work, the contest has yielded a panorama of diverse results during its first decade. Co-founder James Goldberg answers Dialogue’s fiction editor Jennifer Quist’s questions about this ongoing project to advance the reading and writing of Mormon literature.

Dialogue: Some of the Mormon Lit Blitz work has the feel of well-told folklore, as if the contest’s structure, with the pithy word limit and the popular voting phase, encourages this kind of storytelling. Was this part of your original vision?

JG: No. When Nicole Wilkes Goldberg, Scott Hales, and I started the contest, our goal was just to get people to try reading Mormon Lit. We recognized that many potential readers are skeptical about Mormon literature and might not to be willing to wade through a pile of novels long enough to find one they like. We hoped that a three-minute online read would feel low-risk enough that people would give it a shot.

What people have done aesthetically within the Mormon Lit Blitz’s tight length limits has been a delightful surprise. Maybe because writing a very short story or essay is also lower risk for an author, we’ve had a lot of people experiment with form. Kathy Cowley’s “The Five Year Journal” and Luisa Perkins’ “Three Dogs in the Afterlife” immediately come to mind as pieces that have played with shape and style. Citlalli Xochitiotzin’s “Tiempo Una Particula” messes with chronology and narrative perspective in wild ways. And yeah, some people have responded to the length limit by using repetition in structure in ways that evoke folktales: Stephen Carter’s “Slippery” comes to mind. Merrijane Rice’s recent poem “Low Tide” feels very oral to me, with a rhythm deeper than the literal meter of the words. Sarah Dunster’s “Remnant” also has a very grounded, oral feeling for me.

We can’t take too much credit for what people do, of course. If the Mormon Lit Blitz has shown anything, it’s that people can rise creatively to the occasion if there’s an occasion to rise to. It’s so important to give people space to experiment and grow.

Dialogue: You’ve written elsewhere about literature’s power to “enlarge the soul.” Have you seen signs of that happening through the Lit Blitz yet? What has it looked like?

JG: I can’t remember what I’ve said on the subject before, but I’m certainly a believer in the vital role of the imagination in religious life. God speaks to us, so often, through stories. We might as well try to answer once in a while in that same language.

Not every Lit Blitz piece is going to do that for every reader, but Nicole and I find pieces every year that remind us why we’ve kept this work going. Lee Allred’s “Beneath a Visiting Moon” really struck a chord with me: it’s a story I experienced in cascading layers of realizations after I finished. Annalisa Lemmon’s “Death, Disability, or Other Circumstance” was another one that mixed the fantastical, comic, and poignant in a way that’s stuck with me—I also love her story “The Gift of Tongues.” Wm Morris’s “Release” was sunk in for me and stayed. It’s one of those pieces that just tilted my whole worldview sideways for a minute. The cumulative effect of the whole Four Centuries of Mormon Stories contest was really great: it was just so cool to see the sweep of past, present, and increasingly speculative future.

Does that mixture of ideas and feelings and angles count as enlarging the soul? I’m no master of the soul’s geometry, but I think so. It’s looked like, I suppose, just some marks on a screen but for me it’s felt like seeing new worlds I could never have conceptualized all on my own.

Dialogue: Your comments on artistic genius and breaking down barriers between writers and readers seem to favor more connected ways of experiencing literature. I love that, but how have you addressed writers outside anglophone America, less connected to the Mormon literary heartland?

JG: Oh, yes. I am on record railing against the Western trope of the lone artistic genius. I came of artistic age doing theater and I was taught that theater doesn’t exist on the page or even the stage: it’s something you should think of as happening in the air between actors and audience as a viewer’s memories mingle with the experiences of the characters.

I really value the Church and the role it plays in my life. I also love Mormonism, which I have come to think of not as a bounded religious system or a synonym for the restored gospel, but as a shared imaginationscape we are all still helping to expand. I believe that Mormonism, by which I mean that wild mix of theology and speculation and history and experience and jargon that our people has piled up over the years, is richer when everyone is able to contribute. I believe Mormon culture is better when we own, tend, and extend it.

When we finished the 7th Mormon Lit Blitz in 2018, we asked finalists to comment on what they’d like to see in Mormon Lit in the future. And one thing many of them said was that they were interested in more international voices—outside of a few Canadians and one English-speaking Finn, we’d had, to my knowledge, only American finalists in the contest’s first seven years. We launched a Patreon account that same year to help us expand our programming and asked patrons to help us set priorities. They, too, wanted to see a multilingual contest.

Katherine Cowley, a past Lit Blitz finalist who’d also served one year as a coeditor, was the key moving force in turning that aspiration into a reality. Katherine, working with some volunteer translators, developed a multilingual Facebook campaign to solicit submissions. We ended up receiving work in English, Spanish, Portuguese, Japanese, Tagalog, and Estonian and publishing our top picks in both their original languages and an English translation. For logistical reasons, English is still centered in the contest—we didn’t have bandwidth to translate the Estonian poems, for example, into every reader language—but it was an important step and we’re proud we took it. Readers seemed enthusiastic as well: Cesar Medina Fortes, a gifted Mormon essayist writing about his life in Cape Verde, won the reader-selected Grand Prize in that contest.

We continue to think about ways to do more for writers working primarily in languages other than English. We hope our efforts will do well to complement those of other groups, such as the Confradia de Letres Mormonas, in increasing awareness and fostering the continued development of Mormon literary expression outside of English.

It’s a big future. We’re happy to be some small part of it.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue