Articles/Essays – Volume 22, No. 3

Reconciliation

Introduction

So we do not lose heart, though our outer nature is wasting away, our inner nature is being renewed every day. (2 Cor. 4:16)

I come from a religious tradition that does not celebrate the common Christian calendar, other than Easter and Christmas; yet in this portion of my life, I have come to appreciate the religious seasons. I feel the natural rhythm, the conjoining of biological and spiritual impulses with which our earth itself is in organic synchronicity. While I intend to address loving my enemies, in this Lenton season I have sensed a larger theme—reconciliation—of which loving enemies is only a part.

The Preacher tells us,

To everything there is a season,

And a time to every purpose under heaven:

A time to be born, and a time to die;

A time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal;

A time to break down, and a time to build up. (Eccl. 3:1-3)

Increasingly, the latter half of life brings the times of healing and building up. In the first portion of our lives we are appropriately concerned with the external world: forming an ego separate from physical things, parents, and gender identification by rejecting one for another. We select a profession and close the door on other possibilities that interested us. We discover a mate and, with some regret, sever relationships with others. We come to see ourselves as members of a particular family, a tribe, a nation, a discrete religious tradition.

And then, beginning perhaps in one’s thirties and accelerating at mind wrenching, soul-threatening speed in one’s forties, all the lines begin to blur and then disappear. Rather than denning myself negatively—”I am not female; I am not Catholic; I am not black; I am not Russian”—I begin to see that indeed I am all of those things and much more.

For twenty-five years I have written about the nuclear arms race, the dangers of biological and chemical weapons, the need for arms control agreements, and for constitutional restraints upon our propensity to wage executive war thoughtlessly with cataclysmic, inhuman results. I have also spent much of my life working for legal protection of human rights, influenced profoundly as a young man by working with Hubert Humphrey, Roy Wilkins, and Martin Luther King, Jr. These topics continue to be central to my life, and I hope they always will be.

But increasingly I see the need for an inner dimension to match these political efforts. The physical world of law and government is essential but incomplete. Without inner development, we will annihilate each other in one last spasmodic act of human genocide.

Recognizing an inner reality in no way denies the reality and the importance of the objective world. Those philosophies that do make such denials are dangerously unbalanced. For those of us in the West, however, these denials have not been our danger. During the last millennium, we have become masters of our physical environment with a completeness that no earlier age could comprehend through Aristotelian empiricism; Thomistic syllogism; modern science; conscious rational dialogue; and structures of economic, political, and religious power dominated totally by males. Only a handful, furthermore, has comprehended inner reality: mystics of all of the world’s great religious traditions; poets and artists; storytellers who have recorded our inner life in fairy tales, myth, dreams, and ritual; gnostic groups sensing the powerful imbalance of an orthodoxy transfixed with worldly power; and, in modern history, pioneers of depth psychology, preeminently Carl Jung.

But the inner and outer paths have an integral relationship, whether called the ego-self axis, yin and yang, compensation, or thesis and antithesis. Now, as if our globe were indeed one living system, compensating elements are rising simultaneously, not denying the truth of the previous elements but contesting their completeness. A sexual revolution so profound that it can be compared only to the Reformation in its impact is radically changing our very view of the human psyche. Quantum physics hints at an integrated wholeness to our cosmos that obliterates boundaries between space and time, the organic and the inorganic. Brain research reveals an inner cosmos at least as intricate and related. Depth psychology postulates a dialogue between the conscious world of the ego and the unconscious. Whether by contemplation, meditation, dream, or active imagination, we move toward wholeness by bringing to consciousness the compensating messages from the unconscious.

Reconciliation—God Within and Without

All things are of God, who hath reconciled us to himself by Jesus Christ, and hath given to us the ministry of reconciliation. . . .

God was in Christ reconciling the world unto himself, not imputing their trespasses unto them; and hath committed unto us the word of reconciliation.

Now then we are ambassadors for Christ, as though God did beseech you by us: we pray you in Christ’s stead, be ye reconciled to God. (2 Cor. 5:18-20)

For Carl Jung, humankind possesses an inner impulse toward individuation which leads us to seek within ourselves the image of God. This movement compensates for a vision of God as only transcendent, beyond reach, aloof, bleak, occasionally tyrannical, masculine, and thoroughly patriarchal. The immanent God found in our unconscious is both maternal and paternal, warm. By mid-life, petitionary prayers to a transcendent God alone may be so dry, so unrewarding, that a responsive relationship with such a being seems impossible and reconciliation seems presumptuous.

Jung called this view of a transcendent God the “effect of prejudice that God is outside of man,” a “systematic blindness” (1958, 1:482), and explained that for the extroverted West, “grace comes from elsewhere; at all events from outside. Every other point of view is sheer heresy. Hence it is quite understandable why the human psyche is suffering from undervaluation. Anyone who dares to establish connection between the psyche and the idea of God is immediately accused of ‘psychologism’ or suspected of morbid ‘mysticism’ ” (in Dourley 1984, 25).

Jung further observed, “Christian education has done all that is humanly possible; but it has not done enough. Too few people have experienced the divine image as the innermost possession of their own souls” (1953, 308).

Saint Teresa of Avila, a Spanish mystic of the sixteenth century, perceived that vision through a lifetime of contemplation:

Remember how St. Augustine tells us about his seeking God in many places and eventually finding Him within himself. Do you suppose it is of little importance that a soul which is often distracted should come to understand this truth and to find that, in order to speak to its Eternal Father and to take delight in Him, it has no need to go to Heaven or to speak in a loud voice? However quietly we speak, He is so near that He will hear us: we need no wings to go in search of Him but have only to find a place where we can be alone and look upon Him present within us. (1978, 114)

Meister Eckhart, a German mystic of the late thirteenth century, said: “To get at the core of God at his greatest, one must first get into the core of himself at his least, for no one can know God who has not first known himself. Go to the depths of the soul, the secret place of the Most High, to the roots, to the heights; for all that God can do is focussed there” (1941, 246).

The quest for God within ourselves is, I am convinced, the central task of reconciliation. If we worship only the transcendent God, we are cut off from the divinity within our own souls, the image of God shared by all human beings who have ever lived, among all cultures, all religious traditions, all nations under heaven. This cosmic anomie Jung called uprootedness (in Dourley 1984,25).

In a letter to a friend, Jung charted the change that must occur to preserve God’s image within the soul and its terrible importance for our worship and for our being:

Man’s relation to God probably has to undergo a certain important change: instead of the propitiating praise to an unpredictable king or the child’s prayer to a loving father, the responsible living and fulfilling of the divine within us will be our form of worship and commerce with God.

His goodness means grace and light and His dark side, the terrible temptation of power.

Man has already received so much knowledge that he can destroy his own planet.

Let us hope that God’s good spirit will guide Him in His decisions because it will depend upon man’s decision whether God’s creations will continue.

Nothing shows more drastically than this possibility how much of divine power has come within reach of man. (1973, 2:316)

Yet the predominant tradition of a transcendent God, “out there,” wholly Other, has a vital message as well. It warns us against identifying the image of God within ourselves with the objective Person of deity lest we suffer ego inflation and megalomania. Our goal is not to deny the transcendent image without but to seek reconciliation: between the image of God within us all and our worship of the transcendent God.

Reconciliation occurs as we right wrongs in our objective, physical world. Reconciliation also occurs as we heal ourselves within. Finally, reconciliation takes place as we establish a means of dialogue between our objective existence and the world of the unconscious.

Sexual Reconciliation

Neither is the man without the woman, neither the woman without the man, in the Lord. (1 Cor. 11:1)

We have witnessed in the great religious traditions a savage suppression of femininity for at least two or perhaps three millennia. Women have been treated as if they had no souls. At the time of Jesus, women were not allowed to study Torah—the foundational scriptures of Moses. Women, like children and slaves, were not commanded to offer morning prayer. Women, along with children, slaves, and the insane, could not be counted in the quorum necessary for public prayer (Swidler n.d., 2). A daily prayer at the time of Jesus rejoiced: “Praised be God that he has not created me a gentile; praised be God that he has not created me a woman; praised be God that he has not created me an ignorant man.” Leonard Swidler, a contemporary religious scholar and teacher, notes that Paul, sensing the reconciling message of his Master, deliberately provided an antithesis to that daily prayer: “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Gal. 3:28; Swidler n.d., 2).

In the temple at the time of Jesus, women could enter only one outer court, the Women’s Court, five steps below the men’s court. Women in the synagogue were separated from men and were not allowed to read aloud or perform any major public function of worship. In public life generally, a rabbi would refrain from dialogue with women.

Indeed Jesus was a feminist. He gathered women disciples as well as men (Luke 8:1 ff; Mark 15:40 ff). He associated directly and publicly with women in an open, friendly manner. In what must have been a deliberate act, Jesus appeared first to a woman after the resurrection, and Mary Magdalene has announced this awesome event to Christians ever after. This cathedral commemorates her. Jesus’ teachings on divorce (Mark 10:2 ff; Matt. 19:3 ff) were designed to add full personhood to the status of women, who could be stripped of the protection and promises of marriage simply by the husband’s announcement (Swidler n.d., 8).

The attitude of Jesus toward women, contrasted to the severe discrimination of that time, is a model we need to remember today. In comparison, con temporary religious leadership, with notable exceptions, should appear in public only in sackcloth and ashes. I applaud the elevation of Barbara Harris, a black divorced woman, to a bishopric of the Episcopal Church in our own country. She is a beacon for us all.

The American Catholic bishops have led out on issues of great importance during this decade, speaking eloquently and prophetically on nuclear weaponry and economic justice (National Conference 1983, 1986). Catholicism has preserved much that may help us seek reconciliation between men and women in religious life. I am thinking of the honor accorded to Mary, the Mother of God, and other acknowledgments of the numinosity of feminine spirituality recognized in its saints and the religious vocations open to women. Now American Catholics are grappling with the role of women in religious life and ecclesiastical government. I honor this attempt to face the past and come to terms with this enormous self-inflicted wound.

Within my own religious tradition, I long for the time when four black people, three of them women, will sit on the stand as General Authorities at General Conference. No reason exists in Mormon doctrine, I believe, to prevent full priesthood participation by women with every office and calling in the Church being open to them. This profound visual message would transcend in immediate healing power every sermon ever given in our holy house, the Mormon Tabernacle.

Carl Jung taught that we all have within us elements of both masculinity and femininity. Although our psyches seem to form themselves, more or less, congruently with our biological sexuality, I accept the reality of this inner duality. Jung personalized this feminine presence within a male as the anima. Within women the masculine or contrasexual presence is the animus.

I met my anima recently through active imagination. I had previously dreamt of a graying brunette woman, strikingly beautiful. During my imaginative experience, I encountered her again. She seemed to be my guide into the world of the unconscious. She was not the image of God. For me, a male, the Imago Dei is male. But she is my way into subjective spirituality, into those parts of my unconscious mind that are accessible to me. I learned that I could reenter that room in my previous dream at will and converse with the beautiful woman.

Whether in a positive or a negative way, we all project elements from inside ourselves outward, onto people and things in the objective world. We do this positively to learn and to gain perspective by distancing ourselves from our own parts. We do this negatively by projecting characteristics that we will not acknowledge as our own onto another person, then responding with fear, anger, or repugnance.

By withdrawing our projections, we acknowledge elements of our own psyche that have been suppressed unrecognized into the part of our unconscious that Jung termed the shadow. We may acknowledge, nurture, and embrace our animus/anima and our shadow in meditation and in listening prayer and, in so doing, approach our center. The alternative is a psyche dangerously polarized and fragmented. John Sanford, a contemporary Episcopal priest and Jungian analyst, put it this way:

The union of the personality is represented in the imagery of the unconscious as a great love affair. The opposites within us are so far apart that only the great unifying power of eros can bring them together. This can be said to be the common denomination, the basic psychological fact, in all love affairs, and for the person who wishes to become whole it is the great underlying factor that can never be disregarded. (1980, 89)

In 1955, Emma Jung wrote:

In our time, when such threatening forces of cleavage are at work, splitting peoples, individuals, and atoms, it is clearly necessary that those which unite and hold together should become effective: for life is founded on the harmonious interplay of masculine and feminine forces, within the individual human being as well as without. . . . Bringing these opposites into union is one of the most important tasks of present-day psychotherapy. (1955,87)

Jesus taught that we must love ourselves. I am convinced that a vital part of such self-love is our acceptance and love of our contrasexual self. By “love,” I do not mean simply rational dialogue with our unconscious. The anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing understood. “By love may He be gotten and holden; but by thought neither” (1952, 14). For this reason, mystics of all ages often expressed their spiritual union with God in erotic imagery. Witness the Song of Solomon, or the writings of Lady Julian of Norwich.

Our relations with those of the opposite sex are vital to our growth and our loving capacity. But pain may be the cost. Jung noted that marriage, like individuation, was not a course away from pain, but precisely the reverse: “Seldom, or perhaps never, does a marriage develop into an individual relationship smoothly and without crisis; there is no coming to consciousness without pain” (1928, 193). Within and without, the reconciliation of our sexuality is at the center of psychological wholeness, our individuation, awakening with the likeness of God.

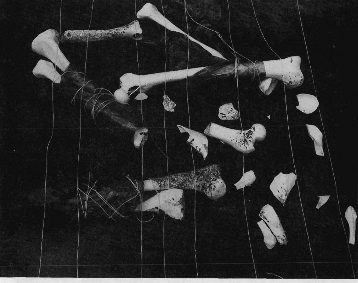

Reconciliation with the Body

What? Know ye not that your body is the temple of the Holy Ghost which is in you . . . ? Therefore glorify God in your body, and in your spirit. (1 Cor. 6:19—20)

Jung offered three profound criticisms of Christianity (Dourley 1984) : its subjugation of the feminine; its denigration of the physical body as inferior to—or less real than—the world of the spirit; and our Manichaean like separation of good and evil without sensing the creative tension in holding this polarity in equipoise. He felt that this deemphasis on physical reality was understandable as the early church did combat with the Roman empire’s de based moral and spiritual values. But without jeopardizing that Christian vision of a moral order, Jung believed we must bring the human body into harmony, finding an equilibrium between spirit and body, discovering both full individuation and the inner image of God.

Jung’s position seems consistent with modern medicine and all we know of human psychology. Repression or denial of our humanity cannot lead to robust spirituality. Early church fathers taught that the human spirit was physical although more subtle or refined than the body. Surely the Christian faith, based on the revelation of an incarnate God, should be the first, not last, to recognize the reality and the holiness of the physical body.

George MacDonald, a Scottish novelist and poet, sensed this a century ago:

It is by the body that we come into contact with Nature, with our fellow-men, with all their revelations of God to us. It is through the body that we receive all the lessons of passion, of suffering, of love, of beauty, of science. It is through the body that we are both trained outwards from ourselves and driven inwards into our deepest selves to find God. There is glory and might in this vital evanescence, this slow glacier-like flow of clothing and revealing matter, this ever uptossed rainbow of tangible humanity.

It is no less of God’s making than the spirit that is clothed therein. (1872, 238)

Unless we believe that our spirit dies in mortal death and then resumes life at the resurrection, what other message did Jesus mean by emphasizing as he did the physical nature of the resurrection? He appeared in a locked room to the disciples and said, “Behold, my hands and my feet, that it is I myself; handle me and see; for a spirit hath not flesh and bones, as ye see me have” (Luke 24:39).

God is our Father and Creator. He made us as we are, our physical bodies no less than our souls. His Son took flesh in a physical body which he repossessed after death, walking, talking, inviting his disciples to touch him, even eating fish with them to cement the point.

George Appleton puts it this way:

It is as a body that I am most aware of myself, and my strongest and most elemental instincts are directed to satisfy the needs and desires of the body. The body is a wonderful organism—breathing, circulation of the blood, digestion and sewage, sexual feeling and the capacity for union and the procreation of children. The body has a marked effect on the feeling tone of its owner. It is an integral part of our being; it is basically good because given us by God. It must be the servant of the total personality through which the person expresses himself in demeanor and behavior. (1976, 15)

Jung says that the unconscious will attempt to compensate for an imbalance in our lives. If we ignore the body, we may experience some form of psycho somatic illness or another attempt by our unconscious to restore the balance. The answer is not to supplant spirituality with licentiousness, nor to deny the body in physical self-abnegation, but rather to reach for a balance in our quest for individuation. By listening to our body, by respecting and loving our body, we allow a dialogue between our physical and spiritual selves so that we may achieve and maintain a balance. This balance is the reconciliation we seek.

Reconciliation and the Subjectivity of Evil: The Love of Enemies

First cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother’s eye. (Matt. 7:5)

I believe that evil, like God, has an objective, transcendent existence. That is, evil exists outside of me. Once in a while we experience consummate evil; Nazi aggressors in World War II, perhaps, represent such external reality. But it seems to me that the subjectivity of evil is far more serious. A Manichaean view of the world as clearly good or clearly evil is difficult to maintain. The War of 1870, World War I, and wars in Korea, Vietnam, Lebanon, Nicaragua, and El Salvador do not allow such simplification. Instead, individual stupidity, greed, and fear—especially fear—were evident in abundance among every faction.

So much that we call evil is a fragment of our own soul—unacknowledged, disowned, and suppressed into our unconscious shadow, there to be projected onto another. Jung explained:

If you imagine someone who is brave enough to withdraw all his projections, then you get an individual who is conscious of a pretty thick shadow. Such a man has saddled himself with new problems and conflicts. He has become a serious problem to himself, as he is now unable to say that they do this or that, they are wrong, and they must be fought against. . . . Such a man knows that whatever is wrong in the world is in himself, and if he only learns to deal with his own shadow he has done something real for the world. He has succeeded in shouldering at least an infinitesimal part of the gigantic, unsolved social problems of our day. (n.d.)

The problem is the paradigm. Do we choose to see the world, and our own souls, as possessing both good and evil, to be held in equipoise; or do we see a battle without quarter or restraint of means to the extermination of one by the other? Here the Catholic Church has wisdom to offer our young Protestant brothers and sisters. Some sorts of wisdom come only through the distillation of time over centuries. Catholic art: paintings and sculpture; philosophy; literature; and tolerance—surely not always present or at least dominant—nevertheless reflect such insight into human foibles and fallibility. One of the early struggles of Christian history was between the Manichaeans and St. Augustine. The Manichaeans saw good and evil as absolutely separate. Augustine was too wise for such single-mindedness. Yet thereafter, we seem in each generation to repeat this same debate.

A wise friend, Richard Rohr (1986), the noted Franciscan retreat master, related the insight of Jesus’ parable of the wheat and the tares, which concludes by instructing the farmer to let the wheat and tares grow together until maturity. From the Sunday school class of my youth, I would have been pull ing up tares in every direction lest I get pimples, hair in unwanted places, and lose all natural body fluids. Now, along with my brother Richard, I see the tares of my youth as the wheat of my life, and surely the wheat of my youth is the tares of my life.

The subjectivity of evil is the psychological reality behind the spiritual principle of loving one’s enemy. Indeed, if we could obliterate evil by a gigantic effort and thereafter live free from pain, grief, travail, and tragedy, and some how progress without pain toward the image of God, we would be fools not to do battle to the death with evil. But it doesn’t work that way.

I do not doubt that a malevolent force exists and means us harm. But I also know that God shapes life to work serendipitously toward our healing and wholeness. Dark forces within us, however unintentional, in dialogue with the self, can produce good. In Goethe’s Faust, when Mephistopheles is asked who he is, he replies, “A part of that power which always wills the evil and always works the good” (in Mclntyre 1941, 91). And Wordsworth said, “A deep distress hath humanised my Soul” (1966, 4:259).

The Book of Mormon prophet Lehi perceived this vision and instructed his son: “For it must needs be, that there is an opposition in all things. If not so, .. . righteousness could not be brought to pass, neither wickedness, neither holiness nor misery, neither good nor bad” (2 Ne. 2:11). He saw the fall of Adam and Eve as premised on this principle: “It must needs be that there was an opposition; even the forbidden fruit in opposition to the tree of life. . . . The Lord God gave unto man that he should act for himself” (2 Ne. 2:15-16).

Swiss philosopher Henry Frederic Amiel said, “Sorrow is the most tremendous of all realities in the sensible world, but the transfiguration of sorrow after the manner of Christ is a more beautiful solution of the problem than the extirpation of sorrow” (1918, 285).

Amy Carmichael’s words are appropriate for our Lenten season, with her double meaning of “lent” intended:

Sorrow is one of the things that are lent, not given. A thing that is lent may be taken away; a thing that is given is not taken away. Joy is given; sorrow is lent. We are not our own, we are bought with a price, and our sorrow is not our own, . . . it is lent to us for just a little while that we may use it for eternal purposes. Then it will be taken away and everlasting joy will be our Father’s gift to us, and the Lord God will wipe away all tears from off all faces. So let us use this lent thing to draw us nearer to the heart of Him who was once a Man of sorrows. (He is not that now, but He does not forget the feeling of sorrow.) Let us use it to make us more tender with others, as He was when on earth and is still for He is touched with the feeling of our infirmities. (1955, 193)

The reality seems to be that the dark and light of our souls are so inextricably blended together that destroying one destroys the other. For Jung, our shadow possesses those characteristics that are integrally our own but that the ego has rejected during its development and socialization. The shadow for Jung is not consummate evil, although evil may proceed from the shadow. Our vitality, our energy, and our power may reside in the shadow along with much of our creativity. As our conscious self, our ego, confronts and acknowledges the shadow, we disarm evil, but we do not obliterate it. Surrender of our shadow’s elements, even if possible, would be disastrous for our peace, objectively and subjectively. Our growth to wholeness as we move toward God’s image demands dialogue, not death.

It is from this understanding that we make sense of the seemingly sense less teaching of every spiritual master: the injunction to love our enemies. When my enemy is within me, I can destroy him only by destroying myself. When my enemy is without, I corrupt myself by using means incompatible with my life to destroy him. Paul admonished that we “not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good” (Rom. 12:21). My enemy possesses characteristics that make him indistinguishable from myself. Even after I destroy him, he will resurrect in yet more fearful form. Nobel novelist Alexander Solzhenitsyn, speaker of uncomfortable truths to both East and West, under stood this point: “If only it were so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the dividing line between good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being, and who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?” (in Forest 1988, preface).

Martin Buber said, “One shall not kill ‘the evil impulse,’ the passion in oneself, but one should serve God with it; it is the power which is destined to receive its direction from man” (1948, 71).

Reconciliation through dialogue is the only way. Jesus taught, “Love your enemies” (Matt. 5:44). Mohandas Gandhi said:

It is easy enough to be friendly to one’s friends. But to befriend the one who regards himself as your enemy is the quintessence of true religion. The other is mere business. . . .

A non-violent revolution is not a program of “seizure of power.” It is a program of transformation of relationships ending in a peaceful transfer of power. . . .

I have only three enemies. My favorite enemy, the one most easily influenced for the better, is the British nation. My second enemy, the Indian people, is far more difficult. But my most formidable opponent is a man named Mohandas K. Gandhi. With him I seemed to have little influence. (1949, 249, 8, 249)

Martin Luther King, Jr., before sealing his witness with his blood, enunciated the same powerful truth: “We will match your capacity to inflict suffering with our ability to endure suffering. We will meet your physical force with soul force. We will not hate you, but we cannot, in good conscience, obey your unjust laws . . . and in winning our freedom, we will win you in the process” (1963,40).

This element—not simply accomplishing a political objective by nonviolence but rather a dialogue with the enemy until enemy becomes friend and both perceive a clearer truth—was the linchpin in Gandhi’s search for truth. It represents the same vital factor of dialogue and equipoise Jung perceived in the inner cosmos of our subjectivity.

Conclusion: Conversion and Reconciliation

Jesus: The kingdom of God is within you. (Luke 17:21)

Buddha: We are what we think. All that we are arises with our thoughts. With our thoughts we make the world, (in Byron 1976)

Albert Einstein: The most beautiful and profound emotion we can experience is the sensation of the mystical. It is the power of all true science. He to whom this emotion is a stranger, who can no longer wonder and stand wrapt in awe, is as good as dead. To know that what is impenetrable to us really exists, manifesting itself as the highest wisdom and the most radiant beauty which our dull faculties can com prehend only in their most primitive forms—this knowledge, this feeling is at the center of true religiousness, (in Barnett 1949, 95)

If humankind has hope—and I believe firmly we do—then transformation must be within or it will never happen without. Monsignor William H. McDougall, a Roman Catholic clergyman, sensed this need for transformation. In the revised edition of his second book, By Eastern Windows, he noted, “All of the values we are promoting in [the American Catholic Bishops’ Peace Pastoral] letter rest ultimately in the disarmament of the human heart and conversion of the human spirit to God” (in Weigand 1988).

Carl Jung observed the same:

Today humanity, as never before, is split into two apparently irreconcilable halves. The psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate. That is to say, when the individual remains undivided and does not become conscious of his inner contradictions, the world must perforce act out the culprit and be torn into opposite halves. (1953, 9:70-71)

For Jung, the answer was individuation: a state of compensatory dialogue between the ego and the unconscious that propels us toward the image of God. I would use the more conventional religious term of conversion. Without con version or individuation no legal or governmental constraints in the objective world can save us from destruction. The outer world simply reflects the recon ciliation—or its lack—within. In that sense, subjectively we create the ob jective world:

The great events of world history are, at bottom, profoundly unimportant. In the last analysis, the essential thing is the life of the individual. . . . This alone makes history, here alone do the great transformations first take place, and the whole future, the whole history of the world, ultimately springs as a gigantic summation from these hidden sources in individuals. In our most private and most subjective lives we are not only the passive witnesses of our age, and its sufferers, but also its makers. We make our own epoch. (1953, 10:149)

But Jung held out hope for such transformations, beginning within each in dividual. “The afternoon of humanity, in a distant future, may yet evolve a different ideal. In time, even conquest will cease to be a dream” (1953, 11:493).

Albert Schweitzer also spoke to that hope:

We are no longer content . . . to believe in the Kingdom that comes of itself at the end of time. Mankind today must either realise the kingdom of God or perish. The question before it is whether we will use for beneficial purposes or for purposes of destruction the power that modern science has placed in its hands. So long as its capacity for destruction was limited, it was possible to hope that reason would set a limit to disaster. Such an illusion is impossible today, when power is illimitable. Our only hope is that the spirit of God will strive with the sprit of the world and will prevail. . . .

The miracle must happen in us before it can happen in the world. . . . Nothing can be achieved without inwardness. The spirit of God will only strive against the spirit of the world when it has won its victory over that spirit in our hearts, (in Mozley 1950, 107-8)

Hermann Hesse reminds us Christians that this phenomenon exists in every serious religious tradition:

What then can give rise to a true spirit of peace on earth? Not commandments and not practical experience. Like all human progress, the love of peace must come from knowledge. .. . It is the knowledge of the living substance in us, in each of us, in you and me, of the secret magic, the secret godliness that each of us bears within him. It is the knowledge that, starting from this innermost point, we can at all times transcend all pairs of opposites, transforming white into black, evil into good, night into day. The Indians call it “Atman,” the Chinese “Tao,” Christians call it “grace.” When the supreme knowledge is present (as in Jesus, Buddha, Plato, or Lao-Tse), a threshold is crossed beyond which miracles begin. There war and enmity cease. We can read of it in the New Testament and in the discourses of Gautama. Anyone who is so inclined can laugh at it and call it “introverted rubbish,” but to one who has experienced it his enemy becomes his brother, death becomes birth, disgrace honor, calamity good fortune. Each thing on earth discloses itself twofold, as “of this world” and not of this world. But this world means what is “outside us.” Everything that is outside us can become enemy, danger, fear and death. The light dawns with the experience that this entire “outward” world is not only an object of our perception but at the same time the creation of our soul, with the transformation of all outward into inward things, of the world into the self. (1971, 59-60)

Before consciousness is undifferentiated unity. Then comes separation into consciousness as we assert an identity apart from God. There follows further fracturing as we separate not only into conscious and unconscious parts, into worlds of objectivity and subjectivity, but yet farther apart as male and female, body, intellect, and spirit. Then in the physical world we subdivide endlessly into family, tribe, race, nation, and religious tradition. But finally a reconciliation begins.

Call it what you will—conversion, individuation, a rise of social con sciousness—it is here that reconciliation between polarities occurs. Charles Peguy, a French writer, observed, “Everything begins in mysticism and ends in politics” (1943, 109). We discover the integral unitary system that comprises the physical cosmos and the interior of our soul. Unification of the physical world and the world of psyche and spirit is not something we need to accomplish, only something we need to discover.

We may make this discovery through compassionate service in the objective world, as have Dorothy Day, Mother Teresa, and Martin Luther King. Such service teaches us our enormous common humanity that dwarfs the vital but less central characteristics distinguishing us. We sense our common aspirations, our human needs and impulses, and the stamp of divinity within us that makes us brothers and sisters and propels us toward God. We may make the same discovery by meditation and contemplation, comprehending God’s image at our center, or by Jungian depth psychology, by which our conscious self or ego enters into dialogue with those parts of our personal unconscious available to us through dreams, meditation, Christian and non-Christian mysticism. Archetypes of the collective unconscious, which possess the numinosity of God, communicate with our ego to compensate for the one-sidedness of the latter, attempting to provide a gyroscope of the spirit as we proceed toward individuation and a realization of the image of God.

Thomas Merton, perhaps this century’s most profound and most honored Christian mystic, described this journey in the traditional language of interior Christianity, from St. John of the Cross, St. Teresa of Avila, and Lady Julian of Norwich, to Meister Eckhart, Jacob Boehme, Evelyn Underhill, or Dag Hammarskjold.

After an early period of contemplative life in the Trappist abbey in Gethsemani, Kentucky, memorialized in his brilliant early autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, Merton experienced conversion. His record of this occasion is a classic in Christian confession, every bit as honest, insightful, and numinous as the best of St. Augustine in his Confessions. Merton had gone from the abbey in Gethsemani to Louisville, the nearest city, for medical treatment:

In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the centre of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed by the realization that I loved all these people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness, or spurious isolation in a special world, the world of renunciation and supposed holiness. The whole illusion of a separate holy existence is a dream. . . . This sense of liberation from an illusory difference was such a relief and such a joy to me that I almost laughed out loud. .. . It is a glorious destiny to be a member of the human race, though it is a race dedicated to many absurdities and one which makes terrible mis takes: yet, with all that, God Himself gloried in becoming a member of the human race. A member of the human race! To think that such a commonplace realization should suddenly seem like news that one holds the winning ticket in a cosmic sweep stake. . . . There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun. . . . There are no strangers. .. . If only we could see each other [as we really are] all the time, there would be no more war, no more hatred, no more cruelty, no more greed. .. . I suppose the big problem is that we would fall down and worship each other. . . . The gate of heaven is everywhere. (1966, 156-58)

Other mystics have clothed the same thought in different words. Francis Thompson, a Victorian English poet, wrote:

The angels keep their ancient places;

Turn but a stone, and start a wing!

‘Tis ye, ’tis your estranged faces,

That miss the many-splendored thing.

But (when so sad thou canst not sadder)

Cry—and upon thy so sore loss

Shall shine the traffic of Jacob’s ladder

Pitched betwixt Heaven and Charing Cross. (1965, 349)

Leo Tolstoy recorded his own conversion in words reminiscent of Richard Rohr’s rendition of the parable of the wheat and tares.

Five years ago, I came to believe in Christ’s teaching, and my life suddenly changed; I ceased to desire what I had previously desired, and began to desire what I formerly did not want. What had previously seemed to me good seemed evil, and what had seemed evil seemed good. It happens to me as it happens to a man who goes out on some business and on the way suddenly decides that the business is unnecessary and returns home. All that was on his right is now on his left, and all that was on his left is now on his right. (1921, 103)

John Woolman, an American Quaker in the nineteenth century, rejoiced:

While I silently ponder on that change wrought in me, I find no language equal to convey to another a clear idea of it. I looked upon the works of God in this visible creation, and an awfulness covered me. My heart was tender and often contrite, and universal love to my fellow creatures increased in me. This will be understood by such as have trodden the same path. Some glances of real beauty may be seen in their faces, who dwell in true meekness. (1910, 6-7)

This then is our quest. From unconscious unity to the pain of conscious ness and separation, out of the Garden of Eden into consciousness and moral responsibility, then back into a union that never really ended. Just days before his death, Merton said, “We are already one, but we imagine that we are not. What we have to recover is our original unity” (1973, 308).

We seek reconciliation within, which allows reconciliation without. Within and without become one as I pull into myself all that is without. Within my own soul I become male and female, Mormon and Catholic, Jew, Muslim, and Hindu, Soviet and American, black, brown, and white.

Remember Gandhi’s instructions to the Hindu who had murdered a Muslim after the murder of his own wife and child. Gandhi instructed the shattered man to adopt and raise a Muslim child—but to raise the child as a Muslim. Thus the shattered man might become whole.

Love is not found in creeds or ideas but in people. The inner journey allows ecumenicism because it cannot prevent it. No church or religious tradition stands at the entrance as the protector and definer of orthodoxy when the door is in my own soul. Hence we effortlessly pass over obstructions to unity in the objective world. Merton said, “It is my belief that we should not be too sure of having found Christ until we have found Him in that part of humanity that is most remote from our own” (in Forest 1988, 25).

In this Lenten season we pray for reconciliation throughout our globe and within the cosmos of our souls. This is the message of the intercessory prayer of Jesus:

Neither pray I for these alone, but for them also which shall believe in me through their word;

That they all may be one; as thou, Father, art in me, and I in thee, that they also may be one in us; that the world may believe that thou hast sent me.

And the glory which thou gavest me I have given them; that they may be one, even as we are one. (John 17:20-22)

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue