Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 1

Reinventing Mormonism: Guatemala as Harbinger of the Future?

With the assistance of her family, Marta Angelica Solizo forms and paints incredibly detailed ceramic Nativity scenes. A standard set con sists of fourteen pieces: three sheep, a bull, four donkeys laden with corn, squash, flowers, firewood, three wise men with a flute, a ceramic pot, and a colorful bag; and, of course, Jose, Maria, and the baby Jesus lying in a manger. The appeal of this assortment derives from its local character exemplified in the brightly colored, hand-woven textiles adorning the Mayan figurines.[1]

The Solizos have taken an internationally recognized religious icon, the Nativity, and given it local immediacy. This translation of meaning from the international to the local level expresses both affinity and difference with international Christianity. Affinity is present in the recognizable characters of the three wise men, Jose, Maria, Jesus, and the animals. Difference is apparent in the Mayan features, textiles, flute, firewood, flowers, squash, and corn.

A similar movement or a cultural translation from the international to the local level in Mormonism is the focus of this essay.[2] I contend that Mormonism in Guatemala is being locally reinvented. Cultural translation can be observed through a variety of avenues. One particular example is a public assertion by a Guatemalan Mormon of an ethnic difference with Euro-American Mormons. This claim is examined with insights from anthropological literature on ethnicity. Comparable avowals of ethnic distinction by Native American Mormons are highlighted. A second avenue of cultural translation can be seen in Guatemalan interpretations of the Book of Mormon and the Popol Vuh in the context of Guatemalan nationalism.

Moving from the particular to the general, I will consider finally the implications of local reinventions of Mormonism in a rapidly growing international church. Recent assertions of a Mormon ethnicity by scholars in the United States are analyzed in relation to ethnic distinctions affirmed in Guatemala to suggest that rapid growth is reshaping Mormon ism at its center as well as at the periphery. The emerging international gospel is increasingly lived locally by individuals trying to make sense out of a globally interconnected world. In the next century claims of an ethnic Mormon identity will continue to be made by those uncomfortable with the changing character of Mormonism; but they will be countered by an uneasy attachment to an international gospel adapted to a variety of local cultures.

Covenant of Abraham

Dramatic episodes often reproduce historical understandings, ethnic identities, and perceptions of existing power relationships.[3] An event I observed in Guatemala included a public assertion of likeness and difference that evoked both past and future in terms of the present.

While seated in the chapel of a colonial style LDS meeting house in Antigua, Guatemala, I was participating in a weekly meeting of the all male lay priesthood.[4] Luis (a pseudonym) was teaching a lesson on the Abrahamic covenant. In the midst of the discussion Luis turned to me and explained that what distinguished Latin American Mormons from Anglo-American Mormons was the fact that the former were direct descendants of Abraham through the peoples of the Book of Mormon, while “los americanos” or “los anglos” were adopted into the Abrahamic covenant.[5] This view was echoed by others in the group, and subsequent discussions indicated that a similar view was held by many Latin Americans.[6]

According to the LDS Bible Dictionary, the covenant God made with Abraham promised that his descendants would be offered the blessings of salvation through baptism, the priesthood, exaltation through celestial marriage (thereby eternal increase), certain lands as an eternal inheritance, and that Christ would come through their lineage. Those of non-Israelite heritage, gentiles, could also become heirs to the covenant but only through the ordinances of the gospel.

Ethnic Identities

Valuable insights can be obtained by exploring the singularity of ethnic identity professed by the participants in Luis’s priesthood quorum discussion. The use of theories of ethnicity, however, must be qualified. First, the identity asserted by Luis was constructed in a Mormon community. Second, it blurs distinctions among Mayas, Ladinos, and Euro Americans that make up the membership of the Antigua ward.[7] Third, this event involved individual (as opposed to group) expressions of an ethnic identity. Finally, although the claim made in this priesthood class might be widely shared, there are likely Guatemalans who would dispute it as strongly as a North American might.

Notions of self are often manifested through relationships with others.[8] Luis’s pronouncement of an exclusive primordial connection to the Abrahamic covenant was made as a direct challenge to my presence, an apparent Euro-American Mormon, in a Guatemalan priesthood quorum.[9]

An ethnic identity “involves symbolic construals of sensations of likeness and difference.”[10] Luis was asserting an identity that distinguished himself, as a Guatemalan with Native ancestry, from me, a Euro American, while simultaneously professing a likeness with me through our shared Mormon religion. Ultimately, he recognized, all Mormons share in the blessings of the covenant of Abraham. Yet for Guatemalans and others with Native ancestry, these blessings have a primordial quality; they are given at birth.

Luis, a Ladino, was claiming an identity that blurred the distinctions among Maya, European, and African descent. His claim is similar to that of Guatemalan nationalists, primarily Ladinos, who assert a connection to the Mayan past as part of their national identity. The Mormon context in which it is formed, and thereby its lack of salience outside of the church, makes Luis’s claim peculiar in Guatemala. Yet in the church it provides Mayas and Ladinos with a shared identity which also encompasses, through adoption, Euro-Americans.

Ethnic identities gain salience both symbolically and socially[11] Guatemalan discourse about the Book of Mormon and the Old Testament might be understood as a form of social validation of these texts, akin to engaging them as myths of origin. This dialogue is not unlike discussions of the Doctrine and Covenants and the oral narratives, known as pioneer stories, for Mormons in the United States with pioneer ancestry. Integral to ethnic identity is the perception of shared descent which Guatemalan Mormons maintain through stories of the Old Testament and the Book of Mormon.[12] For example, Guatemalans can and do refer to Abraham, Lehi, Sarah, Nephi, or other Old Testament and Book of Mormon figures as grandparents, thus claiming a parent/child relationship (over many generations).[13] Guatemalans look to the distant past, as they interpret it through the Book of Mormon, to establish an identity with salience in the present.[14]

Not only does this postulated connection with Abraham link Guatemalan Mormons with a past, it also links them to a future. The Book of Mormon offers some key assurances to the house of Israel. The book fore tells that in the latter days the restored gospel will go first to the gentiles (who can be interpreted as Euro-Americans in the United States) and then: “when the Gentiles shall sin against my gospel … I will bring the fullness of my gospel from among them. And then will I remember the covenant which I have made unto my people, O house of Israel, and I will bring my gospel unto them” (3 Ne. 16:10-11).

When combined with primordial attachments to the Abrahamic covenant, this scripture can be interpreted in a manner that might lead to serious social consequences. Similar claims proved divisive in the mid 19303 in Mexico. Approximately one-third of Mexican Mormons, known as the Third Convention, petitioned the Utah hierarchy for local leader ship, missionary programs for Mexican children, educational opportunities, translation of all doctrinal literature, and the opportunity to do temple work.[15] Their requests were based in part on the special position, derived from the Book of Mormon, which they believed those with Native American ancestry held in the church. In a letter written in November 1936 J. Reuben Clark, a member of the First Presidency, denied Mexican requests and warned members of the Third Convention that they did not have an exclusive share in the blood of Israel.[16]

In 1989 similar assertions of ethnic difference were a point of contention in a letter from George P. Lee to the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve. Lee, a Navaho, was the first Native American to have served as a general authority. Shortly after writing this letter, Lee was excommunicated for “apostasy” and “other conduct unbecoming a member of the church.” He had written:

My beloved Brethren, I am afraid that you as Gentiles or “adopted Israel” have forgotten your blessings and the divine role you were to play. I am afraid that the same thing that has happened to the Nephites is happening to you. … I feel that you are sinning against God. … [Because] You have set yourself [sic] up as a literal seed of Israel when the Lord Jesus designated you as Gentiles or “adopted Israel.”[17]

In the current social context Guatemalan Mormons such as Luis are asserting an identity that transcends their marginal position in relation to the hierarchical center of Mormonism. Through the evidences of rapid growth in Latin America, scriptural promises, and a primordial ethnic attachment to Israel and ancient America, Guatemalan Mormons, in a manner reminiscent of distinctions claimed by the Third Convention and by George P. Lee, translate their marginal position in the church to one of primary significance by invoking the past and the future. Although the volatile actions of the Third Convention and of Lee were socially peripheral even among Native American Mormons, the public assertions of ethnic difference I observed in Guatemala suggest that the basis for such divisive claims may have been symbolically central.

The Book of Mormon and the Popol Vuh

An ethnic affinity with Abraham and the communities in the Book of Mormon involves more than the consideration of primordiality or adoption. Guatemalan Mormons with Native ancestry repeatedly profess the belief that the Book of Mormon is a record of their progenitors who dwelled in the land that they still occupy.

This canonical account of ancient American civilizations is employed as a new source for meanings socially attached to the numerous temples, pyramids, stela, and palaces that dot the Guatemalan landscape. Through retelling Book of Mormon stories, Guatemalans can imagine their ancestors living amidst the grandeur of these spectacular edifices. For example, some members told me that the ruins of Kaminaljuyu, near Guatemala City were the vestiges of the city of Zarahemla (from the Book of Mormon). For those few who could afford to do so, a visit to the ancient Mayan cities of Tikal, Quirigua, Kaminaljuyu, or Copan is comparable to the pilgrimages to the Mormon historical sites of Nauvoo, Inde pendence, Kirtland, or Palmyra made by Mormons in the United States.

The Guatemalan Mormons I interviewed unanimously claimed that there were many similarities between the Book of Mormon and the Popol Vuh, a Quiche Mayan epic recorded in the sixteenth century by a Quiche noble.[18] The Popol Vuh, which has been incorporated into the rhetoric of Guatemalan nationalism and is required reading in public schools, has obtained local significance for Mayas and Ladinos alike.[19] Guatemalan members told me that although the names of the people and places were different, both books spoke of the visit of Jesus to the Americas, gods, wars, the tower of Babel, Creation, Trinity, and Satan. While the Popol Vuh is closely tied to sites that are still identifiable, the lack of continuity between Book of Mormon place names and modern Guatemalan place names permits converts to Mormonism to exercise more fluidity in their postulated attachments to sacred places.[20]

Jesus was explicitly identified by Guatemalan Mormons with the Sovereign Plumed Serpent in the Popol Vuh. Although today scarcely a trace of the Sovereign Plumed Serpent can be found in Quiche oral narratives, he played a major role as one of the gods covered by the terms Maker, Modeler, Bearer, and Begetter in the creation stories and historical narrative of the Popol Vuh. Guatemalan converts to Mormonism have conflated the Sovereign Plumed Serpent, a local god revived by Guatemalan nationalists, with the internationally recognized Jesus Christ, whose ancient visit to the Americas is proposed in the Book of Mormon.

Anthropologists and sociologists usually refer to this type of symbiotic reinvention as syncretism. William Madsen has defined the process of syncretism as “a type of acceptance characterized by the conscious adaptation of an alien form in terms of some indigenous counterpart.”[21] In Guatemala such an adaptation is clearly taking place. Yet the indigenous counterpart from which this syncretism has emerged has more in common with the rise of Guatemalan nationalism than with an ancient Mayan tradition. The Popul Vuh has been adopted as a nationalist text by the Mayan past in the present. Both the Book of Mormon and the Popul Vuh are written sources which are assigned a greater importance than oral narratives which evolved as a discourse of resistance against colonial subjugation over nearly 500 years since the recording of the Popul Vuh in a latin script. Socially and symbolically, Guatemalans can claim something most other Mormons lack: a sacred local manuscript they believe complements the imported religious text of the Book of Mormon.

Blanca y Deleitable

In contrast to the argument proposed here, David Martin has suggested that conversion to Mormonism in Latin America involves an ex tensive re-socialization that cuts converts off from almost all outside connections and substitutes an orientation to the United States that might be described as a religious vehicle for making Latins into North Americans.[22]

Martin is correct that conversion to Mormonism in Latin America in volves intense pressures for resocialization in which aspects of American ism are prevalent. He is wrong, however, in suggesting that Mormons succeed in transforming Latins into North Americans. A closer investigation reveals that Mormon affinity with the lands of the Americas is primarily interpreted by Guatemalan Mormons in the context of rising Guatemalan nationalism. Nonetheless, tensions between adaptation and conformity lie just beneath the surface.

Mayan communities have been assaulted for five centuries by authorities attempting to instill Catholicism. Yet the failure of the use of force to produce complete conformity is apparent. Catholic edifices are built on top of Mayan temples. Prayers during La Fiesta de Santiago reveal that Mayas pray to their own gods alongside Catholic saints.[23] In Santi ago Chimaltenango Mayas imbue their patron saints with images of their own “Mayanness.”[24]

Obviously, the methods of conversion employed by Mormon missionaries and by Spanish conquistadors and missionaries cannot be credibly equated. For Guatemalans today, the most of effective means to resist Mormon missionaries is to turn the missionaries away or simply to ignore them. A significant percentage of Guatemalans does just that. A few, however, listen to the message and join the church.

Many Guatemalans who embrace this new gospel believe that their ancestors wrote the Book of Mormon, that the Popol Vuh supplements this canonical text, that the significance of the Maya in the past and future of the church exceeds their temporary marginality; and they imbue Lehi, Sa rah, Nephi, and other Book of Mormon characters with their own “Mayanness.” In fact, the Book of Mormon serves not only as another testament of Jesus Christ but also as a new witness of the Sovereign Plumed Serpent. This slippage in translation should not be dismissed with the assertion that Mormons are making Latins into North Ameri cans. Such a claim presents Latin Americans as passive actors in the onslaught of American imperialism and ignores the complex ways that Latin Americans engage and resist Mormon penetration. In his discussion of Mormonism, Martin has failed to recognize that “ideological hegemony is not monolithic and static, fully achieved and finished, but constantly renegotiated.”[25]

Despite the above qualifications, neither should Martin’s assertions be entirely dismissed. With rejection as a more effective means of resistance, the local reinvention of Mormonism is not yet as apparent as that of Catholicism. Adaptation lies beneath an overt expectation that Latin converts become like North Americans, racially and culturally, a transformation anticipated in Mormon scripture. A comparison of the English and Spanish translations of key Book of Mormon verses elucidates such tension.

In the Spanish translation, the prophet Nephi proclaimed that when “los gentiles” bring the Book of Mormon to the posterity of his family that “las escamas de tinieblas empezardn a caer de sus ojos; y antes que pasen muchas generaciones entre ellos, se conviertirdn en una gente blanca y deleitable.”[26] In contrast to this Spanish translation, the most recent English version no longer promises that the descendants of the Book of Mormon people will become “a white and delightsome people.” Since 1981 that phrase has been changed to “a pure and delightsome people.” Similar references in other verses, however, have been maintained in both the English and the Spanish accounts.[27] Both versions anticipate a transformation—one racial and cultural, the other only cultural.

Despite the force of such statements in both the English and Spanish versions of the Book of Mormon, it would be incorrect to assume that the same meaning is attached by both Guatemalans and Mormons in the United States. To speculate that the meanings of “blanca” and “white” are completely equivalent is to ignore the discursive space into which the term is thrust in Spanish. Martin errs when he imagines that a North American expectation of cultural or racial transformation is accomplished without acknowledging multiple possible interpretations. A more complete picture of the contextual meanings of this phrase in Guatemala and elsewhere in Latin America is required. The complexity of the Guatemalan responses to the Abrahamic covenant and the Book of Mormon, brought to light here, casts doubt on the assumption that Latins are being turned into North Americans.[28]

Nonetheless, Martin does bring to light a troubling paradox in the exportation of Mormonism from the United States. Latin American Mor mons are caught between the anticipations of many Mormons in the United States that they are “Lamanites” (the “dark-skinned,” “savage,” and “wicked” scourge of the white people in the Book of Mormon) and simultaneously are culturally white. This haunting expectation is tragically demonstrated through the experience of an Argentine woman now living in the United States. She has complained to me that, although she has no Native ancestry, she is consistently identified as a “Lamanite” because she speaks with a Spanish accent. Contrary to the assumptions of her Mormon peers, she is just as Euro-American as any Mormon in the United States. Her experience draws attention to the inaccuracy of Mormon stereotypes of Latin Americans as well as illuminates the paradox projected on Latin American Mormons: that one ought to be but cannot quite be white.

If a white woman from Argentina cannot be considered “white” by her Mormon peers in the United States, then the challenge for a Maya or Ladino in Guatemala must be insurmountable. This attempt by Guatemalans to highlight affirmations of difference with Euro-Americans should not be interpreted as an extension of the stereotype that Guatemalan converts cannot quite be “white.” Rather, it is the fallacy of this expectation of racial and cultural conformity that I wish to convey. This essay is not so much about Guatemalan or Latin American Mormons as it is an attempt to explicate and publicize the criticisms that Guatemalans have made of “the forces that are affecting their society—forces which emanate from ours.”[29]

When Martin emphasized a Latin American Mormon orientation to the United States, he could have been referring to this paradoxical expectation to become “white.” In fact, six of the people I interviewed, including Luis, have lived in the United States for extended periods of time and probably operate competently in either the United States or Guatemala. Such people, who could be described as living between two cultures, do hold disproportionate authority in the local congregation. North Ameri can cultural expectations, on the other hand, should not be assumed to have the same meaning in Guatemala as they do in the United States. In fact, these transcultural Mormons were the ones who most strongly affirmed to me their own contrast with Mormons in the United States.

The local reinvention of Mormonism in Guatemala is not a wholesale repudiation of its roots in the United States. Guatemalans reach back to a distant past, interpreted through the rhetoric of Guatemalan nationalism, to create a sense of continuity with an imported religion in the present. Primordial attachments to the Abrahamic covenant, a fascination with the Popul Vuh, and Book of Mormon prophecies of a glorious future for the Native peoples of America serve as symbolic means for Guatemalans to transcend a temporary position of marginality in the church. Luis and other Guatemalans have taken aspects of a globally interconnected world and given them local meaning in a manner reminiscent of Marta Solizo’s Nativity scenes. Although the Nativity is unmistakably Christian, the Mayan clothing and gifts display local elegance and would have been just as appropriate for the Sovereign Plumed Serpent as for Jesus Christ in ancient America.

Ethnic Mormons

To emphasize the significance of the present in the social construction of Mormon identities, and to bring this discussion from particular events in Guatemala to general transitions in the church as a whole, I draw from recent assertions of ethnic Mormonism in the United States. Changes at the center of Mormonism, I contend, are accompanying recent peripheral growth.

The supposition that Mormons “represent the clearest example to be found in our national history of the evolution of a native and indigenously developed ethnic minority” was originally proposed by Thomas O’Dea in 1957.[30] Mormon ethnicity, according to Dean May, was based on a series of experiences which Mormons shared. The belief that Mormons were a “chosen people” in a promised land, several migrations in the Midwest and then to Utah, persecution, hardships, struggling for survival in the Great Basin, distinctive doctrines and folk narratives all served to mold an ethnic identity for Mormons. May acknowledged in 1980 that the ethnic model for Mormon identity was already suspect because of rapid growth in the twentieth century. In defending his position, he pointed to the dominant role of the central leadership based in Utah and the frequent external ostracizing of converts as factors that contribute to a constant revitalization of Mormon distinctiveness.

Since 1980 the church has more than doubled in size. Diversity is rapidly reshaping Mormonism.[31] Despite the growing variation in the church, private skepticism and even open speculation about doctrines, history, and authority are met with increasing hostility as part of a process that Armand Mauss has called sectarian retrenchment.[32] This development threatens the internal and external viability of an ethnic Mormon identity, as contrasted with a fundamentalist sectarian one. Recent exhortations by church leaders to preach the gospel and strengthen the members expose inherent tensions which proselytization and diversity produce with an ethnic Mormon identity given at birth.

In response to such developments, claims of a Mormon ethnic identity are receiving renewed emphasis. Despite his September 1993 excommunication, historian D. Michael Quinn claimed: “I’m a DNA Mormon.”[33] In a subsequent address at Snow College in Ephraim, Utah, he said, “I’m still a Mormon for the same reasons that secular Jews are still Jewish.”[34] In the Tanner lecture at the 1994 Mormon History Association’s annual conference, Patricia Nelson Limerick, a non-Mormon with Mormon ancestry, proposed using the Mormons to rethink ethnicity in American life by arguing that Mormons could still be regarded as an ethnic group.[35] The same subject occupied a subsequent panel discussion on “Ethnicity in Mormon History.”[36] During that discussion the question “Do you consider yourself an ethnic Mormon?” was posed to the audience. A majority said yes.

These self-identifications can be analyzed in much the same manner as I have just done above with the identity asserted by Luis in Antigua. The Anglo Americans at MHA claimed a shared descent and assert a connection to a past and a future in terms of the present. The past that lays the groundwork for such declarations of singularity can be found in narrative form in pioneer stories and family histories and in written form in the New Mormon History.[37] These stories evoke a sense of a shared past for Mormons of pioneer ancestry.

It should not be surprising that claims of Mormon ethnicity gained new immediacy after recent disciplinary actions were taken against prominent scholars and/or feminists. The position of the skeptical scholar and/or feminist in the current climate of the LDS church is precarious. These assertions from within the scholarly community challenge the right and ability of church leaders to strip people of their Mormon identity. They affirm an association with a past and a future that cannot really be taken away but seems precarious. Such assertions must be understood in their temporal context. The past and future evoked are given meaning in the perilous present.

Two of the major thrusts of the current retrenchment produce a polarizing tension with assertions of Mormon ethnicity. While promoting “an expansion and standardization of the missionary enterprise,” church leaders also place a “renewed emphasis on temples, temple work, and genealogical research.”[38] A vital complement to temple work is the writing of family histories. Genealogy and family histories serve to reinforce a sense of group distinctiveness among multi-generation Mormons, while the rapid growth that is a product of the expanding missionary effort threatens that distinctiveness.

In addition to the direct effects of retrenchment, Mauss argues, an in direct consequence “has been a further undermining of Mormon identity.” Mormon identity has unintentionally been eroded by Correlation, characterized by “centralized, standardized, and top-down managerial control.” For example, the consolidation of meeting schedules into three hour blocks on Sundays has led to a dramatic decrease in the week-long, community building activities of previous Mormon generations.[39]

In the first half of the twentieth century, Mauss noted, “the social boundary between insiders and outsiders was more often drawn by the non-Mormons than by the Mormons.”[40] With the decreased salience of geography, politics, or social distance in the second half of the century, “many Mormons have found it necessary to draw their own boundaries from the inside.”[41]

While pioneer stories lack a clear immediacy in Guatemala, nationalist rhetoric and archaeological evidences of a glorious Mayan past provide an alternative immediacy for the Book of Mormon and the Popol Vuh. Mormon identity in Latin America, as in the United States, is formed locally by individuals drawing upon internationally significant ideas. The most striking aspect of these two divergent ethnic assertions by Luis in Guatemala, and by certain scholars in the United States, is that they are each drawn primarily from the inside. While the Popol Vuh and alternative interpretations of the Abrahamic covenant are generally unknown among Mormons in the United States, the identity asserted by Mormons in the United States has no immediacy for the first-generation converts who are coming primarily from foreign countries.

Despite the lack of salience that a Mormon ethnicity presumably holds for most new members of the church, some applicability for con verts has also been suggested. After claiming to be a “DNA Mormon,” Quinn added, “This is true for converts as well as those who are born into the church.”[42] While the adoption of converts into ethnic Mormon ism appears possible from Quinn’s perspective, the Guatemalan converts have inverted this assertion of a peculiar ethnic Mormonism by denying Euro-Americans a primordial claim to the covenant of Abraham while yet allowing for their adoption into the covenant. Each identity claim draws its immediacy from the local environment. Each expresses both difference and similarity with an emerging international Mormonism. The Mormon ethnicity discussed by O’Dea and May was primarily based on the external creation of boundaries between Mormons and non-Mor mons in the United States. These recent assertions of ethnicity, however, also depend on boundaries drawn from the inside.

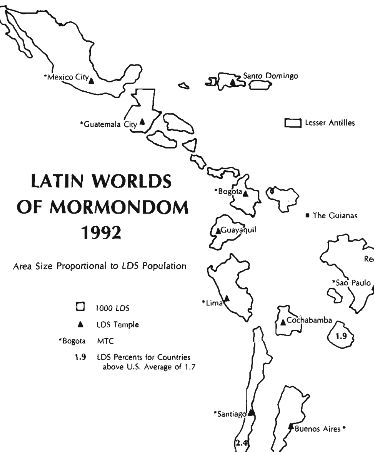

Turn of the Century

In this essay I have focused on the local adaptation of Mormonism. I have stressed the enduring reinvention of Mormonism through the consistent re-evaluation of the past and future in terms of the present. In building this argument I have pointed particularly to Guatemalan expectations for a glorious future. Latin American membership in the LDS church has already increased from 22,503 in 1960 (1.3 percent of the entire church) to 2,397,000 in 1992 (29.5 percent of the entire church).[43] If these numbers indicate a continuing trend over the next few decades, then the expectation of a leading role for the Latin Americans has the potential of fulfillment, although it will be somewhat constrained by the dominance of centralized authority.

No Guatemalans with whom I spoke used ethnic difference as a socially divisive tool. It is unlikely that they were aware of any similar assertions of an exclusive primordial claim to the Abrahamic covenant or any unhappy consequences thereof. Most of the demands of the Third Convention have now become standard practice in the church, and it is consequently unlikely that a similar schism is brewing in Guatemala. Yet a fertile symbolic distinction lies just beneath this quiet surface. The Third Convention, George P. Lee, and a priesthood leader in Guatemala have all symbolically invented the rhetoric of Mormon ethnicity in a manner that emphasizes the primacy of Native Americans in a “white” church.

Numerous unofficial statements by U.S. church leaders have included claims that Euro-Americans can be and often are literal descendants of Israel.[44] The Book of Mormon, however, repeatedly states that the gospel will be restored first to the gentiles and only subsequently to the house of Israel (1 Ne. 13-15, 22; 2 Ne. 10, 29-30; 3 Ne. 16, 28:27, 29:1; Mormon 3:17; Ether 12:23, 36). Some of the statements of church leaders, largely unavailable in Guatemala, appear as if they might contradict various passages in the Book of Mormon. A productive climate for varying local interpretations is thereby created. Increased access to translated works in the next century could lead to a revision of some local interpretations or to some contention over orthodoxy; but most likely the co existence of multiple points of view will increase along with the size of the church.

The expanded avenues of communication and transportation that made possible the rapid post-World War II growth of the church continue to evolve. New technologies have made for further advances in mass communication. However, when emerging technology has been combined with rapid growth in the past, interpersonal communication with the upper levels of church leadership has dramatically diminished. The handshakes that signified bonding during the numerous community building activities at the beginning of this century are being replaced by video images and written statements read from the pulpit. This emerging form of communication frequently moves only from the top to the bot tom. Attempts to use new technology in a manner that allows for more personal forms of communication might, in the future, help to forestall individual or local resort to symbolic differences as fodder for socially disruptive actions.

Conclusion

Mayan and Ladino converts in Guatemala, as well as Mormons in the United States, take aspects of the globally interconnected world and give them local meaning. The international gospel of the late twentieth century finds a local immediacy in Guatemala through Book of Mormon stories imbued with “Mayanness” and correlated with the Popol Vuh; and in the western United States through folk narratives and family histories. Assertions of Mormon ethnicity resound with difference as well as with community. As the next century approaches, the words of Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson gain new resonance in Mormonism: “We need to give up naive ideas of communities as literal entities; but remain sensitive to the profound ‘bifocality’ that characterizes locally lived lives in a globally interconnected world, and the powerful role of place in the ‘near view’ of lived experience.”[45]

When communication proceeds primarily from the top down, slip page in translation is more likely. Slippage is not necessarily problematic, as long as it is recognized as legitimate. The ceramic baby Jesus which forms the focal point of Marta Solizo’s Nativity scene is honored, not threatened, by the Mayas surrounding the manger. Their gifts, though equally appropriate for the Sovereign Plumed Serpent, are not rejected by the family of Jesus. Mormonism in the next century is apt to be increasingly characterized by diverse understandings of what it means to be Mormon. Diversity can be fostered or it can be suppressed, but it will never disappear.

[1] This essay is based on three months of observation and interviews with dozens of Mormons and Catholics in Antigua, Guatemala, and surrounding communities I conducted from May to August 1993. The research was funded in part by the Stanley Foundation at the Center for International and Comparative Studies at the University of Iowa, the University of Iowa School of Religion, and Roy and Nadene Murphy of Sugar City, Idaho. I appreciate the help and insights of Kerrie Sumner Murphy, Charles Keyes, Armand Mauss, and David Knowlton.

[2] Peter Lineham has argued that there is a cultural translation involved in the adoption of Mormonism in other cultures. See “The Mormon Message in the Context of Maori Culture,” Journal of Mormon History 17 (1991): 62-93. For a discussion of translation in Catholic conversion, see Vincent L. Rafael, Contracting Colonialism: Translation and Christian Conversion in Tagalog Society Under Early Spanish Rule (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993).

[3] Michael Roberts, “Ethnicity in Riposte as a Cricket Match: The Past for the Present,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 27 (1985): 420. See also Clifford Geertz, The Interpre tation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973).

[4] This meeting combined the elders and high priest quorums, which would ordinarily meet separately in the United States.

[5] Luis had spent some time in the southwestern United States and had apparently picked up the use of the term “anglo” to refer to Euro-Americans. He also employed the more common Guatemalan term “americanos.”

[6] This particular assertion was not explored in my formal interviews and consequently more research is needed to establish with any accuracy just how pervasive it is.

[7] Within the category of the Maya (or Indios) there are also locally significant divisions such as Quiche, Mam, etc. A discussion of the impact of these differences in the church would require more fieldwork. The term ladino is a local term for people of mixed ancestry and for Mayas who have adopted the Spanish language and no longer identify with an indigenous community. See Richard N. Adams, “Guatemalan Ladinization and History,” The Americas, Apr. 1994,527-43. The term Euro-American is my term for people of European ancestry from the United States and is intended to correspond with Luis’s use of “los angles” and “los amer icanos.”

[8] Harold Isaacs, The Idols of the Tribe (New York: Harper and Row, 1975).

[9] Luis was unaware of my partial Iroquois ancestry.

[10] G. Carter Bentley, “Ethnicity and Practice,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 29 (1987): 27.

[11] Anna Maria Alonso, “The Effects of Truth: Re-Presentations of the Past and the Imagining of Community,” Journal of Historical Sociology 1 (1988): 33-57.

[12] Charles F. Keyes argued that “what is common to all ethnic groups is not any particular set of cultural attributes but the idea of shared descent.” See “Towards a New Formulation of the Concept of Ethnic Group,” Ethnicity 3 (1976): 206.

[13] For the significance of parent/child relationships, see Charles F. Keyes, “The Dialectics of Ethnic Change,” in Charles F. Keyes, ed., Ethnic Change (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1981), 5.

[14] For a discussion of the significance of the past and future in ethnic identity, see George De Vos and Lola Romanucci-Ross, “Ethnicity: Vessel of Meaning and Emblem of Con trast,” in George De Vos and Lola Romanucci-Ross, eds., Ethnic Identity: Cultural Continuities and Change (Palo Alto, CA: Mayfield, 1975), 364.

[15] Most members of the Third Convention eventually reconciled with the centralized authorities in Utah and returned to the LDS church. A few followers of Margarito Bautista, however, remained autonomous.

[16] F. LaMond Tullis, Mormons in Mexico (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987), 137- 68.

[17] Copies of the letters that George P. Lee sent to the press after his excommunication have been widely circulated. I have a copy in my possession. See also Mike Carter, “Mormon Officials Excommunicate General Authority,” Salt Lake Tribune, 2 Sept. 1989, Bl-2.

[18] See Dennis Tedlock, trans., Popol Vuh (New York: Touchstone, 1985).

[19] The majority of people I interviewed did not finish school. The average attendance was between six and twelve years. About a third of them had actually read Popol Vuh. A couple of members had devoted extensive time to studying the Popol Vuh, but the assertions by the majority of the members were assumed rather than developed.

[20] From a historical perspective, however, the validity of correlations between the Book of Mormon and the Popol Vuh is undermined by the stark differences between the phys ical environments described in each account. While the animals and plants depicted in the Popol Vuh include numerous local species such as monkeys, pumas, jaguars, coatis, tapir, pos sum, macaws, whippoorwills, parrots, quetzals, yellowbites, corn, beans, squash, matasanos, jocotes, and chilis; the Book of Mormon, usually in general terms, refers to beasts, dogs, fish, fowl, serpents, insects, grain, grass, corn, and herbs while substituting some non-native varieties not found in the Americas until after 1492, such as ass, cattle, horse, elephants, sheep, oxen, swine, barley, oats, rye, and wheat.

[21] William Madsen, “Religious Syncretism,” in Manning Nash, ed., “Social Anthropol ogy,” in Robert Wanchope, ed., Handbook of Middle American Indians (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1967), 6:333-56.

[22] David Martin, Tongues of Fire: The Explosion of Protestantism in Latin America (Cam bridge, MA: Basil Blackwood, 1990), 209.

[23] David Carrasco, Religions of MesoAmerica (San Francisco: Harper, 1990).

[24] John M. Watanabe, “From Saints to Shibboleths: Image, Structure, and Identity in Maya Religious Syncretism,” American Ethnologist 17 (1990): 131-50.

[25] Alonso,48.

[26] 2 Nefi 30:6, El Libro de Mormon (Salt Lake City: La Iglesia de Jesucristo de los San tos de los Ultimos Dias, 1980). The post-1981 English version reads: “their scales of darkness shall begin to fall from their eyes; and many generations shall not pass away among them, save they shall be a pure and delightsome people.”

[27] This change seems to have been made because the 1840 edition of the Book of Mormon was changed to read “pure,” a change not maintained in subsequent editions. Neither the 1840 nor 1981 editions changed similar references. See 1 Ne. 2:23; 2 Ne. 5:21-24; Jacob 3:8; Alma 17:15; and 3 Ne. 2:15.

[28] See also Thomas W. Murphy, “Are Mormons Turning Latins into North Americans? The Hot/Cold Dichotomy and Word of Wisdom in Guatemala,” unpublished manuscript, 1995.

[29] Michael Taussig, The Devil and Commodity Fetishism in South America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980), 6.

[30] See Thomas O’Dea, The Mormons (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957). This particular passage was quoted in Dean May, “Mormons,” in Stephan Thernstrom, ed., Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1980), 720-31.

[31] Daniel Golden, “Diversity Reshapes Mormon Faith,” Boston Globe, 16 Oct. 1994,26.

[32] Armand Mauss, The Angel and the Beehive (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

[33] “Six Intellectuals Disciplined for Apostasy,” Sunstone 16 (Nov. 1993): 68.

[34] D. Michael Quinn, “Dilemmas of Feminists and Intellectuals in the Contemporary LDS Church,” Sunstone 17 (June 1994): 68.

[35] Patricia Nelson Limerick, “Peace Initiative: Using the Mormons to Rethink Ethnicity in American Life,” Journal of Mormon History 21 (Fall 1995): 1-29.

[36] David C. Knowlton, Mark L. Grover, Mario DePillis, and Patricia Nelson Limerick, “Ethnicity in Mormon History,” panel discussion at the Mormon History Association conference, Park City, Utah, May 1994.

[37] See the essays in D. Michael Quinn, ed., The New Mormon History: Revisionist Essays on the Past (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1992).

[38] Mauss, 85.

[39] Ibid., 167.

[40] Ibid.,xii.

[41] Ibid., 167.

[42] “Six Intellectuals,” 68.

[43] Deseret News, 1993-1994 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1992).

[44] See Bruce R. McConkie, Mormon Doctrine, 2d Ed. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1965); Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, 3 vols., comp. Bruce R. McConkie (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1956), 3:246; Joseph Fielding Smith, comp., Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1976), 149-50.

[45] Akhil Gupta and James Ferguson, “Beyond ‘Culture’: Space, Identity, and the Poli tics of Difference,” Cultural Anthropology 7 (1992): 11.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue