Articles/Essays – Volume 07, No. 1

Revolution and Mormonism in Asia: What the Church Might Offer a Changing Society

About the time this publication was going to press, a team of expert Asian scholars from Brigham Young University were setting out to examine the educational needs of the members of the Church in Asia. This was only one among several efforts to adapt the program of the Church to the needs of non-American cultures. Here Professor Paul Hyer explores revolutionary trends in Asia and makes a positive assessment with regard to the role the Church can play in the lives of the Asian people.

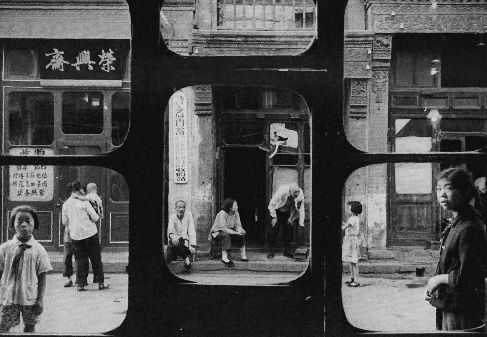

Asia is a land of revolution, a land where a complex of revolutions are inter related in such a way that one phase is not understood independent of the others, nor of the traditions from which they stem. These revolutionary trends are creating rapid changes throughout Asian society, one of which is a search for a new stability, and this greatly influences the development of Mormonism in Asia, including the kinds of people it attracts and its relative success or failure in sustaining activity and building a strong organization.

Mormon missionaries thrust into this turbulent culture preach what appears to some Asians to be just another version of Christian doctrine, but what is, in fact, a radical and revolutionary Christianity. The principles and programs of the Church embody a total value system, a unique way of life which can help reintegrate in new form or function certain important aspects of Asian tradition. In the following discussion I propose to treat some ways in which the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is relevant to modern development in Asian societies. First, however, it may be useful to establish the background which will lend perspective to these developments and to the role of the Church in Asia.

Traditional Asian societies have had a high level of integration and stability and have maintained a phenomenal resistance to change, as, for example, in the family-centered society of old China and the caste system of India. This century, however, with the advance of modern science, institutions, and ideas, has seen the disintegration of most traditional Asian societies. In China, this has amounted to the virtual collapse of a civilization and the rise of iconoclastic communism. The chaos resulting from dynastic decline, warlordism, civil war, invasion, and a century of semicolonial status have created great social and political ferment, and this has, in turn, led to a new formative period, which many Asians feel may merge into a whole new cultural synthesis.

Although similar revolutionary movements have taken place in Western society, they have done so over longer periods of time and under much different conditions from those which exist in Asia. What took centuries to happen in the West has happened in a single generation in Asia. Japan was ushered forcibly into the modern world by Perry’s American fleet; China began the process, still incomplete, during the Opium War; India, Indonesia and other nations were subjugated by European powers involved in voyages of exploration and discovery. From one point of view, the tragedy of the coming of the modern West was Asia’s subjugation by a civilization which discouraged the preservation of age-old Asiatic customs. China’s Confucian society was largely the model and prototype for much of the social structure and culture of Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. But the great stability of imperial China, the glory and sophistication of its traditional culture, also proved to be its curse by retarding its adjustment to the modern world. Upon encountering the West/all the great nations of Asia have passed through various stages of rebellion, restoration, reform, and revolution. In the wake of the disintegration of their traditional cultures, they are still searching for a new synthesis, a new value system, a viable integration of elements from their old culture with those of the modern world.

What are some of the problems of Asian societies as they emerge from traditional ways of life to the complexities of the modern world, and how can the gospel of Jesus Christ and the programs of the Church assist in solving them? For one thing, as people move to a relatively individualized and independent existence, they invariably lose the security and stability of their former family-centered social relations. In this most important area, Asian converts may benefit immensely by an acceptance of the gospel. In the modern development of China and Japan, for example, many young people cut loose from the moorings of traditional society have in their frustration sought security without success in new ideologies and in the fraternity of the communist party or other radical organizations.

Another common phenomenon, anomie (“A social vacuum, marked by the absence of social norms or values”), occurs with a breakdown of social values and the disintegration of society; when this happens, peasants become strangers and aliens in their own country. If one studies the composition of such new religions as Soka Gakkai in Japan or Cao Dai in Vietnam, one generally finds an anomie group of people seeking new security, new stability, and new ties, people who turn to “nativistic” religious movements and “revitalization” sects which try to bridge the gap between the familiar ways of tradition and the strange ways of the modern world. Such movements seldom appeal to the intellectuals of Asian society.

Asians can well be served by the organization and programs of the Restored Church as individuals find new ties in the branch or ward family and in the fraternity of priesthood quorums and auxiliary organizations. The father image of a branch president or bishop as a confidant and counselor is even more important to young Asians than to Western youth who have been conditioned to lead comparatively more self-reliant or independent lives. Asians are accustomed to making fewer friends than most Westerners, but these friend ships are generally stronger or more intimate. The common bond of the gospel is an excellent foundation for a warm, trusting friendship. Thus, in a number of ways, Asians find in the Church a new security, both spiritual and social, a security often superior to the older, more narrow way because it brings them into closer contact with the present world. The security of the old family system was too often based on economic necessity and involved a strong element of fear. New Latter-day Saint converts in Asia, as elsewhere, find a security hopefully within the family, but based on the love, mutual respect, and spiritual enlightenment gained from the gospel. In addition, the reception through the Church of the Holy Ghost, the “Comforter,” is the source of a deep inner security which will meliorate the chaos and confusion so often character istic of a rapidly developing nation.

Another frustrating problem inherent in Asia’s move into the modern world is that new alternatives create an increasing need for the making of choices. Under the old, comparatively simple way of life, a person had but to faithfully follow established ways of doing things, which changed little from generation to generation. These sacrosanct traditional ways gave the individual security but little freedom. Such customary behavior inevitably fell victim to modernization, and traditionally oriented persons were invariably torn by the dilemmas and the frustrations of making decisions. It was natural, under these conditions, that many would seek a reliable index to truth, a measure of proper behavior, and a direction in life which would promote real success. The gospel introduces to people the gift of discernment by the Spirit, personal revelation on individual problems, and special counsel and guidance available through the contemporary oracles of God. Many Asians bear testimony to a new-found purpose and direction in the gospel plan. They find new models for living in successful, well-adjusted members of the Church.

A third problem to vex Asians as they are liberated from feudalistic traditions is the increasing involvement in a world of ever-expanding desires—the “revolution of rising expectations.” The compulsion is generally to acquire more and more material goods and services, regardless of prior economic standards. This phenomenon has long been a way of life to most people in “advanced” societies, but the full impact of materialism is quite new to Asians, who have been conditioned for centuries to an austere lifestyle. Certainly gaining a few creature comforts above the level of subsistence is no sin, but the problems of materialism in modern society are very real to a people inclined to live by bread alone, to strive unwittingly to gain the world in exchange for their soul, or to sacrifice family for professional development and social status for a rather unenlightened use of newly gained individual freedom.

No definitive prescription or detailed analysis can be given here about the gospel’s significance for those caught in a dilemma between traditional poverty and modern materialism, but Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans of my acquaintance seem to find a solution in the self-discipline of the teachings of Jesus introduced to them by the missionaries. They find an enlightened individualism and a self-fulfillment in dedicating their time, means, and talents to brothers and sisters in a common cause.

Within the program of the Restored Church, Asian converts seek to find a better life for the people of their nations while avoiding such abominable alternatives as Tokyo’s hedonistic night life and shallow materialism or the oppressive controlled consumption of Peiping’s totalitarian puritanism. They find that “man is that he might have joy,” a joy born of faith, intelligence, love, justice and the wise use of one’s powers. They learn that true happiness is not found merely in more and more goods and services but that, as Joseph Smith taught, “Happiness is the object and design of our existence, and will be the end thereof, if we pursue the path that leads to it; and this path is virtue, uprightness, faithfulness, holiness and keeping all the commandments of God.” The Church, then, helps Asian converts to mark out the most fruitful path for life and to avoid tangents which, while inviting, dam the way to true progress and happiness.

Another problem faced by many Asians is that of identity in relation to conflicting roles, a problem similar to the “identity crisis” faced by some people in advanced, complex societies. Formerly Asians had a relatively high degree of consistency of roles in the limited cycle of their traditional life. But within the short span of a generation, the number of roles played by individuals in the complex round of modern life has burgeoned. The gospel assists Asian converts in resolving tensions between their various roles. Central to this is the under standing of oneself as the direct offspring of Diety. Asians, more contemplative and introspective than their Western counterparts, find great security, hope, self-confidence, and direction in the new self-image they find in the gospel. The insight they gain from an understanding of the Plan of Salvation and the function of this life as a period of trial and preparation makes it much easier for them to develop self-discipline in diet, dress, thought and behavior. They can view with perspective the demands on them as parents, church members, civic workers, and employees, to name but a few of the competing roles each individual must play.

East Asians reared in the intensely integrated role patterns of the traditional family or group do not easily adjust to the personal independence characteristic of modern society. The problem emerges in one form in the pattern of suicide among Asian youth, Japanese youth in particular. The role expectations of students are often overwhelming, and traumatic personal and interpersonal conflicts arise over decisions regarding marriage and a lifetime career. Faith, prayer, and other gospel principles and church practices might assist young Asians not only in weathering frequent crises but also in bearing up under the day-to-day grind. With some adjustment and direction, the traditional conditioning of Asians better equips them to adapt to Church ideals than Westerners conditioned to excessive individualism, which often runs counter to the discipline required of disciples of Christ. The Church has not only gone far to outline ideal roles for children, youth, husbands and wives, but also to establish basic guidelines regarding the interrelationship among these roles and to outside persons, influences, or institutions. Finally, an Asian convert can take a great deal of frustration if that frustration is compensated for in other ways. The key element here is a gospel which emphasizes the constructive aspect of adversity.

Greatly accelerated change in the modernization of Asian societies has created, in sociological jargon, sharp “generational discontinuities,” which are more troublesome than the “generation gap” in Western societies. In pre modern China, Japan and Korea, the assumption of social obligations smoothly flowed in conformity with the traditional criteria of age, generation, sex, family status and so forth. Now young people want economic rewards and professional positions to be determined on the basis of personal merit rather than by nepotism, family influence, and other traditional barriers to mobility. They want the mobility necessary for personal capability and effort to reap their due rewards. At the same time, the older generation is attempting to maintain the status quo, to protect their vested interests and maintain authoritarian restraints. The resulting tensions found throughout Asian societies go far to explain the underlying reasons for the growth of communism and other radical movements. Significantly, much of the revolutionary ferment of Asia is due not to Marxist ideology as such, but rather to strivings for human dignity, for opportunity, for basic human needs, for civil liberties, and often for national self-determination.

For the Asian convert, the gospel promotes a moderation which eschews violence and radicalism while bringing new dignity to the individual. In particular, it teaches the power of love, mutual respect, and effective communications in solving problems between parents and children and between leaders and followers at all levels of society. Social obligations and functions are thus carried out more smoothly, especially as the ideal of service replaces force in the effort to gain justice and effective social progress. The gospel in action in Asia certainly is not as dramatic or spectacular as Zengakuren student movements in Japan, the Red Guard youth of China, or Viet Cong activities in Vietnam, but these movements often create as many problems as they solve and are hardly worth the cost in what they do to people.

It should be added that not only are the principles of the gospel making an impact on a personal and family level, but also that the basic organization and programs of the Church are attracting considerable attention. In fact the Soka Gakkai, one of the most dynamic and effective movements in contemporary Japan, has been sufficiently impressed with L.D.S. Church organization to make a detailed study of it.

A dominant trend in Asian societies is toward a progressively more secularized society. Much of the folk religion of most Asian societies is discounted as superstition by the majority of educated Asians. While they are thus intellectually alienated from religion, both traditional and Christian, many still have an emotional urge towards some form of religious expression. As Asians study the Restored Gospel, they find that it is scientifically respectable and, moreover, that it has solutions to people’s problems, both individually and collectively. It abolishes the artificial division between the sacred and the secular, as all things become integrated in the economy of God.

This brings us to the quest for purpose and meaning of life. For most Asians this is now a continuous quest in a modern world which offers many sets of purposes but no guarantees as adequate as the former, traditional society. This is what the gospel and the Church are all about and there is nothing comparable in the experience of our Asian converts for giving meaning and purpose to one’s existence. Mormon teachings on the origin, purpose, and destiny of man answer many of the great questions currently being asked by Asians.

Only the positive side of the Church in Asia has been stressed here. There has been no attempt to analyze the very real problems which arise in the attempts of missions to transmit a traditionally American-oriented church in a foreign culture and to institutionalize the Church in Asian societies. I am well aware of the problems arising from the emphasis on quantity over quality in making converts, from attracting an overabundance of teenagers and maladjusted adults, and from a host of other problems. The intent here, however, has been to emphasize the positive role the Church may play, and in many ways is playing, on the complex, revolutionary continent of Asia. The gospel in Asia is performing the miracle of conversion and is doing so at a surprising rate. This is reflected in the recent four-fold division of the Japanese Mission, the division of the Chinese Mission, the organization of the Tokyo Stake, the opening of new missions in Southeast Asia, and in the sending to Asian countries of an increasingly larger percentage of the missionaries of the Church.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue