Articles/Essays – Volume 16, No. 3

Selling the Chevrolet: A Moral Exercise

This is the saddest story I have ever told. Not because The Chevrolet is gone, but because it probably is not.

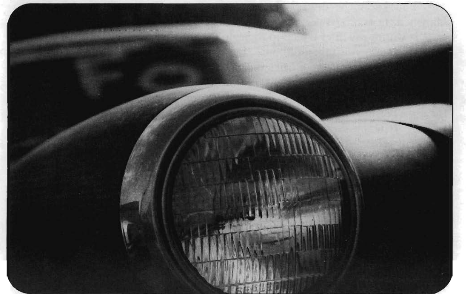

This much is known. During the Christmas season of 1973, Gene and Charlotte England traveled to Salt Lake City from Northfield, Minnesota. They made the trip in The Chevrolet—a brown stationwagon of uncertain origin.

The Chevrolet did not manage the trip very well. Little wonder, since Gene is known for keeping his automobiles well past their prime and for his hellbent-for-naugahyde driving style.

But this was no normal automobile. In “Blessing the Chevrolet,” an essay that appeared in the Autumn 1974 issue of DIALOGUE, Gene explained how on several occasions of mechanical emergency he had administered to this car, and how the car subsequently had been healed. There may be those who will question the orthodoxy of blessing an automobile; but if you allow the practice, it is difficult to imagine an automobile more in need of blessing than one driven any distance by Gene England.

As for apologizing for the practice, the pioneers blessed their oxen, which most religionists find more defensible than blessing tin lizzies, but only because modern religionists have no experience with oxen. I recently delivered a yoke of Red Durham oxen from New Hampshire to Pioneer Trail State Park in Salt Lake City. How such a fate should befall a twentieth-century writer with no agrarian pretensions is another story; but it left me prepared to bear witness that it is not possible for anything to be less deserving of blessing than oxen. Not even Chevrolets.

According to “Blessing the Chevrolet,” as the Englands crossed South Dakota on a Saturday afternoon, a long ways from Salt Lake City (as South Dakota is from anywhere), the car began to suffer. And once again, Gene healed it.

That much is known.

What I tell you now has not been known publicly. I have treasured it in my heart, waiting for an occasion to finish the story begun a decade ago.

***

During the winter of 1978, Gene and Charlotte were preparing to travel east from Provo, Utah, where Gene was now teaching. Were I to think a bit about it, I might remember where they were off to. But maybe not. All memories of that trip and the events surrounding it have been overwhelmed by what for me has become the paramount event of 1978.

Gene arrived at our house late that evening. We also were living in Provo, in Indian Hills, just a block from Bert Wilson, who had grown up with Gene in Downey, Idaho. Bert frequently would walk past our house, stop, and we’d talk. Talk about the mountains, and the sun off them in the evenings, and about Bert’s pickup which had been destroyed moving salvaged bricks from a demolition site in Orem. Gene had been building his home north of BYU’s Marriott Center parking lot—a new home built to look like an old one. Complete with a tower study behind a walnut tree, some of whose roots were severed when the foundation was poured. Hopeless case. But Gene blessed the walnut, too. We all waited for the tree to die. Everyone but Gene, who hauled bricks to build his tower behind it and watched it blossom that spring. It is the largest, healthiest tree on the block.

***

“You know, he destroyed my pickup,” Bert would tell me as the sun blanched the scrub oak on the mountains behind our homes. “It wasn’t much of a pickup to begin with, Bert.”

“What are you talking about? It was a great old pickup until it broke its back hauling twenty ton of brick out of Orem.”

Bert may have been right. But he needn’t have worried. What Gene breaks, he fixes. Wonderfully. But Bert moved to Logan before there was time for a proper healing. And Bert never mentioned the demise of his pickup with rancor. It was a sacrifice. The sort of sacrifice friends make for one another. Especially Gene’s friends.

***

Gene came over late that evening. We had just built a fire, and the light of it glistened on Gene’s teeth as he walked into the living room. (I don’t remember that detail, but I am certain it is accurate; Gene always smiles when he is about to propose something absurd.)

“We’re leaving tomorrow. How’d you like to sell our car while we’re gone?”

I had been lucky in selling an old car of ours the week before; a station wagon I had advertised for weeks, finally selling it well below low book, and happy to have it gone. Gene evidently deduced from that happy accident that I was good at selling used cars. Maybe even enjoyed it.

“I don’t know, Gene. I’d hate to screw it up some way, take less for it than you wanted, or something.”

“Don’t worry about it. Anything you get will be fine,” he said, putting his arm around my shoulder and leading me outside.

Parked in my driveway was the old stationwagon I’d seen parked for months in front of Gene’s house. I had thought it was a junker, a derelict that would have to be hauled away. But there it was, derelictingly in my drive way—mismatched tires, no hubcaps, shredded upholstery, and paint oxidized to an opaque gray that made description of its color a guess.

“How much do you want?”

“I was thinking $500.”

“Five hundred dollars! Gene, this is very much a car you would pay some one to haul away and not tell you what they did with it. When people talk about ‘scrap metal,’ this is what they’re talking about. You should have used this to haul the bricks in.”

Again he put his arm around my shoulder. “Clifton,” he said, his voice slightly sententious and low, “this isn’t just another car. This is .. . The Chevrolet.”

I suspect there are words to describe my feelings at that moment. But “awe” is inadequate. And “reverence” doesn’t work for a car with no hub caps. When I was in Rome a number of years ago, I visited a reliquary wherein was enshrined a strap of leather from Peter’s sandals. It looked old enough to be, and for just a moment I thought, “What if it is .. . ?”

That’s how I felt about The Chevrolet.

Not because I had always believed. When I had first read Gene’s essay about blessing the car, I had said to my wife, Marcia, “Too bad it wasn’t a Buick; would have given him an alliterative title.” And for days after, I felt the cynic’s need to wisecrack about “Gene England’s program of metaphysical automotive maintenance—change the oil every 2,000 miles; get a lube each 4,000; and bless as needed.” Nevertheless, for a family home evening just before leaving on a trip to California, I read the essay to my children. They liked it. More—they believed it.

We always pray before leaving on a trip. We prayed before leaving for California. But not enough a prayer to keep the car from having trouble late at night between Mesquite and Las Vegas, in that long, dark stretch of desert that worries adults. And terrifies children.

My six-year-old son Calvin sat in the front seat between Marcia and me as the car began to sputter going up one of the desert hills. Beginning as some thing of a gurgle, the missing quickly developed into a lurching indecision. I had no idea what the trouble might be. But as Marcia and I quickly discussed the alternatives if the car should break down, I felt Calvin’s hand on my thigh.

“Are we gonna be okay?” he asked.

“Sure,” I said, trying to concentrate on the rhythm of the engine.

“But what happens if it stops?”

“Everything’s fine.”

“But it’s dark. I can’t see any lights out there. What if it stops?”

Calvin was afraid. And as his fear distracted me from the car, I also looked into the night. He was right. It was really dark out there. And no cars coming.

I had no idea what we would do if the car broke down.

“Daddy. You remember that story you read us, about the man who prayed for his car? Remember that?”

I remembered.

“Maybe we should say a prayer.”

I wasn’t going to pray! I’d had too much fun over Gene’s essay. I might break down and be devoured by the dark monsters that live in the desert be tween Mesquite and Las Vegas, but I would not be a hypocrite. I would not bless the Ford!

“Daddy’s driving and can’t close his eyes, so maybe you’d better pray.”

And he did. I remember Calvin’s prayer, exactly. “Heavenly Father, please bless the car so it won’t break down and get us stuck in the dark.”

As he prayed, the car staggered up a long incline, between frequent cut aways of the hill. The engine seemed to be missing more than running. Missing to the very moment of Calvin’s “. . . in the name of Jesus Christ, Amen.”

It did not miss after that. It ran smoothly to California. It ran smoothly till the day I sold it, a week before Gene approached me about The Chevrolet.

***

“You’re selling The Chevrolet?”

“Yes. For $500. See you when we get back.” And he was gone, like one of the Three Nephites, leaving me The Chevrolet. To sell.

I parked it on the street. Put a sign in the window. “$500 or best offer.” Any offer. However unique its history, however often blessed its past, however much I had come to believe in the blessing of oxen and children and auto mobiles, this was a car that had seen better days, a long time ago.

I knew what was going to happen. The car wouldn’t sell, at any price. Gene would get back from his trip and say something like, “You’re doing a good job, Clifton. You just go ahead and keep doing what you’re doing.” The car would stay in front of my house until it collapsed into its own rust.

I was very discouraged. But it was The Chevrolet. And Gene was Gene. What was there for me to do?

***

I needed to do very little.

Three days after Gene left, I was again sitting in front of the fire, working on an essay about the sacrifices friendship can demand. About bricks and pickups; about station wagons whose blessings are used up.

I had just gotten up to stoke the fire when I heard the crash. Not quite a crash. More a crunch. Not enough of a noise to go see about.

In a moment, there was a knock at my door. “I’m really sorry,” the frightened young man apologized, “but I ran into your car. The stationwagon. I just didn’t see it. Seemed to come out of nowhere.”

I put my arm around his shoulder, as I imagined Gene might do. “Don’t worry, son. Believe me when I tell you this isn’t your fault. It’s the car. Selling itself. Nothing you could have done about it.”

The boy pulled away from me, uncertain whether he might not be in more trouble than he had imagined.

We called his father to find out his insurance company, and the next day I drove the further-mangled Chevrolet down for an appraisal. The settlement came to $332. A little less than $200 short. But I wasn’t worried. No faith is stronger than the faith of the faithless converted.

***

Two days later a seminary teacher offered me $200 for The Chevrolet. “For parts,” he said.

I didn’t tell him about the car’s history. You can never be certain about the religion of a seminary teacher, and I didn’t want to screw up the deal The Chevrolet had arranged. I took the $200 and watched The Chevrolet move off down the street.

However remarkable its past, I was glad to have it gone. Not because I hadn’t grown fond of the car or because I had the least suspicion of its being a Mormon monkey’s paw, but because I would have the money for Gene.

When I gave it to him, he smiled, not the least amazed. Nor was I.

***

A few months later, I saw the seminary teacher to whom I had sold the car. He was driving along Main in downtown Provo.

He was driving The Chevrolet.

He was smiling.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue