Articles/Essays – Volume 01, No. 1

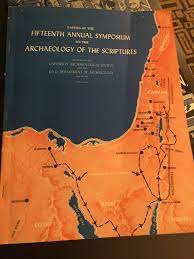

Some Voices from the Dust | Ross T. Christensen, ed., Papers of the Fifteenth Annual Symposium on the Archaeology of the Scriptures

Any volume with “fifteenth annual” in its title requires placement in historical and sociological context before it can be evaluated properly. Sponsor of this symposium is the 800-member University Archaeological Society. (The name was changed in 1965 to Society for Early Historical Archaeology.) The society began in 1949, in affiliation with the Department of Archaeology at Brigham Young University, which had been organized two years earlier. The personalities and institutions related to these beginnings, or deriving from them, are responsible for most serious Mormon thought on the relation between archaeology and the scriptures.

Joseph Smith himself had views on this subject which were published at length, particularly in The Times and Seasons. Early in the development of Mormon tradition his views, considerably simplified, became so firmly established that they were hardly challenged for a century. Mormons usually considered that all Indians were Lamanites and that the “antiquities” of the New World were products of the Nephites, Lamanites, and Jaredites. As for the biblical area, that was of secondary concern; the little supplementary factual information utilized was simply borrowed from “Gentile” scholars.

By the 1930’s academic anthropological scholarship had developed an orthodox position about the peopling of the New World and the development of cultures here. Sharp contrasts between this scholarly view and the received beliefs in the Church led to difficulty for many an L.D.S. student in higher education. Two students at Berkeley, M. Wells Jakeman and Thomas Ferguson (and to some extent Milton Hunter), tried to work out a viable position for themselves between the conflicting views. As a result they emphasized the documentary traditions and certain archaeological and geographical features of Mexico and Central America, placed in alignment with the Book of Mormon account.

When a position at BYU was arranged for him in 1946, Jake man, with a Ph.D. in history supplemented by some anthropology, brought to the new department and the affiliated society a position characterized by high respect for classical studies, preference for documentary sources, antipathy toward anthropology (the main disciplinary vehicle for the relevant archaeological work both then and now) as it was then construed, and zeal to enlighten those Mormons who held uncritically the traditional views about the scriptures and their context. Of the small number of Latter-day Saints at present qualified to speak seriously to this subject, nearly all have been under Jakeman’s tutelage and have at some time shared many of these same penchants.

While the UAS was aborning at the Y, Ferguson produced a sort of landmark book, with Hunter’s collaboration, and then went on to organize the New World Archaeological Foundation. His rationale, unlike that of Jakeman, was that work in archaeology necessary to clarify the place of the Book of Mormon account would have to be done in collaboration with non-Mormon experts, not in isolation from them. Thirteen years of changes in the NWAF have seen it become converted into an element in the BYU structure and gain a respected position as a research agency in Mesoamerican archaeology, but in concept and operation the Foundation and the Department remain far apart.

Various individuals unconnected with these institutionalized activities have also wrestled with the archaeological problem. Few of the writings they have produced are of genuine consequence in archaeological terms. Some are clearly on the oddball fringe; others have credible qualifications. Two of the most prolific are Professor Hugh Nibley and Milton R. Hunter; however, they are not qualified to handle the archaeological materials their works often involve. And as for the study of archaeology in relation to the Old World scriptures, not a single Mormon with professional standing has adequate expertise to address that subject properly.

The symposium reported in the publication under review displays the organizational variety, and even rivalry, just sketched. The inclusion of five student papers along with those of Ross T. Christensen and M. Wells Jakeman, while nothing appears from Lowe, Warren, Matheny, Green, Lee, Carmack, Spencer, Nibley, Meservy, and others, suggests the limits implicit in the membership list. Unevenness of quality inevitably marks a volume with a heavy proportion of amateur contributors. This raises the question, which the UAS has never faced squarely, of its central objectives. Is it to assist in the development of new knowledge? Is it to provide a vehicle through which “the findings” of archaeology are reported (and interpreted) to L.D.S. lay people, as Christensen (pp. iii and iv) implies? Is it an enthusiasm-generating device primarily, busily engaged in fulfilling Parkinson’s laws? No clearcut answer is apparent from this volume.

Dealing with individual papers is difficult due to the limitation on review space, but readers of this journal without the symposium volume at hand need to have the contents clarified. A capsule guide to each paper will, therefore, be given.

***

Howard S. McDonald and Francis W. Kirkham reminisce briefly about their association with the early activity of the Department of Archaeology and the UAS. A. Richard Durham makes some observations on Joseph Smith’s knowledge of Egyptian, but the slim factual substance of his key point, which could be of more interest if properly developed, tends to get lost in a wordiness which too consciously apes the unique style of Hugh Nibley. Curt A. See mann summarizes some of the secondary and tertiary sources concerning the Israelite conquest of Canaan, as they are somewhat in formed by archaeological work. While serving a certain journalistic function adequately, this paper has nothing to say that has not been said better elsewhere. Louis J. Nackos contributes a similar type of summary concerning the situation in the land of Judah just before the Babylonian conquest, but the sources he utilizes are even slimmer than Seemann’s. For example, no note is even made that Torczyner’s translation of the Lachish letters is questionable. Einar C. Erickson’s paper recites more or less the events connected with the reign and fall of Zedekiah at the beginning of the sixth century B.C. The sources are little more than the Bible, the Book of Mormon, and standard reference works. Some of the speculations are wild. V. Garth Norman attempts to relate some scriptural and archaeological information to his interpretation that the seven golden candlesticks mentioned in Rev. 1:12 are ultimately “identical” in “symbolic concept” to the Tree of Life referred to in the Book of Mormon. Unfortunately I do not find the proposed connection either as convincing or as significant as does the author. Naomi Woodbury’s little piece would better have been developed much further before being made public at all since it is virtually lacking in substance. Carl Hugh Jones has an idea on which solid research might well be done, concerning difficulties which the transfer of crop plants might encounter when borne by Jaredite and Nephite colonists from the Old World to the New. The data he musters are, however, insufficient to draw any reliable conclusions ; all he has really done is partially to delineate the question.

Tim M. Tucker claims to have made a “detailed comparison” of Mesoamerican temple-towers and the ziggurat structures of Mesopotamia. The same observations, in about the same detail, have been made a number of times before at UAS meetings or in classes. Problems in the comparison are glossed over. (For example, lumping the entire period from 2500-100 B.C. as a single “Pre classic Era” leaves the implication that the “sudden” appearance [actually an evolution covering centuries] of temple-towers in Middle America was somehow near in time to the Mesopotamian structures.)

In a bit of incidental history, M. Harvey Taylor sketches the life of Paul Henning, the earliest professional archaeologist who was a Mormon. Also historical is Ricks’s documentation of a look by a group of Mormon investigators at a spurious Hebrew inscription. Read H. Putnam’s paper was given at a symposium a decade earlier and appears here in slightly different form. It is noteworthy as one of the few contributions here of new knowledge. Ironically the man who produced it makes no pretension of academic scholarship, but he has shown in this article the possibilities open to a lay man who is determined to become well informed on a narrow topic. M. Wells Jakeman briefly presents some of the materials on “A Possible Remnant of the Nephites in Ancient Yucatan” which derive ultimately from his dissertation. Some of the phrasing and documentation differ from what he has either written or stated orally before now, but there is really nothing new here for those who know his earlier work.

After having been absent from this literature for a few years I am struck by several recurrent features displayed in the papers. Despite the title of the symposium there is little archaeology here anywhere. There are only six references in the entire volume to primary archaeological accounts! What has really been done is to stew together the scriptures and some secondary historical materials, adding a bit of archaeological salt and pepper. Surely the recent change in the name of the society is proper in the light of these contents.

***

At least six of the participants display that favorite methodology of Mormon students of the scriptures, uncontrolled comparison. Lexical pairings are the simplest to make (e.g., p. 45, where the names Mulek, Melek, Amulek, Amaleki, Amalickiah, and even America are gratuitously linked to each other). But then there is a long tradition of this sort of thing among us Mormons, to which I made my own sizable contribution in more naive days. Comparison of symbols — always a tricky business — is another standard procedure. Jakeman’s paper carries trait-list comparison to its logical conclusion (p. 117) in a manner which shows unambiguously the influence of A X. Kroeber and the “Culture Element Survey” at Berkeley in the 1930’s. Obviously comparison remains a key methodological device in the conduct of research in history and the sciences, but the uncontrolled use of trait comparison leads to absurd conclusions. Particularly, it leads to overambitious interpretations of shared meaning and historical relationship, as in Jakeman’s previous pseudo-identifications of “Lehi” (and other characters from the Book of Mormon) on an Izapan monument.

One other pervading characteristic of these papers is their lack of currency. Christensen recommends the UAS (p. iv) as a means for “keeping up to date with the fast-moving developments now taking place in the archaeology” of scriptural lands. Yet these presentations, with the possible exception of Durham’s, are exclusively concerned with questions and answers which have changed in no significant way in at least a decade.

Where is Mormon thought on archaeology going? After this rather discouraging display of the lack of progress on the topic, is anything happening that is more dynamic and promising? Yes, some things. Increasingly young Latter-day Saints are feeling that it is desirable and respectable to become professionally prepared as archaeologists, at least for the New World, which means they must qualify as anthropologists. In a few years a sizable cadre will be scattered throughout the country. One reason those already established have not been more influential to this point is the resistance to innovation on their part which authorities and members generally have manifested. As long as Mormons generally are willing to be fooled by (and pay for) the uninformed, uncritical drivel about archaeology and the scriptures which predominates, the few L.D.S. experts are reluctant even to be identified with the topic. To paraphrase Adlai Stevenson, “Your archaeologists serve you right.” But this does not mean that the handful who are qualified have done all they could to phrase and communicate what they know. Cyrus Gordon, speaking of ancient Near Eastern studies, has said that they “must languish unless they are actively related to something vital in modern occidental culture.” Is “proving” the Book of Mormon sufficient to provide the “drive and stamina to master a whole complex of difficult sources which serious scholarship will require?” Additional motivation may be needed.

Encouragement about future developments can also be drawn from the evident fact that the younger scholars are successfully relating themselves to the professional scientific world around them, rather than isolating themselves in an artificial “scriptural archaeology” cocoon. Precisely how the roles of Mormon and professional scientist are to be balanced remains to be worked out, but at least today’s young scholar is clear that the one should not, can not, replace the other.

Unfortunately, the Fifteenth Annual Symposium volume displays few encouraging signs. It is relatively harmless, mildly diverting in spots, and no doubt gives comfort to some of its audience, but it is not important.

Papers of the Fifteenth Annual Symposium on the Archaeology of the Scriptures. Edited by Ross T. Christensen. Provo: Extension Publications of Brigham Young University, 1964. vii+120 pp. $1.00.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue