Articles/Essays – Volume 32, No. 4

Stealing the Reaper’s Grim: The Challenge of Dying Well

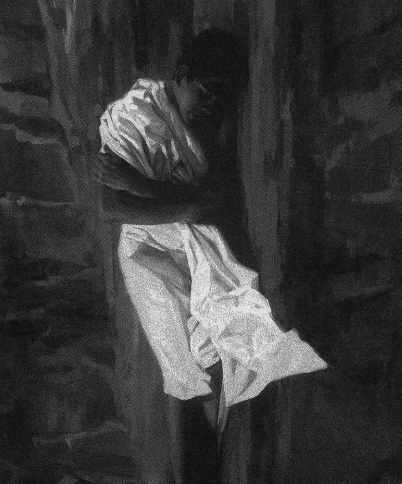

That your dying be no blasphemy against man and earth,

my friends, that I ask of the honey of your soul.

In your dying, your spirit and virtue should still glow

like a sunset around the earth.

Friedrich Nietzsche

I first encountered death at age three when my infant brother, after only one day of life, succumbed to respiratory failure. I have few memories of the viewing, but do recall the delicate blue veins on the side of his infant scalp. There was great sorrow in the chapel. But, as the years passed, his death became an abstraction. Now, over three decades later, after witnessing a fair amount of human suffering and death, both through personal experiences and my professional role, the process of dying is no longer an abstraction to me. I have, in fact, become a reluctant authority.

As a 35-year-old physician, I approach the new millennium with the knowledge that I will not see much of it. I first stared at my terminal ill ness on November 12, 1998 when I stepped out of an MRI scanner in El Paso, Texas, and was the first to see my tumor, the first to realize my life had changed forever. Clearly, the malignant glioma in my brain had existed sometime before that day, but the process of “dying,” at least to me, began with the realization that the beast was there.

The world I knew one year ago is closed to me now. I was then a board-certified radiologist, performing angiograms and other procedures, interpreting MRI images of the brain and spine, and moving into a five-bedroom home with my wife and three young children. Today, a new reality frames my world: I am an unemployed, disabled veteran. And last week I found myself at Brown Monument and Vault in Logan, Utah, looking at different designs for a headstone to put on my grave. I like the Georgia granite best. And no elk. I do not want elk or too many flowers on the marker. Just name, birth and death dates. Nothing ostentatious.

As of this writing, I am some distance off from my last breath. Of course everyone on the planet is journeying to that point from the day he or she is born. We are fellow travelers to the graveyard. I simply know that I am much closer than the vast majority of people around me. And I have not yet given up on life, though the odds of my surviving this are monumentally small, not unlike the chance of winning a multi-state lottery. Each day has become more important as I try to savor the time I have left. Moreover, each day I face the challenge of facing death.

Much of the impetus to write these words comes from the excellent 1997 book, On Dying Well, by Ira Byock, past president of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and a prominent advocate of educating people and physicians about effective hospice care for the dying.

From his years as a hospice physician, Dr. Byock has learned that with modern and effective pain management, with trained physicians who are not afraid aggressively to treat the dying, and, most importantly, with supportive family, friends and health workers, dying need not be an agonizing nor a lonely event. “Physical suffering can always be alleviated,”[1] he asserts. The book was comforting.

Byock also writes about personal and spiritual growth that can occur in the patient, his family and friends. At first, I recoiled at the idea that merely taking a last breath in relative peace was not sufficient to have a good death. I thought that was already asking a lot. But I learned I had to do much more. I’m not sure it is possible to issue a blueprint for “dying well.” Aside from suicide or euthanasia, none of us can choose how we die. If a “good death” implies a peaceful transition at the age of 90 in the middle of the night and incident to old age, then I will fail miserably, both because of my relative youth and the modus of my exit. Others die quickly, through trauma, homicide, an acute myocardial infarction, or stroke which prevent them from “preparing.”

I remember well the 45-year-old woman I followed as a medical student who had end-stage esophageal cancer. She was beautiful and seemed to accept her fate with grace, and she was surrounded by friends and family. Yet, late one evening in her hospital room, her cancer eroded into a large artery, forcing her to start coughing up blood. She bled to death, alone, that evening. It is tempting for me to label her death as perhaps the most blatant case of “dying poorly” I know of, at least in its final stage. Nevertheless, through her unusual acceptance of her disease and approaching death, she herself remains free of any responsibility. This is simply the fate of some despite all their best efforts to plan otherwise. For many, however, especially those like me with an aggressive, inoperable cancer, there are things we can do to increase the likelihood of dying well.

What follows is infused both with my medical bias and with the experience I’ve had within my Mormon culture. I wish I could document all of my dying: the final days and hours, the pain management, the level of anxiety, the agony of separation from those I love, whatever degree of acceptance I will have achieved. I would even attempt a vivid description of the notorious “tunnel of light/’should it be waiting for me. But obviously much that I would willingly share will go unsaid.

My Story

Even the beginnings of my story will doubtless be incomplete. There was paresthesias or a tingling in the first three fingers of my left hand. My wife Leesa and I and our three children had moved to El Paso just a few months prior as part of an assignment to serve in the radiology department at William Beaumont Army Medical Center. I had just completed eleven years of medical training, the last two as a neuroradiology fellow at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). The symptoms I was having in my hand were very worrisome to me. I was concerned that I might either have a cervical disc herniation or, worse, multiple sclerosis. As the chief of the MRI section at the hospital, I had ready access to the MRI scanner, and, during a lull in patient needs, I put myself into the scanner. Sometimes I wish I had not.

That, as an expert in the interpretation of brain imaging studies, I should discover my own brain cancer is, by itself, an almost literary irony. But fate seemed to have packaged a bewildering array of attendant ironies: I had just passed the Army’s physical fitness test as well as my final neuroradiology boards just days before the MRI; I was already scheduled to conduct the first neuroradiology conference at William Beaumont the day after my MRI; I had given a lecture at the National Brain Tumor Foundation Annual Meeting in March 1998 in which I had spoken to brain tumor patients and their families about how we, as neuroradiologists use CT and MRI technology to help diagnose brain tumors; and in the summer 1998 issue of Dialogue, an article of mine appeared in which I praise our human flesh as co-equal with our spirit because of its marvelous origins, its central role in human suffering and disease, and the pivotal role the human brain plays in this existence despite its perilous proximity to chaos in the form of tumor, stroke, mental illness, or dementia.[2] I felt as if I had been set up.

The drive home on that November day to tell Leesa the news was extraordinarily difficult. I knew all too acutely that my disease would affect others, including our three beautiful children. When I could get Leesa alone in our bedroom, I told her about the scan and ended equivocally with, “I think I have a brain tumor.” I might as well have plunged a knife into her chest. We cried for some time, but talked openly that evening about the implications. I read a couple of extra bedtime stories to Katie, Andrew, and Miranda, trying to fight back hard emotions with each page. That evening, for the first time, I had the sickening feeling that I had suddenly become less a member of the family.

Calling my father was particularly difficult. He had been struggling with the full-time care of my increasingly confused and physically limited mother, who had Parkinson’s disease and associated Alzheimer’s type dementia. The news I relayed gave his already melancholy outlook an even darker cast. I called a few others: my in-laws, Allan and Kaye; my brother John; and a couple of friends. News travels fast when you are relatively young and dying. Almost immediately I started receiving calls from people I had not heard from in years. It was a revelation to me how such news affects people. It jars them. Those of us with a terminal illness are an oddity to the living: we have entertainment value. Still, it was genuine concern I heard through the receiver. Offers to help in any way rolled in. And, though I felt it was premature and embarrassing, I was humbled when the El Paso 13th Ward held a fast for me just a few days later.

Shock and disembodied numbness followed me around those first days. Almost immediately I had recognized that I was going to die, that the images before me on the film represented an inoperable “glioma,” one of the most common and most deadly brain tumors in adults. As my hospital’s expert in neuroradiology, I took it upon myself to dictate-with some morbid fascination-the report of my own MRI. I concluded the re port stating it was most likely a glioma, mentioning a few benign things the lesion could represent, but conceding that “this would be wishful thinking on my part.” It would be one of my last dictations as a radiologist.

I did not look at those images of my brain in a vacuum. I sent copies of my films to my former neuroradiology attending physicians at UCSF and to radiologists at Walter Reed Army Medical Center. For a few days, I held out the unlikely hope that this was a rare presentation of multiple sclerosis, a terrible disease, but one with which I could live. But other doctors only confirmed my own initial impression: The prognosis was not a good one.

I flew to Washington, D.C., and Walter Reed Hospital for evaluation and a decision about what should come next, and stayed with my close friend Ted Swallow and his wife Ruth. Ted, a neuroradiologist at Walter Reed, and I are nearly identical twins with unusually commensurate histories from sharing a locker in high school to attending Utah State as undergraduates and the University of Chicago for medical school. Somehow the Army assigned us both to Walter Reed for radiology residencies, and there we served as chief residents together. Finally, we both chose neuroradiology as a sub-specialty. It has, in fact, been our mutual respect and unusual convergence of interests that have kept us on parallel paths. Nonetheless, and despite our long history together, I have advised him to forego the brain tumor.

It was no surprise when the tests at Walter Reed did not change the diagnosis. Ted said that my MRI looked “ominous.” This was not news but, coming from him, was hard to hear. It was not easy on Ted or Ruth either. It scared them. They made adjustments in their life insurance policies. It was, in fact, just this kind of response from fellow physicians which finally confirmed for me in real terms that I had become fodder for worms: The chief of radiology back at William Beaumont gave me the classic 1969 book On Death and Dying by Elizabeth Kubler-Ross;[3] the physician in charge of radiology assignments for the Army told me he would be happy to send Leesa a packet of information on death benefits for surviving spouses; and the chief of radiation oncology at UCSF, where I decided I would receive medical therapy, told me, “Paul, you’re sitting on a time-bomb.”

This all happened in the first week after my MRI. The unusual medical insight I had from the outset was, in my mind, a blessing. I could approach the disease realistically. I already knew the implications and the risks of a brain biopsy, that my tumor’s location in the right Rolandic region put both sensation and motor control of my left hand, arm, and face into jeopardy, and that I would have to undergo the unpleasant side effects of radiation therapy and probable chemotherapy. I had participated in many neuro-oncology conferences in which patients with gliomas like mine are discussed and where radiation oncologists and neurosurgeons and neuro-oncologists debate the next option for patients with dismal prognoses. Oncology is at present an inexact science, but these conferences do help to ensure that patients get the care that will most likely prolong quality life.

I could play at being objective. I certainly had the tools. Still, no one, not even a doctor, is taught how to die. And despite my knowledge, I was very, very scared. Immediately I began struggling to balance measured hope against the likely reality that I would never reach my 40th birthday. I had known from day one that I would fight this thing, give it no advantage in destroying or in shortening my life. I wanted the most effective, most current treatments; I wanted the old college try. This I decided to do as much for myself as for those around me. My wailing and gnashing of teeth I did at home and alone. And during those first nights, I was forced to address what role, if any, God might be playing in this disaster. I adopted the premise that this was none of his doing.

And so, my medical therapy began. Every dying person has a unique medical history and experience with the struggle to find a cure. To briefly review mine, I underwent a brain biopsy in January 1999 at UCSF, which revealed I had an anaplastic astrocytoma, a malignant glioma or, in other words, brain cancer. I then received six weeks of radiation therapy, during which time I was plagued by seizures. Unfortunately and quite surprisingly, my tumor responded poorly to the radiation. As a consequence, I had to undergo a frightening awake craniotomy to “de bulk” the tumor and to place 1125 radioactive seeds into the tumor bed in an attempt to control the growth of the tumor left behind. I suffered a stroke during the surgery, which resulted in significant weakness to my left side and set me up for blood clots in my leg and, subsequently, my lungs. I spent three weeks in a rehabilitation hospital relearning to walk. I completed four cycles of chemotherapy with a new chemotherapy drug, and though there was initial evidence the chemotherapy was working, the most recent MRI shows interval growth of the tumor. I am having increased headaches which will require that I go on cortico steroids to reduce the swelling around the tumor. And I will try at least one more chemotherapy regimen.

A rough framework of how much time I have left suggests only this: far less than I had anticipated in January. But I will try to fight this until I feel it is no longer in my best interest to do so. Meanwhile, I understand the importance of continuing to live a day at a time. It is my belief that the simple yet important things of life do not necessarily perish with the diagnosis of a terminal illness. There will, I hope, still be opportunities to go on trips, play with the kids, do the dishes, pay the bills, listen to music, help with the homework, attend a couple of football games, go to movies, do a little bit of writing, share happy moments with my wife and family, renew friendships with some people and reach closure with others, search for spiritual meaning in and acceptance of the life I have lived, and search for healing even in the absence of cure.

A Philosophy of the Reaper

I knew I was mortal for the first time when I broke my clavicle at football practice in 9th grade. It forced a paradigm shift in my nascent sense of justice in the universe. I’m not sure I ever recovered. No matter how sophisticated or wise we may claim to be, this discovery of our own mortality is invariably painful. Death, when it occurs beside us, brings a rude awakening. Our society does not help as it implies that with more vigilance, a more intense morning workout, a judicious search for polyps or lumps and elaborate medical intervention, death can be avoided or in definitely postponed. This we assume even in the face of thousands crushed in an earthquake or the tortured dying of a neighbor from cancer. Somehow those deaths do not apply to us.

Hence, when death or the process of dying hits home, there is outrage. Much of this reaction comes because death, for the most part in the western world, is hidden. We have been sheltered from death. Dr. Lewis Thomas, the great medical essayist, describes our failure to appreciate death’s ubiquity:

It is a natural marvel. All the life of the earth dies, all the time, in the same volume as the new life that dazzles us each morning, each spring. All we see of this is the old stump, the fly struggling on the porch floor of the summer house in October, the fragment on the highway .. . I suppose it is just as well. If the earth were otherwise and all the dying were done in the open, with the dead there to be looked at, we would never have it out of our minds. We can forget about it much of the time. . . . But it does make the process of dying seem more exceptional than it really is, and harder to engage in at the times when we must engage.[4]

When confronted with our own death, our response and ability to cope is determined by our matrix of experiences. Those entirely sheltered from death and human suffering will undoubtedly undergo great shock. Without some prior personal experience, the dying must grapple with difficult questions at a time when, emotionally, they are least capable of doing so. It is hard to know how to teach death when people don’t want to see it. As a physician, I have seen death on a few occasions, but the death which burns still in my memory is the first one I experienced as I attended an elderly man in a nursing home the year before I started medical school. I can still hear his labored breathing, see his wife and daughter at his side. It was my bathing his dead body and helping the mortician to place it into a red velvet bag that made tangible and moving for me the experience of death.

Some time later I spent a night assisting a man, a friend of my par ents, who was dying. I recorded the event in my journal on April 26th, 1987:

This week I turned a year older. Last Monday night, my birthday, I spent the entire night at Bryant Smith’s home in River Heights. Bryant and Linda, his wife, are good friends of my parents, he being a member of the faculty at Utah State University . . . Bryant is also dying of brain cancer.

Mom, knowing that I had some experience from working at Sunshine Terrace, offered my services to Linda, who needs help standing, moving, and toileting her husband. Bryant has undergone chemotherapy and radiation treatments, but the cancer is not responding. He suffered a massive stroke several months ago, which surprised everyone (considering he is only in his early forties). The stroke was apparently caused by his growing brain tumor, which was detected thereafter.

He has lost most of his motor control on his right side and is unable to speak. . . . He has become incontinent and requires help moving to his portable toilet. . . . Friends and relatives have come in to help as much as they can.

The house was beautiful both inside and out. Linda was there to greet me and introduce me to Bryant in the upstairs bedroom. His face showed little signs of the malignant tumor inside his head. But his eyes revealed a resignation of sorts. He was fairly alert and seemed to enjoy watching TV, but he said very little the whole night, except yes and no responses to my questions. . . .

I helped him to the toilet twice during the night, but I slept only an hour at the most. Every time he would stir in bed, my heart would jump. He is still independent and has fallen in his attempts to move. .. . I would hear him move, and I supposed the worst each time. His sleep was not restful.

His internist has given him only a couple months to live. . . . His steady loss of function must surely be proof enough to him of the inevitable end.

I don’t know where Linda has derived the strength to continue. . . . She has a great sense of humor. . . . Leesa had a class at Utah State with her this year and she enjoyed Linda’s friendship.

I felt guilt that night. I felt an implied indignation coming from Bryant as I helped him to the toilet, as if I were being discourteous in flaunting my health in front of him as he withered away. Helping the aged at Sunshine Terrace, I am free of any such condemnation: They are old and are expected to be falling apart, losing their minds. The middle-aged Bryant Smith, on the other hand, should have years in front of him. Even though I gladly offered my assistance, my mere presence in his home seemed, for some reason, presumptuous on my part: as if I were saying to him that I had any more right to be alive.[5]

Those are haunting words for me. But Bryant gave me a gift. By al lowing me to serve him that one short evening, he initiated my own preparation for dying of brain cancer in my 30s. We best prepare for our own death by observation of, and, more importantly, participation in the dying of others.

This education becomes more acute when we participate in the death of a loved one, a family member. My mother, whom we placed into a nursing home the week before Christmas 1998, had fallen in the nursing home, broken her hip, and subsequently developed an infection. She passed away on February 16, 1999, three months after I discovered my brain tumor and the same week I learned that my tumor was growing despite radiation therapy. It was a rough week. The Alzheimer’s-type dementia which is seen in up to 15% of older patients with Parkinson’s disease robbed my mother of much of her connection with the world at her death. It was difficult to watch her slowly fade over three years. But none of us gets to choose the illness that will strike us down.

Despite all that, I believe my mother died well. Her method of preparing was years of unwavering commitment to her Mormon faith; a belief in resurrection and renewal; an amazing ability to cultivate friendship with others; and participation in the lives of family and friends who rallied around her during her last months, weeks, and days. She had a personal conception of death, which, for those around her, made her passing more a celebration, less a shock. It was emotionally hard for me to sit by her side over several days, to hold her hand, occasionally to kiss her moist brow, and to watch her breathing become more labored, but it was a sacred privilege. I looked to her for an example of how to face what lies ahead of me.

And it has been three generations of dying that I have now witnessed. My maternal grandmother died in the late 1970s of pancreatic cancer after languishing in a nursing home. I have vague memories of visiting her there. Those memories would have remained sealed had I not recently discovered in my father’s home, tucked into an old set of scriptures, the now yellowed and slightly ripped talk he gave at her funeral. He praised my grandmother for her “quality of dying”:

What meaning can be derived or purpose served from being confined to a bed, half-paralyzed, for months on end, with full knowledge that death is the only escape? This is the question that always emerges when prolonged human suffering is confronted in any form. Bitterness, rancor, even verbal cruelty are not uncommon attributes in those who must carry the heavier burdens of mortality. They lash out at the . . . injustice of life, and in that lashing, they often strike those they love most. Probably the ultimate tragedy for some who are called to suffer is that they only have themselves for focus. Not Blanche Anderson.[6]

I have come to believe that whether we have had an experience with dying or not, we will finally benefit greatly if, at some level, we have already established our own “philosophy of the reaper.” My personal journal has been a crucible through which I have struggled with the idea of human suffering and death. I think these late night tappings on the computer keyboard have helped prepare me for the loss of health, the injustice of dying young, and given me a better understanding of what lies ahead. In October 1995,1 wrote in my journal that I had been lucky to have good health:

I use the term “lucky” instead of “blessed” because I seriously question how much God gets involved in assigning the cancers or curing the gout. I think of health less as a gift or blessing we receive and more as a personal treasure that we stumble upon. As Job learned, that treasure can be lost in an instant. It is, therefore, an elusive treasure. We can attempt to lock it away in a vault, but some day, for all of us, the treasure is no longer there.[7]

Elizabeth Kubler-Ross describes what have now become the classic “stages of grief,” which the dying person may encounter as he or she processes the reality of loss: denial (the patient refuses to believe he or she is confronted by a terminal illness); anger (raises the universal question: “why me?”); bargaining (attempts magically to postpone death by making promises to God); depression (succumbs to the sense of great loss and to the fear of death, pain, dependency, and expensive, uncomfortable medical treatments); acceptance (the patient ultimately finds some inner peace and is able finally to place his or her death in a larger context).[8]

Many have been critical of these stages of grief for being too formulaic. And indeed, some patients may skip stages, return again and again to a particular stage, or experience two or more stages at the same time. In my own case, I have found myself going backwards. Due, I think, to my medical background, I began with an unusual acceptance of the in evitability of my death. Since then, I have experienced equal and concur rent waves of anger and depression. I do not think I have ever bargained with God, trying to make a disingenuous, shady backroom deal: “I will stop being skeptical in exchange for a miraculous healing.” Even now, I know better. But I have had flashes of denial during this nightmare, especially when lost in the moment, playing with my children.

I have tried to divine the etiology of my cancer, a particularly futile and frustrating undertaking. As a physician, I know there is no one clear and well-documented cause of malignant brain tumors, although many have been proposed: genes, ionizing radiation, exposure to toxic chemicals or pesticides, diet, prior viral illnesses, head trauma, artificial sweeteners, electromagnetic fields, and many more.[9] Still, I find myself asking, what did I do wrong to forfeit half a lifetime? Maybe I should have chosen the spinach instead of the corndog in the lunch line as a third grader. Maybe I swam too often in the slightly cloudy Chico creek as a boy. Perhaps I am simply defective. This self-blaming is perhaps the worst form of anger.

Depression has also hit hard at times. For me it is the knowledge of how much I’ve lost. It is my altered state, my suddenly “devalued” status in the pragmatic eyes of society that eats at myself esteem. In fact, my greatest concern during that first week following my MRI was not that I was going to die, but that I would never be a radiologist again. For some time after my diagnosis, I held out the dwindling hope that after my initial treatments I would return, if only for a short time, to work.

Medical Therapy: Buyer Beware

During all this adjustment to the news and the reality that one is dying, there is an immediate and continuous necessity to seek reliable, accurate information-even for a physician. The process of death is a spiritual journey for all people, but it is also defined by and remains within the domain of medicine. The words “your illness is terminal,” or “you have six months to live” should be a sounding cry to fight. The patient needs access to vital data relating to treatment options, side effects, and prognosis. This may come from the physician, but there are also other sources: second opinions from other physicians, fellow patients who have undergone prescribed treatments, national organizations and sup port groups, or perhaps independent research.

When traditional therapies do not work, the patient should consider new protocol medications, procedures, and “peer-reviewed” therapies that are being tested. Patients who chose to do so become brave pioneers who may prove the efficacy of new treatments. This is the basis for advancement in medicine. I hope one day this courage to try new therapies will lead to a more effective treatment for deadly malignant brain tumors. I applaud those who seek second opinions, conduct their own research, set up “war rooms” in their homes, and refuse to give up hope.

But there is also a cautionary tale to tell. Not long ago in San Fran cisco, I met two auto mechanics in the waiting room of the radiation oncology department at UCSF. Tom was the younger and he was leading a frail Randy, who spoke little and could only walk with a walker. We ex changed histories, and I learned that Randy had widely metastatic small cell lung cancer to include brain involvement (a sure death sentence). But Tom produced a piece of paper containing “research” he had gleaned from the internet showing that with a dose of 5-10 cloves of garlic a day plus assorted herbs that could be ordered directly on-line, “any cancer could be cured in ten days or less.” Tom was excited about this. Tom said he and Randy had decided to try this “radiation stuff” suggested by Randy’s doctor, but they were both looking forward to getting back to work soon. “After all,” Tom said, “this can’t be nearly so difficult as that ’92 Nissan we fixed with the nasty intake valve . . . isn’t that right Randy?” Randy nodded his head in agreement.

I paused for a moment, smiled, and wished them luck. The internet can be an excellent source of medical information (70% of Americans will search for medical information on the internet before they visit a doctor[10]), but the internet is also a breeding ground for quacks. The Federal Trade Commission recently warned that at least 800 websites make unsubstantiated claims to cure, treat, or prevent cancer, heart disease, AIDS, diabetes, arthritis, and multiple sclerosis.[11] There has, in recent years, been an explosion of “alternative” medical therapies attractive to patients whose chronic illnesses do not yield to treatment by mainstream medicine. The list is endless: herbalism, homeopathy, chiropractic, mas sage therapy, naturopathy, folk medicines, magnet therapy, aroma therapy, colonic therapy, Ayurvedic medicine, chelation therapy, Qigong, Reiki or “touch” healing, yoga, and on and on.[12] It is true that insurance agencies are beginning to cover some of these treatments, and government agencies have established national offices to begin, albeit inadequately, to investigate their claims,[13] but many, perhaps most, of these therapies are rooted in fantasy, Shamanism, and market economics. Web sites tout treatment with magical catch phrases such as “painless,” “all natural,” “non-toxic,” “all-herbal,” “rejuvenating,” “miraculous cure,” “secret ingredient.” The cruel result is that many terminally ill patients, turning to alternative medicine out of desperation, spend thousands of dollars on misplaced hope.

There are some simple techniques such as music therapy, massage therapy, and the meditation of yoga which have been shown to promote relaxation and an “inner healing” in terminally ill patients. I personally think that dixieland jazz is the ultimate alternative medicine, especially after a recent trip on which Leesa and I stayed in the French Quarter, the “Vieux Carre,” of New Orleans. I found true healing in the Palm Court Jazz Cafe. That, of course, is a testimonial, a shared personal experience, but the terminally ill must realize, as they search for medical therapy and information, that testimonials are for revivals, not a basis on which to make important and costly medical decisions.

Mormons, unfortunately, have a history of being attracted to the medical fringe. I have had several, well-intentioned LDS people, who, knowing my medical background, sheepishly approached me with suggestions of special herbs, acoustic light wave treatments, contact dermal reflexology, even coffee enemas[14] (my wife and I joke that such a cure would violate the Word of Wisdom). Dr. Lester Bush, in his excellent book, Heath and Medicine Among the Latter-day Saints, explains that this dubious LDS attraction originates in the 19th century when Mormon leaders encouraged members to seek “herbal remedies” when blessings failed.[15] Clearly this made sense at a time when medicine was still in its infancy, and the medicinal treatments and bloodletting then employed were frequently worse than the disease. However, writes Bush, “even today a legacy [of this thinking] remains evident in the practices of a significant segment of Mormon society.”[16] Because of this legacy and the tendency of some quacks to use the names of LDS authorities in their literature, the church issued formal statements in 1977:

Sick people should be cautious about the kind of care they accept. . . . Some unprincipled practitioners make extreme claims in offering cures for the sick . . . and in some cases harm them. … At times they assume to speak in the name of the Church and even give “official” interpretation related to health.[17]

When a dying person is left to the machinations of an “unprincipled practitioner” or, even worse, to someone who truly believes in a product that is useless, the results can be to hasten death or to preclude the possibility of dying well.

Median Not the Message

Once I had a plan of attack established for my own illness, and once my chosen therapy was initiated, it was difficult not to become fixated on the time I had left. This can be an obsession for the dying, though one that is not necessarily addressed openly. Often patients with a terminal condition and physicians discuss only the seriousness of the illness and dance around the question of life expectancy, a cold, impersonal, and frightening sounding concept. This can lead to an unhealthy and persistent denial on both the patient’s and medical practitioner’s parts. Consequently, needless, invasive, and painful therapies may be initiated and important family and personal issues and decisions delayed until later in the game than they should.

On the other end of the spectrum is the dying patient who accepts the “median time” left as an absolute number, somehow divined by the physician, which predicts the day and hour he or she will succumb. Much of this confusion is due to our generally poor understanding of statistical concepts. The median life expectancy (or the time when 50% of patients with a given condition are alive and 50% dead) is a mathematical construct. It is derived from the data of hundreds, even thousands of patients with a similar diagnosis. The data allow for the patient’s age, the stage at which the disease was discovered, the “grade” of tumor (if there is one), and the patient’s overall physical status. But how long a given patient will live is highly individual and dependent on each patient’s history, his response to and compliance with therapy, the use of new protocols, and more ethereal things such as the will to live, a need to resolve personal or family issues, or perhaps the desire to reach a certain anniversary or milestone. Not to be overlooked are emotional support and counseling from family and professionals. One study conducted at Stan ford University examined the effect of psychological support on the seriously ill. Women with metastatic breast cancer were divided into two groups. In one group, the women were encouraged to take control of their lives and examine their fear of dying while the other group received no formal psychological support. The supported group experienced less pain and lived, on average, 18 months longer.[18]

A median life expectancy allows a patient to get a general idea of the aggressiveness of a certain cancer, but the median life expectancy can change during treatment. I entered radiation therapy with the hope, based on my own reading and on what I was told by my neuro-oncologist, that I had a median life expectancy of 36 to 42 months. But cancers do not read text books. When my cancer turned out to be more aggressive than anyone had predicted, I had to adjust painfully that seemingly fixed and non-negotiable median downward. It was like shaking the foundations of heaven. At the time of my surgery, my neurosurgeon and radiation oncologist explained that my median life expectancy would now be much shorter still. The exact number of weeks I was given is not important (although the concept of “weeks” got my attention). But this time, I was able to avoid marking a certain date in the year 2000 as my mortal terminus. Or, given my cancer’s behavior, to even anticipate surviving into the new millennium. I would like to say that I had learned the importance of the old saw about living day to day, proceeding with the assumption of life and with gratitude for whatever time I have left, but that was not always true.

Planning: The Advanced Directive

At some point, we, the dying, need to put our houses in order, and the necessary planning should be conducted with loved ones: a spouse, family, and close friends, anyone who needs to know our dying wishes. It should include details of personal finances, of how we would like to die, funeral arrangements, and our hopes for those who survive. My wife and I did all this. Still, we have had to laugh when people ask us, “What are your plans?” Before this tumor entered our lives, our plans were clear: stay in the Army a few more years; move to a nice community somewhere in the western states; enjoy a comfortable life; proceed with a satisfying career; raise our three well-adjusted, highly successful children; and continue to do the Saturday soccer thing.

Now, our plans change daily with my evolving clinical status, the uncertainties of our financial future, the needs of the children, the in comprehensible military and VA medical retirement and benefits procedures, and the availability of health care. Planning to die is not easy, but Leesa and I have talked openly about perhaps the most important aspect: an advanced directive. This is a formal document which outlines, as clearly as possible, my wishes regarding medical care should I be come unable to make further decisions for myself. This includes my de sires about nutrition, hydration and tube feedings, pain management, the continuation or cessation of diagnostic tests, the use of medications that may prolong my life, the medical procedures-if any-I would allow, and the use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation should my heart stop beating.

This document, although very important, should not be viewed as set inviolate. The patient’s clinical status may change. And some may find it uncomfortable to write down specific instructions, choosing instead to rely on the experience of the doctor, a hospice organization, or on family wishes. But no matter how detailed an advanced directive may or may not be, it will communicate between the dying person and his or her family. This single step should be taken early. It will help ease the fear, confusion, and overwhelming sense of responsibility family members face as they watch a loved one approach the end of his life.

Quasimodo: The Altered Self

I’ve already mentioned the depression that ensues from a profound sense of loss, not a small part of which is loss of the familiar self while a very altered person gradually emerges. For many, this change is not gradual, but occurs due to some devastating event, like a major stroke. I, however, felt deceptively great the day I discovered my tumor. I felt healthy and looked normal to others, no outward sign that I had a “time bomb” in my head. I was forced to accept a gradual change in who I was and in my ability to function. By mid January the tumor had already begun to rob me of the use of my left hand: I could tie a necktie and my shoes only with great difficulty. I noticed early that my speech was being affected. Motor control and sensory input on the left side of my mouth and tongue diminished, and I was introduced to the terror of seizures that would attack at any moment, making my left hand and arm shake in a violent manner. These seizures, however, rarely generalized so that my whole body was convulsing. Then, after the major surgery in March, I awoke having had a stroke. My normal walking gait was gone forever, and I was profoundly weak and had only diminished sensation on my left side.

I have come to call this change of self the “Quasimodo Factor.” Some days I feel so deformed I belong in a bell tower. But even more disturbing than the physical deterioration are the changes in mood and personality, changes that are especially troubling for loved ones. These may occur due to grief or as a consequence of therapy or medication. And the medications I’ve taken have had significant side effects: The anti-seizure drugs make me feel sedated; the steroids, manic; the radiation therapy, fatigued; the chemotherapy, green; and for a while the radioactive 1125 seeds, implanted at the time of surgery and dangerous to others, made me feel like a pariah. My poor wife did not know which one of these moods she might encounter on any given day.

Accepting such changes in myself as a necessary part of dying has been overwhelming at times. Perhaps I never will. A year ago, at this time, I performed a cerebral angiogram on a 15-year-old who had been in a motor vehicle accident. I diagnosed a traumatic aneurysm of the anterior cerebral artery. Today, I worry about unwittingly drooling ice cream out the left corner of my mouth.

In the Cathedral

I have mentioned that during that initial shock of learning I had cancer I did not blame God nor ask him for an explanation. I’ve even maintained the assumption that he loves me, and this has been a blessing. Establishing and maintaining this attitude has been my greatest triumph thus far and it is the most important advice I can give. It avoids an unnecessary, early barrier between the dying person and his Creator. My belief in a divine force in the universe was not destroyed on November 12, 1998. It was my fascination with the Creator’s universe that had brought me to science and medicine as ways to grapple with its many mysteries. Faulty DNA, cancer, and, yes, death I accept as parts of the universe. I cannot claim wonderment with all the natural processes around me and then deny that I am inextricably enmeshed in these. It is a package deal.

This does not mean that I’ve let God off the hook. When I learned I would die, I returned like a prodigal son to my Mormon experience, not to find God, but to rethink his role in my life. Only once during that first week in November 1998, did I kneel and ask God to heal me. But never since. God is aware how much I love this world and would love to stay. I know that if he could, and it were in the cosmic cards, I would stay. But I believe God’s ability to alter natural processes is limited. My conclusion then is a view of God as a partner in this process, someone who understands.

Instead of approaching God as an incessant petitioner, asking him to serve as my neuro-oncologist, I have for some time enjoyed prayer more as communion. When I was receiving radiation therapy over a six-week period at UCSF, Leesa and I stayed in a temporary apartment. On several occasions during this time, I would walk the block and a half north to St. Dominick’s Catholic Cathedral. This is a beautiful building which was damaged in the 1989 Bay Area earthquake, requiring that flying but tresses be placed around the cathedral (an ancient design remedy for a new threat). As I stepped into the cathedral on some nights, I would pass several homeless people sleeping on the back pews, covered in newspaper. I would find myself a secluded spot and spend several minutes looking up at the vaulted ceiling and the elaborate celebration of Christ’s life around me. Then I would thank God for all I have been able to see and experience during my life and ask for his understanding, forgiveness, and comfort. In my experience, those who ask God to influence neutrophil counts or the size of lymph nodes are setting themselves up-if he fails to deliver-to force a wedge between themselves and God. It makes each medical test or procedure a test of God’s love.

Although my belief is that God can only do so much, I have welcomed other people’s faith in intercession. I accept friends’ and family’s promises to pray for a “miracle” (which for me would be simply one more good day without a seizure). I appreciate and find humbling Mormon friends who have placed my name on the prayer rolls of temples. I find comfort in the sentiments of my Jewish friends in San Francisco and of my Catholic friend in El Paso, who tells me she prays for me to the Vir gin Mary. I even learned that an angiography technologist I’d worked with during my residency placed my name on a prayer roll in his Budd hist temple.

As magnanimous as all this sounds on my part, there are comments people make that rub me wrong—cliches like “keep the faith.” It’s a flip pant remark that even the well-wisher has not thought through. During my mother’s illness, more than one person suggested arranging a blessing from a higher LDS ecclesiastical authority, as if there were a hierarchy of blessings which would, of course, depend on the status of one’s personal contacts. Such a suggestion presupposes the blessings I had already received, even touching personal blessings from my father, were somehow inadequate.

Will miracles occur for me? Will this cancer simply dissolve and leave me wiser but whole? I wish it would, but the few formal blessings I have received I recognize, not as interventions, but as messages of love and concern. They have brought peace during a turbulent time in my life, helping me to heal from within. Meanwhile, the modern LDS approach to healing the terminally ill appears entirely pragmatic; that is, we go through the motions of healing, of invoking divine power, but it is mostly ceremony. The patient is really left to God’s apparently capricious mercies and also with the telephone number of a good surgeon. This pragmatism emerges from the reality of the natural course of human disease and the limits of modern medicine. It also comes from experience. A couple of years ago, I sat in a Priesthood meeting in the Golden Gate Ward in San Francisco, listening to a lesson on “gifts of the spirit,” including the gift of healing. At one point the instructor, a third-year dental student, asked if anyone had a personal example of any miraculous healing by the laying on of hands and the anointing of oil that he would like to share. There was a very long, awkward silence. Then one person said he thought there were healings, but that they were either too sacred for those involved to discuss, or the healings occurred in a way no one recognized. Another person told an anecdotal story of a healing that he had heard a friend of a friend relate. I did not have any personal examples either.

From the beginning, Mormons have accepted a certain degree of failure with healing the sick and have deferred to the ultimate power of the almighty.[19] “Some are much tryed,” writes Wilford Woodruff, “because all are not healed that they lay hands upon but I do not feel so. I had a case during Conference concerning the case of Sister Baris. She was sick & I laid Hands upon her & blessed her with life & health & went to meeting. In an hour I had word that she was dead. It did not try me. The Lord saw fit to take her & all is right.”[20] We are often told to heal the sick, that we have the power. In my experience, that power to alter the course of disease is limited at best. The consequent LDS pragmatism was perhaps summed up best by Apostle Neil Maxwell speaking at the Utah Cancer Survivors Rally held on June 6, 1999, in Salt Lake City. At this writing, Elder Maxwell’s own health is seriously threatened by a recurrence of leukemia. But he has served as an example of poise and hope for cancer patients. In his talk, he mentioned his oncologist and also divine healing, but only as footnotes to his theme, which was that we should not ask the question “why me?” but instead live with “cheerful insecurity.”[21]

I find the insecurity part easy. It is, after all, the human condition, and even those of us not facing terminal illness cope with our fear of living by simply not thinking much about what lurks in the shadows. There is an illusion of security that is born out of necessity: No one could survive for long emotionally if each day were spent consumed by the knowledge that ours is a universe that strikes down even righteous people in horrid ways. Yes, in the back of our minds we know that the rain falls on the just and the unjust alike, yet we want to think that, if we play by the rules, we will somehow be protected, rewarded even. Yes, daily we see the reality of divine justice gone amuck in the mindless suffering of the innocent, yet we hope that there is a special cosmic clause exclusively for us. We don’t have the energy to play the rebel, at least while our cattle and kids and skins are intact. With strained smiles, we will live the lie, hoping that the dark angel will pass us by.

But the angel always comes. It’s that certainty that can nudge toward insanity. And the “cheerfulness” Elder Maxwell describes, and of which I have enjoyed a measure, is surely a manifestation either of emerging madness or a true miracle of divine healing.

Argentinean Pears: The Gift of Others

Meanwhile, the people around me have blessed me most by their concern and their many acts of service. From that first flurry of tele phone calls from family, friends, ward members, and neighbors, Leesa and I have received warmth and love and support. For two relatively shy people, this has been sometimes overwhelming. Approaching someone with a serious, life-threatening illness can be terribly awkward. It is also embarrassing to the one who is ill. I remember my own hesitation and often failed attempts to connect with a woman dying of a brain tumor in my Maryland ward. I am no paragon of charity, but I know that people want to heal, to make the bad thing go away. Since they cannot do that, they feel perhaps disingenuous when they offer to help “in any way they can.” But those words alone can, in fact, bring a great sense of peace, and supportive people do play an enormous role in anyone’s attempt to die well. I owe a staggering debt to my wife, who could never have guessed she would have to face such a burden so early in her life. Leesa has led the way with unconditional care and loving attention to my many, many needs. This illness has transformed our relationship, increased our reliance on each other. It has also increased our reliance on the words of other people and on the little and not-so-little acts of ser vice that have humbled us and forced us to wonder how we will ever repay.

I cannot possibly list all the generous and thoughtful acts. They seem endless, and I’m sure I’ve forgotten the majority, but they include rides to the airport, babysitting, Argentinean pears from a friend I had not seen in 12 years, help on a camping trip with my son, a visit to a four-star restaurant, dinner dates, a ride across the Golden Gate Bridge in a ’62 Corvette the day before my surgery, heartfelt letters, a long line of visitors in hospitals in San Francisco and El Paso, a recipe for ginger pan cakes, a generous disposable fund set up by friends in Maryland, a double date to see Dr. Stranglove, grapes from a neighbor’s vine, words of love and encouragement to my father, a trip for my kids down the Logan canal, next-door neighbors who epitomize Christian service, and phone call after phone call after phone call. The list continues to grow.

Of course I would gladly give up all the trips and kindnesses and calls, the money and the gifts (except perhaps the Argentinean pears) if I could stay a little longer. A full lifetime would be nice. But these moving expressions of solidarity and love make the journey less lonely. And because of my situation, perceived rightly or wrongly as tragedy, others have freely divulged to me very personal stories of their own suffering or the suffering of their loved ones: tales of cancer and cancer deaths, which they felt I could understand and appreciate. Everyone seems to have a story to match or to exceed the anguish of my own. I consider such confidences to be a great privilege as they have reminded me of the obvious, sobering reality that I am not in this alone.

The Healing Smiles: Only the Good Die Young

Leesa and I have found humor to be a powerful ally during our ordeal. Early in our relationship Leesa learned to expect dark humor and scatological banter from her medical student then physician husband, even during dinner. It didn’t take her long to return in kind, and on occasion she surprised and outdid me with her own needle insights and her readiness to face my illness with biting sarcasm. This is not a form of denial, a tortured attempt to exorcize a morose circumstance. Humor has always been a part of our lives. Why shouldn’t it bring us a measure of pleasure and exuberance now. After all there are upsides to my situation: I do not have to worry about seat belts, red meat, butter, or the so-called “Y2K” problem, and because this cancer will take me at a relatively young age I do not have to worry about bifocals, buying a late model Cadillac, wearing Bermuda shorts with black socks, irregularity, or Viagra®. I can leave instructions to play Billy Joel’s “Only the Good Die Young,” at my funeral.

I affectionately call my radiation therapy the “Homer Simpsonization of my brain.” Leesa and I blame my hair loss on a radical haircut in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district. Before I went under the knife last March, she asked my surgeon to at least preserve my ability to do dishes. After the surgery, I asked her to hold up a picture of former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, and told her that if I cringed, she would know they had not taken out too much brain. (I passed the test).

The need for a good laugh, or at least a smile, extends to others as they offer comfort to the terminally ill. I do not believe there is some requirement for those dealing with the dying to pause and check humor at the door before entering and only to speak in hushed voices. Obviously the dying should set the tone for any conversational exchange, but I at least have found mostly healing in laughter. I even encourage my kids, who call the T-shaped scar on my head the “T for tumor.” When I grew weary of their talking about my “bad” left side (after all, I hadn’t done anything evil to merit a stroke), we decided I have “superman” on my right and “linguini man” on my left.

Closure: Dying as a Group Event

I have, at this point, a vague idea of what “closure” means. Evidently this is something vital the dying person must go through with those around him. To me it seems very frightening as it represents the penultimate step to the grave. It also implies some grave responsibility, and that is hard to take.

The point seems to be that dying is a group activity, with the inner circle of loved ones needing to heal and reach resolution with the dying person. They too experience the stages of grief, the suffering and loss. In this sense it is not “my” tumor or “my” seizures or “my” fears and frustration alone. This kind of thinking may be a mistake. Perhaps closure with friends and extended family will require only a smile, a touch, some recognition that our lives were interwoven. For those closer, I foresee a much more difficult culmination. This is especially true of my wife. At some point I must say good-bye to her. I cannot fathom what that will be like. How do I “close” a relationship with my soulmate, a relationship I thought would last forever? Somehow, before I finally let go of her, we must prepare to go separate ways.

Hospice organizations have a list of five things that must be said during the process of closure. They are: “I forgive you”; “forgive me”; “thank you”; “I love you” and “good-bye.”[22] In theory this sounds helpful, a tidy list. But I don’t know exactly when I’m supposed to say these things or how or to whom. What is clear to me is that closure is not an event or a single conversation. It is a process, often painful, of reaching for a definitive, hopefully rewarding capstone moment with those who have walked closest to me. But for Leesa, I must do and say all this and so much more. I must not only reach closure, but let her know that with my passing, new doors will open for her, not the least of which is the possibility of remarriage to someone with whom she can grow old and walk the full distance of life. I will have to say goodbye and know that I am also letting her go.

At some point, I will need to reach closure with my father and two brothers. I have a vastly different relationship with each. It is not clear to me how much my oldest brother David, who suffers from chronic schizophrenia, understands of my illness or its seriousness. Closure with him will be difficult only because his illness has prevented any meaningful openness for nearly two decades. My brother John has been deeply affected by my illness, and I have appreciated his words of consolation. John is the only brother left now to seize the day and live a full, meaningful life. Closure with him must include my sincere wish that what has been denied to David and me will be granted to him. And as for my father, I feel the omnipresent need to ask forgiveness for the pain this ill ness has caused. I never wanted to misfire in the revolver of life. His anguish is testimony enough of the enormity of his love.

What closure will entail with my children is a big black box right now. More and more I feel as though they have been on loan to me. And while they have all been very conscientious about my needs and limitations-helping me carry things, opening packages, forgiving me when I need to rest-each has responded to my illness differently. Little four year-old Miranda always blesses Daddy’s “bad leg,” as if its healing would solve all my problems. Six-year-old Drew told Leesa this summer that he loved her, but that he loved Daddy more, “because he has a brain tumor.” And nine-year-old Katie, who understands best, has graduated to the formulas of adult wisdom. Not long ago, I was muttering to myself about how life was unfair. “Well,” she responded, “whoever said life was fair?” Whatever I finally say to them, as I try to let go of everything I so desperately want to hold on to, I know I must not make up stories or assume they do not know what is happening. Honesty will, I hope, best prepare my children for this separation I fear most. What impact my passing will have on them I cannot say, but I can hope that Kubler-Ross is prophetic when she writes:

Children who have been exposed to these kinds of experiences—in a safe, secure, and loving environment—will then raise another generation of children who will, most likely, not even comprehend that we had to write books on death and dying and had to start special institutions for the dying patients; they will not understand why there was this overwhelming fear of death, which, in turn, for so long covered up the fear of living.[23]

Morphine: The Immediate Embrace of God

Perhaps the greatest fear that must be faced as the end draws near is pain. Many assume that pain, even excruciating pain, is common and to be expected, especially in cancer patients and those at the terminal stages of chronic illness. Fortunately, with very rare exceptions, pain can be effectively managed. The blame for failing to do so for so long can be placed squarely at the stone feet of the medical establishment. Until quite recently there has been a tradition of misinformation about and misuse of opioid (morphine-like) painkillers by otherwise competent physicians. Many physicians have expressed concern that a dying per son might become “addicted” to morphine, or they have worried about depressive effects on respiration that may hasten death.[24] Thus, physicians have made the conscious decision that profound anxiety and desperation due to intractable pain are somehow preferable to “giving the patient too much painkiller.”

Fortunately, the tide has shifted and most doctors who work with the terminally ill understand how to prescribe adequate narcotics. Ira Byock writes:

Medicine, especially the emerging discipline of palliative care, has de- vised a wide array of medications and techniques to alleviate even the most profound and persistent pain. Eighteen years of clinical hospice experience has [sic] taught me . . . that physical distress among the dying can always be alleviated. Medical care for the dying stops working only when we give up. Pain is uncontrolled until it is controlled.[25]

I caught a glimpse of the importance of pain management when I was treated for the severe pain of a deep venous thrombosis of the leg and pulmonary embolism (blood clots in the leg and in the lung) after my surgery in March. The medical team working with me set up a PCA (patient-controlled anesthesia) pump through an IV line that allowed me safely to self-administer morphine. More importantly, the team listened to my complaints. Pain, I know indelibly, is what the patient says it is. There were exceptions to this positive experience. Once I was off the PCA pump and on oral morphine, I had at times to use my diminishing clout as a physician to terrorize nurses who had let me wait over an hour for pain medication while they were on break. When patients feel they are begging for pain relief, they become anxious, fearful, irritable, and sleepless, none of which makes it easier to die gracefully. But when morphine or morphine-like medications are given correctly, the dying patient feels in control and is more likely to die well. From my own experience I can say morphine is the closest thing we have here on earth to the immediate embrace of God.

As an intern, I was once challenged to assist a patient with end-stage rectal cancer in his wish to die at home. Because of his cancer, which had begun to eat through the skin of his perineum, he was in excruciating pain, requiring large amounts of morphine. Through the help of an anesthesiologist, however, and home health services, we successfully discharged him with the largest amount of outpatient morphine ever recorded by the hospital. The authorizing premise was that there is no maximum dose of pain medication. The right amount is that which relieves the pain.[26] It was with a great deal of satisfaction that I learned he had died peacefully two weeks later in his home. Mission accomplished.

Wiping the Ass

There will come a time in my dying when I must rely on others to shepherd me to that last breath. Meanwhile, I am acutely aware that I must lose much more function, independence, and ultimately awareness as I approach the final moment. At some point I will be wheelchair bound, then bedridden as slowly I go to ground. I will require increasing doses of decadron, a corticosteroid used to decrease swelling around my tumor. This will make my appearance change as my face will become fuller, the typical Cushinoid “moon” face of chronic steroid use. I may become severely disabled from a stroke or intractable seizure. And I will undoubtedly experience progressive mental decline.

Eventually, like all dying patients, I will surrender to others the management of basic bodily functions, including waste elimination. To the dying, such loss of dignity and control is very frightening. They are embarrassed and aware of how uncomfortable they make others feel. In the popular book Tuesdays with Morrie, Mitch Albom records his ailing college professor’s thoughts on life and dying as he fades from amyolateral sclerosis (Lou Gerhig’s Disease). In an interview with Ted Koppel on ABC-TV’s “Nightline,” Morrie Schwartz was asked what his greatest fear was as slowly he lost the ability to care for himself. “Well, Ted,” he responded, “one day soon, someone’s gonna have to wipe my ass.”[27]

Although I share Morrie’s concern, my greater fear is that I will not be aware the wiping has taken place. This loss of awareness is what I most fear about dying. It is the inability to interact, to voice concerns, to know what is going on. And, in fact, what I dread most may be my precise fate when finally I die. And perhaps that is just as well. I am probably too much of a coward, despite my claims to theoretical and professional preparation, to face the Reaper head on.

Whatever our personal fears about the final stages of dying (pain, loss of dignity, loss of awareness), healthcare givers and caring families who rally around the dying do not dwell on what a dying person may look like or how often he or she must be changed. There is dignity in death. Although difficult, we must relinquish the idea that our bodily functions, the smell and reality of our humanity, are something for which we must apologize. I remember well a young teenager dying of lymphoma in the ICU at the University of Chicago. His parents wanted everything possible done for him. Although his body had already given up and he did not even look human, with fluid oozing from him at every point, his parents never gave up hope, never ever turned away in dis gust.

Kenosis and Letting Go

M. Scott Peck uses the theological term kenosis or the “emptying of oneself” to describe that final act. It is a process of giving in to a higher force, acknowledging our participation in a greater plan:

The process of kenosis .. . is not to have an empty mind or soul, but to make room for the new and even more vibrant. The kenotic individual in Christianity is that of the empty vessel. To live in the world we must retain enough ego to serve as the walls of the vessel, to be any container at all. Be- yond that, however, it is possible to empty ourselves sufficiently of ego that we become truly Spirit-filled. The goal is not the obliteration of the soul, but its expansion.[28]

After my medical discharge from the Army, as I made my final journey from El Paso to Utah, we stopped at the Grand Canyon. I recalled the week I had spent as a boy scout, hiking from the south rim to the north rim and back. It had been an inspiring event for a 13-year-old. Our in significance and short perspective were etched in the ancient multilayered rock on the canyon walls. I was somber on this, my last visit there, aware perhaps for this first time of just how much I will give up with my death. Could I let go of this world? Perhaps kenosis was not for me, not for me to turn my back on the canyon and the achingly material beauty of the world, but somehow instead to turn toward the canyon, step over the rail, and let go. This is my hope, my counter-kenosis, my surrender to the ravishing mystery of this world to/z’// up with it. It is my hope that my family, who are obliged to watch me at the rail, will let me fall.

This may mean taking action. Depending on an advanced directive, the family may choose to withdraw life support, even to the point of malnutrition and/or dehydration in the loved one. Contrary to perceptions, and as those in hospice know, neither is a horrible way to die. Malnutrition and dehydration do not increase a terminally ill person’s suffering and can contribute to a comfortable passage from life.[29]

Of course, if death can be made physically comfortable, then the logical next step for some becomes euthanasia, literally the “good death.” I have pondered at what point and under what circumstances I would consider euthanasia, and whether it would amount merely to a cheap substitute for the more “noble” kenosis which Scott Peck describes. Would I be cheating myself and my loved ones of some important opportunity for personal and spiritual growth? For me all answers to this and related questions are riddled with unresolved issues. Peck himself points out there has been little meaningful debate in society about the issue of assisted suicide. Emotion often interferes with understanding. The true role of euthanasia in our culture is obscure as we apply it both to the terminally ill at the end of life and to the chronically, profoundly debilitated where it raises even more vexing questions.[30]

One night I spoke with a 35-year-old woman, the mother of two teenage sons, who, for a brief time, shared a room with my mother in the nursing home. She has had multiple sclerosis for over 12 years, is nearly completely blind, can hardly move, and is totally dependent on others for all her care. She and I-as 35-year-olds might do-compared notes, and I had to conclude that it is surely easier to die of a terminal illness than to live with a debilitating chronic disease and the consequent intolerable suffering. I could not, in my heart and conscience, reserve my own right to assisted suicide and deny that same right to someone suffering as she was.

Meanwhile, the LDS position on euthanasia is clear. The General Handbook of Instructions (1989) says that “a person who participates in euthanasia—deliberately putting to death a person suffering from an incur able condition of disease—violates the commandments of God.”[31] Yet, the same handbook gives freedom to its members to use “passive” euthanasia by withdrawing various forms of life support and not under taking so-called heroic measures to save such a life. And though there are no formal “last rites” in Mormonism, members often pray and blessings are sometimes given for a dying person to be “released” from this world.

While I cannot speak to the larger issue, I can say that for the terminally ill, this forced choice between euthanasia and needless suffering points up our lack of awareness of hospice care. If people understood ad equate hospice care where the concerns of pain management, dignity, home health care, and, most importantly, family and person are adequately addressed, there would be no rush to euthanasia. Death may well be hastened through aggressive hospice care, but so too dies our fear of dying.

The Question of Soul

Unlike most in my faith, I separate my belief in a Creator, a divine force concerned for my welfare, from the necessary existence of my soul. Perhaps this is my medical bent, my biological degree, rearing its ugly head. I have spent little if any time over the past year worrying about my immortality and this is supposed to be the most vexing question for the dying. But for now I recognize it only as a question, ultimately impossible to resolve, though its importance may soar in my mind as I come closer to death.

Mormonism teaches that we are intelligence wrapped in spirit, encased in corruptible flesh. It is the spirit which will rise from the dust. Like my mother, most Mormons have affirmed the question of soul long before death ever comes their way. Conversely, others outside the church may be convinced beyond shadow that the grave is absolute, final ex tinction. Either way, such people appear to avoid existential worry about personal annihilation, the angst at the end of life. But avoiding such angst is nearly impossible when we confront the death of innocent children. From a Mormon perspective, the response to this unbearable pain is clear: The child lives on in a spirit world and, more importantly, the be reaved parents will find opportunity to raise that child in the next life. What a great promise for grieving families. Belief in eternal families is indeed a central tenant of Mormonism and one that stands in stark relief to the prospect of a death in the family.

In contrast, however, I am also moved by T. H. Huxley, who, when faced with the tragic death of his three-year-old son, was forced to reexamine his steadfast loyalty to scientific method and to agnosticism, a term he himself had coined. He turned for consolation to the man he respected yet perhaps disagreed with more than any other, the liberal clergyman Charles Kingsley, who saw no conflict between science and the Christian doctrine of the immortality of souls. In a private letter, Kingsley encourages Huxley to reconsider his doubts and to live his life so as to prepare for a reunion with his son. Huxley responds and thanks Kingsley for his kind words, but questions whether hope in the resurrection is enough. He cannot believe in a thing merely because he likes it. “My business is to teach my aspirations to conform to fact.”[32] Huxley then describes the “agencies” which have anchored his life: noninstitutional religion for morality, science for factuality, and love for sanctity, and, in a poignant ending, he writes:

If at this moment I am not a worn-out, debauched useless carcass of a man. . . . If I feel I have a shadow of a claim on the love of those around me, if in the supreme moment when I looked down into my boy’s grave my sorrow was full of submission and without bitterness, it is because these agencies have acted upon me, and not because I have ever cared whether my poor personality shall remain distinct from the All from whence it came and whither it goes.[33]

To be “full of submission and without bitterness” in the face of the terror of my own death is to me the ultimate challenge of the dying.

In Mormonism, the terror of death is most often glossed over. We concentrate on the principalities, kingdoms and dominions we stand to inherit after death, contingent on our worthiness. We focus on the important “work” that awaits us. By so doing, we make death and resurrection into catechistic checklist items. In the words of Claudia Bushman:

Perhaps no group is as sanguine and cheerful about death as the Mormons. We visualize a simple passage through a veil. We will climb the sky and wander off into the clouds to continue life as we have lived it on earth. Death is not a state, but a threshold we cross to another place to live our lives uninterrupted.[34]

In his excellent essay, “AChristian By Yearning,” Levi Peterson admits viewing the LDS sacrament differently than most other Mormon faithful. Instead of a ceremony to encourage faithfulness, so that we might one day attain “celestial” glory, Peterson looks to the sacrament as a statement of hope:

If Christ has indeed purchased eternal life for humanity, I for one will awaken to this gift with an immeasurable gratitude. . . In the meantime, I will make it the center of my Christian worship to anticipate that gratitude when I partake of the sacrament. . . . It seems a pity to be so sheltered from the terror of death that one’s gratitude for the resurrection is merely dutiful and perfunctory. Perhaps truly there are advantages to doubt. Perhaps only a doubter can appreciate the miracle of life without end.[35]

Some have tried to allay any concerns they assume I might have by suggesting I read various books on “near-death” experiences. I have politely declined. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and these accounts fall considerably short. Alternate explanations seem as believable: changes in brain chemistry, perfusion at the time of death, medications used in surgery to include dissociative anaesthetics such as the ketamines, or atropine, which can cause the sensation of flying.[36]

I do have hope in the resurrection, that through Jesus Christ I will live again. And even if only to toil at some menial desk job in an obscure corner of the cosmos, simple awareness after death-with or without a body-would be the most amazing gift I could imagine. But that which mollifies my fears of death more than anything else is not this hope, but the simple fact that it’s been done before by billions of souls before me. What I am soon to do is not novel. The death of a sentient being is a riddle for those sentient beings left behind. On the bedroom wall of one of Dr. Byock’s patients, a man who, in his opinion, “died well,” a message reads: ” Every death is a door opening on Creation’s mystery.”[37]

The Corruptible Flesh

We are much concerned about the disposition of the soul at death, but the dying person must also decide what is to be done with the flesh left behind. Ideally, he or she will have communicated this decision so clearly that loved ones need not agonize over funeral arrangements. One might assume that since I have been writing more or less in praise of the natural man, I might be partial to displaying my corpse encased Lenin-like as a monument to its ascension from clay to DNA. The oppo site is true. I recognize my flesh as atoms, molecules, and cells which, although a marvelous symphony, will naturally dissolve into the soup from which they came. I find the powerful western cultural reliance on the mortician’s art where hair is styled, color added to lifeless cheeks, and lips sewn shut, grotesque and, in fact, a lie. It is an attempt to reverse the specter of death through smoke and mirrors. Couple with this the price gouging and high pressure sales that funeral homes often use, and the result is a good deal of unnecessary additional anxiety for newly grieving families.

Though not encouraged by my Mormon faith, cremation will be my request, an affirmation that the flesh is transitory and that what is to become of me is not in my hands, but will be decided by nature or by nature’s God. Even the venerable James E. Talmage concedes: “Whether the dissociation process [of the body] occupies ten, fifty years, or more in the grave of corruption, or as many minutes in the rosy bed of the crematorium, yet in either case the inevitable decree is obeyed: dust thou art, and unto ‘dust shalt thou return.'”[38]

In the end dying well may require sensitivity to prevailing cultural practices, which, though ceremonial and expensive, provide comfort to those struggling with the death. I must consider the needs especially of three small children who have seen funerals and might expect and might actually need the closure provided by the presence of a casket. Hence, while I stand grimly on principal here, I also equivocate, loving my children far more than my indignation.