Articles/Essays – Volume 16, No. 4

The 1981 RLDS Hymnal: Songs More Brightly Sung

Any denomination will periodically outgrow the hymnal it has been using. Hymns that no longer fill a need for members of the church, or that no longer reflect the church’s attitudes and goals, must make way for new materials. About ten years ago the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints decided that its 1956 hymnal was already becoming out of date. An RLDS Hymnal Committee was commissioned to begin work on a new volume, and the result, Hymns of the Saints, was published in 1981. Hymns of the Saints is more than just a revision or reediting of the 1956 hymnal; out of 501 hymns and responses, more than a third are new to this collection.

Why did the RLDS Church feel the need for a new hymnal after such a relatively short time? Three major motives seem to have been behind the undertaking. First, the Church wished to move ahead with the times. Roger A. Revell, Commissioner of the Worship Commission at the RLDS World Headquarters, stated, “The late sixties were a period of tremendous theological exploration for RLDSism; many of the texts [in the 1956 hymnal] simply didn’t reflect the church’s posture.”[1] Especially strong was the feeling that the old hymnal did not do justice to the growing sense of mission as a world church. The new hymnal deletes “The Star-Spangled Banner,” for example, and many of the added hymns specifically address the issue of expansion and worldwide fellowship. One such hymn uses Sibelius’s Finlandia as its musical setting:

This is my song, O God of all the nations,

Hymn 315; text by Lloyd Stone and Georgia Harkness

A song of peace for lands afar and mine.

My land is home, the country where my heart is:

A land of hopes, of dreams, of grand design;

But other hearts in other lands are beating

With hopes and dreams as true and high as mine.

A second important purpose was to select new hymns, or revise old ones, so that the language was more inclusive or more doctrinally acceptable. For example, the Hymnal Committee attempted to resolve problems of sexist language whenever possible. The changes are not extreme—”Father in Heaven” is still “Father” — but the texts in the new volume avoid terms that seem to exclude women: “mankind,” “brothers,” “sons.” In most cases these substitutions are fairly easy and straightforward; and if the existing language could possibly give offense to anyone, it seems foolish not to make the revision. For example, “God who gives to man his freedom” retains its rhythm and poetic force when the new hymnal changes the line to “God who gives to us our freedom” (no. 184). In a more familiar hymn the changes may seem a little startling at first, but I would guess that after a few Christmases have passed, an RLDS congregation will feel quite comfortable singing a couple of altered lines in “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing”: “Born that we no more may die,/ Born to raise each child of earth,” instead of “Born that man no more may die,/ Born to raise the sons of earth” (no. 252).

Other language changes were intended to eliminate other kinds of divisiveness or exclusiveness. In this hymnal, “We Thank Thee, O God, for a Prophet” no longer concludes with the smug assurance that “The wicked who fight against Zion/Will surely be smitten at last.” Instead these lines have become “The Saints who will labor for Zion/Will surely be blessed at last” (no. 307). In “Come Thou, O King of Kings,” Parley P. Pratt’s vision that “all the chosen race/Their Lord and Savior own” is changed to “Saints of ev’ry race” (no. 206).[2]

Besides enabling the RLDS Church to reflect its worldwide commitment and to make some important language changes for social and theological reasons, the new hymnal provided the opportunity to include new materials, many of them by RLDS composers, authors, and arrangers. A very satisfying text by Geoffrey Spencer, written as a closing hymn, exemplifies the new RLDS contributions:

Now let our hearts within us burn

As with a cleansing fire.

Your gracious Word has stirred in us

A surge of new desire.

Should vision fail and courage yield

To careless compromise,

Then redirect our falt’ring steps

To braver enterprise.As in another time and place,

Along a forlorn road,

The Lord’s renewing grace prevailed

Till newborn courage glowed;

Our worship here has lifted us

From self-indulgent care

And strengthened us to incarnate

The priceless hope we share.How can we now deny that voice

No. 495

That calls us from within,

Or blindly claim we need not bear

Another’s pain and sin?

In hearts that beat exultantly

Renew your perfect will;

And send us forth, restored again,

Our mission to fulfill,

No matter what the merits of a new hymnal may be, a few members of any congregation will always find it difficult to believe that the old hymn book they have learned to know and love should not be with them through the eternities. The acceptance of this new hymnal was aided by two factors. First, RLDS President Wallace B. Smith provided a tape recording explaining and introducing the new hymnal. This message helped remove some of the inertia among those who were reluctant to make the change. Second, the RLDS Worship Service format allows time to learn and practice hymns, so that the music director can insure that the congregation will explore the new hymnal and learn new hymns. A few of the new items have already become favorites.

With the LDS hymnal as a convenient reference point, it is possible to make a few comparative and descriptive points to give an overview of a few of the most noteworthy features of Hymns of the Saints.

The hymnal is wonderfully eclectic: Lutheran, African, Episcopalian, Russian hymns, and many others are mixed with Restoration contributions; folk hymns are printed side by side with medieval settings. This eclecticism does not extend to hymns from the westward movement, however. Hymns of the Saints includes texts by Eliza R. Snow, William W. Phelps, and Parley P. Pratt, but these are writers who figured prominently on the Nauvoo scene before the historical split. None of the early Salt Lake City composers so important to the LDS hymnal — George Careless, Ebeneezer Beesley, and Evan Stephens, for example — are represented. And although “Come, Come Ye Saints” was part of the first printing of the 1956 hymnal, it was omitted from subsequent reprintings by a vote of the 1958 RLDS World Conference and does not appear in Hymns of the Saints. A member of the LDS church will find an overlap of about seventy hymns between Hymns of the Saints and the current LDS hymnal, but this overlap is not because Hymns of the Saints includes the uniquely Mormon favorite restoration hymns. Rather these overlapping hymns could be found in almost any Protestant hymnal: “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God,” “O God, Our Help In Ages Past,” the familiar Christmas carols, and so forth.

The hymnal includes eleven contributions from the Christian tradition of the Southern United States, a tradition that the LDS Church has not been receptive to up to this point. These include “Amazing Grace,” “I Wonder As I Wander,” “There Is A Balm In Gilead,” and eight others. Eighteen hymns are in a minor key, as opposed to three in the LDS hymnal. Fifteen hymns include chord symbols for guitar or autoharp accompaniment.

And one interesting contrast is that a large number of the hymns, or the settings in which they appear, would likely be dismissed by the LDS General Music Committee for possible inclusion in a new LDS hymnal because they would be seen as much too difficult. Some of the hymns in Hymns of the Saints have no time signatures, some have a descant, some expect the singers to understand Da Capo and Dal Segno repeat markings, or they are written to be sung in canon, or they are just tricky tunes. Yet the feeling of the RLDS Hymnal Committee was that every hymn might serve as a resource for some need, and that to segregate hymns into special sections — choir, men’s voices, women’s voices, children’s hymns — might limit the potential usefulness of some hymn. It is up to each congregation to decide what use — if any — it will make of any hymn.

The indexes of Hymns of the Saints are one of its strongest features. We have all the usual indexes: an author index and a composer index, with Restoration contributors marked with a special symbol; a metrical index, so that texts can be interchanged among appropriate tunes; a topical index, and a first line index. But most interesting of all is the scriptural index. For example, if a lesson or talk focused on the book of Mosiah, then one could look up Mosiah in the scriptural index and find thirty-seven hymns with messages correlating with various chapters of Mosiah.

The 1956 hymnal had a section called Historical Hymns which Roger Revell describes as “a way for the 1956 committee to include hymns about which they felt musically or theologically uncertain. Most of the hymns in that section got there because their music did not meet the committee’s standards; they hoped these hymns would be seen as something apart from the main body of hymnody.”[3] The committee for the new hymnal decided, however, that each hymn would have to be either in or out; if a hymn qualified for the hymal, it would have to do so without apology or special tags. For this reason, the new hymnal omits all but one of the hymns previously consigned to the Historical Hymns section. The one remaining hymn — and Mr. Revell claims he voted against its inclusion with both hands raised — has as its tune “Aloha Oe” (no. 472).

But any mention of lapses in taste should acknowledge some compelling practicalities. Easy though it may be for a highly trained committee to invoke coldly objective standards and point out the artistic failings of a text or tune, the fact is that a hymn may have significance that transcends its aesthetic qualities. If a hymn holds a secure place in the hearts of the members, then it probably deserves a place in the hymnal as well. Of course it would be a mistake to decide the content of a hymnal by popular vote among the church membership, and yet Mr. Revell himself comments that he has had “life enriching experiences” with hymns that he previously categorized as musically inadequate. So the Hymnal Committee did bend. For example, a hymn called “There’s an Old, Old Path” comes right under “Aloha Oe” on my list of five or six hymns that seem to me ‘without question to fall below a minimum aesthetic standard. The first stanza is

There’s an old, old path

No. 158

Where the sun shines through

Life’s dark storm clouds

From its home of blue,

In this old, old path made strangely sweet

By the touch divine of blessed feet.

Yet it is much loved — an RLDS friend tells me that it is especially popular for funerals — and Mr. Revell simply remarks that “less stringent standards” applied to “things that are part of our heritage,” even though “if ‘There’s an old, old path’ had been submitted as a previously unpublished hymn, it would not have made it into the book.”[4]

The other hymns on my lapse-in-taste list are set to dotted-rhythm, fundamentalist tunes in the gospel hymn tradition. In the work of the Hymnal Committee, a hymn text had to qualify first; the text and its message were paramount. Only if a text passed muster could a tune or alternative tunes be considered. Yet no tune could salvage a stanza like

You may sing of the beauty of mountain and dale,

No. 8

Of the silvery streamlet and flowers of the vale,

But the place most delightful the earth can afford

Is the place of devotion, the house of the Lord.

Yet when we note that the author of this text is David Hyrum Smith, the youngest son of Joseph Smith, we have a clue as to why the historical, emotional, or nostalgic values of a hymn may outweigh other considerations.

Many Latter-day Saints who see this new hymnal will have to suppress a good-sized twinge of envy. After all, we’d like to see work on our new hymnal get underway, too, yet at this point, ours exists only in hope, while theirs exists in substance. But anyone who turns to Hymns of the Saints expecting great numbers of hymns referring specifically to Mormon history and culture is going to be disappointed. When I saw the title “O Young and Fearless Prophet” (no. 210), I turned eagerly to see this hymn about Joseph Smith only to discover that the entire first line was “O young and fearless prophet of ancient Galilee.” This incident may tell more about my LDS upbringing than about the hymnal, but the fact remains that virtually all the hymns, those from outside sources as well as those by RLDS contributors, tend toward a generalized religious subject matter acceptable in a wide Christian context. (One of the few exceptions is no. 296, reproduced below.) The trade-off is obvious: if the Book of Mormon, the Joseph Smith story and so forth are downplayed—and there are very few references to such matters in the hymns—then the gain in universality and acceptance means that a certain price has been paid in terms of historical and doctrinal uniqueness. On the one hand it is admirable, as a gesture toward universality and ecumenism, that a Methodist or a Presbyterian would be comfortable with almost all of the Hymns of the Saints. But on the other hand, it is irresistible to ponder what might have happened if authors and editors had decided as one of their explicit goals to exemplify distinctive RLDS history, doctrine, scriptures, and institutions in their new hymnal.

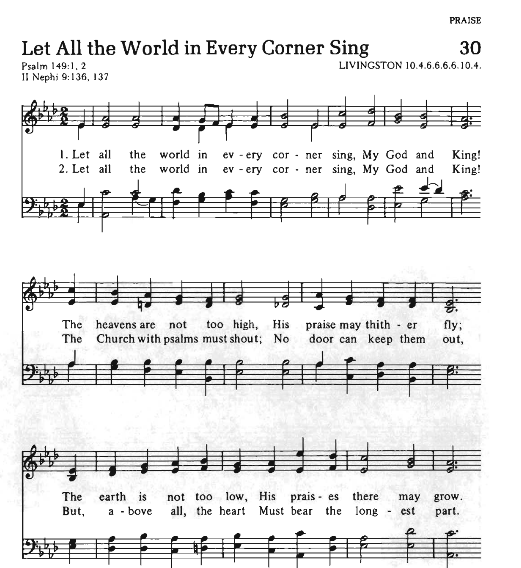

The three selections reprinted here from Hymns of the Saints, are for illustrative purposes only and are reprinted by permission. Requests for subsequent reprinting of any hymn should be directed to Worship Commission, Box 1059, Independence, Missouri 64051. The first, “Let All the World in Every Corner Sing,” combines a text by the English Renaissance poet George Herbert with music by RLDS composer Franklyn Weddle. (Note the listing of correlating scriptural passages under the left-hand side of the title. The word PRAISE, in the upper right-hand corner, indicates the topical division in which this hymn is located; other divisions have such names as “Christ,” “Challenge,” “Zion and the Kingdom,” “The Lord’s Supper.” The designation LIVINGSTON, below the hymn number, is the title of the hymn tune; the numbers that follow give the hymn’s metrical pattern.) The second hymn, “Afar in Old Judea,” offers an interesting text by RLDS writer Roy Cheville, and is one of the few references to the Book of Mormon in any of the texts. Both text and tune of the third hymn, “Go Now Forth into the World,” are by RLDS contributors. The “Witness” and “Benediction and Sending Forth” sections of the hymnal include many such hymns in praise of missionary work. No doubt that is one of the reasons that the loss of “It May Not Be on the Mountain Height,” first relegated to the Historical Hymns section of the 1956 hymnal and then omitted entirely in 1981, was not felt too keenly; new materials had indeed filled the gap so that a traditional hymn that was aesthetically deficient could be dropped.

[1] Roger A. Revell to Karen Lynn, 29 Dec. 1982. Roger RevelFs book Hymns in Worship: A guide to Hymns of the Saints (Independence: Herald House, 1982) gives a great deal of useful information about this new hymnal and about the teaching and use of Hymns in general. A second useful resource is Concordance to the Hymns of the Saints (Independence: Herald House, 1983), believed to be the only denominational hymnal concordance available to the general public.

[2] I cite only a few of the changes here. For a much more complete listing, see Richard P. Howard, “Language Development in Latter Day Saint Hymnody,” Saints Herald, Jan. 1982, pp. 13-17.

[3] Revell to Lynn, 29 Dec. 1982.

[4] Ibid.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue