Articles/Essays – Volume 44, No. 2

The Birth of Tragedy

For Neal Chandler, il miglior fabbro

“Is Mormonism still part of your Weltanschauung?” Aunt Doris asks me every time she sees me. She knows that at 2:15 on Sunday afternoons I’m blessing the sacrament like any other Mormon priest, even though I can be found Sunday mornings at St. James Episco pal helping administer the chalice—“the blood of our Lord Jesus Christ keep you in life everlasting”—and sometimes I even help lay out the cups and saucers for coffee hour. When I drive from St. James to Sacramento Second Ward, it’s like reversing the wedding at Cana—the wine becomes water, the priestly robes turn into dark suits, and the emaciated body of Christ, which at St. James is a wafer, miraculously rises to the texture of Wonder Bread. “That’s the way our parents brought us up,” I tell Aunt Doris for the millionth time. Dad is Mormon and Mom is Episcopalian, so my brother Steve and I were born Mormon-Episcopalians. Five years ago, Steve decided he wanted to be only a Mormon, which Mom and Dad said was fine; but after his mission, he moved in with his boy friend Ramón, and now he says he’s neither.

Aunt Doris forgives me for attending Sacramento Second because she knows that I attend Saturday rehearsals at the McHenry with the same devotion. The McHenry was built when Sacramento was a boom town and a certain Mrs. McHenry (AKA the Merry Widow) couldn’t think of a better way to immortalize her husband than by building a theater in his memory. Now the city of Sacramento owns the building and sponsors all McHenry Company productions. As the artistic director, Aunt Doris insists that we all call it an “amateur company” rather than community theater, and once she sued a reporter from the Sacramento Bee who described the company as “a troupe of loonies and bohemians who spend the weekends smoking pot.” I got involved with the McHenry when I turned twelve; and even though we do have plenty of loonies and bohemians (with Aunt Doris at the top of the list), the only pot I have seen so far is the cauldron we used in Macbeth.

Some in the ward think that Dad, as the family patriarch, shouldn’t endorse my Episcopalian activities, but patriarchy is one of the many Mormon concepts that doesn’t make sense to him. “I had a remarkable dream last night,” Dad told Mom recently at the dinner table. “They released Keith, called Brother Marks in his stead, and the next thing we knew both our children had been officially kicked out of the Mormon Church.” Keith Roberts is our bishop, and he’d rather get released than put me in the hot seat of the Mormon Inquisition. In our interviews he does n’t even mention the E word—it’s all about feeling good when you go to church and living the gospel. But his first counselor, Brother Marks, is a different breed.

One could say that, between St. James and Sacramento Second, I have the best of both worlds. Every June it’s a campout with the Boy Scouts, duty to God and country, and then in late July I go to cool places with the Episcopal youth group, which is strictly coed. We’ve done Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, and once we even went to Baja. There’s little conflict, because at St. James the year revolves around Advent, Christmas, Lent, and Easter, where as at Sacramento Second there are no special Sundays except for general conference.

Mom says it’s good for me to grow up in a mixed household. “It’s like ordering two main courses in a restaurant,” she told me once. “When they bring them to the table, you can smell them up close, get a taste of both of them, and then you’ll know for certain which one better suits your appetite.” She comes to Sacramento Second when Dad and I sing in the choir or give talks. When Brother Marks sees her at church, he always makes a point of shaking her hand with a smile calculated to show her how welcoming Mormons are, but when Mom isn’t there things don’t always run so smoothly. One Sunday he took Dad aside and asked him som berly if the rumor he had heard was true—“that your sister-in-law is a lesbian.” “A thespian,” Dad corrected him. That happened two years ago, and we’re still laughing.

I started my career in the McHenry as the curtain boy at age twelve, then I was promoted to the prompt box, and finally Aunt Doris put me in charge of the backdrops and stage furniture. A few months ago, when I turned seventeen, she endowed me with the additional title of chau-ffeurrr, which means that every Saturday before rehearsal I have to take her shopping. First we get her groceries, then we pass by Props and Frocks, and we always end up at the Salvation Army and other thrift stores that she insists on calling “vintage.” Last Saturday we were looking for helmets and swords, and at Props and Frocks we also got a wax head and some stage blood. Even though we have a tight budget, we buy stage blood because what we spend on blood we save in sweat. With stage blood, the costumes don’t need to be dry cleaned, and most of all we don’t have to hear the building supervisor kvetch about tomato sauce stains on the stage floor. With Aunt Doris’s passion for classic heroines, blood is one of our staples. Last year she played Blanche Dubois (“like a Parisian hooker,” according to Steve). Two years ago, she played Joan of Arc, for which she got a crew-cut like Sigourney Weaver in Alien. This year we’re staging Hebbel’s Judith, and who but Aunt Doris to cut off Holofernes’s head and serve it to the audience on a silver platter?

Aunt Doris attended sacrament meeting with us for Steve’s missionary homecoming, but afterward she lamented that Mormon services are deprived of drama. “When the procession comes down the aisle, when you smell the incense and hear the bells— that’s what I call celebration. Mormon services are the epitome of tedium.” I told her that Dad and I attend the Mormon Church because we feel good about it. “And don’t you see the problem with that?” she replied. “Mormonism is all about feeling warm and fuzzy, which might be a wonderful criterion when you’re scarf shopping, but disastrous when you’re choosing a religion. You need some Brechtian distancing, my dear. You need some Verfrem dungseffekt.”

Steve had met Ramón at Stanford, and sometimes on weekends they come visit. Last Thanksgiving it was the six of us for the first time; Ramón sat next to Aunt Doris, and Aunt Doris was trilling the R on “Ramón” as only a coloratura soprano would. “So, Rrrramón, who’s your favorite playwright?” she asked him. Ra món said something about plays with religious themes—Antigone as a religious heroine, and Hochwälder’s Holy Experiment. His reply pleased Aunt Doris immensely, because for her there’s no language like German and no heroine like Antigone.

“Why, of course,” said Aunt Doris. “Tragedy is always born of a religious impulse. Have you read Die Geburt der Tragödie?” Steve told her she got it wrong—it wasn’t Nietzsche who said that but Lévi-Strauss, and the three of them spent the rest of the evening discussing Carl Jung and the Thanksgiving turkey as a propitiatory sacrifice.

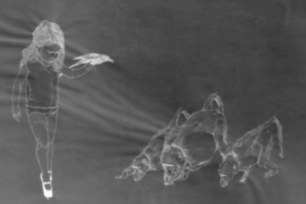

Last Sunday it finally happened. We released Keith Roberts with a vote of thanks and sustained Brother Marks in his stead. Marks didn’t waste any time. Today just before rehearsal, the ward clerk called me to set up an appointment for an interview, and I know perfectly well what’s going to happen next. Marks is going to use the E word. Probably he’ll quote Matthew: no one can serve two masters. Immediately after I hung up, I called Steve to tell him the news. Steve said, “This is the easiest decision you’ll ever have to make in your life.” I hurried to the McHenry and found Aunt Doris off-stage—she had just killed Holofernes and was still carrying the wax head in one hand and a sword in the other. “This is so Oedipal,” she said when I told her. “Don’t you see? You’ll have to kill your father so you can marry your mother.” Then she began to recite the lines she had learned when she played Queen Elizabeth in Schiller’s Mary Stuart:

What mean the ties of blood, the laws of nations?

The Church can sever any bond of duty,

can sanctify betrayal and all crimes—

‘tis this your priests have taught.

As she said it, she was still holding Holofernes’s head by the hair, and those little drops of fake blood were falling on the floor like crazy.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue