Articles/Essays – Volume 18, No. 3

The Black Door

Hyrum Black had three wives. All of the people up and down Tudor Avenue knew that. In fact, I suppose all of the people in Salt Lake City knew that there were polygamists among us, some secret, and some, like Hyrum Black, open. Anyway we all knew he had three wives when he moved in and that he had at least those three until the day he was murdered.

We had all seen the construction of the three identical houses on what had been a corner vacant lot where I played baseball with the Crandall twins and Steve and Jerry Clark and all of the Jensens up until the time I was twelve. We had seen Hyrum himself, dressed in old-fashioned pants made of brown, rough-woven cloth that had buttons on one side instead of a zipper in the front, a shirt with big round buttons, suspenders, and work boots, out supervising the construction with his beard and his cane in one hand, raising his arms and bel lowing commands in Biblical language. We thought he looked like Brigham Young himself gazing down on our valley and declaring “this is the place!”

The day the house was finished, the workers started building the wall, a high, gray stone wall that looked like the side of the Salt Lake Temple, stern, foreboding, and with strange carvings of the sun, moon and stars at cryptic intervals near the top. When the wall was finished, he planted all the way around the outside of it a row of seedling poplars. After that, the only way you could see into Hyrum Black’s yard was by climbing a tall tree, with the ones at Jensen’s being the best because they were the closest. That’s where we stationed ourselves the day Hyrum Black arrived with his three wives and who knew how many kids? You couldn’t count them because they moved around too much, but there had to have been at least seven, because two of the women were carrying babies and there was one tall boy my age or so who looked retarded, and then the twins, boys who looked old enough to be in school, and then there were a bunch of stragglers. The mothers were dark and didn’t talk much, moving silently in their long, dark skirts, except to call out an order now and then in a low voice with words we couldn’t understand.

“Do you think they’re space people?” Jimmy Jensen asked, and we would have hooted him down out of the tree, except that we were trying to be quiet and not noticed.

“That’s Spanish, pea brain,” I informed him. “Mom told me they came up from the Colonies in Mexico.” At the time, of course, I had no idea of what the Colonies in Mexico were; I was just parroting my mother. And actually, even this information was inaccurate, if the tales I heard years later could be believed. According to them, Black had been brought up in Mexico City, the child of a mainstream Mormon banker and his Utah wife. The move to polygamy was something, rumor had it, that his parents never understood, and no one was quite sure whether his costume and ways were something he stumbled on in a forgotten sect south of the border, or something he had invented himself.

“You think you’re so smart, Greg Nelson,” Jimmy told me, his eight-year old ire rising.

“That’s right,” and I gave him a quick Indian burn with both hands on his forearm. He yelped like a coyote and that’s when Hyrum Black noticed us up in the tree and came over to the wall banging his cane and yelling at us to get down. “Way to go, retardo,” I told Jimmy as we scooted down out of the tree.

A few weeks later on Sunday my father woke me up at seven as usual to go with him to priesthood meeting. Sitting beside him on a folding chair in my white shirt and the black suit I was busy outgrowing I heard that my father and I had been assigned as home teaching companions to a number of families in the ward. That meant that we were supposed to visit them at least once a month, make sure they didn’t need anything, give them a message from the First Presidency or a lesson or a scripture, and pray with them, all of us standing around in a circle, before leaving.

“And why don’t you stop in and welcome the Black family—er families—to the neighborhood while you’re out,” Brother Jones ended with a smile. I tried to imagine what a circle it would be if we prayed with my father and me, Hyrum, the three wives, and all the kids, and giggled a little nervously. My father laid a hand on my arm because they were getting ready for the closing prayer.

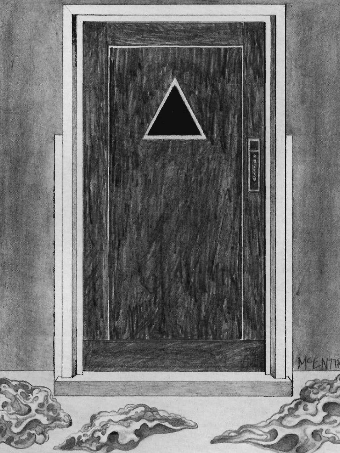

The next night after dinner my father and I put on our suits again and walked down the block to the corner, where the opening in the wall around Hyrum Black’s place could be found. My father knocked. No answer. He knocked again on the dark wooden slats of the door. After a minute or so we heard heavy footsteps heading our way. At last the door swung open, and Hyrum Black, dressed in a brown shirt with a round collar and big buttons, stuck his head out. I mention only that he was wearing a shirt because that was all I could see. For all I knew, behind that heavy black door, his lower half could have been diapered or half-goat or al fresco.

“What do you want?” There was something unused about this way of saying the words.

“Brother Black,” my father said in a friendly voice, holding out his hand, “I’m Brother Nelson, and this is my son, Greg. We stopped by to see if you or any members of your family have needs that we could help with.”

“We do not need anything,” Hyrum Black answered gruffly. “And I would thank you not to call me Brother. We are not brothers in the same faith. Yours is a corrupt and dying perversion of the faith Joseph Smith revealed as a boy of thirteen in 1820.” That caught my father by surprise, I could tell. He opened his mouth, and then closed it again, apparently undecided as to what to say.

Just then a head, small and blue-black like some strange and beautiful summer insect, darted out from under Hyrum Black’s arm and looked at us with unblinking eyes. I had just time to notice the long hair parted in the middle and done in two long, black braids, and the small face with a delicate mouth that smiled faintly on seeing me, before her father plucked her away by the shoulders the way you might hold a butterfly for a moment by the wings, and said loudly into her face, “/Angelica! iVete pa’ dentro ahorita!” And before my father could say anything else, Black turned to us and bellowed, “I will thank you not to come around to my door any more, and I will also thank you to keep your son from spying down on us from the trees!” He slammed the heavy black door shut, and for the next ten years, that door never opened to me again.

***

From the time I was twelve until I turned nineteen I saw Angelica only rarely, and only from a distance: being bundled into the jeep, or running up the street with a sister or two in tow. None of the children went to our school. Did the mother and aunties teach them at home, or did they just work? Were there nine of them now? Or perhaps an even dozen? Nobody knew. Raw milk was delivered to the family in huge containers from a nearby dairy farm, and so were big bags of wheat and bushels of produce, supplementing the carefully planted and weeded garden we imagined out back. During the deer hunt, Black could be seen going out with the tall, retarded son, and they invariably came back with a buck strapped across the hood of the jeep.

“Venison stew again for the Blacks this winter,” Mother said, watching them carry it inside. “And I’ll bet they use everything! I don’t know how they get by!” The truth was, nobody knew. Word was, Black had paid for the construction of the houses in cash and paid cash for everything he bought around town. But nobody knew where any of the money came from, or how he got it, or how much of it there was.

The children came out only rarely; and after the frightening day of the shaken cane, as far as I knew none of us ever climbed the Jensens’ tree again to spy down into the yard. Once when I was fifteen I saw Angelica in a long black dress and a white pinafore that buttoned up the back, her long braids looped under and fastened to her head, on the sidewalk in front of the house with a piece of chalk drawing something that looked sort of like a hopscotch. I watched from my living room window as another, smaller version of her peeped out the gate, then scurried toward her and began pulling on her arm. Angelica shook her head, but her little sister, or cousin, or whatever, kept pulling and gesturing. Then the gate opened again and the tall, retarded-looking boy came out and stood on the little strip of grass between the street and the sidewalk. Slowly he lifted one elbow into the other hand and rested it on his belt buckle, and slowly he put his raised thumb into his mouth. The little girl pointed to him and made gestures of despair, all the time looking up the road— for their father’s jeep? Angelica hesitated, hoppy taw, or whatever it was, in one hand, standing on one foot and then reluctantly lowering the raised foot to the ground again. She slipped the taw or whatever it was into the pocket of her white pinafore, then reached for the arm of the tall, retarded boy and guided him to the black wooden door in the wall without ever jostling his thumb from his mouth. The door swung open and the three of them disappeared.

The life on Tudor Avenue that I remember during those years was a stream of afternoons devoid of mysteries because inside our house, everything was known. It was a stream of afternoons of coming home from school to eat bread and peanut butter and watch “Highway Patrol” or “Sea Hunt” before going out to ride bikes or play touch football over at the church. Those afternoons melted into evenings later of MIA dances where I mostly just stood on the sidelines of the Church gymnasium (only we called it the cultural hall), which was festooned with green and gold crepe paper. It was a time of school plays and Scouting trips and debate meets and then reluctant appearances at any number of girls’ choice dances given by the sororities (only we called them cultural units). As I look back, I have the impression of months bumping each other out of the way in innocent haste as they rushed into years, leaving me scarcely time to breathe, let alone to look at the odd complex on the corner of Tudor Avenue surrounded by the weird gray wall with carvings of the sun, moon, and stars near the top. But it was always there, as I hurried by on my way to the seminary parties or the senior class bonfire or a wrestling match or a music lesson. It was always there, and Angelica was always still inside it—in some part of my mind I knew that.

The poplars Hyrum Black had planted around the outside of the wall grew over the years, and he pruned and shaped them into spearlike perfection around the fortress with the help of the tall, retarded boy. The trees were like a warning, and I believe we heeded it. I don’t remember ever talking much about the Blacks with my friends, or that it ever occurred to us to make fun of the children when we glimpsed them in their clothing from yesteryear and their unsmiling faces. Theirs was a corner of another time and place, of words and ways we couldn’t understand, so we dismissed them from our consciousness—that strange, dark family who openly broke the law of monogamy, but thought of us as the gentiles.

One night in November of the year I was a senior in high school I was walking home just before midnight from Eric Jones’s house, where we’d been working on our debate boxes together. I turned the corner onto Tudor just in time to be hit by a flying rush of skirts that sent me sprawling backwards into a snowbank.

“What!” I called out in surprise. Then I realized that the bundle sliding top over tin cup across the icy sidewalk, something flying from her hand, was Angelica. I scrambled to my feet, dusting the snow from my levis and reached down to help her up. Her black braids were wound around her head now, and the dark eyes looked piercingly into mine for a moment as I lifted her to her feet and brushed at her black woolen shawl and heavy dark skirts. Then she broke the gaze and began looking around.

“Are you looking for what you were carrying?” I asked softly. She didn’t pay any attention to my words, so I went to the ditchside and recovered at last a small, dark object, an odd, pharmaceutical-type bottle, I found as I knocked off the snow, and the dim light from the streetlamp in the next block helped me to make out in funny, old-fashioned letters, “Ipecacuanha,” on a label that had the worn feeling of old suede.

“Here,” I said, turning around and holding the bottle out to Angelica, and she snatched it away from me quick as a night insect darting toward a light, looked into my eyes again for just a second, and then turned and ran across the street in the direction of the black door in the wall, which swung open a second or two before she reached it, then swallowed her up. I stood rooted to the spot for a moment or two, shaken by what I had seen in that last glance from the beautiful young girl who didn’t seem to understanding any of my words and whose pure, dark features were so unlike those of the Nelsons and Jensens and Clarks and Smiths I knew. But even her uncommon beauty and my uncom common innocence could not keep me from recognizing that look immediately and wordlessly for what it was: a glance of pure terror.

I stood there that frozen midnight for more than a minute, debating. Where had she been coming from? And why had she been out alone at that time of night? She hadn’t been to the drugstore, not at that hour. Had she been to the home of another fundamentalist family not far away? And what was in the strange bottle? Was someone inside the high, gray wall sick? Did they need help?

In a moment of courage I now find difficult to believe I crossed the icy street, walked through the eery shadows between the poplars to the black wooden gate and knocked politely. Then I pounded and shook the handle. Nothing. No one. Angelica! I thought in despair. If only I could speak your language! If only I had known the words to make you stop and tell me what you were afraid of! Outside the wall everything was dark and silent, and eventually there was nothing to do but to go home.

Six months later, two days after my high school graduation, I was called on a mission for the Mormon Church to Guatemala. I left more than three thousand miles behind me Salt Lake City, Tudor Avenue, my family and friends and, of course, Angelica, inside her high gray walls with the carvings of the sun, moon and stars near the top.

***

It was springtime a year and a half later when my father came into my room and told me the police wanted me. That, for once, aroused a spark of interest in me, and the green and gold afghan slid off my knees onto the floor.

“They want me?” I asked suspiciously. “Why?”

“I told them you speak Spanish,” my father answered. “There’s something happened down the street at Hyrum Black’s. I think somebody’s dead.”

I got to my feet and ran a hand through my hair, longish over my collar because I’d discarded the idea of cutting it the way I’d discarded most other ideas involving action since I got out of the clinic in Chichicastenango.

“Come on,” my father said, buttoning his sweater. I could tell that only part of his excitement was at seeing me standing up and about to do something useful. The other part was the same thing that moved me: curiosity.

Outside it was early afternoon—something I’d barely realized from the darkness of the room where I’d drawn the blinds and neglected to turn on the lights. It was the same room where I’d been sitting for nearly four months, making excuses to my parents about when I thought I might be ready to start classes at the University of Utah. The earth was just beginning to smell alive again after the frozen months of winter, and Jimmy Jensen’s dad was actually tinkering with his lawnmower in front of the garage. It had been weeks since I’d been outside, and I was warm, too warm even, in the long-sleeved shirt of the kind I always wore now.

At the corner of Hyrum Black’s lot even the fiercely trimmed poplars were beginning to put out leaves. A uniformed policeman was standing at the gate and a couple of plainclothes detectives were standing just inside. I recognized them without being told.

“You speak Spanish?” the uniform wanted to know.

“Yes,” I said.

“How well?” he asked, unblinking.

“Well enough,” I said, not blinking either.

“Come inside,” he said after a moment, and then to my father, “I’m sorry, but you’ll have to wait out here. The family’ll only have what strangers they have to inside.”

As I stepped through the black door in the corner of the wall, I found I was in front of the third of the identical houses, three stone and wooden buildings that looked much smaller than I remembered them from the time before the wall went up. High pyracantha bushes covered with thorns and orange berries separated the three houses, and a neat lawn ran to the edge of the garden on the side of the lot nearest Jensens’ and their fateful climbing tree. On the walk in front of the middle house, two bodies lay side by side, a man and a woman, feet together and arms folded neatly across chests. The man was Hyrum Black, beard grayer than I remembered it, but wearing the same sort of suspenders and homespun trousers and shirt with the rounded collar and big buttons. But it took me a second to realize that the body at his side was one of his wives. In my first, startled glance, I’d taken it for Angelica because of the black knitted shawl, the black braids wound around the head, and the heavy, dark skirts covered by a white apron. But as I stepped nearer, I saw that in spite of the black hair, the woman at my feet must’ve been closer to forty than Angelica’s twenty. The features were different too – broader, more Indian.

“That was my sister,” said a soft voice in Spanish from the doorway of the middle house. I turned and saw a woman who looked a few years older than the one stretched out on the ground in front of me, with a few gray strands weaving through her braids, no apron, and a gray shawl instead of a black one.

“Your sister, or your sister-wife?” I said, not to be impolite, but because I imagined it was the kind of thing the police would want to know.

“Both,” she said. “When Hyrum Black came to Puertas Prietas he asked my father for all three of us, and Father said all right. It has been easier that way, I think. We were already used to each other, used to never having anything that belonged to one alone. It was easier that way, I think. Or at least it was in the beginning.”

“What’s she saying?” The detective held the microphone of the tape recorder toward me.

“She says the dead woman was her sister,” I said.

“Would you like to come inside?” the woman with the gray shawl asked politely.

“I’d be honored,” I said.

“Your Spanish is very good,” she said, and because this was a statement, not a compliment, I said nothing. When my eyes adjusted to the dimness of the interior, I had to bite my lip to stifle a sudden urge to laugh that rose up inside me, because as I looked around the one large room in which I found myself, it reminded me of nothing so much as the living room at the Ponderosa on TV. There was a stone fireplace in one corner, a wooden table, half a dozen pine chairs, a stool, a rocker, a cradle, a churn, a loom, all in the appropriate places. At the far end of the room, a curtain was carelessly drawn over a sort of pantry stacked from floor to ceiling with mason jars filled with canned goods, and in the center of the room a braided rug covered the wooden floor.

“Please sit down,” the woman told us, her features impassive and more Indian than not.

We pulled up the pine chairs around the table; and as the detective with the tape recorder searched vainly for a place to plug it in, I looked around the room and realized with a start that there was someone in the armchair near the empty fireplace. Someone with black braids wound tightly around her head and covered from neck to feet by a heavy quilt, knees drawn up to her chest, chair turned slightly away from us. Angelica. I pulled nervously at my shirt sleeves, but she didn’t even glance my way.

The tape-recording detective gave up on finding a plug and fumbled in his coat pocket for some batteries. At last we were all ready.

“Please tell the woman that I am Detective Keller and this is Detective Charles.” The uniform was apparently waiting outside, guarding the bodies or something. I repeated the information.

“Ask her to tell us, in her own words, what happened,” Detective Keller said. I repeated the request, and so she began:

“My sister, Veronica, killed our husband, poisoning his postum, and then she drank from it too, killing herself. I can show you the poison. And the cup.” She stopped as though she had said everything.

“But why?” Detective Charles exploded. “What could make her do a thing like that? And why didn’t the rest of them stop her? You’ve got to find out more.” Something in the way he asked the series of questions triggered a memory in me. The mission president himself sitting at my bedside in Chichicastenango saying why, why why, over and over again. But I never answered any of his whys except the most superficial ones.

I repeated the questions to the woman before me.

“Hyrum wasn’t always like these last few years,” she said, thinking, I suppose, that this was some kind of answer. “In the beginning you’ve never seen a kinder man, when the three of us came to live with him. Then when we were all expecting our first babies, practically at the same time, well you’ve never seen anybody happier.” Her voice was becoming more sure now, like a wheel that’s been standing for a long time, but that, after the first few spins, finds it can still turn.

“I was the first one to go into labor. It was a hard labor, and I had nobody to help me except Veronica and Ester, and both of them were ready to deliver any day themselves. But at last he was born, and they told me he was a boy and there was a whoop of excitement from outside the door where Hyrum was listening, but then Veronica was washing him and suddenly she made a little gasp. What’s wrong, I asked her, but she didn’t say anything, just brought him over, a tear falling from each eye, and laid him in my lap. Magdalena, she told me, here is your son. It was one of those times when you can’t ignore what you least want to see because it was obvious. The baby was an idiot. That was my Abel.” The word she used to describe the child shocked me, and it was a few seconds before I realized that she had been describing the birth of the tall, retarded boy who accompanied his father on the deer hunts. I repeated the story to the policeman, who looked less than interested.

“Then Verónica had her baby. Angélica.” The woman pointed vaguely to the corner. “At first we were all relieved because she was such a beautiful child, especially her eyes, not like Abel’s eyes at all. But then Hyrum started worrying about her, and finally we all did and he tried some tests and declared to us that she was an idiot too.”

“Angelica!” I burst out in surprise. “But that’s impossible! You just have to look into her eyes to … to …. ” I stopped, suddenly embarrassed.

“We didn’t want to believe it,” Magdalena said. “But as the months went by, we began to in spite of ourselves. It was obvious she was not like other children.”

“You should have taken her to a doctor!” I said without really meaning to.

“Veronica wanted to, but Hyrum said she was our shame, and we would bear her, and Abel too, at home.”

“What happened to the other baby?” I asked suddenly. “The third one; Ester’s baby?”

“It died.” Magdalena stopped, then went on again, unwillingly. “Hyrum said it was a curse on our first fruits. Then Ester got pregnant again, and when she had the twins, things seemed to be all right again. Nothing prouder than an old man who has fathered twins.”

I quickly relayed all this information, and Detective Keller told me to get on with it, to hurry her along to the important parts. I shrugged helplessly, then turned back to the stem-faced woman. “But what about Angelica all of this time! Nobody helping her! She was not retarded, was she!”

“No,” the woman said shortly, “she was not retarded.”

“Then what about her?” I demanded. “Nobody helping her to learn things! All of you treating her like she was,” I paused and then spat out the word, “an idiot! Didn’t you know that if you treat a person like something then they can become it!” I’m not like that, I told Elder Gray, my companion, over and over again. But you are, he kept telling me, and in gradual despair I began to believe him.

“Who are you to judge us!” The woman’s fury snapped out for a second, but she gathered it back. “I am sorry. You do not mean to be cruel, but you cannot know what it has been like, what these last years have been like, for all of us.” As she pronounced these words, the front door swung open, and framed against the light of the outside was the tall, pointed figure I’d seen years before in the same posture: left thumb hooked over his belt buckle, right elbow resting on it, propping that thumb up to his mouth.

“Abel!” Magdalena burst out, then turned to me. “I told Ester to keep the children all together in the house, but Abel is hard to control sometimes. The only one who could really do it was Hyrum, and now that he is gone. . . .” She trailed off, and I tried gently to get her back on track. Meanwhile Abel, thumb in mouth, walked over to the armchair where Angelica sat and towered over her protectively.

“Tell me about these last years,” I said. “Tell me what happened.”

“None of it would have happened,” she said in a hidden tone, “none of it, if we had stayed in Mexico where we belonged, if we had stayed what we were meant to be, but Hyrum found it more difficult every day to be instructed by anyone, to be answerable to anyone. He wanted to be Hyrum Black, prophet, seer and revelator, and not just for his family but for everyone. One by one he shut out all the other families who lived near us, and then he got the idea of coming up here, with a handful of people he claimed were behind him, but I don’t know really if they were or not. After we got here, he forbade us to learn any English, to go out of the house or to let anyone in. Even the others from Mexico we saw less and less often. Are they still here? I don’t know. It was inevitable that with only each other all the time things would eventually go bad.”

How did they go bad? the mission president asked me. I have sinned, President Peterson, I said. How? he said. What does it matter? I said. They are just different faces of the same thing, and they are all ugly. What does it matter so·much which one? “What went wrong?” I asked the woman before me.

“A lot of little things. The way we made the clothes, the way we sat at the table, the way we worked in the garden. He criticized us all. But the one he was the hardest on was Angélica. He loved her the best, but at the same time, could hardly stand to look at her. After he decided that she was not an idiot after all . . . . “

“Fine,” I burst out.

“You are not so smart as you think.” Magdalena gave me a cold look. “Hyrum decided that she was not an idiot after all and then one day he had realized that she was. . . .”

“I can’t believe this,” I said to the detectives, to their odd looks. Then I caught hold of myself. Magdalena was eyeing me, hands calmly folded in the lap of her dark skirt, but clearly offended at being interrupted twice.

“I am sorry,” I managed to say. “Forgive me for interrupting. You were about to say that Hyrum decided she was … ?”

” … possessed,” Magdalena concluded, after a slight hesitation. “That is when he started the exorcisms, the long days of prayers for all of us, the midnight purges.” The incident of the cold November night years before came back to me. “But nothing satisfied him. We should have stopped him, Veronica or Ester or I. We should have stopped him. But maybe we had half started to believe it ourselves. She was so … odd.” I struggled and remained silent.

“At last we thought he had satisfied himself that he had cast the legion out of her because for a long time he didn’t say anything more about it. And she was attached to him, poor, strange little thing, in spite of it all, and so who knew … ” she checked herself abruptly, then went on as if she had turned a sudden corner, “who knew what he was thinking?” Veronica told him he should take her to Mexico and marry her to someone there, and if only he’d listened to her! But he said it was something he would never do. How can I do that to one of my brethren, he would shout. She is our pain, and we will bear her alone.” Magdalena paused, apparently thinking, and I took advantage of it to catch Detectives Charles and Keller up on the story.

“Less Dallas and more details,” Keller said with asperity when I’d finished. “See if you can’t get her up into this decade at least.”

“Hermana,” I said softly, slipping into the mission lingo without being aware of it, “I just don’t see how that explains Veronica killing her—your—husband, and then herself.” And I don’t understand the way you tried it either, President Peterson told me. For pity’s sake, that’s a woman’s way, and I said well, you had to use what you had on hand, didn’t you, and one thing about Mormon missionaries is that we all shaved every day and he said Elder, did you sleep with a woman, is that it?

“It was Hyrum’s idea,” she said, “when he found out what she’d done he said that that was something we couldn’t bear within the family, although the Lord knows he was blind to it the longest of any of us, because even Abel had noticed before Hyrum did! There’s no blind man like he who will not see! But when he finally did, he raged around the house for a week or more shouting that God had punished his family enough and that he, Hyrum, would not stand for it any more, and that the only way to put things right was for Angélica to pay the ransom, and that the only way she could pay it was with her life.”

“What! What do you mean, ransom! And what had she done!” What does it matter, I told President Peterson. What does it matter which of the masks it was that we read in high school to be hated needed but to be seen! What does it matter which one it finally turns out to have been!

“What is it!” Keller wanted to know, and I told him quickly, and then Magdalena went on:

“We talked about it arid cried about it for days, and finally Hyrum called a council, the four of us, him, Veronica, Ester, and I. Angelica sat over there in that chair in the corner while we talked. We all cried, even Hyrum, but in the end he decreed it by the power of his priesthood, and we all agreed to it, that the three of them would eat dinner together, and afterwards that it would be in the postum so that she would die with her mother and father there, because another way would be too cruel.” She looked silently at her hands as I repeated the story to the tape recorder.

“God, it’s just like Jonestown,” Detective Charles breathed.

“But why!” Keller burst out. Why, they asked me in the hospital, why, asked President Peterson, why asked my father when I got home. I only want to know one thing, he said to me tears running down his face, why?

“Why?” I asked Magdalena.

She looked at me in a wav I had seen somewhere before. In the mirror? Then she began slowly to talk again, picking up the thread of the story where she had left off. “So then it was settled. We all went to the other house and sat together praying while the three of them ate dinner in here alone. We were all together in Ester’s house, so we knew it was just the three of them in here, and nobody else. After a couple of hours I couldn’t stand waiting any longer and came over, expecting to find Angélica dead, but instead she was sitting over there in that chair, just like now, and Hyrum and Verónica were the ones who were dead, faces slumped forward onto the table.

“Verónica had said she was going along with it all, but at the last minute it must have broken her heart. At the last minute she must have decided that rather than kill her own child, she would kill her husband, because there was no other choice, and then herself.”

I repeated this to the detectives. “But why did they want to kill her?” Keller repeated. “Ask her that!”

“You still do not understand!” she responded with a sniff when I passed to her the question. “All right, I will show you everything. I will make you understand.” You still don’t understand? I said to my father. All right, I’ll spell it out for you. Father, I told him, I have slept with another man, now how about that? Doesn’t that clear everything up? Doesn’t that make you feel better for knowing? Doesn’t that make everything all right?

“You still do not understand.” Magdalena got up and walked slowly to the empty fireplace in the corner of the room and shooed Abel from the way gently. With a slow, certain movement, she helped the girl in the armchair turned slightly away from us to bring her legs down to the floor and throw off her quilt and stand up. I don’t know much about that kind of thing, but guessed she must have been about six or seven months pregnant.

“Ask her who the father was,” Keller told me. “The retarded boy? Or was it old Black himself? Or was it somebody else we don’t know about?”

“What does it matter?” I turned on him. What does it matter, I said to my father, when all of the faces are ugly.

I turned back to Angélica, and she looked into my eyes, but not with the terror I had seen that night long ago at midnight. Angelica! I thought. You behind your wall and I behind mine ! If I had known how to talk to you then, if I had known you were waiting for me, if you had known I was coming back to you …. She looked at me as if she understood. There was no shame in her look, and I felt mine falling away before her pure black gaze.

“Ask her who the father was.”

I turned to Magdalena again and repeated the question.

“I do not know,” she said simply. “Only Angelica knows that. Or maybe Verónica knew it was Hyrum. Maybe that’s why she killed him. We’ll never know.

“Why don’t you just ask her?” I said. “Nobody ever gets around to doing that, do they?” I stopped surprised, because Magdalena was looking at me with what, if I hadn’t known better, I would have interpreted as triumph. I turned to the detectives and relayed the information.

“Wait a minute,” Charles said as I finished. “Magdalena wasn’t there at this dinner, was she?” I shook my head. “Then how can she be so sure that it was Veronica who changed her mind? You said that Angelica was here in the corner the whole time they talked about it. How can she be so sure that it wasn’t Angelica herself who switched the cups?”

I repeated the question, Angélica de mi alma, although I knew already that it wasn’t true. I had seen from your eyes that you were like me and you knew what it felt like to look at that straight on and not care. We were not born the way we were, Angélica and I, but made. Made to be something that we wouldn’t have been, not really, if things had been different. That’s what I thought or knew or thought I knew before Magdalena opened her mouth to answer me. Then when I heard the words I remembered again what it felt like to be at the point of knowing everything then to find it turned in on itself and ugly like a rubber Halloween mask.

“How do you know that it wasn’t Angelica who switched the cups,” I said for form’s sake, “if she was sitting right there listening to everything?”

“But she wasn’t,” Magdalena said with the suggestion of a smile. “She was sitting right there, but she wasn’t listening. She couldn’t have listened. Angelica is deaf.”

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue