Articles/Essays – Volume 05, No. 3

The Church and the Orient | Spencer J. Palmer, The Church Encounters Asia

The motion picture Mondo Cane taught us that the chronicler’s job is to assemble his collectanea in straightforward reportage. Dr. Palmer’s book is a lucid chronicle (from 1851 to 1969) of some missionarying Mormons turning their faces westward—toward Asia this time. He seeks this missionary work in Asia as the logical extension of our ongoing covered wagon saga.

Although Indochina and Malaysia are considered, China, Japan, and Korea, where church missionaries have done the most work, receive the most vigorous treatment. And Palmer’s handling of Korean materials, which he knows best because of his mission presidency there, is tougher and more resilient than the rest.

Much of the narrative comes from Hugh J. Cannon’s journal, which Cannon kept while travelling with Apostle David O. McKay on his world tour of misisons in 1921. You share his tremulous wonder as he sees for the first time the ancient Asia. And you tremble there on that brink, knowing that like Star-Child of 2001: A Space Odyssey he will “think of something.”

The imperatives to this work are two. First, Dr. Palmer is a pioneer in Church/Asia publications. His books and articles, published since his involvement in Asia as an army chaplain in the 1950’s and during his Korean mission presidency in the 1960’s have established for him a fundamental role in the Mormon dialogue between Orient and Occident.

Second, our Church has become a world Church. Asia is now part-and parcel of our Mormon “we.” Consider the symptoms: The new Church Office Building at Salt Lake bears an oblate bas-relief world on is facades; semi-annual General Conference is now “World Conference”; we saw the Japanese contingent come to the Salt Lake Temple during World Conference this past fall for endowments in Japanese, and must have glimpsed that the Church is at a threshold of building institutional foundations in parts of Asia; we have recorded prophecies that lead us to anticipate sustaining an Asian apostle within our generation; our temples almost daily perform marriages between Asians and Caucasians; we are involved with Americans of Asian ancestry around and about Church headquarters, because their ancestors once built for us a railroad, and we once built for them a war-time relocation camp.

And I remember that when we organized the BYU Asian Students’ Branch three years ago, nobody thought it could work. (“How can Chinese, Koreans, Japanese, and what-not, ever get it together in one branch?”) Yet they did get it together. And people began asking why.

So these are symptoms. What are we to do? Until our ultimate concerns are world-concerns, we are still just lip-reading through the “brother hood” scriptures, and we might as well broadcast rock-and-egg-roll to Asia instead of World Conference.

How shall we tell our new world-fortune? Palmer’s book suggests the beginnings of some Asian answers. Dr. Palmer calls his book “a compendium of principal participants in the unfolding of the Lord’s work in Asia, mostly since World War II. It is a pilot effort, a harbinger work, an overview for the general readership.”

The Gospel scholar will not find in these pages much definitive analysis of how we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land. There is merely the statement that we have begun the singing and a glimpse at some of the personalities who have composed the first measures.

In many ways it is a surprising statement. It includes some startling photographs (David O. McKay in Peking’s cypress grove where he dedicated China in 1921), and some moving scenes (the director’s eye-witness account of filming the Japanese Man’s Search For Happiness for Expo ’70).

So this is a book of people and exuberant human interest (like Gilbert W. Scharff’s new Mormonism in Germany). It seeks a new relevance for what have been the neglected missions of the Church, because relevance must be the operative word in any discussion of our missionary work in Asia (Robert J. Christensen in last Dialogue duly noted). Most soldiers and missionaries can tell you that between us and Asians there have often been great gulfs fixed. We need the sort of “bridge over troubled water” that this book pro vides.

Yet relevance demands facts and long looks at things the way they are. But where does the student go for facts? Sadly, we could type on one page the entire bibliography to date of Church/Asia publications. The Improvement Era, The Relief Society Magazine, BYU Studies, and The World Conference on Records of 1969 all have devoted major space once or twice to works on Asia. The Ensign plans for Church/Asia articles. Dialogue remains aloof.

Dr. Palmer writes, “The full story of the Church encounter in Asia cannot be covered within the pages of one book. Questions dealing with comparative religion—Mormonism and the native Oriental faiths—although of crucial import, must wait for elaboration elsewhere.” If this book is a preface, the future, then, must see book-length treatment on each proselytized Asian country, including histories, methods of proselyting, and experiences of the everyday-missionary-on-the-street. There must be footnotes, bibliography, analysis, colloquium. I recommend that we translate this and subsequent works for use in the Asian missions. We should distribute these among the Asia missionaries, as we have done in the past with Alvin R. Dyer’s The Challenge. And these will be good reading for our Asia-bound soldiers.

We shall need to be exploring two questions: What does twentieth century Asia mean to Mormonism? and What does a twentieth-century Mormonism mean to Asia? These questions suggest a dialogue which ought to interest those now in charge of worldwide Church education.

Until we come to terms with that dialogue, our missionaries are like the Chinese wine-poet Li Po—not that they are drunk, but that they are standing in a lurching canoe and grasping at a reflected moon not yet reachable.

The final chapters of The Church Encounters Asia, including one on translation work, are open-ended, forthtelling, and future-minded. They are saying what should be obvious by now: we are yet to witness the Church’s most exciting encounters in Asia. After all, we still have Russia and Mainland China. . . .

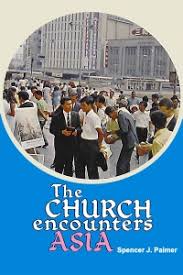

Finally, there is the cover. The cover! It’s right on, Brother Brown. With a cover (not to mention endsheets) like that, which you must see to appreciate, you can allow some redemption for the usual bad Deseret Book typography.

At any rate, here is a book of “the romance and high adventure of the Gospel,” told, would you believe, to the background of an Asian lute, for the real-life missionary, the armchair proselyter, or just anybody who grooves on watching the meiosis of a Mormon community from a safe distance.

Which is to say, Asia isn’t like it used to be. It never was.

The Church Encounters Asia. By Spencer J. Palmer. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1970, 201 pp. $4.95.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue