Articles/Essays – Volume 14, No. 1

The Cloning of Mormon Architecture

Though Brigham Young sermons were often full of exaggerations, he was right on the mark when he said,

To accomplish this work there will have to be not only one temple but thousands of them, and thousands of ten thousands of men and women will go into those temples and officiate.[1]

Brigham clearly envisioned the 6,500 church buildings the Latter-day Saints would have erected by 1980. The architectural history of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints reflects an industrious, proud and diversified tradition in style, technology and objective. Mormon architecture, always responsive to the changing environment, has expressed changes in church membership, tastes, philosophy and the organizational structure of the Church itself.

Historically, Latter-day Saints have had three distinct forms of ecclesiastical architecture: the temple, the tabernacle and the ward meetinghouse. In the nineteenth century, these three types were clearly distinguishable in size, style and function. In the mid-twentieth century, however, when tabernacles were no longer built by the Church, temples and ward meeting houses drew closer in style and character.

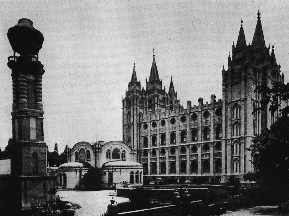

Even in pioneer times, Mormon architecture expressed little that was truly indigenous. Most styles and forms, like the castellated Gothic style of the Salt Lake Temple, were adapted from other historical periods and applied to Mormon culture. The period beginning in 1920 became identified with a growing conservatism and historicity in architectural attitudes and practice, and the early years in this period represented resistance to the modern influences already expressed in the design of the Canadian and Hawaiian Temples.

By the 1930s essential functional patterns of Latter-day Saint worship programs were established that would dictate ward building design for the next fifty years. An increasing number of bishops’ offices, relief society rooms and recreation halls were incorporated into the scheme of one building. The red brick “Colonel’s Twins,” built in the 1930s by architect Joseph Don Carlos Young, embodied this concept of integrated design, which connected the two large masses of cultural hall and chapel by a one-story vestibule. In the foyer, a stairway led to the basement level and classrooms, auxiliary rooms and kitchen.

When a chapel plan was considered particularly adaptable, functional or attractive the same set of plans was used to build a similar building. These first “repetitive” plans were prepared by the church architect under the auspices of the Presiding Bishop’s office, but church leaders had not yet attempted to prescribe certain plans for church use.

In the 1940s and 50s repetitive plans produced by the Church were primarily used by private industry. Ted Pope, through his private architectural firm, designed an estimated 250-300 buildings between 1949-1955, more than any other single architect working for the Church. The standard plans from his offices were chosen because they were popular, functional and inexpensive. Pope had an intuitive sense of the functional limits of his de signs and their response to the needs of church programs. Many of his innovations are still visible in the modern standard plan program. For instance, he initiated the plan which placed the recreation hall adjacent to the rear of the chapel for a more flexible expansion of the main assembly space.

The doubling of church membership in the twenty years from 1940-1960 was reflected in a rapid proliferation of building projects. Accommodation and adaptation in programs and organization became necessary because of the diverse cultures represented in the membership, and the demand for ever increasing church buildings called for a more formal program. Consequently, the institutional response to this need came in 1954 with the creation of the Church Building Committee. While functioning under the office of the Presiding Bishop, control of the building program had been scattered under several different offices. The creation of the Committee, however, consolidated all artistic and financial decisions in a single governing agency. The first official index of church plans was therefore established. Although the Church had used repetitive planning in the past, the first “standards” in architectural types and floor plans were now established and promulgated throughout the Church.

Many architects were alarmed, even in the early years of the program, at the implications of massive standardization. Despite this, growth and the Church’s immediate need to house the members continued to be principal motivators behind standardization. The building missionary program, developed under President David O. McKay, was a response to the demands of the aggressive proselyting effort. Under the direction of the Church Building Committee, building missionaries used standard plans to streamline the building process by saving time, insuring the suitability of church forms and facilitating the uniform procedure of Church programs across the world. Under the building missionary program, standard plans were exploited as an effective tool in the massive building program.

Many saw in worldwide standardization an alarming insensitivity to local cultures and styles. The cry for regionalism in design was common among those who recognized the incongruity of an American chapel in certain exotic settings. Although the Church did attempt to adapt programs to a variety of peoples and their new demands, all members must ultimately worship in the same way. It was felt that if the programs were the same, and the doctrines were the same, the buildings should be the same. The uniformity of design and concept helped to unify different cultures and peoples. Furthermore, for many members the chapel was a symbolic trademark of the Church in their area and therefore their assurance that the Church had indeed arrived.

Most of the chapels built under the building missionary program had been customized to fit specific needs of the local congregation with standard plans developed to fit a variety of situations. Often half chapels or meeting houses with one wing were built to fulfill the particular demands of a smaller branch or ward. When a building was constructed with local materials and techniques, it frequently took on an indigenous flavor incidental to the typical standard design. The Kona Stake Center in Kona, Hawaii, for instance, is one building that clearly bespeaks its island origin. Walls of black native lava rock, rather than familiar brick, and white stucco form a startling contrast with the lush vegetation of the surrounding hillside. The ceiling of the combined chapel-cultural hall space was raised an extra twenty feet to allow air to flow through the horizontal bands of windows to cool the interior. These large bands of glass bring the landscape into full view of the interior, thereby integrating nature into the worship service.

In 1964 the tremendous growth in the building program of the Church, which demanded a more professional approach to building, led to the reorganization of the Building Division and the subsequent establishment of an office dealing exclusively with standard plans. The program was then brought under the supervision and control of the Committee on Expenditures which would make virtually all decisions about building projects. Autonomy on local projects was minimized, and the margin for original interpretation in the design of Church buildings narrowed to a limited number of variables. This completed the transition to in-house standardization. The formerly optional approach to church design became the exclusive method for new church construction.

Naturally the architect of a standard plan project was pivotal in the ultimate success or failure of a project. Encouraged to study the standard plan and specifications as well as the local ward unit itself, he also studied the neighborhoods and the social environment in which the building would be built. The plans were to be closely reviewed and adjusted by the local architect to fit local conditions and requirements: this plan was described as

a guide for the local architect to set forth as clearly as possible the church meetinghouse policy, quality standards and function patterns. The standard plans are to help establish a standard or pattern that can be used in fulfilling universal ecclesiastical programs and needs. They are to help establish a degree of conformity for our universal custodial service program, to save time and money during plan preparation and construction phases and to reduce maintenance costs and problems with our buildings through ongoing experience and feedback.[2]

Modifications of the basic standard plan were usually of three kinds: basic massing, facade decoration and steeple forms. Often a common decorative theme would be repeated throughout the design. The Federal Heights Chapel in Salt Lake City is unified through the repetition of similar angles in all diagonal lines. Because the lines of roof, windows and paneling echo the same rhythms, the chapel creates a feeling of repose and reverence with no discordant elements to contradict the basic unity.

Hundreds of other chapels were built with only minor variations. On several of these buildings a central rectangular facade of cast stone or natural rock was elaborated to conform with local settings. The Heber Stake Center, at Kimballs Junction, Utah, illustrates the potential of even the most elemental structure when colors, textures and materials are chosen with the local environment in mind. The lines and colors of the Heber Stake Center were closely related to the warm earthtones and undulating swells of its mountain site. The steeples of a Mormon meetinghouse were usually freestanding, often repeating some decorative element of the building itself, and often capriciously unique. In fact, they have become more truly individual than any other element of church buildings.

Above all else standard planning was prompted by economic expediency. The responsibility of shepherding the funds of the Saints yielded a conservative attitude towards spending and standard planning appeared to be a solution to many of the problems arising from the Church’s need to begin a one million dollar project every day somewhere in the world.

After its reorganization, the Committee improved the standard plan prog ram by refining and reproducing the plans. By the late 1970s, a complete set of twenty-three working drawings was available for approximately sixty different building plans. On a standard plan project most of the preliminary work was already done by department experts before the plan was given to the architect. This meant too that, depending on the adjustments to site, local specifications and codes, the architect’s fee could be reduced from the basic six percent to two and one-half percent of the total building cost.

Some modifications in standard plan chapels proposed expensive mate rials and others were costly in terms of time as well. Such changes meant that the plan must be sent to the Committee on Expenditures for review, thereby causing weeks of delay. One architect estimated that even with inflation at just one percent a month, or twelve percent annually, each day a project was delayed would cost the Church over $500 per unit of construction.

The Olympus Stake Center in Holladay, Utah, is one of the most unusual original design adaptations on a standard plan. The sweeping lines of the copper-plated chapel roof are reminiscent of a Japanese pagoda. The drama tic movement of the powerful wood trusses of the ceiling repeat the lines of the exterior roof to create an impression of swirling towers. As skylights at the roof peak, the horizontal band of windows along the wall filter light through the room to enhance the illusion of a sacred quiet place. Through the dramatic use of color, line and light this chapel creates a moving atmosphere of reverence and beauty.

But this chapel cost an estimated $9,000 more than the projected cost of the building simply because of delays in approval. If in one year 100 buildings took an extra three weeks for approval, the Church, while perhaps getting 100 unusually attractive buildings, would have spent an extra $1,500,000 because of the Expenditures Committee’s resistance to innovative design.

In its exuberant pursuit of the efficient, economical and functional building, the Church appears to have lost sight of the value of buildings as more than structure. In the attempt to maximize function and minimize spending by economizing on architects’ fees and subjecting designs to vigorous dissection, radical or unique architectural designs have been rendered unacceptable within the confines of the standard plan program. Subsequently, the potential for outstanding individual pieces of Church architecture seems to have been largely eliminated.

The announcement of the proposed design for three new standard plan temples in April 1980 dramatized the problems of standardization when applied to temple projects. The sketches exhibited a radical break from previous temple forms and launched the Church into a new era of mass temple building. Traditionally, temples had been either unique designs or revisions of historical prototypes. The design of the three new temples is, instead, directly related to the rather innocuous style of the basic standard plan chapel.

As in the basic ward meetinghouse, the new temple outlines include a central nave flanked by two single-storied wings. Although the peculiar functional demands of Mormon worship services determined this form forward buildings, use of the same form for a temple is without apparent justification. It could eventually establish a new relationship between temple and meetinghouse architecture. Whereas previous architectural style, size and materials had distinguished the temple from the ward meetinghouse, the new temples narrow the gap between these two main forms. The exterior of the temples in no way reveals the unique ceremonies within, and they have no visual articulation, towers, stained glass art windows or other features to distinguish their sacred functions.

The idea of building smaller standard plan temples reflects the contemporary attitude of church leaders that temple worship should be made available to a greater number of members. Traditionally, temples represented the epitome of contemporary Mormon art and architecture. These conservative, economical, “mini” temples represented, instead, a compromise forged by the strains of the internationalization of the Church, the rapidly increasing membership and the attempt to give continuity and unity to church prog rams across the world.

Secularization of the ward meetinghouse space was expanded by the increasing emphasis on auxiliary functions in modern-day church programs. Although used primarily for worship services, the sacred chapel enclosure was no longer a separate and distinct unit. Combining the cultural hall and chapel spaces for easy flow of traffic between the formal sacred space of the chapel and the informal secular space of the recreation hall created a more flexible relationship between the two. This pragmatic attitude toward sacred space appears to have established a trend towards further exploitation of interior space. In 1979, the proposal was being evaluated for building a half basketball court adjacent to a chapel of the same proportions. Industrial weight carpet, which was used for the surface of gymnasium floors, would be put in the chapel and hall alike. Although the Committee thought this use of the interior space was functionally efficient, it is apparent, at least in this example, that those involved in the study focused on optimal use of space in terms of efficiency, economics and function. Blatant disregard for such con siderations as aesthetics, tradition and the sacred nature of certain spaces allowed the Committee to make a sterile and insensitive design proposal with profound effects on the quality of church buildings. As a business decision, though, this was considered not only appropriate but ingenious.

The fiscal and functional defenses of standardization form a compelling argument, and they exhibit many of the strengths of the program. Why then do so many members feel dissatisfied with the results of the program—the buildings themselves? Why aren’t more of the chapels powerful architectural statements?

Many elements in the policy fostered mediocrity in church design and construction. The underlying ideals of the approach—uniformity, repetition and standardization—are anathema to free architectural expression, and they contradict the basis of any creative venture. When control was taken away from the architect, he lost much of the choice to think independently. The emphasis was not on the ideas of the individual but on collective judgments formed after only minimal contact with artists. Furthermore, the lack of willingness to allow new formal relationships to appear within the vocabulary of standard plan buildings created an atmosphere of artistic malaise in the department’s work thereby inducing a degree of mediocrity in church building.

The architectural determinism of the standard plan program led to arbitrary decisions of taste that were delegated throughout the Church. Consequently, truth in Mormon architecture was conceived in relation to what already existed. Many felt, in contrast, that taste was not a matter of morals and so the right or wrong of architectural trends must always be open to debate.

Within a church that willingly arbitrates on matters of the arts, choosing, regulating and directing artistic tastes and style, albeit in the name of efficiency, economy and morality, what remains but the obliteration of creative thought? With each effort, the exercise of a creative idea is rendered less and less useful; it is circumscribed to a narrower range until it is finally eliminated.

The fruits of the standard plan program are many; its buildings are generally economical, flexible, expandable and spacious. It established a basic continuity in architectural types and materials throughout the worldwide church. But how did it affect architectural design? The departmental approach to architecture does not prevent unique and original design in the Church, but rather it compresses it, enervates and finally extinguishes. The role of the aesthetic in the creation of a Mormon church building becomes only incidental to the design process. Both the successes and failures of the program illuminate the importance of freedom and autonomy in church de sign.

The issue of genetic cloning is an explosive one today. In the same way, meddling in the creative process, forcing out diversity and character, is a formidable danger. The vision of a world filled with thousands of identical ward meetinghouse buildings is alarming. The standard plan program must go in an alternate direction. It must look for changes, varieties, different themes and standards, not to encourage conformity, but to allow the more efficient celebration of the unique, the ambitious and the divine.

[1] Young, Brigham, Journal of Discourses, Vol. 3, p. 372. (Salt Lake City, Utah, 1956).

[2] “Architectural Seminar,” Building Division Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: 4 May 1978), p. 8.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue