Articles/Essays – Volume 02, No. 2

The Coalville Tabernacle: A Photographic Essay

Sometime late in January or early February, winter’s dregs and the rancid crackers of academic routine begin to yield singularly stale sop. During those scraps of days in 1966 both of us turned our mental pockets inside out several times and put all our odds and ends on the table where we could pick them over for our mutual amusement, down to the last snarl of twine and thought. Somewhere in the rich clutter of his mind and notebooks, Doug Hill must have well over a thousand photographic projects. One of them was a study of Mormon churches in Utah. Fidgety of mind and foot in that brown time, we resolved to spend a few spring weekends exploring Mormon architecture.

Our methods were loose. Two sleeping bags, Leica, Rollei 4×5, and other paraphernalia thrown in the back of Doug’s Volkswagen, we made our random way with spring through several areas of the state. Richfield, Annabella, Elsinore, Marysvale, Circleville, Panguitch. Holden, Fillmore, Kanosh, Bea ver. Kingston, Antimony, Tropic, Escalante, Grover, Teasdale, Bicknell, Loa, Koosharem. The mere names indicated a curious motley of chapters for a history essentially monogenic.

Weekends wanned and distended. The two dimensions of a Phillips 66 road map became three, and finally four. Names came to mean valleys and homes and streets and people and, most of all, churches.

By now, the black celluloid sea known only to photographers had engulfed Doug and he was trying to expose and print and develop his way to the surface. Reaching that surface, however, would not prove to be a simple technical matter. For we found ourselves in a sea of larger significance than either of us had anticipated. After two or three trips we were awash with pictures and images of churches and floundering in words about aesthetics, history, religion, architecture, sociology. And beneath, new undercurrents of feeling about the Mormon Church, past and present and future, began to flow.

Fremont, Emery, Ferron, Orangeville, Huntington, Cleveland. Tabiona, Duchesne, Upalco, Roosevelt, Maeser, Vernal. It became a sort of game: reading a name off a road map. Guessing what sort of church we might find in a town of that name and size. Wood frame? Stucco? Rock? Old Brick? Modern red brick? Guessing at the architectural style. Colonial? Schoolhouse? Barnyard? Post World War II Wurlitzer? Neo-Ramada Inn? Indescribable Mormon eclectic? Scanning the line of the town as we neared for a glimpse of the church. Approaching each town with mounting anticipation and excitement, we seldom won.

Our initial reactions modulated with what we found: surprise, pleasure, curiosity, tedium, indignation and, only too rarely, genuine and sustained excitement. And then our hurried, fumbling attempts to get the feel of the building, to classify it, to assess it in terms of the chapels we had already seen, to assimilate it in the Mormon-Utah tapestry of architecture and history and geography being woven in our experience. And for Doug, the attempt to fix those impressions forever in some combination of silver nitrate and self.

We came upon the Coalville Tabernacle on a Sunday morning in July, the last day of the last trip we were to make that year. The weekend had been long. We had spent a rocky night in our clothes and sleeping bags on the banks of the Smith-Morehouse. In the entrails of a breakfast of raw hash browns and soggy French wonderbread in Kamas we read the auguries of a bad day. An overheated morning already threatened us with an oppressive time. Kamas. Marion. Oakley: a stark white chapel among stark white houses and dairy farms provoked desultory visions of Utrillo’s chalkwhite churches in my aching head. The Church of Deuil, “The Little Communicant.” Bleached bones in the body of religion. Peoa. Wanship. Hoytsville. We read the next name on the map and decided to end the trip on exhausted possibilities by driving west to Salt Lake City after this last town. Coalville. We had already visited small mining towns in eastern Utah. What could we expect of Coalville?

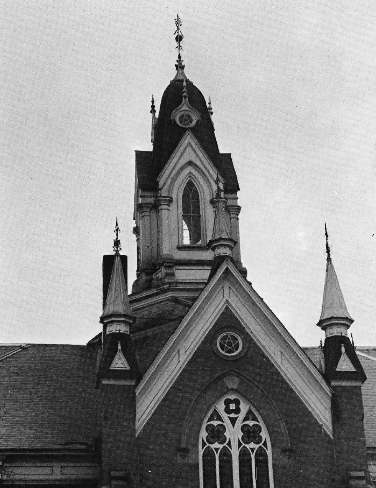

In a rare moment for both of us, our auguries came unstuck. The appearance of the Coalville Tabernacle stunned our sultry mood. Victorian Gothic! Stained glass! A small rose window! Thirteen magnificent spires in Coalville, Utah. Think of that, William Golding! Inside, a Sunday school was in session. Outside, Doug was already laying down a barrage of exposures with his cameras. Two or three malingering deacons followed him as he went round and round the fascinating exterior of the church. At one point, the radically innocent voices of children singing “How Firm a Foundation” accompanied us on our external way. The clear, bright tones radiated deep from within the bosom of the church, melted and fused with the clear, bright day and bathed us for a moment in a strangely soothing balm. I thought for one brief, poignant space of Faust’s Engelchor.

On the verge of exhausting our time and supply of film, we were in the midst of resolving to return for further study of the church when a voice cut through our conversation. “Do you like our church?” We turned to meet a pleasant and unassuming man, a member of one of the Coalville wards whose name we never learned. We assaulted him with enthusiastic impressions. He displayed an obvious pride in his religion and Church and in this chapel. Undaunted by our unsabbatical and unsavory appearance, he invited us to view the interior of the Coalville Tabernacle. We hesitated, but he assured us we would offend neither saint nor sanctuary.

We did not disturb the meeting in progress in the chapel. Instead, he took us up a flight of stairs. Altogether too rarely does a Mormon church provide itself a kind of religious experience, a genuinely religious setting for the essential worship rather than a mere utilitarian shelter. The Coalville Tabernacle does, inside as well as out. Standing on the varnished gymnasium floor built in the 1944 remodeling, we contemplated the original upper half of the walls and ceiling. Three predominant Gothic windows with Mormon motifs and symbols leaded into stained glass. Surrounding and separating them, eight windows with a Victorian jig saw-scroll saw interpretation of classic details. Highly intricate wainscoting. A lavishly painted ceiling chased with ornamental designs and scrollwork, featuring commanding portraits of Hyrum Smith, Brigham Young, Wilford Woodruff, John Taylor. And six brass lamps (formerly kerosene) hanging from this elaborate ceiling.

A stage built in 1944 now cuts off the east end of the upper area of the church where the organ formerly dominated. A fine portrait of Joseph Smith is covered by the crisscross of wires, runners, and drop curtains necessary for stage productions.

The stinging rays of the July sun underwent metamorphosis through the three great windows and now fell in soft splashes of color on the gymnasium floor. Warm browns and clasped hands presiding over the south; roses and lavenders of sunset and twilight and the dove bearing the olive branch presiding over the west; cool, rational greens and a book of scripture, the word, logos, presiding over the north.

We stood taking all this in to the accompaniment of stories of immigrant coal miners from Denmark and England and the other people of Coalville who had raised with bare hands a house unto their God. It was compelling testimony. And we left Coalville that Sunday determined to bear it further.

A few weeks later, minutes of the Summit Stake in the Church Historian’s office told us a story familiar to most Mormons: long years of wheedling, pleading, cajoling, tightening the screws to raise funds so the building could be completed and dedicated.

On a subsequent visit to Coalville, we had the good fortune to meet a man who remembers the building of the tabernacle, Mr. David Barber. He has aged with the Coalville Tabernacle; it is an integral part of his life. For the better part of an hour, he poured out a stream of reminiscences.

The windows were imported from Belgium . . . . notice the wooden steps of the original building and the bell in the stand at their side . . . . the circular part of the window depicting the dove contains one hundred and fifty pieces of glass; the number of days the ark was afloat . . . . there are ten leaves on the olive branch perhaps signifying the ten commandments . . . . and notice the seven pieces of glass re calling the seven last words of our Savior: “Unto Thee I commend my spirit.”. . . . the entrance is on the south side, the clasped hands symbolizing welcome, greeting . . . . Thomas Allen, the architect, was educated to be a Catholic priest . . . . Olsen, the man who painted the ceiling and portraits was an immigrant looking for work. He built a platform. Painted lying down. In some places he used pure gold leaf. He’d pass his hand over his hair for static electricity to pick a sheet of it . . . . notice the lilies painted on the ceiling; “Consider the lilies of the field” . . . . “And the dragon, that old serpent, the devil” . . . . The building was made with care, when erected the walls were plumb within one-half inch. Frank Evans and Walter Boyden hand rubbed every outside brick to polish it. The bricks were made on the site. Sandstone came from the ledge and quarry just east of Coalville. The wainscoting is Washington red cedar, now painted over . . . . the caskets of eleven people of this town once lay in that church. May 1, 1900. The Scofield explosion. You remember. . . .

History is not for the dead. History has been made by the dead for the living. It exists in books and artifacts and ruins, and old Mormon churches. But, by one of the paradoxes of life, it exists nowhere at all if it does not exist in the minds and hearts of men. And it has more to do with religion than most of us suspect.

“Now what is history?” asks Pasternak.

It is the centuries of systematic explorations of the riddle of death, with a view to overcoming death. That’s why people discover mathematical infinity and electromagnetic waves, that’s why they write symphonies. Now, you can’t advance in this direction without a certain faith. You can’t make such discoveries without spiritual equipment . . . . Man does not die in a ditch like a dog—but at home in history, while the work toward the conquest of death is in full swing, he dies sharing in this work.

And that is why people build churches. The Coalville Tabernacle is approaching its one hundredth year. Time passes quickly for people and buildings. We can think of no better way to honor this historic church and the faith of those who built it than to begin to take steps toward its ultimate restoration and preservation. By so doing, we would honor our own faith in a time when we buy our bricks from factories and push handcarts of the mind.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue