Articles/Essays – Volume 05, No. 2

The Conscience of the Village: From “River Saints — Introduction to a Mormon Chronicle”

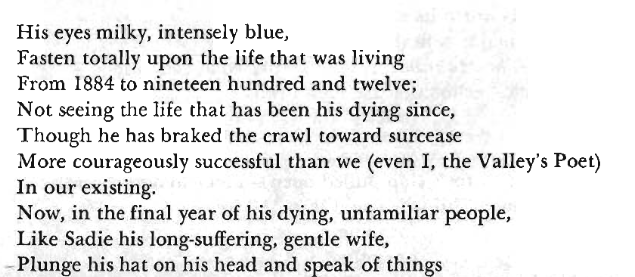

His eyes milky, intensely blue,

Fasten totally upon the life that was living

From 1884 to nineteen hundred and twelve;

Not seeing the life that has been his dying since,

Though he has braked the crawl toward surcease

More courageously successful than we (even I, the Valley’s Poet)

In our existing.

Now, in the final year of his dying, unfamiliar people,

Like Sadie his long-suffering, gentle wife,

Plunge his hat on his head and speak of things

(Eat your bread, Father, then we’ll help you to the bathroom)

Having nothing to do with the untranslatable essence

Of those Maori days worshipping with savages who loved him,

And the boyhood before it, fishing the river,

Talking with God,

They—Sadie, his son Nathan, his granddaughters (two)—

Occupants and masters of his home now,

Caution him, watch your step, Father,

Sit down, shut up the girls are studying,

Try not to cry, Father, sleep well, Father,

We know what’s best for you,

Hushing his twanging outbreaks of Maori war and wedding chants,

The sharp-syllabled cries likely to disturb or frighten

The granddaughters, who must study and listen to

The Beatles.

(: Well, what are they doing here anyhow? This is my house)

(: Shhhh, Father, you’re not well . . . behave yourself . . .

You wouldn’t want us to take you to Blackfoot would you?)

At which mention of Idaho’s mental institution

He cries,

Crumbling the bread on the oilcloth,

Sipping water (perhaps in remembrance of his blood?)

And wipes his nose with a middle finger large

With arthritis, its joint broken by a kicking hog,

Thirty years ago, in the middle of the dying time;

Now guiding that finger to grasp at crumbs,

(Surely, the Poet thinks, in remembrance of the Lord).

Sadie saying: now Father . . .

Gently washes his hands with a washrag

: Your friend is here, you haven’t

Seen him since he went away.

But he cries still, his head bobbing to table’s edge,

His hand uncaring loose

In the kindly grasp of his long-suffering

Who endured and never blamed him for their children’s rags

Throughout the carefree, dying years.

: Father! Don’t you remember?

Carl’s son . . . he’s coming to see you.

He turns his milky eyes up, his lips form, break,

And re-form angles over the cavern of mouth

: Carl’s Boy?

?. . . ?

Yes, yes .. .

For the Poet heard and saw the Maori world,

As a village boy listened and seemed

To understand

The war and wedding chants:

Saw empathetically, visions and remembrances,

As they were—

Of young Mormon missionary, Matthew Daniels,

Baptizing natives in fish-filled streams,

Eating ceremonial trout,

Tempted by but not submitting to barebreasted daughters

Of the chief

Because of Judith, his village sweetheart,

In the days of living when vows were not mired

In the moss of lust.

Saw too, himself pleading for more tales,

More songs, more images of rivers and oceans

Aborigines paint-smeared and loin-cloth

Naked—

Saw too the young Matthew equally vermillion and naked,

Dancing chanting with them,

Like one of them —

Saw too his leading the chief

Into the river,

Baptizing him in the name of God, Son, and Holy Ghost,

Not insisting as all missionaries were ordered

That the otherwise pure in heart

Must discontinue smoking pipes—

Seeing Matthew smoking with the chief,

Minutes before and minutes after

The dunking ceremony

(: I tried to do right. I tried!)

(: Now, Father, hush, we’re here)

: Carl’s son,

And his arm goes out, recognizing.

: Brother Daniels, I’ve come to take you for a drive . . .

To the river,

The long-suffering jams his hat on his head

: Father, you hear that? He wants to take you

To the river? Won’t that be nice?

But he has been searching not her words,

Nor the poet, but

A remembrance;

The milky intensely blue eyes frown,

Then see the memory.

: You asked me,

The memory asserts authority now,

:How could you know, and I told you I don’t know . . .

It’s different for every man.

His eyes dance now with the days of two decades ago,

When the boy often touched the time of the old man’s living;

When those in the village thought him only pleasantly eccentric,

And blamed him affectionately for being improvident

To his now well-employed children

The saints milked his cows,

Cut his hay,

Stacked it,

While his carefreeness mocked

Their industry and sweat,

With Maori songs; and along the river

He trapped in constant dialogue with elusive fish;

The Saints of Zion loving him full well,

Unconsciously asking him the light and the way,

Envying him, clucking tongues forgivingly

Over the frightfulness of such sloth that dared

Comb abnegation through the beehive of their Mormondom;

Yet innerly knowing he knew secretly

Grandeurs of heaven and earth they

Could only pretend to know

While they righteously worked their days

Honestly

Paid tithes

Honestly

Churched themselves

Honestly

Uttered Sunday platitudes

Honestly

And strove for honest tractors, electricity,

And plumbing, and education;

Acquisitions, all, he never argued with,

But preferred to fish into the cyclic nonsense they are,

Than have.

: It was one day I was hauling straw for your father, down from

Maple field. It was cold that day,

And you were just about knee high to a grasshopper.

Ignoring Sadie’s hand, urging him to rise,

To go,

:And you said : I don’t know, Brother Daniels,

How does a body go about knowing? And I didn’t

Tell you like some others do, to pray and read

The Book of Mormon.

His voice rising, justifying his own form of

Honesty,

His milky intensely blue eyes straining,

Frowning into the Poet’s face who

Is remembering that he too was blooded into the village

Life, then.

: Because it’s different for every man,

And sometimes when you want to know, you can’t,

You can’t!

That’s all there is to it!

He trembles as if

The powerful unseens of orthodox voices

Are claiming otherwise.

: Shhhh, Father . . . now here’s your coat. . .

Don’t keep him waiting.

: You can’t!

Unaware of the coat she has draped over his arm,

Of the Poet’s hand guiding him out of the chair,

Of long-suffering holding the door open.

: It’s different. . . there’s no telling . . .

And the Poet knows there is no telling . . . anything,

For that is why he is back to the old fisherman,

To learn to know, then to tell,

From the spirit of his old and first teacher,

In the glowing dying days;

In hay rack days.

: His arthritis is so bad,

Long-suffering’s voice a sadness,

A story and a poem

She of patience and no complaints,

Whom no woman in the village ever envied;

She, waiting, knitting the two three four nights

Of his fishing absences,

His announced planlessness

While the hay burned and the unmilked cows

Broke half the fences in town.

: Arthritis this, arthritis that!

Mumbling, staggering,

Critical in his brief return to the world of his long-suffering’s

Pitiful narrow-worldness,

She, never having had a vision on a hillside

Or anywhere else,

Never feeling wildly certain of anything

Except a loaf of bread,

A knitted sock.

: The sun was bright as a gold piece,

He says, his joints testing the pathway uncertainly,

: But it was cold that day .. . I tell you . . .

It was awful cold that day . . . and me with a fever

Like a bonfire.

His broken finger joint fumbling over his lips,

He limps and stops, repeating it was different for every man,

But the way he first knew was the night

He lay in a thicket on a New Zealand hillside,

Sick and feverish when

Lo and behold

God and Joseph Smith appeared in a bath of light

: I saw them,

He, nearly screaming,

Eyes and lips weeping.

From the porch: Now, Father . . . don’t . . . please don’t. . .

He turns, walks a jerked speed,

Lips angry now,

Eyes intensely blue searching the gravel path.

: She don’t know

They think I’m two shades in the wind;

But they don’t know . . . my own house!

But the poet busily deafens the traffic of sadness,

With noises of memory—the sleigh ride day, the load of straw

Among the many loads from maple field,

The snow crusty in the isinglass fields,

Hard and glistening beneath the runners of the long lane roads;

He and the old fisherman buried for warmth in the straw,

Noses dripping and feet yelling numbness,

In the days of dying

When animals seemed the lucky ones,

Fed and warm when humans sometimes weren’t:

And the Poet sees the horses foaming in the traces

Snorting and defecating,

Their hooves crunching the hardpacked snow;

And remembering the old fisherman’s telling again

Of God and Joseph Smith laying hands upon his fevered head,

Commending him for his faithfulness

In rejecting the chief’s request to cohabit

With two of his unmarried daughters,

Hence to plant the seed of Israel in his royal blood;

Then the two personages, glowing brightly as a gold piece,

Commanded the fever from his body,

Bade him rise from the hillside —

: Go forth

And do a mighty work

Among a needful, heathen people;

And if thou are faithful it shall come to pass . . .

But neither in the living nor in the dying years

Did the personages finish their prophecy upon his head,

Leaving him to ask five decades of fishes for the means of his

Salvation.

: I tried,

Limping, clutching the Poet’s arm,

: I tried . . . to do my best.

Small compensation since nineteen hundred and twelve

Talking to a river about what living was like,

Convincing elusive fishes of the agony

Of whistling into the graveyard of the villagers’ ears

All that they could not know

Of his great knowing . . .

The Poet drives slowly beneath, then into,

The foothills of Pescadero

Seeing a yellow grove of aspens where,

Before his time, a bishop’s son

Slew himself herding his father’s sheep;

Not listening to the Gabble of where,

In countless fishing holes, the old fisherman

Sought answers to his fate

From fishes.

From hooks to lines to bait to water battles won and lost,

He gabbles.

Finally to Judith, his long-waiting sweetheart,

For whose gospel sake he spurned the barebosomed Maori maids,

He talks;

Of having married her in nineteen hundred and twelve,

Honeymooning at the quarterly gathering of Zion’s flock

In Salt Lake City,

There seeing Brother Murdock his New Zealand

Mission President who said,

: Matthew, are you still fishing . . . good! . . .

Hugging the intense villager who

Converted more Maoris than all missionaries combined.

: So busy with real estate and church, I gave it up . . .

Don’t let any get away! . . .

. . . But don’t forget to love the Lord!

: He was a good man, President Murdock,

Never a better one ever lived.

Crying now, softly,

The big finger crossing under his nose;

For the day after, Judith took sick,

Dying in Salt Lake of appendicitis

Under the prayers of Murdock imploring the Lord

To spare her,

: I come home and started going with Sadie,

He said. But broke off.

: I don’t know why I’m a-talking like this,

His eyes coming back with re-interest

As he sees a certain bend in the river,

Beneath Pascadero,

And his spirit lights with memory of a big one,

Landed in Hoover’s time,

The very day? (the Poet ponders)

When he, the village constable, forgot to open the polls,

Was off fishing, and the saints had to hoist

A boy through the schoolhouse window.

: Nathan helped me pull him out. . .

Must of weighed six pounds!

Then the narrative of his beginnings,

Flowing as coherently and true as hayrack conversations

In the days of dying—

His father, a trapper named Billings;

Mother a half-breed Indian;

The child orphaned

(: I dunno if they left me or died or what)

And cared for by his mother’s people,

Known of, somehow, by the Poet’s grandmother who,

Also knowing of Old Gus and Hilda Daniels’

Long childlessness, took him

From the burdened grandparents,

And transported him in a boxwagon

To Bear Lake Valley, keeping him

Alive on mare’s milk during the long and delayed journey

From Fort Hall.

Indulged by his foster parents into an idlyllic

River-fishing childhood, permitting him to determine

When or whether to go to school,

And leaving him with reasonable property and money

(As village legacies go) which he used

To perform his three year mission,

Then mismanaged and squandered through neglect

From nineteen hundred and twelve unto this day,

Preferring now, as eight decades ago, to fish

The river every day that the obstructive theys

Will let him,

Crying when they will not.

And through all the days of his dying

Always refusing the complications of family-rearing,

Plying the river for completion of the personages’ promises;

But not knowing, the Poet thinks, that he was

Becoming a twentieth-century impossibility,

A wonder of the world that couldn’t be,

But was;

Daily returning to the river to secure simplicity;

And though too kind to refuse office and task—

Constable, sexton, gravedigger, butcher—

Too near the magic of idyl to often perform them,

Paying the Saints the inconvenience of his unmilked cows

With messes of fish, and to the bishop too

His tithing—one fish in ten to the Lord.

In the car bumping through pioneer logging trails

Weeded over now, he speaks of recent reform,

Enforced by arthritis and winters too long.

: Been going to church,

He says, like a child learning to swim again.

: Going back now I’m old. But they think I’m

Two shades in the wind and . . .

Choking, bringing the broken joint to his nose,

. . . : They made me sit down . . . I was telling them

How I came to know . . . fever like a bonfire . . .

Wasn’t half through and the bishop told Sadie to make me

Quit.

Because (the Poet thinks) he is the conscience of the village—

The Saints could not bear the chilling pierce of the Maori songs

Cracking the walls of the churchhouse and reminding those

Who have become old with him, that this is his dying year;

Or perhaps, because he announced the chant

As picturing dying suns, they felt

Premonitions of their own Yorick time.

I, the Valley’s Poet, stop the machine

That I have accepted as consonant with my century,

And walk in the yellow aspen grove

Where the boy slew himself before my time,

Seeing in the eye of my soul

The Pescadero hills,

The stubble fields, reaped,

And the river, faint and long, below;

Tormenting myself not of dying

But of living in a rocket century.

Knowing the arthritically old man

Trembling in the car

In the final sign of sanity

In this the final year of his dying;

Knowing the how can anyone know”?

Of our hayrack day gliding over isinglass snow

In maple field is no answer other than

The one he gave, and persisted in.

And now I long for his

Gift of leaving

A way and a time so rich;

To do as he has done;

To be as he has become.

Leaving a river for others to find

For more than they know will be.

Yet who can give such offerings as he,

At the water’s edge,

Or offer the gift of self unto its flow?

Who? For eight decades unremitting?

Only he, whose mystery is to be reclaimed in that same innocence

From which, orphaned, he began.

The car starts, moves downhill,

Stung by the lashings of dead willow limbs.

: Be careful, Brother Daniels,

Of the river.

: Tumble in?

Mischief streaking the milky intensely blue eyes,

: O, I ‘spect so . . . someday . . . this winter . . . maybe.

Caring not;

For he tried to do right in the days of his living,

Knowing he saw them one rainy night —

God and Joseph Smith.

: I saw them again the other night . . .

Funny thing, they looked a little

Like Judith,

Chuckling, gazing, now pointing the crooked finger to

A certain bend where

He and Nathan pulled a big one

Into shore.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue