Articles/Essays – Volume 55, No. 1

The Divine Feminine in Mormon Art

For the first century of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, members generally did not condone artistic renderings of deity, including those of Christ.[1] It was not until the mid-twentieth century that Mormon artists shifted toward portraying God, and even then did so in fairly limited ways. Laura Paulsen Howe, art curator for the Church History Museum, describes the Church’s embrace of images of Jesus as “a big cultural shift.”[2] When they did appear, Church-approved images of Christ and Heavenly Father skewed heavily toward depicting white, European-looking men in an illustrative style. In May 2020, the Church announced that meetinghouse foyers ought to display only paintings of Jesus Christ and offered a list of twenty-two approved paintings for this purpose, all of which featured Jesus Christ in this style.[3][4] This version of Jesus—tall, white, and bearded—is one well-known to modern viewers and widely identifiable within European art traditions. At its highest levels, the LDS Church has adopted this relatively stagnant and narrow depiction of God.

If images of Heavenly Father and Jesus within Mormon art are a relatively recent and stable development, images of Heavenly Mother are cutting-edge and creative. The sudden increase in art about the divine feminine is far more varied and diverse in its conception of deity. Although lacking official approval, Mormon artists have created numerous images of Heavenly Mother since 2012. Before then, images of Heavenly Mother were almost nonexistent.[5] In 2014, the art contest A Mother Here called for submissions of art and poetry on the subject of Heavenly Mother.[6] In 2019, authors McArthur Krishna and Bethany Brady Spalding published A Girl’s Guide to Heavenly Mother, which included dozens of images of Heavenly Mother by Mormon artists around the world. Professional and amateur artists on social media platforms have shared thousands of images of Heavenly Mother in just a few years.[7]

If “religion is a projection of human ideals,” as scholar Taylor Petrey has argued,[8] then much of Mormon art depicting God tells a story of the primacy of white masculinity. However, images of Heavenly Mother are expanding and may eventually present a challenge to this primacy. It is important to consider this expansion of the images of female deity in light of another concern Petrey has articulated: that the doctrine of Heavenly Mother may be used to further solidify a highly gendered, heteronormative divinity that can be weaponized against people who are transgender, queer, single, or otherwise nonconforming to a male/female pairing.[9] The concern is that by focusing so heavily on gender, “Mormon feminist liberation and empowerment of Heavenly Mother has often shackled her with a new set of discursive constraints” of heteronormativity and reductive femininity.[10]

The search for the divine feminine in Mormon art has resulted in more diversity in conceptions of Mormon deity than have ever existed before. If, as Petrey argues, the threat of a theology of Heavenly Mother stems from “collaps[ing] the difference of women into a singular representation,”[11] art has already begun to offer a very different response. A broad desire for the divine feminine has prompted individual artists to see her in countless diverse ways. Petrey’s wish for a “multiplicity of interpretations without a claim to completeness or supremacy”[12] is a work already begun.

This paper examines sixteen pieces of artwork produced since 2014 by male and female artists around the world who have taken up the challenge to represent a divine female. The collective body of recent LDS art about Heavenly Mother reflects speculative and sometimes uncorrelated theology about her roles and responsibilities in the universe. While many images demonstrate an emphasis on ideas of her maternity, a large portion instead explores her power and authority. The collective body of art about Heavenly Mother inherently retains an interest in gender but also brings to the fore race, body type, symbols and types of power, responsibilities, and other intersections of identity. An exploration of the divine feminine need not come at the expense of gender minorities and other marginalized populations, and this particular moment in history offers an opportunity for radical creativity in artistic conceptions of Heavenly Mother. A multiplicity of the divine feminine can simultaneously give seekers the liberating theology they need while also celebrating the diversity of the human experience. It offers an opportunity for even greater “imaginative theology,” a term scholar Barbara Newman uses to describe the process of using art and literature to deepen perceptions of the divine.[13]

Finally, this paper presents a comparative historical context of the two divine feminine figures of Heavenly Mother and Mary as an explanation for why the diversity of art depicting Heavenly Mother exists. Heavenly Mother artwork echoes many of the artistic tropes of the Virgin, but the similarities have deeper significance. Both traditions provide a varied multiplicity of images of the divine feminine that exceed one limited category. Early art representing Mary was unauthorized by the upper echelons of Christian leadership, just as art representing Heavenly Mother has been largely created by those marginalized within the LDS Church today. The glorification of Mary and Heavenly Mother are both propelled primarily by women within their religious traditions: women with faith but no institutional power.

Mormonism is a vernacular religion, or a “religion as it is lived: as human beings encounter, understand, interpret, and practice it.”[14] Vernacular religion offers an opportunity for believers to use their art, poetry, and literature to engage in their faith. In the case of Heavenly Mother art, this presents the potential for a conceptual framework of deity capacious enough for the diversity of God’s children.

Maternal Deity

Nineteenth-century Mormonism embraced the doctrine of Heavenly Mother and produced the Heavenly Mother poetry of Eliza R. Snow and W. W. Phelps. Speech about Heavenly Mother continued into the early twentieth century. Statements such as the First Presidency’s 1909 declaration that “the universal Father and Mother” are “literally” the parents of all humankind were not uncommon at the time.[15] Yet by the mid-twentieth century, when Mormon artists first began creating portraits of God the Father and Jesus Christ, mentions of Heavenly Mother had become rare. Between 1930 and 1970, LDS general conference addresses included only one reference to a “Mother in Heaven.”[16] While no official explanation for the Church’s shift away from Heavenly Mother exists, many scholars attribute it to the Church leadership’s desire to make the faith more mainstream and accepted within American Christianity.[17]

Although many signs point to the current leadership’s continued interest in conforming to Christian orthodoxy, recent leaders have apparently decided that Heavenly Mother was one doctrine worth rehabilitating from the unconventional period of early Mormonism. Between 2010 and 2019, general conference talks referenced Heavenly Mother fifty-seven times,[18] a notable change from the period from 1930 to 1970. Simultaneous to this renewed discussion at the highest levels of Mormonism, the general membership of the Church has also increasingly become interested in Heavenly Mother. Clearly, while the Heavenly Mother doctrine remains somewhat undefined, her place in modern Mormonism is increasingly visible. Art has been a key element of the expression of this interest. Poetry brought her into the consciousness of the nineteenth-century Mormons, and now poets and artists have led the way for twenty-first-century Mormons. This period of transitional theology has led to a burst of creativity and a diversity of depictions of her.

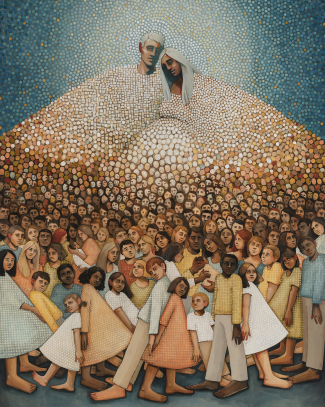

One dominant trend in the new art about Heavenly Mother has been to emphasize maternal roles and imagery. Perhaps the most well-known image reflecting this domesticated theology is Utah artist Caitlin Connolly’s In Their Image (fig. 1). Originally created as the cover for the children’s book Our Heavenly Family, Our Earthly Families,[19] Connolly’s piece encapsulates the modern Mormon inclination to see eternity as a more celestial variant of today’s nuclear families. Composed somewhat like a family photograph, Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother stand together affectionately, sharing a moment of intimacy while surveying their children. As intended, the viewer makes a direct connection between the parents they typically see in a Mormon church pew and our heavenly parents.

Figure 1: “In Their Image,” 130″ × 103″, by Caitlin Connolly, 2017

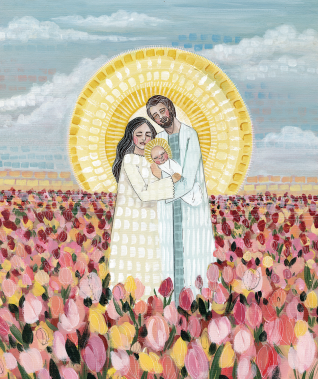

Like In Their Image, contemporary Utah artist Amber Eldredge’s painting Heavenly Parents, Heavenly Child (fig. 2) builds a composition of a mother, father, and child. In this case, only one child is shown—with an individual halo, suggesting baby Jesus—but the surrounding field of tulips suggest multitudes. This image draws on the iconography of the Holy Family, with Mary and Joseph standing and looking down on an infant Jesus, surrounded by divine light. Eldredge specifically describes her version of Heavenly Mother as a template for earthly mothers: “Perhaps our Mother sang, as she rocked us back and forth. They breathed in our pureness and whispered in our ear: ‘You have so many beautiful things to do on Earth, my child.’”[20] This image expresses God as an ideal mother, making snuggling and singing to an infant a divine act.

Figure 2: “Heavenly Parents, Heavenly Child,” 16″ × 20″, 2019, acrylic and ink, by Amber Eldredge, 2019

Modern Mormons have an affinity for images of God as part of a nuclear family. There is something surprising about this for those familiar with Mormon history, especially its earlier embrace of polygamy and open kinship practices. As scholar Samuel Brown has written, Joseph Smith’s “Mormon heaven was emphatically not the Victorian hearth of the increasingly popular domestic heaven.”[21] In contrast, Mormons of today seem to imagine heaven as a shinier version of their current wards: a collection of families, with heavenly parents teaching, playing, and working with their endless spirit children. David L. Paulsen and Martin Pulido note that some Mormon scholars “lament that Latter-day Saints usually acknowledge [Heavenly Mother’s] existence only, without delving further into her character or roles, or portray her as merely a silent, Victorian-type housewife valued only for her ability to reproduce.”[22] They continue: “Perhaps the most accepted and easily understood role of Heavenly Mother is her role as procreator and parent.”[23]

These domestic depictions of the divine feminine are not unique to Mormonism. As noted previously, the history of art portraying a mother and child is widespread in Christian and non-Christian contexts. European Catholic artists “derived a great deal of pleasure from placing Mary within domestic settings.”[24] So, too, do Mormon artists today find comfort and inspiration in deifying motherhood. For many, pairing deity with images of home life feels like the sanctuary they need in a dark world. This may be a similar desire to that of mainstream Christianity described by medieval art historian Miri Rubin as “yearnings for Mary echo that loss, the nostalgia for the sounds of childhood, the warmth of kindred bodies, for the incomparable acceptance of the maternal embrace.”[25] The divine feminine as a perfect, divine parent reflects an idealized, impossible version of family life, but one that people around the world have clung to for millennia.

Christian artists have historically signaled deity through giving God the tokens and items of local political power.[26] What are the signs of power for modern Mormons? In a religion dominated by teachings about the heteronormative family, it makes sense that divinity would be denoted through parenthood. Thus, images of deity as parents do not only reflect how our faith interprets the role and purpose of God—they also signal to the viewer God’s power and nobility.

Cosmic Creator

The “cosmic creator” category of LDS art includes images in which the divine feminine is situated as an author and manager of the universe. These paintings frequently include stars or other astronomical signs that point to her power. Within this category are images that partner Heavenly Mother with Heavenly Father as well as those in which she stands alone, a goddess in her own right. The Mormon art depicting Heavenly Mother as a cosmic creator draws on works depicting the assumption of Virgin Mary. These works portray Mary as “a partner of Christ,” working in tandem with him throughout his ministry. She is “an agent” unto herself, important not just for her maternal role but for her spiritual power.[27]

Utah artist J. Kirk Richards’s painting God Made Two Great Lights (fig. 3) from his series After Our Likeness is an example of the astronomical setting for Heavenly Mother. This series of more than a dozen paintings follows the first two chapters of the book of Genesis and features multiple images of heavenly parents creating the world together. The two gods work in partnership, blowing life into their creations and rejoicing at what they have made. While each figure is clearly identifiable as male or female, their roles are not gendered in any way.

Figure 3: “God Made Two Great Lights,” 10″ × 20″, oil on panel, by J. Kirk Richards, 2017

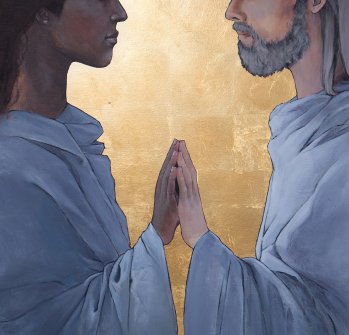

Although no stars or planets appear in Canadian artist Heather Ruttan’s Equal in Might and Glory (fig. 4), I place her image in this loose category as well. This illustration is significant in the way it demonstrates Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother as precisely equal: they are the same height, wear the same clothing, and each takes up exactly half of the image. This piece also deserves attention for depicting heavenly parents as a mixed-race couple, taking one step in filling a yawning void in Mormon images of deity.

Figure 4: “Equal in Might and Glory,” 30″ × 30″, acrylic and gold foil on canvas, by Heather Ruttan, 2019

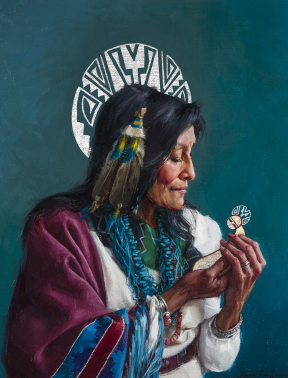

Of paintings of Heavenly Mother featured alone and as a creator, Santa Clara Pueblo Indian artist Kwani Povi Winder’s Welcome Home (fig. 5) stands out as particularly compelling. Like other Christian artists, Winder depicts deity with the tokens of power belonging to her own culture: Heavenly Mother, modeled after the artist’s mother, wears the robe, headdress, and jewelry of a Pueblo Indian. The angles, circles, and swirls of her halo are a mix of Pueblo and LDS temple symbolism.[28] In doing so, Winder not only questions the typical Mormon assumptions about the race and gender of God but also pushes back on traditional notions of what signifies power. Rather than a priestly hat or kingly robe, objects associated with the most authoritative figures in certain societies, she uses items belonging to a group of people who have been disenfranchised and systematically marginalized. The effect of reclaiming these symbols is to insist on power that defies patriarchal limitations and sources in favor of the power of Indigenous ancestry and female family connections.

Figure 5: “Welcome Home,” 16″ × 14″, oil and metal leaf on linen panel, by Kwani Povi Winder, 2019

This kind of respect for a divine feminine as creator and guide is also found within Mormon teachings of Heavenly Mother. The Women of Mormondom, edited by Eliza R. Snow, “affirms that the ‘eternal Mother [is] the partner with the Father in the creation of worlds.’”[29] Charlotte Shurtz has found that modern Mormon women hold similar beliefs today; her interviews with Mormon women about Heavenly Mother revealed an almost universal belief that Heavenly Mother helped create the world.[30]

Ineffable Divinity

Despite Mormonism’s traditional reliance on realistic illustration, a growing number of artists are exploring Heavenly Mother through non-representational art that uses symbols to convey a concept or entity. Perhaps drawing on the long-standing struggle to adequately depict deity in a single human figure, these artists’ use of shapes and symbols invoke a limitless divinity. They offer a potential future in which God transcends the social constructs that typically undergird Mormon artistic renderings of the divine.

London-based American artist Lisa DeLong’s The Key of Knowledge (fig. 6) is one of the most extraordinary examples of this type of religious art. DeLong’s art, which exclusively uses geometric shapes and patterns, is more reminiscent of traditional Islamic art than European Christian art. The repeating and interlocking circles, set against a swirl of motion that mimics the wood grain of a tree, subtly references traditional symbols of the female divine without settling on one way of depicting her.[31] The viewer can interpret the image in any way she chooses, which gives space to question just how relatable and human an unknowable deity could be.

Figure 6: “The Key of Knowledge,” 22″ × 33″, gold leaf, watercolor, gouache, and ink on handmade marbled paper, by Lisa DeLong, 2019

American software engineer and digital artist Ben Crowder has also done a series of works about heavenly parents that embraces abstraction. In Their Work and Their Glory (fig. 7), he references the idea of two separate beings in partnership through an image of two triangles—one with the point up and one with the point down—fitted together to form a parallelogram. Unlike most other Mormon art images, the beings in Their Work and Their Glory are un-gendered and unidentifiable. Though together they form a unified shape, they each maintain their own separate individuality.

Figure 7: “Their Work and Their Glory,” digital, by Ben Crowder, 2020

By producing work in which Heavenly Mother is represented through symbols, artists like Lisa DeLong and Ben Crowder as well as Paige Crosland Anderson, McArthur Krishna, Claire Tollstrup, Katrina Berg, and Katie Payne allow the viewer to imagine her with or without social constructions. These are perhaps the most radical works on deity in all of Mormon art and highly unusual in a faith that has traditionally embraced realism and illustration.

Diversity in Collectivity

Many artists are eagerly constructing an artistic intersectional analysis of Heavenly Mother. Artists such as Melissa Tshikamba, Michelle Franzoni Thorley, J. Kirk Richards, Esther Hi’ilani Candari, Michelle Gessell, Kwani Povi Winder, Amber Lee Weiss, Heather Ruttan, and Arawn Billings have painted Heavenly Mother as Black, Latina, Polynesian, Asian, Native American, and other races and ethnicities.[32] The racial diversity of images of Heavenly Mother is far greater than for Mormon images of Heavenly Father. Without commotion, Mormon artists have started an intersectional feminist theological revolution: in a space where God has consistently been portrayed as a white man, they have offered numerous images of God as a woman of color. Evidence of the institutional Church’s growing acceptance of this kind of Heavenly Mother art is the decision of Brigham Young University, the LDS Church History Museum, and the Church-owned bookstore Deseret Book to carry A Girl’s Guide to Heavenly Mother, which includes many racially diverse images of a divine feminine.

Canadian artist Melissa Tshikamba’s Breath of Life (fig. 8) stands out as an example of the artist’s devotion to a Black female goddess, one whose power is intrinsic to life on earth. “Many of my paintings incorporate spiritual symbolism and people of color to give solace to those who don’t see themselves reflected in spiritual art,” Tshikamba has written.[33] In this painting, the golden halo of divinity is echoed in the gold earring, a reminder of how Heavenly Mother is both universally omniscient and personally known to an individual. Tshikamba explains, “I often depict gold or circles in my artwork, which to me are symbolic of divinity, royalty, and nature.”[34] Tshikamba has combined her interest in race and gender to produce a feminine divine that appeals to the intersections of her identity.

Figure 8: “Breath of Life,” 11″ × 15″, watercolor ink and gold leaf on paper, by Melissa Tshikamba, 2020

In the collage piece Romana (fig. 9), Amber Lee Weiss uses her Native American family history as a direct template for a divine mother. Along with wings made of flowers and a halo made from a clock, Weiss gives her Heavenly Mother the face of her own great-grandmother, who, Weiss writes, “was a mother to all.”[35] In making this art, Weiss took the doctrine of Heavenly Mother and personalized it to her own family, her ancestry, and her ethnicity.

Figure 9: “Romana,” 9″ × 9″, hand-cut collage, by Amber Lee Weiss, 2019

Besides racial and ethnic diversity, artists depicting Heavenly Mother have chosen a variety of ages. Mormon images of God the Father and Jesus typically depict a generational age difference, with both figures between the ages of approximately forty to sixty-five. To my knowledge, there are no Mormon images of Heavenly Father below the age of approximately fifty, as artists have generally accepted the tradition of depicting him in the role of a father to an adult man. In contrast, images of Heavenly Mother are flexible about her age. In Romana (fig. 9), the divine feminine appears approximately in her sixties, while Melissa Tshikamba’s Breath of Life (fig. 8) goddess is likely in her twenties or early thirties. Heather Ruttan has portrayed her multiple times as an elderly woman, while Jenedy Paige’s interpretation in Mother (fig. 10) places her as a very young woman, possibly younger than twenty.

Figure 10: “Mother,” 18″ × 36″, oil on canvas, by Jenedy Paige, 2019

Artistic representations of the divine feminine are also adopting a variety of body types to represent diversity. Some Mormon artists have portrayed Heavenly Mother as strikingly tall and thin, such as in Courtney Vander Veur Matz’s Mother Divine or Eliza Crofts’s Sophia. Body type is impossible to analyze in Romana (fig. 9) and Breath of Life (fig. 8)—the former because the medium of collage obscures the body and the latter because it is a bust. However, the general observable trend is toward a median body type, such as in Cambodian artist Sopheap Nhem’s Heavenly Mother (fig. 11) or Kwani Povi Winder’s Welcome Home (fig. 5). Possibly because of the constructed role of motherhood, she is occasionally given a soft postpartum belly and round hips, such as in Jenedy Paige’s Mother (fig. 10). This body type reinforces her maternal identity.

Figure 11: “Heavenly Mother,” 34″ × 30″, oil on canvas, by Sopheap Nhem, 2015

Only a few artists have ventured images of a fat or plump deity, including Heather Ruttan and Michelle Franzoni Thorley. In her untitled Instagram post from April 27, 2020 (fig. 12), Ruttan overtly ties this divine feminine to the body positivity movement, giving further evidence of the ways in which images of Heavenly Mother empower women. She wrote on the post, “Here is my little attempt to celebrate bodies that change without permission, they are still precious and irreplaceable.”[36] Franzoni Thorley expressed similar thoughts in an explanation of her piece Diosa (fig. 13). “The images that existed of her were always of a very slender woman. That’s when I began to think ‘What if she has full round hips and tummy?’ And so you see her here full and round because big bodies are divine bodies too.”[37] This area of body diversity deserves greater exploration from Mormon artists, but again, existing images of Heavenly Mother are more diverse in this category than those of Heavenly Father, who consistently appears tall and fit.

Figure 12: “Untitled,” digital, by Heather Ruttan, 2020

Figure 13: “Diosa,” 26″ × 22″, oil on canvas, by Michelle Franzoni Thorley, 2019

Besides the body of the divine feminine, landscape is another way of representing diversity. Mormon artists from around the world have created work on Heavenly Mother, frequently placing her in localized surroundings or with items and symbols familiar to their native culture. Artists such as Sopheap Nhem (Cambodia), Joumana Borderie (Lebanon/France), Richard Lasisi Olagunju (Nigeria), Louise Parker (South Africa), Susana Isabel Silva (Argentina), Haylee Ngaroma Solomon (New Zealand), and Sherron Valeña Crisanto (Philippines/Qatar) have all contributed diverse images to the canon of Heavenly Mother art. The stylistic differences and varied settings offer viewers a way of reimagining deity and breaking down assumptions about the clothing, accessories, and surrounding environment of God. For example, in Heavenly Mother (fig. 11), Nhem depicts a medium-sized, middle-aged southeast Asian woman wearing traditional Cambodian clothing, including a golden skirt, embroidered blouse with gold thread, a gold belt, and a pink and gold scarf wrapped around her shoulders. She also wears a traditional Cambodian tiara, signaling royalty or divinity. In comparison, Olagunju’s Goodly Parents (fig. 14), made of intricate beadwork, includes a border of patterns typically found in West African textiles. Both Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother wear a dashiki, a colorful garment with embroidered collars found across Africa and the African diaspora. Heavenly Mother’s hair appears to be in locks or braids, a powerful symbol for Black women claiming power through natural hair. The twelve pieces of hair represent the twelve tribes of Israel, which is unusual and forceful symbolism for a female figure.[38] The geometric shapes of the bodies are reminiscent of ancient carved figures. In this colorful piece, age is obscured, but the bodies of the masculine and feminine are almost identical in size and height, with the divine feminine figure only slightly thinner. Nhem’s and Olagunju’s versions of Heavenly Mother are radically different in concept, style, and medium. Yet both make bold statements about their ancestral legacy and what is inherently divine.

Figure 14: “Goodly Parents,” 28″ × 40″, coral beads on wood, by Richard Lasisi Olagunju, 2019

The parameters of gender diversity in depictions of Heavenly Mother art have been more flexible than that of Heavenly Father and Jesus. The male deities are depicted as masculine through bodily representation, including the almost universal use of beards. Historical images of the Virgin Mary likewise emphasized her femininity, with long hair, a graceful body, and intense focus on her breasts.[39] In contrast, images of Heavenly Mother frequently do not overtly signal narrow indicators of gender. Her clothes are often loose-fitting, giving no indication of the contours of her breasts, waist, or hips. This can be seen in images such as Romana (fig. 9), Goodly Parents (fig. 14), Equal in Might and Glory (fig. 4), or Annie Poon’s The Scent of Stardust (fig. 15). In contrast, Breath of Life (fig. 8), Diosa (fig. 13), Mother (fig. 10), and Heavenly Mother (fig. 11) are more overtly feminized with the use of long hair, slender features, and/or clothing that emphasizes the breasts, belly, and/or hips.

Figure 15: “Scent of Stardust,” 7″ × 12″ × 1″, fabric, polyfill, and acrylic paint, by Annie Poon, 2019

Self-identifying queer artists including Eliza Crofts and Charlotte Shurtz have offered their own versions of Heavenly Mother. Shurtz describes Heavenly Mother as a “core doctrine” of LDS theology[40] and has written that because “it is impossible to become like someone we don’t know, we must have knowledge of not just God the Father but also God the Mother to gain salvation and exaltation.”[41] Shurtz’s depictions of Heavenly Mother do not include any overt signals of a queer Heavenly Mother, but Shurtz intends for them to be understood that way. “Frida’s Heavenly Mother” (fig. 16), a collage bust of a middle-aged Black woman with a wreath of flowers and white clothing, is “absolutely” a lesbian goddess, according to Shurtz.[42] Asked if it was important that viewers see “Frida’s Heavenly Mother” as queer, Shurtz said, “It matters that we think she could be, that we consider that as a valid option. It’s not just straight people or cisgendered people who have divinity within them. It’s important that we tell a wide variety of narratives about God . . . because those narratives inform us of who is worthy of love.”[43] Shurtz’s artwork is meant to prompt viewers to see a queer identity in the divine, which is part of seeing the divine in a queer identity.

Figure 16: “Frida’s Heavenly Mother,” 11″ × 16″, paper collage, by Charlotte Scholl Shurtz, 2019

These new representations are innovating by adapting Heavenly Mother to twenty-first-century global Mormon contexts. But they also reflect a tension between traditional images that represent her as a “perfect mother,” accompanied by husband and children, and those that are seeking new images of womanhood. As described earlier, modern LDS artists have depicted her in a wide variety of body types, races, and ages. They have also portrayed her as a goddess in her own right, a cosmic creator, and a co-founder of the world. Some artists have nodded to the ineffability of deity, bucking the Mormon tradition of literalism and perhaps inviting a reconsideration of gender dualism. In 2016, Taylor Petrey wrote, “While LDS tradition has a plurality of male characters to resolve the problem of a singular masculinity through multiplicity, perhaps there is no corresponding plurality for female representation in the case of Heavenly Mother.”[44] In the few years since Petrey’s critique, a new realm of Mormon art has countered this claim by offering images of deity that reveal greater multiplicity in gender performance for the divine feminine than for the divine masculine. Images of Heavenly Mother have brought some mild increased diversity in location and aesthetic to images of Heavenly Father through art that pairs the two figures together and challenges typical stylistic norms. Yet depictions of Heavenly Mother are still far more diverse than images of Heavenly Father with regard to age, race, ethnicity, and body type. One reason for this difference is Mormonism has generally adopted a narrow artistic aesthetic regarding God the Father’s appearance.

At the same time, the artistic stretching to depict the divine feminine has had another effect on LDS art in the representation of divine maleness. For LDS artists today imagining how to depict Heavenly Mother, there is no clear art historical precedent to depict her divinity. Images of Heavenly Mother produced in the last five years frequently include Heavenly Father. Artworks such as In Their Image (fig. 1), God Made Two Great Lights (fig. 3), and Equal in Might and Glory (fig. 4) have made waves within Mormon circles for their depictions of Heavenly Mother. But they also break an important, if unofficial, stricture by showing Heavenly Father outside of the Sacred Grove and without Jesus. Artists’ work in the genre of Heavenly Mother has not only broadened the Mormon conception of a divine feminine but also prompted more diverse interpretations of the divine masculine.

Vernacular Religion

As these examples have shown, LDS images of the divine feminine have been freer to invent new ideas by departing from the uniformity of male deities in Christian art history and its LDS branch. How might we explain this? Diversity in Heavenly Mother art is fueled by the unsanctioned nature of the topic as an expression of vernacular religion. This rise in artistic diversity parallels the diverse art representing the Virgin Mary, also a figure of popular religious representation. Miri Rubin’s book Mother of God: A History of the Virgin Mary provides a sweeping study of Mary’s emergence as a powerful religious figure from the earliest years of Christianity through the seventeenth century. Rubin describes how early devotees used art, music, and literature to endow Mary with divine power while also adapting her image to local cultures. The theological and artistic evolution of Christianity’s most significant feminine figure provides an interesting comparison for understanding the development of art about Mormonism’s Heavenly Mother.

For the first thousand years of Christianity, the question of what role Mary ought to play in devotion hung over religious life. Debates about her divinity, her purpose and roles, and her attributes engaged scholars, priests, and lay members. The propriety of venerating a feminine figure was one of the most controversial issues. Mary disrupted traditional male religious power. She was, as Rubin describes, “a mystery of divinity touching earth, an unexpected female intrusion upon the stage of male world power.”[45] In the religious world, a powerful divine feminine figure posed a potential threat to the primacy of masculinity.

Unlike God the Father, Mary seemed approachable and adaptable to a variety of devotees, from laity to monastics and clergy. These devotees saw her as an advocate before a stern deity. Rubin suggests that “Mary’s power in the lives of many Europeans emerged from familiarity and accessibility, not from rarity and distance.”[46] She could inhabit any role that those searching for a female divine wanted: a perfect virgin, perfect mother, Queen of Heaven, and daily companion all in one figure. People—particularly women—felt that Mary understood them, identified with them, and could offer them solace in a way that was more personable than a distant Father God. “In her was to be found a niche for every type of woman: young maiden, chaste widows, hard-pressed housewife, leisured bookish reader, the shy as well as the outgoing, the tongue-tied and the eloquent. In her figure were already engrained the possibilities of silence as well as song, modesty as well as majesty, innocence as well as wisdom. Each and every Christian could find a place in Mary.”[47] Mary’s ability to adapt to a multiplicity of feminine roles and types made her appealing for a wide variety of faithful women.

Mary’s popularity extended to the art world as well, from high art to folk devotion. The most influential early text of Marian fervor, Meditations on the Life of Christ,[48] took the form of a guidebook for religious lay women. Medieval nuns were also devoted to Mary and created dolls, handwork, and paintings to express their faith.[49] As she grew into a global icon, depictions of Mary varied according to the local culture. Images of Mary became part of devotional family life, inspired women religious in convents, and welcomed people to churches and cathedrals. This was truly a broad spectrum of the devoted: men and women, old and young, educated and unlearned, pious and mildly devoted.[50] Europeans of all sorts depicted her as a reflection of themselves.

Mary images not only echoed the diversity of European life, they also adapted to every new nation where Christianity spread. Missionaries and traders carried her with them to all parts of the globe. People from around the world saw Mary in themselves, and therefore saw themselves in Mary. In Ethiopia, artists sometimes gave Mary “elongated oriental eyes,” while in Macao adherents blended her with the Buddhist following of Guanyin. In Japan her image mixed with that of Kannon, a divine feminine figure forbidden by the feudal military government that ruled from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries.[51]

In a broad survey of art history, Mary has been one of the most variable and widely reproduced figures in the history of religious iconography. This should, perhaps, be unsurprising: mother-and-child imagery is one of the most pervasive forms in all of art history. As Rubin notes, “Jesus was a god who had been mothered,” and regions that already had traditions of a female divine in a maternal role easily adapted and adopted Christ and Mary for their own use.[52] But there are other reasons for her popularity. Devotional art of the divine feminine is driven by the desires of the faithful who are outside of traditional patriarchal authority. Mary’s ubiquity and adaptability then went hand in hand, as she came to not only represent a particular biblical character but to provide another path for connecting a whole range of devotees to the divine. The new art portraying Heavenly Mother draws on some of these same themes as an expression of vernacular religion.

Conclusion

Mormon art has for many decades depicted God the Father and Jesus as white, tall, physically fit, and bearded, with Heavenly Father slightly older or close to the same age as Jesus.[53] The Mormon representation of Heavenly Mother as it has emerged in the last decade has differed greatly from this norm. Instead of a single identifiable image, art about Heavenly Mother has, to a great extent, followed the route of medieval European Christian depictions of Mary: adaptable, localized, imaginative, and fluctuating. This is in part because the Mormon adoption of images of deity in temples and chapels coincided with a shift away from the doctrine of Heavenly Mother, resulting in a lack of an official version of her. It also seems to stem from artists’ desires to see her in themselves, a force for expanding the types of images created.

The increase in official and grassroots discussion of Heavenly Mother is welcome to many Mormons, particularly Mormon women. For a group that often feels disenfranchised and powerless, Heavenly Mother offers a hope for relief by providing a template for a future in the eternities. Mormon women of diverse backgrounds and beliefs frequently speak of the importance of Heavenly Mother to their testimonies and sense of self. In a deeply patriarchal world and church, the recognition of a female God opens theological possibilities that otherwise feel unthinkable.

Yet this doctrine also comes with a potential for harm. Criticism of the Heavenly Mother doctrine points out the ways in which she has been used in conjunction with Heavenly Father to promote a heteronormative deity, to the exclusion of queer, trans, childfree, and single people. By reinforcing a strict gender binary, the Heavenly Father/Heavenly Mother pairing imagines a deity that makes claim to offering global representation but actually ignores the multiplicity of lived experiences for human genders. As Petrey has argued, “The exclusive focus on sexual difference as the only difference in the divine—and thus the focus on masculine and feminine characters in theology—runs the risk of re-inscribing dualistic, structuralist hierarchies rather than challenging the gender politics of culture. Mormon feminists’ idealization of women and absolutization of sexual difference have yet to confront in theoretical terms the question of an exclusionary logic within the ideal.”[54] This is particularly problematic if Mormons embrace a strict, narrow version of Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother that prohibits a wide diversity of interpretations. Petrey continues, “The lack of intersectional analysis in Mormon feminist depictions of Heavenly Mother obscures the realities that human beings are not just sexed, but manifest in different ages, races, and sexualities, as well as class and nationality, all of which are mediated culturally and historically on the body.”[55] Without an investment in theological work that addresses the social constructs that typically limit Mormon discussion of deity, any effort to further elevate the doctrine of Heavenly Mother threatens to comfort and inspire only a limited population. The stricter, narrower, and more stable our collective understanding of deity, the fewer people who can see themselves in God.

Recent art has offered a potential solution to this problem. The vernacular quality to Mormonism presents an opportunity for members of the faith to impact theology through what they create and how they engage. At this moment, a window is open for artists and authors to construct Heavenly Mother in abundant multiplicity. The taboo on discussion about her has begun to lift, though a clear theology and concept about her is not yet in place. Without calcified interpretations of a divine feminine, artists are interpreting her in a wide diversity of races, ages, genders, nationalities, body types, and roles. These artists have begun to offer a collection of images that simultaneously reflect the diversity of the human experience while preserving her authority and power. This kind of theological work benefits the entire faith community. The more images of deity that emerge in all different kinds of roles and types, the more we can collectively broaden our ideas of who God is and who has the divine within them. It is my personal hope that artists will even more enthusiastically reimagine deity in all kinds of forms, embracing the expansive God Mormonism deserves.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] Laura Paulsen Howe (LDS Church History Museum Art Curator over Global Acquisitions), discussion with author, Jan. 8, 2021.

[2] Howe, discussion with author, Jan. 8, 2021.

[3] “Art in Meetinghouse Foyers and Entryways to Reflect a Deeper Reverence for Jesus Christ,” Newsroom, May 11, 2020.

[4] The list of approved images has since expanded, with many images added and some removed. Laura Paulsen Howe, email message to author, July 15, 2021.

[5] An exception to this is artist John Hafen’s “O My Father” series from 1908. The series portrayed images to accompany each set of lyrics from the Mormon hymn of that title, which includes a reference to Heavenly Mother. Hafen used his wife and daughter as models for the image depicting the words, “In the heavens are parents single? No; the thought makes reason stare! Truth is reason, truth eternal tells me I’ve a mother there.” This series was published in the August 1976 issue of the Ensign.

[6] “A Mother Here: Heavenly Mother Art and Poetry Contest,” Exponent II, Aug. 8, 2013.

[7] A search for #heavenlymother on Instagram, for example, yields over seven thousand results at the time of writing.

[8] Taylor Petrey, “Rethinking Mormonism’s Heavenly Mother,” Harvard Theological Review 109, no. 3 (2016): 317.

[9] Petrey, “Rethinking Mormonism’s Heavenly Mother,” 319; Blaire Ostler, “Heavenly Mother: The Mother of All Women,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 51, no. 4 (Winter 2018): 171–81.

[10] Petrey, “Rethinking Mormonism’s Heavenly Mother,” 340.

[11] Petrey, “Rethinking Mormonism’s Heavenly Mother,” 320.

[12] Petrey, “Rethinking Mormonism’s Heavenly Mother,” 331.

[13] Barbara Newman, God and the Goddesses: Vision, Poetry, and Belief in the Middle Ages (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 298.

[14] Leonard Norman Primiano, “Vernacular Religion and the Search for Method in Religious Folklife,” Western Folklore 54, no. 1 (1995): 44.

[15] “The Origin of Man,” Improvement Era 13, no. 1, Nov. 1909, 78. Quoted in David L. Paulsen and Martin Pulido, “‘A Mother There’: A Survey of Historical Teachings About Mother in Heaven,” BYU Studies 50, no. 1 (2011): 72.

[16] Charlotte Shurtz, “Heavenly Mother in the Vernacular Religion of Latter-Day Saint Women,” Intermountain West Journal of Religious Studies 10, no. 1 (2019): 37.

[17] Susanna Morrill, “Mormon Women’s Agency and Changing Conceptions of the Mother in Heaven,” in Women and Mormonism: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, edited by Kate Holbrook and Matthew Bowman (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2016).

[18] LDS General Conference Corpus, quoted in Shurtz, “Heavenly Mother,” 38.

[19] McArthur Krishna and Bethany Brady Spalding, Our Heavenly Family, Our Earthly Families (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2016).

[20] Amber Eldredge (@thecoloramber), Instagram, Nov. 4, 2019.

[21] Samuel Brown, “The Early Mormon Chain of Belonging” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 44, no. 1 (2011): 26.

[22] Paulsen and Pulido, “A Mother There,” 75.

[23] Paulsen and Pulido, “A Mother There,” 76.

[24] Miri Rubin, Mother of God: A History of the Virgin Mary (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2009), 358.

[25] Rubin, Mother of God, 363.

[26] “Thus, Italian painters gave God a papal robe and hat; Germans offered the imperial robes of an emperor; while the French God had an exalted kingly crown.” Adolphe Napoléon Didron, Christian Iconography: The History of Christian Art in the Middle Ages, translated by E. J. Millington (London: Henry G. Bohn), 224.

[27] Rubin, Mother of God, 379.

[28] Kwani Povi Winder, discussion with author, Oct. 1, 2021.

[29] Edward W. Tullidge, The Women of Mormondom (New York: Tullidge and Crandall, 1877), quoted in Paulsen and Pulido, “A Mother There,” 80.

[30] Shurtz, “Heavenly Mother,” 41–42.

[31] The tree is an ancient symbol of the goddess Asherah, as described by Daniel Peterson in “Nephi and His Asherah,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 9, no. 2 (2000): 16–26 and 80–81, and by Fiona Givens in “‘The Perfect Union of Man and Woman’: Reclamation and Collaboration in Joseph Smith’s Theology Making,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 49, no. 1 (Spring 2016): 1–26.

[32] In addition to gratitude to the artists involved, I would like to recognize McArthur Krishna and Bethany Brady Spalding for commissioning and encouraging some of these images for their book A Girl’s Guide to Heavenly Mother (Portland, Ore.: D Street Press, 2020).

[33] Melissa T. Kamba, Facebook, Feb. 21, 2020.

[34] “Melissa Tshikamba: Feeling God’s Love By Looking at a Painting,” Exponent II 39, no. 4 (Spring 2020): 15–17.

[35] Amber Lee Weiss (@amberlieves), Instagram, June 14, 2020.

[36] Heather Ruttan (@ettakay.art), Instagram, Apr. 27, 2020.

[37] Franzoni Thorley (@florafamiliar), Instagram, July 29, 2020.

[38] Richard Olagunju, email discussion with author, Nov. 30, 2021.

[39] Rubin, Mother of God, 211.

[40] Charlotte Scholl Shurtz, “Tackling Heavenly Mother Myths: Why She Is a Core Doctrine,” Seeking Heavenly Mother (blog), Nov. 4, 2019.

[41] Charlotte Scholl Shurtz, “Tackling Heavenly Mother Myths: Knowing Her is Essential to Our Salvation and Exaltation,” Seeking Heavenly Mother (blog), Sept. 30, 2019.

[42] Charlotte Scholl Shurtz, discussion with author, Aug. 11, 2021.

[43] Shurtz, discussion with author, Aug. 11, 2021.

[44] Petrey, “Rethinking Mormonism’s Heavenly Mother,” 315–41.

[45] Rubin, Mother of God, 48.

[46] Rubin, Mother of God, 199.

[47] Rubin, Mother of God, 215–16.

[48] Probably written by Franciscan John of Caulibus, c. 1300.

[49] Rubin, Mother of God, 261.

[50] Rubin, Mother of God, 261.

[51] Rubin, Mother of God, 357.

[52] Rubin, Mother of God, 40–42. One excellent example Rubin shares of this pattern is that of Isis, “mother-goddess of procreation, childbirth, and fertility” in ancient Egypt. As Christianity spread through Egypt, traditions about Isis merged with Jewish concepts of wisdom and Christian devotion to a mother God.

[53] A good sampling of work by LDS artists depicting God the Father and Jesus Christ together can be found at “Artistic Interpretations of the First Vision,” Church History.

[54] Petrey, “Rethinking Mormonism’s Heavenly Mother,” 326.

[55] Petrey, “Rethinking Mormonism’s Heavenly Mother,” 332.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue