Articles/Essays – Volume 13, No. 2

The Enduring Significance of the Mormon Trek

When the bishop asked me to speak, I was pleased to accept this opportunity to think about the contemporary relevance of our pioneer heritage. After telling him that I would speak, however, I had doubts about the appropriateness of my doing so. Unlike many of you, I have no pioneer ancestors. My wife has numberous forebears on both sides of her family tree who made the trek to Utah before 1869, and her mother has been a stalwart in the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers for many years, but I can make no such claim. My ancestors who went West were not members of the Church, did not arrive before 1869 and stopped in Wyoming.

On second thought, however, I decided that it might be more important for me to discuss this subject than someone with ancestors who went to Utah. First, I have no personal stake in glorifying those who made the jour ney. I cannot be accused, as John P. Roche said in an essay on the Founding Fathers, of trying to “find ancestors worthy of their descendants.”[1] Second, and more important, with the growth of the Church, those without pioneer ancestors are now—or soon will be—more numerous than those with such a heritage. If the trek to Utah has permanent meaning, it should be relevant to all members of the Church, regardless of their genealogy.

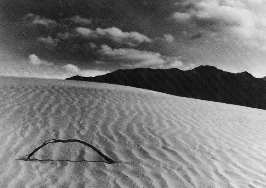

The trek remains among the most powerful and enduring symbols of our ecclesiastical history. The expulsions, persecutions, illegalities and trials suffered during the early history of the Church are considered to have reached their apotheosis in the trek. The covered wagon drawn by a yoke of oxen with its white canvas cover billowing in the wind or the sturdy handcart pulled by the resolute father with a bonneted wife at his side and young children in the cart are among the most emotive symbols of Mormondom. The best known Mormon hymn and the one that strikes the most responsive chord is the great hymn of the trek, “Come, Come Ye Saints.” The founding of the Church on April 6th is remembered, but it is July 24th that is celebrated with fanfare and festivity.

It is in some ways ironic that this event is commemorated as the distinctive holiday of Mormonism. Although great effort and resources were poured into the gathering of the Saints in the Rocky Mountains, within sixty years of the arrival of the first wagon in the Salt Lake Valley, church leaders were already advising members to remain where they were and build up the Church there. The injunction not to gather has been given with increasing frequency over the last eighty years. Why then did the Lord command the Saints to gather? For the gathering was indeed a command, and the righteous were expected to make the trek to Zion just as surely as they were to be baptized.

Today, I would like to share with you my thoughts about why the trek and the gathering are such enduring and important aspects of the Mormon experience.

First, the trek became a key element in the identity of the Church as an institution and in the commitment of its membership. Wallace Stegner, who has written the most readable account, calls it “a rite of passage, the final, devoted, enduring act that brought one into the Kingdom.”[2] It was this shared experience that solidified identification with the Church.

That a journey assumes such a symbolic or practical meaning is not unique; in fact, there are a number of similar experiences in sacred and pro fane history. The Hegira or flight of the prophet Mohammed from Mecca to Medina after years of unsuccessful preaching and persecution marks the major turning point in the success of Islam, and Moslems still number the years from this event. An even closer analogy is the “Long March” of the Chinese Communist Party. After a grueling trek from South China to Yenan Province, during which significant changes were made in leadership, strategy and organization, the party established a remote regional base from which it was later able to emerge united and strong in a successful campaign to dominate China.

Journeys which were important in establishing group identity and are recorded in the scriptures include those of Abraham from Ur to Canaan, the Jaredites from the tower to the New World and Lehi and his family from Jerusalem to the Americas. Perhaps the most relevant similar experience was the journey of the Children of Israel under Moses from Egypt to the land of Israel. Biblical scholars cite the Exodus as the real genesis of Israel’s identity as a people—the key shared experience that welded them into a nation, which even today is an element of Jewish identity.

It is significant that the Mormons saw their trek to the Rocky Mountains as a modern parallel to ancient Israel’s Exodus—they referred to themselves as the Camp of Israel, Brigham Young was compared by Mormons and non-Mormons alike to Moses and great symbolic significance was laid on the fact that the new “Promised Land” had a fresh water lake connected to a saline dead sea with a river that was promptly christened the Jordan. Stegner refers to Jim Bridger’s first meeting with Brigham Young on the little Sandy River in Wyoming in these terms:

The people with whom Bridger spent a long gabby evening were like no people he had ever seen in all his long experience on the frontier. They followed a pillar of fire and a cloud, they went to inhabit Canaan according to the Lord’s promise. . . . Still, in 1847 Bridger had a few years left before the Mormons could multiply and inherit the land, and he had probably not read Exodus recently.[3]

A second consequence of the trek and the gathering in the Mountain West was its importance in further developing group cooperation. This is not to say that mutual assistance was not an important part of the church community’s way of life before 1846; it clearly was. The rigors of the trek, however, re quired a higher degree of mutual cooperation.

A quick comparison of the Mormon and “gentile” migrations indicates how important this was. The Mormons were hardly alone in their move West. Families seeking land and opportunity began to move into the Oregon Terri tory in large numbers at about the same time. The year after the Mormons entered the Valley of the Great Salt Lake, gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill, and the following year the California gold rush was on. The emigrants fol lowed roughly the same route West, but differences in how they traveled were significant. Those who went seeking fortunes in California were principally men concerned with getting themselves there as quickly as possible to harvest quick fortunes. They had no interest in helping others making the same journey, and in fact saw personal advantage in taking all necessary steps to get there first. Even families immigrating to Oregon, although they frequently joined together in wagon trains for protection, generally traveled as individuals.

In contrast, the Mormons migrated as a people. The strong assisted the weak; companies that traveled early in the season planted so that those that came later could harvest. It was a community task to see that every Saint made the journey to the new Zion. The Perpetual Emigration Fund was established to assist European converts without the private means to under take the trip, and during the later years, young men with teams and wagons were sent east from the valleys to bring the year’s emigrants west.

Even after arrival in the Great Basin the necessity for group cooperation was much greater than it was in the Mid-West, California, or any other more hospitable region. Church-organized collective effort was needed to carry out irrigation and establish industries for local development.

This sense of group cooperation is still very much a part of Mormon culture reflected in such things as the Relief Society’s readiness at the first sign of illness to bring in meals and care for young children and the cooperative effort devoted to the building of a new chapel. That this virtue is so much identified with Mormonism today is in part due to our pioneer heritage.

Group cohesion is a third consequence of the trek and the gathering. In sociological terms, a group’s organizational continuity is significantly affected by its capacity to establish and maintain boundaries between itself and its environment—that is, it must maintain a cohesive identity distinct from the rest of the society within which it functions. When an organization first comes into existence this is relatively easily done—the original members of the group are conscious of the reasons for their group’s existence. Over time, however, unless a sufficient level of group identity is maintained, subsequent generations of leaders and members will gradually find the boundaries be tween their organization and society at large weaken and diminish. This is particularly true of a group that adds to its membership large numbers of outsiders.

Two important factors contributing to group cohesion were consequences of the trek and the gathering. First, internal cohesiveness resulted from the shared experiences of the trek and the group cooperation essential for eco nomic well-being. The second factor was external pressure on the Church, which resulted from doubts about the political loyalty of the Mormons. An early manifestation of this problem was President Buchanan’s decision to send U.S. troops to Utah, news of whose coming reached the Salt Lake Valley on the tenth anniversary of the pioneers’ arrival. The conflict with the United States became mixed with the issue of the Church’s right to practice polygamy. Just as the supremacy of the federal government was the real issue over which the Civil War was fought, so also the Church’s conflict with Washington was over the right of the Congress to regulate the territories. And just as slavery influenced and colored the one struggle, polygamy became the specific question upon which the broader Mormon issue was fought. Because of the intense external pressure and conflict, the Church developed an un usually high level of group identity that later permitted rapid growth with little loss of organizational cohesion.

A fourth aspect of the trek is organizational development during this era. The theology and beliefs of the Church were well established by the end of the Nauvoo period, but the organization was not, even though the leading quorums had been organized. The Prophet Joseph Smith was such a dominant figure during his lifetime, and the Church was so small in numbers and so concentrated geographically that it was still relatively simple in organizational terms. Presidencies of stakes had been called in Missouri and Nauvoo, and the evolution of wards began in Nauvoo. The relationship between these two levels of organization and between them and the Quorum of the Twelve, however, was not established until the settlement in Utah. In large part the organizational structure of the Church as we know it today is a product of the gathering in the Mountain West.

The auxiliary organizations are even more directly a product of the west ern experience. I see nods of dissent from the Relief Society sisters. Indeed the Relief Society was organized by the Prophet Joseph Smith in Nauvoo in 1842, but it was disorganized with the exodus from Nauvoo in 1846 and not fully reorganized until the late 1860s. With the coming of the railroad to Utah in 1869, the sisters were called upon to organize themselves into Relief Societies with two goals: encouraging local production of all kinds of consumer products and discouraging the purchase of Eastern goods, which would be cheaper and more readily available with the coming of the railroad. The cultivation of silkworms for production of homemade cloth and the campaign against extravagant Eastern fashions were part of a massive campaign to keep the wealth of the kingdom in the West.

At this same time, the younger women were organized into the Young Ladies Cooperative Retrenchment Society (forerunner of the Young Women’s MIA) to encourage similar virtues among the unmarried. Another aim was to strengthen them against the wicked attractions of the world made more available with the coming of mining. The Young Men’s and Sunday School programs likewise evolved during this period.

The final aspect that I would like to mention is that the trek and the gathering created a regional base for the Church. Indeed, some sociologists consider this to be an important factor in the Church’s survival in its present form. In many areas of the Great Basin, the Church became the dominant social institution, a condition that probably would not have developed—at least to the degree that it did—had the Church remained in the Mid-West or gone to a more inviting place.

Under these circumstances the Church was better able to “socialize” the second generation. In order to perpetuate itself, an institution must success fully retain the allegiance of those who, in Mormon terminology, are “born in the Church.” To do this, succeeding generations must accept the values, beliefs, norms and goals of the organization. As the dominant social institution in the Mountain West, the Church was able to inculcate these values and loyalties without serious competition from other organizations or value systems.

The “socialization” of the second generation was particularly important in terms of leadership. A significant factor in the continuity of an organization is that its second and subsequent generations of leaders continue to share the values and norms of the founders. With all due respect to the many converts to the Church who have risen to positions of responsibility and leadership, there is a strength and a sense of continuity among those who have been raised in the Church. It was our experience in Germany, where we lived for seven years, that second generation Mormons played a disproportionately large role in church leadership, even though in many cases they were much younger than converts over whom they were called to preside.

My wife, Kay, and I analyzed the Mountain West as a leadership incubator by examining the background of all individuals called to serve in stake presidencies throughout the Church during the year 1975. (Our data was taken from weekly issues of The Church News.) We found that ninety-two per cent of all members of stake presidencies called in stakes in the Mountain West were born in the Church and ninety-five per cent of them were born in that region. The most significant data, however, is the degree to which second and sub sequent generation Mormons have provided leadership for the growth of the Church in areas outside the Mountain West. Of all those called to serve in stake presidencies in California and the Pacific Northwest, seventy per cent were born in the Mountain West. For the remainder of the United States, forty-seven per cent were from the Mountain West. Beyond the borders of the United States this does not hold true, and as a consequence the General Authorities—who are preponderantly “born in the Church” and from the Mountain West—are required to spend proportionately much more time in leadership training and instruction of non-American local church leaders.

Perhaps one of the most important consequences of the gathering of the Saints was the creation of a “socialized” second generation of members who would leave the valleys of the mountains and return to the “world” from which their pioneer forefathers fled and there provide the leadership base on which further rapid growth of the Church was made possible.

Much of what the Church is today in organizational terms is an outgrowth of the trek and the experience of the gathering. Although I have tended to look at the consequences in sociological and organizational terms, I in no way wish to underestimate the hand of the Lord in these events. Just as we are a combination of both physical body and spirit and are subject to different influences on both parts, the Church has a physical body—an organizational structure—that can be analyzed scientifically just as any other organization. At the same time, however, just as we have a spirit, so the Church is led by the spirit of revelation by men called by the Lord.

Just as the Lord uses natural laws to accomplish his purposes, the choices and decisions that were made by our inspired pioneer progenitors can be understood through both spiritual and rational means. To look at the trek and the gathering in these terms gives me greater appreciation for some commandments given in that earlier time.

As one who has no Mormon pioneer ancestors, I nonetheless claim them as a part of my heritage as a member of the Church. The law of adoption, applied to those who are not of the lineage of Joseph through Ephraim, can be applied as well to those of us who cannot claim direct descent from an ancestor who made the trek to Zion in the nineteenth century.

[1] John P. Roche, “The Founding Fathers: A Reform Caucus in Action,” in Shadow and Sub stance (New York: Macmillan, 1964), p. 92.

[2] Wallace Stegner, The Gathering of Zion: The Story of the Mormon Trail (New York: McGraw- Hill, 1964), p. 1.

[3] Ibid., p. 155.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue