Articles/Essays – Volume 10, No. 4

The Enigma of Solomon Spalding

“Every man’s life,” wrote Emerson, “is a secret known only to God.” Certainly this must be said of Solomon Spalding, much of whose story remains obsure. The events of his life suggest a pattern of disappointment, frustration and failure, as the world judges. In the inner realm of the spirit, his vivid imagination found release and solace, and brought him, in the end, some measure of that fame which eluded him in his life. Ironically, he is remembered today solely for his alleged influence on the creation of the Book of Mormon, a curious fate for one to whom revealed religion was, at best, “delusion.”[1]

Solomon Spalding was born of old New England stock at Ashford, East Ashford Society, Connecticut on February 21, 1761. As a youth he attended the academy at nearby Plainfield. In January of 1778, like others in his family, he entered the Revolutionary Army, serving in “Captain Williams’ Company,” where he is listed as “Spaulding,” though the variant “Spalding” appears most often in his later life.

On leaving the Army, he read law with Judge Zephaniah Swift of Windham. Then experiencing what one writer has called a “change of religious views,”[2] a conversion “from law to Gospel,”[3] he decided upon the ministry and, at the age of 21, entered the sophomore class at Dartmouth College. He graduated in 1785, receiving an A.M. Having “studied divinity” for a time, he became a licentiate of the Windham Congregational Association on October 9, 1787.

He entered upon his ministry on the eve of the Second Great Awakening, for whose advent the evangelical Congregationalists had prepared the way during the war time period of religious decline. According to Theodore Schroeder, Spalding was a classmate at Dartmouth of the “famous imposter and criminal,” Stephen Burroughs (1765-1840), sometime self-ordained clergy man, acknowledged counterfeiter, (ultimately) convert to the Church of Rome and a charming rogue. His Memoirs (“of the Notorious Stephen Burroughs”), published at Albany in 1811, were reprinted in 1924 with an introduction by Robert Frost. Asserting Spalding’s desire to “burlesque the Bible” and so demonstrate the “gullibility of the masses,” Schroeder, in a vigorously anti Mormon vein, goes on to suggest that Burroughs’ career of profitable fraud may have inspired Spalding—a strange idea inasmuch as Spalding’s alleged link to Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon could only be an accident of history: Spalding was dead more than a decade before the birth of the Mormon faith. Burroughs entered Dartmouth in 1781, a year before Spalding, and appears to have left under a cloud not long after. Moreover, there is no mention of Spalding in Burroughs’ Memoirs.

Ordained as an evangelist, Spalding preached for “8 or 10 years,” declining several offers of settled pastorates on the ground of poor health. His “invalidism” appears to have become a permanent condition, though alluded to vaguely. Henry Caswell, a nineteenth century professor of divinity at Kemper College, Missouri, speaks of him as deserting the pulpit “for some reason which has not transpired.”[4] More recently, George Bartholomew Arbaugh, finding a loss of faith and “uncertain morals” in Spalding’s manuscript novel, thus reads them into his life.[5] Eber D. Howe, whose Mormonism Unvailed was the first work to associate Spalding and the Book of Mormon, speaks of Spalding as “inclined to infidelity” in later life, a judgment based upon a brief statement of his (presumably later) religious views, which are not unlike those of Thomas Jefferson regarding Christian othodoxy and the Bible.

Whatever his motives, Spalding did abandon the ministry, married Matilda Sabin of Pomfret in 1795, and soon afterwards went into business with his brother, Josiah, at Cherry Valley, New York. The town was recovering from the destruction wrought by the Cherry Valley Massacre of 1788, in which many inhabitants were murdered by the Indians. Here he served also as principal of the Cherry Valley Academy (begun in 1742), the first classical school west of Albany. He also preached occasionally at the Presbyterian Meeting House in Cherry Valley: the consociated Congregationalists of Connecticut were seeking fuller rapprochement with Presbyterians elsewhere, fulfilled in the Plan of Union adopted in 1801. Several sources speak of Spalding as a “Presbyterian minister.”[6]

At least one author suggests it was while Spalding lived in Cherry Valley that he wrote his now famous romantic novel, which allegedly provided the “historical” source for the Book of Mormon. Ultimately, for reasons unknown, the trustees of the academy are said to have “called for his resignation.”[7] What is certain is that his business venture failed, and the brothers removed themselves and their store to Richfield, New York in 1799. Later they appear to have engaged in extensive land speculation in Pennsylvania and Ohio, and in 1809 Spalding moved to New Salem, Ohio (now Conneaut) to oversee his real estate deals. In New Salem he and Henry Lake opened an iron foundry as well.

The War of 1812 disrupted his business ventures and reduced him to bankruptcy and ruin. Depressed, burdened by debt and broken in health, Spalding found solace in his literary pursuits, writing a romance about the original inhabitants of America and reading portions of it aloud to entertain his friends and neighbors. It recounted the adventures of a ship’s company of Romans in the time of Constantine the Great, driven by storms to the New World and casting their lot with the Indians. It has been maintained that he shared the widespread belief in the Hebrew origins of the Indians as descendents of the Lost Tribes, a belief asserted in 1816, the year of his death, by Elias Boudinot in his Star in the West. The mounds and earthworks near New Salem had excited Spalding’s imagination regarding civilized races in America now extinct, and he was one of the first to speculate and write on the Mississippi Valley earthmounds.[8]

As a result of his difficulties in Ohio, Spalding moved his family to the Pittsburgh area in 1812. Sometime during the next two years, it is claimed, he met with a printer, the Rev. Robert Patterson, whom he hoped would publish his novel.

Apparently Spalding’s lack of money for that purpose led to Patterson’s rejection of the manuscript, and its eventual fate has become a matter of endless dispute. Was it misplaced by Patterson or simply retained for future consideration? Was it returned to Spalding and subsequently lost? Was it the manuscript discovered in Honolulu in 1884 by President Fairchild of Oberlin? Was there another novel, now lost, or was the first rewritten? Was it copied and stolen by Sidney Rigdon or an unknown stranger, as some have alleged?

Whatever the truth, Spalding moved to Amity (near Pittsburgh), where he died on October 20, 1816. Years later his home became a point of historic interest after the publication of Eber Howe’s Mormonism Unvailed in 1834 popularized Philastus Hurlbut’s allegation that Sidney Rigdon had conspired with Joseph Smith in writing the Book of Mormon, basing it upon Spalding’s “lost” manuscript romance.

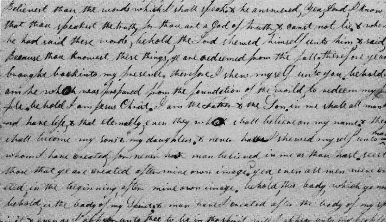

Spalding’s house was standing well into the present century. His sandstone grave marker, beset by eager souvenir hunters, had disappeared by 1899. In 1905 the town of Amity, by public subscription, raised a granite marker over Spalding’s grave in the old churchyard, and restored the text of the original inscription, which may serve as a final, if inconclusive, judgment until that Day “when the secrets of all hearts shall be disclosed.”

Kind cherubs guard his sleeping clay

Until that great decisive day,

And saints complete in glory rise

To share the triumphs of the skies.[9]

Note: All sources consulted agree that Spalding died on October 20,1816, except Edward Spalding, Spalding Memorial, who gives the date as September 10, 1816.

[1] James H. Fairchild, Manuscript of Solomon Spaulding and the Book of Mormon (Cleveland, Ohio: Western Reserve Historical Society, Tract no. JJ, March 23, 1886), 196.

[2] George T. Chapman, Sketches of the Alumni of Dartmouth College (Cambridge, Mass.: Riverside Press, 1867), 39.

[3] Samuel J. Spalding, Spalding Memorial: A Genealogical History of Edward Spalding, of Massachusetts Bay, and His Descendents (Boston: Alfred Mudge & Sons, Printers, 1872), 159.

[4] Henry Caswell, The Prophet of the Nineteenth Century (London: J. G. F. & J. Rivington, 1843), 14.

[5] George Bartholomew Arbaugh, Revelation in Mormonism: Its Character and Changing Forms (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1932), 16.

[6] Thomas Gregg, The Prophet of Palmyra (New York: John B. Alden, Publisher, 1890), 408; M. T. Lamb, The Mormons and the Bible (Philadelphia: The Griffith & Rowland Press, 1901), 33; Spalding, Spalding Memorial, 161; and History of Otsego County, New York (Philadelphia: Everts & Fariss, 1878), 127, 325.

[7] John Sawyer, History of Cherry Valley From 1740 to 1898 (Cherry Valley, N.Y: Gazette Print, 1898), 2-3, 56.

[8] Caswell, The Prophet of the Nineteenth Century 16-18; Dickinson, New Light on Mormonism, 14-15; and Pomeroy Tucker, Origin, Rise, and Progress of Mormonism (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1867), 122. Henry Steele Commager in The Empire of Reason, p. 28, notes the similar “passion for . . . exploring Indian mounds” in Ohio country by the Rev. Manasseh Cutler (1742-1823), an original organizer of the Ohio Company.

[9] Boyd Crumbrine, History of Washington County Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1882), 426; and Joseph F. McFarland, 20th Century History of Washington and Washington County Pennsylvania (Chicago: Richmond-Arnold Publishing Co., 1910), 184.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue