Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 4

The Fire of God: Thoughts on the Nature of Divine Witness

For many members of the LDS church, the word “testimony” calls up images stretched over a lifetime: fervent declarations uttered in half darkness around waning campfires, quiet successions of stories and assurances in sunwashed chapels, moments of silent illumination while poring over passages of leather-bound holy writ.

How often, though, does “gaining a testimony” become just one doctrinal topic to occupy a Sunday’s worth of priesthood or Relief Society lesson time, a matter limited to reiteration during monthly fast services? We sometimes regard the matter of testimony (even if with utmost respect) as one more gospel subject, “on the shelf” with the Atonement, the Plan of Salvation, the Law of Tithing, and so on.

We often fail to see testimony for what it is: the means for integrating all gospel truths—in fact, all truths, regardless of their source—into a unified understanding of things as they are, were, and are to come. If all gospel principles affect our salvation, the gift of divine witness is our means of truly knowing them, understanding them, and seeing them as funda mental to the life we live. The truths of the restored gospel are the path to eternal life, but, until they are real to us, they offer no more than vague comfort. Once our understanding of the doctrines of the Kingdom are fired by the witness of the Spirit, they illuminate, challenge, and guide (and sometimes drive and goad) us, the heart and core of a new and expanded reality.

Testimony—the “more sure” knowledge of God’s plan of salvation, of the restoration of his gospel, and of “the truth of all things”—un locks the essence of the Latter-day Saints’ faith. The witness of the Spirit has been held out to all men and women in our time, offering us a means of understanding all realities closed to our natural eyes. It is a new and more perfect mode of learning, not just spiritual things, but all things.

Mother of us all, O Earth, and Sun’s all-seeing eye, behold,

I pray, what I a God from Gods endure.

Behold in what foul case

I for ten thousand years

Shall struggle in my woe,

in these unseemly chains.

* * *

For I, poor I, through giving

Great gifts to mortal men, am prisoner made

In these fast fetters; yea, in fennel stalk

I snatched the hidden spring of stolen fire,

which is to men a teacher of all arts,

Their chief resource. And now this penalty

Of that offence I pay, fast riveted

In chains beneath the open firmament.

* * *

The foe of Zeus, and held

In hatred by all Gods

Who tread the courts of Zeus:

And this for my great love,

Too great, for mortal men.

—Æschylus, Prometheus Bound

One of the most powerful stories taken from Greek mythology tells of the titan Prometheus who, alone among the gods, loved mortals enough to share with them the secret miracle of fire, “th[e] choice flower … the bright glory of fire that all arts spring from,” the key to the divine vision of the gods themselves. For this blasphemy, Zeus chained Prometheus in the mountain heights of Caucasos, there to suffer for ten thousand years.

In Prometheus Bound, Æschylus retold the story in a way which has captivated Western thought for centuries, Æschylus modified and deepened the Promethean myth by casting Prometheus (whose name trans lates loosely as “forethought”) as the son of Themis, Mother Earth, and therefore blessed by birth with divine foreknowledge—the gift of prophecy. Zeus is portrayed as a young god (Prometheus’ nephew, in fact), newly exalted over the titans, devoid of foresight and driven by power and vengeance, who has determined that the human race is unworthy and must be destroyed. It is Prometheus’ foresight which instills in him enough belief in mortal man’s salvageability to prompt his theft of fire’s divine power from Olympus.[1]

Scholars have struggled for generations over the rationale behind Zeus’ unbending condemnation of Prometheus.[2] Some point out that Prometheus Bound is the first, and only surviving, of a trilogy of plays, in the last of which Zeus forgives Prometheus and is reconciled to the wisdom of his acts. Others see Zeus as nature’s god, bearing down without reason or mercy on the efforts of human deity personified by Prometheus—reason, intelligence, and enlightenment—to wrest control of the world.

Perhaps, in Zeus’ blind vengeance against Prometheus for bestowing fire on mortals, the ancient Greeks personified their own guilt, projecting onto their gods their own all-too-human ambivalence at the sharing of those divine gifts which have been so bountifully bestowed on humanity; their self-perceived inability, fear, and unworthiness (their great desires notwithstanding) to wield the Fire of God.

I

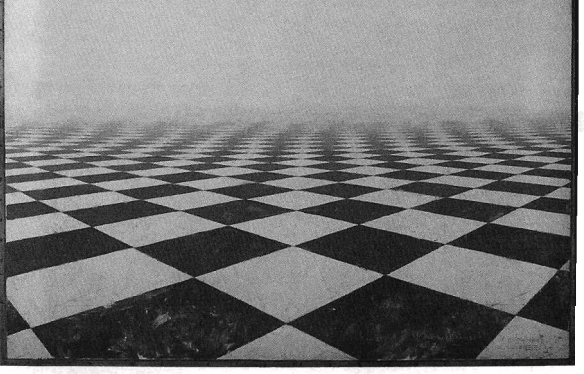

Mortality, in fact, has always imposed upon humanity just such a confounding paradox. Cut off from God by the Fall, isolated—in part, at least—in mortality (our “probationary state” [2 Ne. 2:21; Alma 12:24]), we are at once both lost to God and lost without him. In many ways we are complete beings, finding fulfillment in our lives through things we can see, touch, and experience. On a more fundamental level, though, our makeup is shot through with incompleteness—and longing. However self-contained our natural perceptions may seem, we are laden with deeper sensibilities that stretch our awareness beyond our senses. It is that part of us, for instance, which responds so profoundly, without knowing why, to unbearable beauty and soul-stirring majesty. Who has not watched a beautiful sunset, listened to the thunder of a stormy sea at midnight, gazed at the silent perfection of a mountain meadow at dawn, and not felt the presence of a perfection behind what our senses tell us? We are, at heart, a maze of thoughts and desires which fades to the edge of physical reality and aches to move beyond. All that seems perfect and wonderful in our world takes on even greater beauty when we look more closely and begin to realize that it is only the faintest echo of something more perfect and wonderful—and real; something perhaps outside our experience and full comprehension, yet central to our nature.

We are, in short, filled with whisperings of our own divine origin which, as we focus on them, fan the spark of God’s fire in each of us. C. S. Lewis’s writings speak of the “inconsolable longing” which, to him, strongly denoted the divinity of the human soul:

There have been times when I think we do not desire Heaven; but more often I find myself wondering whether, in our heart of hearts, we have ever de sired anything else….

All your life an unattainable ecstasy has hovered just beyond the grasp of your consciousness. The day is coming when you will wake to find, beyond all hope, that you have attained it, or else, that it was within your reach and you have lost it forever.[3]

For some, this divine spark fires a drive for understanding. Every answer for such individuals gives birth to a hundred questions, each leading to a wellspring of questions of its own. These are the lucky souls for whom a lifetime of learning and intellectual enrichment becomes a consuming passion. Yet, even for them, the overpowering need to understand creation as a whole leads to the outer bounds of human learning, then leaves them to gaze into an unknown which, for all our advances, is only scarcely less vast than it was for our earliest ancestors.

Others, the professed “realists,” deal with divine murmurings by hacking them off at their roots, an act of spiritual self-mutilation in which they engage as part of some misdirected passage into adulthood. At some point, they shut their hearts to the notion that the physical world is the visible aspect of something grander than they see, and conclude that what human hand can take hold of and deal with is really “all there is.” Theirs is a blindness which they view as part of “growing up.” Condemned to a self-imposed truncation of their own natures, they waver between gaiety and despair, and assume that the hope for, or belief in, anything more is childishness—not seeing that they have imprisoned themselves in perpetual spiritual adolescence.

The rest of us continue to reach for the divine in the perceivable. The entire history of human thought may be viewed, in a way, as our effort to grasp at and bind off these threads of a divine origin in the world around us. The ancients, from the beginning of history, crafted myths (some simple and straightforward, some complex and enigmatic) around the single theme of bringing the human spirit into harmony with nature and its Author. Einstein spent the final years of his life trying to knit together a coherent model of reality,[4] as did Alfred North Whitehead.[5] Some have emphasized the experiential over the theoretical, such as Thoreau, who explained his two-year hermitage on the shores of Walden Pond as a simple attempt to live the essence of life denied men in more hectic and care worn walks: “I went into the woods because I wished to live deliberately to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”[6]

But ultimately these “divine whisperings,” wonderful though they are to contemplate, give us little real illumination if taken by themselves, no matter how rearranged or reexamined. Indeed, without more, they seem almost to taunt us, hinting at a grander reality than we can grasp, offering only enough of it to engender frustration.

In fact they are far more. They are invitations.

The restoration of the gospel has brought with it a quiet, blessed response to our age-old yearning for divine contact. It explains that we were never intended to exist apart from our spiritual nature. Neither, though, were we to be left to our own devices to glean from the perceivable world around us (and our deductions therefrom) who and what we are. We are intended, “built,” to know—to know fully and directly—our transcendental nature as offspring of God. Until we do, what else we know is rough and unfinished, like Prometheus’ view of men without the fire of Olympus: “Like the shapes of dreams they dragged through their long lives and handled all things in bewilderment and confusion …” We are complete, we can function properly and fully, only when illuminated by the direct witness of the Holy Spirit. Through its teachings and testimony, we come to know ourselves fully, to understand the world in which we find ourselves, and find both strength and wisdom to deal with the life we are given to lead. And unlike Prometheus, whose act of sharing the divine fire was heresy in the eyes of the gods, the Holy Ghost shoulders a divine, eternal commission to bear witness to every soul of the Fire of God that burns within them.

II

From the beginning, the prophets’ teachings have revolved around the individual quest to cultivate the witness of the Spirit. King Benjamin spoke to the Nephites of those impulses in the human soul—”enticings of the Holy Spirit” (Mosiah 3:19)—which prompt us to reach for God. Only by yielding to these enticings, he assured them, could one “put off the natural man” (ibid.)—that is, the incomplete being each of us is when trying to live cut off from our heavenly parents.

During his earthly ministry, the Savior labored to bring his apostles to an understanding of the Spirit as the only sure means of insight into spiritual things. In the parable of Lazarus and the rich man, Christ drove home the fact that, absent faith in the words of the prophets, no miracle— even one rising from the dead—would make a believer of an unbeliever (Luke 16:20-31). Yet when Simon Peter, trusting in the Spirit’s voice, declared Jesus the Son of the Living God, Christ rejoiced and proclaimed that Peter had been visited with divine knowledge: “Blessed art thou, Simon Bar-Jona: for flesh and blood hath not revealed it unto thee, but my Father who is in Heaven” (Matt. 16:17).

Paul likewise assured the saints at Rome and Corinth of the reality of the Spirit’s witness:

The Spirit itself beareth witness with our spirit, that we are the children of God (Rom. 8:16).

But God hath revealed [them] unto us by his Spirit: for the Spirit sear cheth all things, yea, the deep things of God.

For what man knoweth the things of a man, save the spirit of man which is in him? even so the things of God knoweth no man, but the Spirit of God.

Now we have received, not the spirit of the world, but the spirit which is of God; that we might know the things that are freely given to us of God.

Which things also we speak, not in the words which man’s wisdom teacheth, but which the Holy Ghost teacheth; comparing spiritual things with spiritual.

But the natural man receiveth not the things of the Spirit of God: for they are foolishness unto him: neither can he know [them], because they are spiri tually discerned.

But he that is spiritual judgeth all things, yet he himself is judged of no man.

For who hath known the mind of the Lord, that he may instruct him? But we have the mind of Christ (1 Cor. 2:10-16; emphasis added).

The prophets of the Book of Mormon likewise turned the minds of their listeners to the Spirit’s voice. In bearing testimony to the people of his land, Alma assured them of the divine source of his wisdom:

And this is not all. Do ye not suppose that I know of these things myself?

Behold, I testify unto you that I do know that these things whereof I have spoken are true. And how do ye suppose that I know of their surety?

Behold, I say unto you they are made known unto me by the Holy Spirit of God. Behold, I have fasted and prayed many days that I might know these things of myself. And now I do know of myself that they are true; for the Lord God hath made them manifest unto me by his Holy Spirit; and this is the spirit of revelation which is in me (Alma 5:45-46).

In our own dispensation, the Lord spoke through his prophet to re veal, in personal detail, the nature and process of spiritual illumination:

Oliver Cowdery, verily, verily, I say unto you, that assuredly as the Lord liveth, who is your God and your Redeemer, even so surely shall you receive a knowledge of whatsoever things you shall ask in faith, with an honest heart, believing that you shall receive a knowledge concerning the engravings of old records, which are ancient, which contain those parts of my scripture of which has been spoken by the manifestation of my Spirit.

Yea, behold, I will tell you in your mind and in your heart, by the Holy Ghost, which shall come upon you and which shall dwell in your heart.

Now, behold, this is the spirit of revelation; behold, this is the spirit by which Moses brought the children of Israel through the Red Sea on dry ground….

And, therefore, whatsoever you shall ask me to tell you by that means, that will I grant unto you, and you shall have knowledge concerning it.

Remember that without faith you can do nothing; therefore ask in faith (D&C 8:1-3,9-10).

To twelve elders assembled at Kirtland, Ohio, in February 1831, the Lord gave assurance of their right to personal revelation, again offering an intriguing characterization of spiritual insight: “If thou shalt ask, thou shalt receive revelation upon revelation, knowledge upon knowledge, that thou mayest know the mysteries and peaceable things—that which bringeth joy, that which bringeth life eternal” (D&C 42:61).

This, then, is the ultimate promise of testimony, of divine witness. If we ask, if we knock, if we disenchant ourselves for a moment from our own cleverness and insights and embrace the possibility of a reality be yond our natural eyes, there awaits each of us a revelation of the mysteries of heaven—”the peaceable things”—which is nothing less than the eyes and mind of God himself.

III

All this brings us back to the dilemma framed in the Promethean myth. Why is it so hard for many of us, both inside the church and out, to accept the proffered gift of divine witness? Among Mormons and gen tiles alike (albeit for different reasons), there is a common tendency to confine, to trivialize, the nature and scope of divine witness, either to discredit those who espouse it or to simplify and render it more comprehensible.

Critics of gospel doctrines often dismiss the holding of testimony as simply one more variation on religious conviction. They characterize the witness of the Spirit as the internal reinforcement of our credo, a self-induced reaffirmation of teachings and traditions given by our forebears. Our beliefs feel good to us, they explain, because they are an extension of ourselves, our heritage, our upbringing, our values. We simply extend the familiar into the realm of the cosmic, so the argument goes, in order to make the cosmos more comfortable.

Now there is surely a degree of reaffirmation of belief and tradition inherent in spiritual witness. It is the calling of the Holy Spirit, first and foremost, to bear record of the Father and the Son.[7] But the vista seen through the eyes of the Spirit need not, and must not, end there. Spiritual witness, even in its first faint whisperings to an untried and uncertain believer, is far wider and deeper than the unbeliever imagines. It is not limited to promptings that we believe in virtuous or “right” things, nor a reaffirmation of Christ’s divinity and the gospel’s truth. Often it visits us with insights into the inner workings of our world, showing us clearly all-embracing truths never suspected by those confined to empirical reality, for whom such things are “foolishness . . . because they are spiritually discerned” (1 Cor. 2:14). At other times the witness offers us glimpses into the intimate parts of our own makeup as God’s offspring, bringing us into closer harmony with our true nature and with nature as a whole.

But it is always too unexpected, too “outside” of ourselves, to explain away as a mere extension of our own wishes. Indeed, a defining characteristic of divine witness is the keen, sharp awareness that we are receiving something from outside ourselves, from somewhere—and someone—else. If divine witness were only an extension of ourselves, no more than a projection of our own ideas and preconceptions, its manifestations and promptings would undoubtedly appear more familiar, more in harmony with our natural side. Why, when it comes, is it often jarring, demanding that we be something more than we are? It is precisely when the promptings of the Holy Ghost propel us in an unexpected, counterintuitive direction that we most sense its “otherness,” its otherworldly and divine impact on our worldly doings.

It may, in fact, be this very uncertainty that often creates a stumbling block to well-meaning souls in Christ’s church. For many, such startling intrusions are the last thing they want from their faith. These are the Saints who hope to shelter behind the gospel to avoid growth or change. They seek not spiritual enlightenment but doctrinal blinders; not illumination but rigid constancy to spare them the discomfort of change or growth. Both the stretch entailed in attaining spiritual insight to begin with, and the uncertainties once it has been given, are unwelcome disturbances from what they view as the rightful source of calm, peace, and constancy in life.

It may seem harsh to dismiss such longings as wishful thinking, but that is ultimately what they are. It is natural enough for us to seek the comfort and predictability of a set of fixed (and hence controllable) rules defining spiritual reality—after all, we take comfort in our ability, as rational beings, to predict and manipulate the laws of nature for our bene fit, and part of us would have the same qualities in our God. But spiritual truths refuse to behave that way. Quoting again from C. S. Lewis: “If you look for truth, you may find comfort in the end: If you look for comfort you will not get either comfort or truth—only soft soap and wishful thinking to begin with, and, in the end, despair.”[8]

Those willing to listen to and learn from the witness of the Spirit, finally, must leave behind notions of comfort and predictability. That is the last thing a discoverer should expect. Spiritual truth is like any other: stubborn, multi-dimensional, unexpected, uncooperative, unwilling to mold itself around our preconceptions. Truth, all truth, is “knowledge of things as they are, as they were, and as they are to come” (D&C 93:24), in all their obstreperous and independent wonder. Voyagers into the realms of spiritual knowledge must brace for unexpected jolts—some joyous, others less so—before journey’s end. Spiritual eyes, no less than worldly eyes, must be willing to shed illusions in order to see clearly.

IV

Where, then, does one start in kindling divine fire? We have been blessed, in our day, with the word of God. The Restoration has placed at our fingertips scripture from both the Old and New worlds; modern rev elation through early latter-day prophets has augmented the body of ancient scripture with words intended specifically for our day; living prophets and apostles speak directly and plainly to the challenges and questions of the present-day world. Ironically, we find ourselves, in this secular age where so many doubt the divinity of any writ or message, beneficiaries of an unprecedented outpouring of God’s word, his “blue print” for spiritual understanding. Those willing to make the trial need never lack for raw materials.

But raw materials are really what such matters are. Scriptures, conference addresses, sound though their counsel may be, useful as their guidance clearly is to living a good life, are given for guidance and impetus, not witness. It has been said that the whole purpose of the gospel’s teachings is, first and foremost, to get us on our knees before our Maker. The Savior condemned the Pharisees for the slavish devotion to holy writ which blinded them to the identity of its Author and Finisher: “Search the scriptures; for in them ye think ye have eternal life: and they are they which testify of me” (John 5:39). Paul labored to shift the attention of the early saints away from the letter of the law to its spirit: “Wherefore the law was our schoolmaster to bring us unto Christ, that we might be justified by faith” (Gal. 3:24).

The principles and teachings of the gospel furnish the fodder for the divine fire of spiritual awakening; it is our willingness to petition in prayer for a personal witness that sets the spark. Alma knew well what was at work in the hearts of the Zoramites when, having planted the seed of gospel truth in his listeners, he implored them, “If ye can no more than desire to believe, let that desire work in you” (Alma 32:27).

Now, we will compare the word unto a seed. Now, if ye give place, that a seed may be planted in your heart, behold, if it be a true seed, or a good seed, if ye do not cast it out by your unbelief, that ye will resist the Spirit of the Lord, behold, it will begin to swell within your breasts; and when you feel these swelling motions, ye will begin to say within yourselves—It must needs be that this is a good seed, or that the word is good, for it beginneth to enlarge my soul; yea, it beginneth to enlighten my understanding, yea, it beginneth to be delicious to me (v. 28).

What Alma was urging is a willingness to step back from the reality against which we are commonly pressed flush and peer around its edges. Until we are willing to listen to our more fundamental selves, and to believe, or even just to hope, that there is more to our world than what meets the eye, we will be slaves to the empirical, and no larger spiritual reality will have place in our perceptions. Only when we accept that there is another way to view things, another vantage point from which we may take on a different countenance, can the voice of the Spirit whisper confirmation and open the panorama to our gaze.

If we have thus prepared the ground properly, the witness of the Spirit, the fire of God, breathes life into the doctrines of salvation and drives home the reality of the restored gospel. With its coming, in what for some is a sudden rush of pure illumination from beyond ourselves, and for others an imperceptibly slow-growing realization, we understand: the teachings of the gospel, the comforting assurances of God’s love and concern and of life everlasting, are not mere security blankets offering shelter from a cold world. They are glimpses of a reality beyond our natural field of vision. It is all really out there.

And it is breathtaking. With time, the presence and input of the Spirit’s voice can, and should, become a central facet of existence. Every marvel in creation takes on new significance, new depth, as a confirmation of what he has spoken to us.[9]

V

Where to from there? Once the Spirit’s prompting has become our tutor, our own limitations mark its only confines. It has already been mentioned that the scope of spiritual vision sweeps wide, instructing us in far more than God’s reality alone. But how wide? What limits are there to the things we can know through the Holy Ghost?

According to the prophets, there are none. During mortality the Savior gave assurance without qualification: “Ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you: For every one that asketh receiveth; and he that seeketh findeth; and to him that knocketh it shall be opened” (Matt. 7:7-8). Nephi assured diligent seekers to find “the mysteries of God. . . . unfolded unto them, by the power of the Holy Ghost” (1 Ne. 10:19). The Lord, speaking through Joseph Smith, gave similar assurances to those who fear, love, and follow him:

And to them will I reveal all mysteries, yea, all the hidden mysteries of my kingdom from days of old, and for ages to come, will I make known unto them the good pleasure of my will concerning all things pertaining to my kingdom. Yea, even the wonders of eternity shall they know, and things to come will I show them (D&C 76:7-8).

Moroni, even in the wake of utter destruction of his people, offered assurance to generations to come: “And whosoever shall believe in my name, doubting nothing, unto him will I confirm all my words, even unto the ends of the earth” (Mormon 9:25). In the final words of his lonely record, Moroni, typically straightforward, summed up the scope of divine knowledge: “By the power of the Holy Ghost,” he stated simply, “ye may know the truth of all things” (Moro. 10:5).

The truth of all things. If we ask in faith, believing that we shall receive, each of us has the promise that there is—ultimately—no wisdom that will be denied us. Far from buttressing a narrow range of preconceptions and confining us to rote revisitation of a handful of aphorisms, real spiritual insight explodes our horizons, letting us glimpse the entire firmament of revealed truth in seamless completeness.

Now there will no doubt be those for whom these sweeping assurances, however faith-promoting and grand they sound, ring hollow in actual experience. Perfect knowledge is hardly the norm among the Saints, after all. Even the best mortals see only so far. Local and general authorities regularly chafe under the foibles and limitations common to all hu mankind. Even when the righteous seek divine guidance in certain particulars, it is not always forthcoming. Who among the faithful has not sought wisdom in prayer, yet turned away bewildered?

The entire vision of eternity is not instantly ours (see, e.g., D&C 9:7). The scope of our spiritual sight is always subject to our own limitations. No degree of faith is going to open our eyes to mysteries and marvels be yond our comprehension. If the time is not yet, the comprehension too tenuous or the pain too deep, for the truth, knowledge will be lovingly withheld until it can truly illuminate without overwhelming. “The truth of all things” is our legacy, but it must to a degree come in the Lord’s time, as his children are ready to receive. Growth in wisdom, experience, and ability to reflect God’s plan in our actions brings increased vision until, in the end, knowledge cannot be withheld from us—like the brother of Jared, we will see all because nothing can keep us out (Ether 3:20). “[H]e that receiveth light, and continueth in God, receiveth more light; and that light groweth brighter and brighter until the perfect day” (D&C 50:24).

VI

“Whole sight,” wrote John Fowles in the voice of his fictional alter ego, Daniel Martin, “or all else is desolation.”[10] The ultimate weakness of the human condition is our inability to experience reality in context, to “see nature whole.”[11] Perceived reality is disjointed, often oppressive, in explicably harsh, conducive to depressives and cynics, but very hard on all but the most irrepressible idealists.

It is the vision of the Spirit which offers mortals whole sight. Even if, at the outset, we are not given a full understanding of every facet of that reality, yet what we do see is bathed in pristine illumination. And that, perhaps, is the ultimate gift of the Spirit: a view of our world in the light of God, bright beyond any despair or cynicism, whole and complete past all efforts at analysis and dissection. If every question does not have an immediate answer, the unspeakable assurance that we have someone to put the questions to and that, in time, we will understand “the truth of all things” carries us past doubting and fearing and sets us, hesitant and halting, on the path of learning. For the Fire of God brings not blindness, but sight, knowledge, and wisdom at our most profound level.

Contrast the curse of the Greek gods upon Prometheus with the Father’s efforts to pour the light of the Spirit onto the heads of his children. “God is giving away the truths of the universe,” said Elder Neal A. Max well, “if only we will not be offended by his generosity.”[12] The gospel is the truth; the Spirit will let us see it and, through it, everything else. It is real, all of it. It is there for us if we will seize it, drink it in, let it transform us, and find the courage to live in and through its illumination.

[1] See Warren D. Anderson, trans., Prometheus Bound (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Educational Publishing, 1963), xv-xxii; C. John Herington, trans., Prometheus Bound (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975), 6-18; D. J. Conacher, Æschylus’ Prometheus Bound: A Literary Commentary (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1980).

[2] See summary in Conacher, 120-37.

[3] C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain (London: MacMillan Publishing Co., 1943), 148.

[4] See, for example, Albert Einstein and Leopold Infeld, The Evolution of Physics (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1938).

[5] See, for example, Alfred North Whitehead, Essays in Science and Philosophy (New York: Philosophical Library, Inc., 1948).

[6] Henry David Thoreau, Walden, or Life in the Woods (New York: George Macy Companies, Inc. 1939), 97.

[7] Joseph Fielding Smith, Doctrines of Salvation, 3 vols. (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1954), 1:38.

[8] C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1943), 39.

[9] See Francis M. Gibbons, David O. McKay (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co. 1986), 50.

[10] John Fowles, Daniel Martin (New York: Doubleday & Co. 1977), 1.

[11] John Fowles, “Seeing Nature Whole,” Harpers 259 (Nov. 1979): 45-59.

[12] Neal A. Maxwell, comments at the dedication of the Bountiful temple, 8 Jan. 1995, notes in my possession.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue