Articles/Essays – Volume 04, No. 1

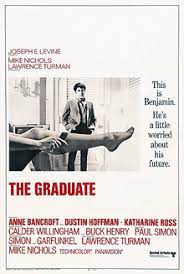

The Graduate | Mike Nichols, dir., The Graduate

This is a very disturbing film. Members of the Church ought to be warned to avoid it and to keep their children away from it. Its philosophy is “loaded”! It assumes that the immoral is acceptable and that proven American values are not worth observing. I cannot help but wonder what our Father in Heaven must think of the people who produced this film, let alone the curious L.D.S. people who flock to see it.

The film is about what appears to be a Jewish family in Los Angeles whose son has just returned from four years of college. The son looks Jewish, anyway. No mention is made as to whether or not the family is orthodox in their Jewish faith. I consider this to be one of the major flaws of the film. Another incomprehensible thing to me is that singers Simon and Garfunkel (also Jewish) expanded their “Mrs. Robinson” song to include lines about Jesus, in whom Jewish people do not even believe. They have the gall to sing “Jesus loves you more than you will know. .. .”

Anyway, the story opens with a homecoming party for Benjamin, the “hero” of the film. Everyone there is perfectly nice to him, but he stalks off to his room and sulks. Nobody can figure out why, including the audience. I talked to at least fifty people in Rexburg who saw the film the same night I did, and none of us knows why he stalked off to his room.

While he’s in his room, a woman old enough to be his mother-in-law lures him out into her car, over to her house, and up to her room where she disrobes and stands naked before him. “Jesus Christ!” he shouts, as though he believes in Jesus. The lady’s husband comes home and the boy runs down stairs to the bar. Supposedly the husband doesn’t know what’s been going on, but I think he did know because when the boy asks for bourbon, the husband pours him scotch. The husband is no dummy: he is a successful lawyer.

Then follows what is perhaps the most disgusting part of the film: The boy phones up the older woman and invites her over to a hotel room (because he is “bored,” he explains later). The moviemakers actually show them in bed together! To try to make the scene palatable to the audience, the writers try to show that Benjamin is a respectful boy by having him call the older woman “Mrs. Robinson” even in the midst of their most intimate moments. But the writers could not pull it off, for the audience suspects that when Benjamin calls her “Mrs. Robinson,” he is cynical about it, and therefore is not genuinely sincere about being respectful.

The boy’s father and mother try to get him to take out Mrs. Robinson’s daughter Elaine, but Mrs. Robinson is against it. However, he does take her out anyway, because his parents insist. Cruelly, Benjamin makes Elaine cry by challenging her to try to duplicate the act of a bump and grind dancer who can twirl propellers positioned in vulgar places. Anyway, Benjamin kisses Elaine and they begin to fall in love.

Elaine finds out that Benjamin has been having an affair with somebody. But she doesn’t seem very concerned about it (probably because she has been going to school at the University of California at Berkeley). In other words, the message that comes across to the young people watching the film is that it is acceptable for young men to have affairs.

Of course when Elaine finds out that the object of Benjamin’s attentions has been her own mother, this turns out to be too much even for a Berkeley student. She returns to school, and Benjamin follows her north. He finds himself competing for her affection with a nice-looking, neat, blond-haired, blue-eyed medical student. By contrast, Benjamin is slovenly, footloose, and a college dropout. What she sees in Benjamin is almost beyond the comprehension of the audience. Perhaps the real secret is that Benjamin looks Jewish and the medical student looks Nordic, and the Hollywood producers (many of whom are also Jewish) want to show that a Jewish hippie is more attractive than the finest example of traditional American young manhood. Maybe this goes over big in New York City, but not in Zion where most people are of Ephraim and not of Judah.

With all the cunning of the Adversary, Benjamin woos Elaine and nearly persuades her to marry him, when suddenly her father arrives to talk some sense into her head. Elaine leaves Benjamin a note of regret, and her parents arrange a secret wedding for their daughter and the medical student in Santa Barbara. But by stealth and cunning, Benjamin discovers the location of the wedding by misrepresenting himself to the fraternity brothers of the medical student. Benjamin rushes down the coast in his sports car.

Now follows the most blasphemous part of the film. When Benjamin arrives, the essentials of the wedding ceremony are already completed. Elaine is legally married to the medical student. Finding himself up above and to the rear, in a glassed-in balcony, Benjamin commences to bang on the window, his arms extended outward, shouting, “Elaine! Elaine! Elaine!” almost as though he were Jesus crying “Eli, Eli, lama sabach-thani?” Rather than raising a sponge filled with vinegar to his lips, the wedding party lifts its curses to Benjamin. Yet Elaine calls out for him. This sets in motion the rescue tumult that rocks the church, as though “the veil of the temple was rent in twain from the top to the bottom; and the earth did quake, and the rocks rent.” Somehow Benjamin manages to find Elaine’s hand, and pulls her out the front doors, jamming them with a large cross which he has been swinging to ward off attackers. In other words, the cross of Jesus is used to prevent the decent and civilized and law-abiding wedding attenders from stopping the anarchistic Benjamin from running off with another man’s wife.

Benjamin and Elaine board a bus and ride away. He has triumphed. There he sits with his dazed catch, lovely in her wedding dress. Benjamin, smiling and reminiscing, looks like a hippie. If the play were Faust rather than The Graduate, we would be at the point where Mephistopheles is belly laughing at seeing Marguerite surrender to the devilish wiles of Faust. In Faust, Marguerite leaves the “hero” and repents and is saved. No such hope is offered for the heroine in The Graduate.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue