Articles/Essays – Volume 32, No. 1

The Last Code Talker

DZEH-NESH-CHEE-AH-NAH-TSIN-TLITI-TSAH-AS-ZIH. Elk-Nut-Eye-Match-Yucca.

His grandfather used to say the bilagaanas always come in twos.

The first time he was barely five years old, playing on a sand dune near their hogan west of Valley Store.

He was the first to see it: a black speck crawling like a giant beetle across the empty valley. He called to his grandfather, who was mending a bridle in the shadehouse: “Shicheii!”

The old man hobbled out into the summer glare, visoring his eyes with a gnarled hand. He watched the speck grow bigger and bigger until he knew that it wasn’t a horse or a wagon but something altogether different.

“Chidi,” he said, because the word echoed the sound of the machine: chid chid chid chid. The cloth band circling his head was as blue as the desert sky. His silver-streaked hair was bound with white yarn in a tight little bun just above the nape of his neck. Black and shiny as a crow’s wing, the boy’s hair was long like his grandfather’s, and he wore it in the same manner, with pride.

The boy’s mother rose slowly from her loom. A few feet away, his baby brother was strapped snugly in a cradleboard, quietly observing the activities of day’s end.

The chidi stopped, and two bilagaana men climbed out. Both wore black cowboy hats and droopy mustaches, and both carried long-guns with grace and ease, as if they were natural extensions of their bodies. They offered no greeting, no token ya’at’eeh. They marched towards the sheep corral silently, side by side, like shadows of each other, like snake eyed gunslingers in a TV western. The taller man loosened a wire loop and pulled back the gate. The shorter man slipped inside, braced the butt of the long-gun against his shoulder, and fired.

A scarlet dot appeared on the white flank of the boy’s favorite ewe. Within seconds it blossomed into a big red sun.

The rest was a blur, or a bad dream: more gunshots, more red suns. The sheep crowded desperately into the far corner of the corral, crying out like children being punished for something they hadn’t done.

His grandfather staggered forward, flailing his skinny arms like a scarecrow come to life, pleading in a language the bilagaanas would never understand: Why are you doing this evil thing? Why are you killing my children?

The taller man shoved the barrel of his long-gun into the old man’s belly and snarled at him in the dog-bark tongue of the bilagaana: “Step aside! Unless you wanna join the animals!”

The boy’s mother was screaming, and his grandmother too, charging out of the hogan, waving her arms like sticks: “Doo-da! Doo-da!”

The short man kept firing while the tall man blocked the gate.

And then it was over. Blood was splattered everywhere, like a rainstorm in red. The boy’s grandfather cradled the head of a fallen sheep, groaning: Why are you doing this evil thing? Why are you doing this to my family?

The shorter man sidled out of the corral, while the taller one secured the gate. They marched back to their machine in silence, their long-guns angled earthward, their boots gouging the red sand.

The bilagaanas called it Livestock Reduction, and they did it to save the Indians.

***

“I do not understand this thing that you call sin.”

“It is when you do something bad. Like lying or cheating or stealing.”

“What happens if you make a sin?”

“You will be punished. God will punish you.”

“I am confused. You say God loves us. Then why would He want to punish us?”

“He punishes us because He loves us. Like a father who punishes his children.”

“I never punished my children. Not like your God punishes His children.”

“You never—”

“No. If my children did something wrong, I would just put my arm around them and talk to them. I would tell them a story. I would say, ‘Look at this thing that you did. This is what has happened because of the thing that you did. Why did you do this thing? You have embarrassed yourself and your family.’ Why can’t your God talk to his children this way, instead of punishing them all the time? Instead of getting mad and burying everybody under water? Why can’t your God control his temper?”

***

Dzeh-A-chin-Dibeh-yazzie-Tkin-Klesh-A-woh-Ah-nah-Lha-cha-eh. Elk-Nose Lamb-Ice-Snake-Tooth-Eye-Dog.

One thought went through Elder Dawson’s mind as the Chevy LUV pick-up banged its way towards the sunburned mesa: it’s a long way from the beaches and shopping malls of southern California.

And that distance seemed to double by the minute. Since exiting the main highway over two hours ago, Elder Buck had followed one dirt artery into another until they seemed hopelessly lost in a maze of unmarked crossroads. At every fork, Dawson recalled with irony the Robert Frost poem he’d memorized in freshman English: “Two roads diverged in a narrow wood, and being one traveler long I stood … “

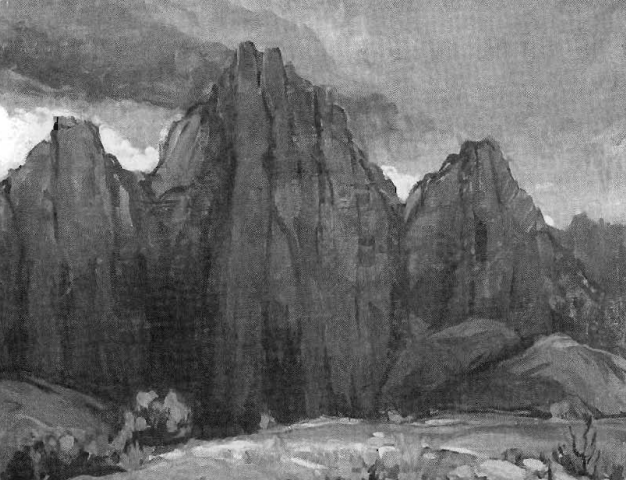

Except there were no woods here. Sagebrush, plenty. And tumbleweed, lizards, gramma grass, Pennzoil cans (“Navajo sunflowers,” Elder Buck quipped) scattered across an eternity of desert.

His Grandpa Charles had spoken nostaglically of the good old days when whole families had traveled by horse-drawn wagons to the trading post. Adorned like postcard portraits, mother and grandmother would exchange their hand-woven rugs for flour, sugar, coffee, salt, lard. Candy, too, from a glass jar on the counter. Closing his wattled eyes, drifting back, Grandpa Charles had described the seasonal fairs and rodeos, the yeibicheii dances, the Old People telling winter stories late into the night. He had extolled their wit, their sense of humor: “Dirt poor in the things of the world, but wonderful people! Humble! Spiritual! God’s children all!”

“An inspired call!” he had declared, re-reading the crisp stationery signed by the First Presidency.

Carl Dawson had countered softly, “Aren’t all mission calls inspired?”

Sensing a kindred spirit (for he too had marched to the beat of a wayward drummer in his youth), the old man had smiled. “Yes, but this one was double-inspired!”

He had reminded his grandson that he had served an early mission on the rez and that his Great-Uncle Leland had labored among the Lamanites with Jacob Hamblin. “It’s in the blood!” he had beamed.

Grandpa Charles had not told him about the aloofness of the people, frozen frowns on sandstone faces. He had not forewarned him about the adlaanis begging for “a couple dollars” to buy bread or gas or Pampers, an offering that translated into a trip to Billy the Bootlegger. He hadn’t spoken about the six-inch cockroaches that God had endowed with eternal life, no matter how many times you smashed them with your shoe, or the mud up to your knees every time it rained, or the end-of-the world loneliness of staring into a sandstorm so thick you couldn’t see your hand in front of your face.

And he hadn’t mentioned self-righteous, know-it-all senior companions, who subjected you to their personal grail of accumulating numbers.

Two years, Dawson brooded. The world will pass me by.

His horsey teeth clenched with resolve, Buck downshifted into second as the Chevy dipped into another arroyo, the rear bumper scraping against a half-buried boulder. When the road split again, he shamelessly spun the wheel to the left, sending them (once again) back from where they had just come. Dawson lost it: “Hey, is this eeny-meeny-miney-moe or what?”

Buck’s blue eyes remained on the road, as if he were double-sighting down the barrel of a rifle. “Just following the Spirit,” he said. Adding a laugh. “Trying to anyway.”

“Right,” Dawson grumbled. “Straight to Zanzibar.”

But within five minutes, something happened that would forever grant Elder Leon Buck at least partial redemption in Dawson’s eyes and give credence to the rumor that his senior companion had been born with the Liahona stuck between his ears.

***

Tsa-e-donin-ee-Wol-la-chee-Tkin-Gah-Than-zie-Dah-nes-tsa-Be-la-sana-Be Dzeh. Fly-Ant-Ice-Rabbit-Turkey-Ram-Apple-Deer-Elk.

After that, whenever the boy saw a chidi approaching, he would scamper behind the sand dune or the outhouse and wait until the bila gaanas gave up and drove away. When they asked, his mother shrugged: I don’t know! I don’t know! This worked for almost two years.

She wanted to keep him at home as long as possible because he was her firstborn. His grandfather wanted to keep him because he was differ ent. His upper lip was twisted and he ate with his left hand. The grandmother said it was because her daughter had accidentally looked at the full moon when the boy was still growing inside her. There was nothing they could do about his lip, but they tied his left hand behind his back, forcing him to use his right. Instead of curing him, it made him ambidextrous, which would prove a blessing on the basketball court. In time he would mature into the best point guard in the history of Talking Rock Boarding School.

There was something else, though. He had magic ears. Anything he heard he remembered. One day while he was singing by the sheep corral, his grandfather asked, with more astonishment than curiosity, “Where did you learn that song, my grandson?”

The boy confessed: “I heard you singing in the hogan during the Blessing way.”

After that, any time his grandfather performed a ceremony, he told the boy to sit by the hogan. He couldn’t see inside because of the blanket hanging in the doorway, but he could hear everything. Whenever they slid an empty pot outside, he would run and fill it. Everyone thought: That’s why he’s there, to fetch water. But the real reason was for him to learn the sacred songs.

When he was seven, the bilagaanas came again. This time it was Mr. Forrester, the trader and a government man. Mr. Forrester wore a brown hat and limped like a tired old horse. He was carrying a new pair of shoes, shiny black ones like the bilagaana women wore to church.

Grandfather watched quietly from the shade house while the mother stepped forward to meet the two men. She was wearing a pleated skirt and a velveteen blouse the color of late autumn. She called to the boy, who was hiding behind the sheep corral. When he didn’t come, she called again, roughly: Hago! She called a third time, and the fourth time he had to oblige.

The trader said something in Navajo. The government man opened a small metal box with a black pad inside. The mother pressed her thumb on the black pad and then on the sheet of paper the government man held out to her. The trader nodded and handed her the shoes. She leaned down and whispered to the boy: “You have to go with these two men now. If you don’t, they’re going to put me in jail.” She had been in the shadehouse making fry bread over a campfire, and her hands were coated with flour. When the trader shook her hand, the boy could hardly tell hers from his—it looked so white.

The government man smiled, his mouth sparkling gold and silver.

***

A-kha-Na-as-tso-si-Ah-nah-A-chin-Klesh. Oil-Mouse-Eye-Nose-Snake.

Almost five summers had passed since the fog in his eyes became permanent, and he could no longer read symbols in the sky. On a good day, though, he could still discern one blur from another, especially one in motion. That afternoon, as he whooshed his sheep back into the corral, he noticed a peculiar red speck circulating around the valley. For an hour he watched as it crossed and re-crossed its path in redundantly intersecting circles. Then, suddenly, like a horse that senses the corral on its homeward journey, it began barrelling across sagebrush and sandstone towards his plywood home. Thomas shook his head, muttering to himself. “Bilagaana doo yaa shoon da!” Crazy whiteman!

***

Dibeh-Shi-da-Bi-so-dih-Dzeh-Gah-Cha-Ah-jah-Dah-nes-tes-A-kha. Sheep-Un cle-Pig-Elk-Rabbit-Hat-Ear-Ram-Oil.

He’d been young and stupid and thought he was invincible. Thought if he got in a head-on doing a hundred and twenty, at worst he’d be in a coma for a week maybe. Then he’d snap out of it, good as new. He was going to be a hero. He’d show those Gooks which end was up. He was going to come home covered with medals. Strut in front of every girl that ever shafted him in high school. They’d see.

His first month out he was too scared to take his boots off. He wanted to be ready to run just in case. On day thirty-one he finally peeled off his socks. He found three layers of skin inside and a stench like rotten bananas. That scared him more than the machine guns. And the damn monsoons. He was always wet, drenched to the skin—marching, sleeping, eating. The rain was worse than bullets falling from the sky.

***

Ah-nah-Be-No-da-ih-Moasi-Wola-la-chee-A-woh-Yeh-hes-Tlo-chin-Tsah. Eye Deer-Ute-Cat-Ant-Tooth-Itch-Onion-Needle.

It was August, always August, and the heat and sweat and sockless feet of the fifty other boys and girls filled the bus with an over-ripe smell that would always remind him of late summer. Through the fog-dust he watched in awe as buttes and mesas raced by. The red rock cliffs became Monster Slayer, Child Born of Water, Changing Woman. He wondered how they could move so quickly without legs, like a fast horse. Like a human.

At first he was too full of curiosity to be scared. He pressed his hand against the glass, the metal paneling, the cracked vinyl seat. He glanced at the boy sitting next to him, touched the hot chrome frame. “Sido,” he said. Hot. The other boy nodded. “Aoo,” he replied. “Sido.” He pinched the little red thread on the box of Crackerjacks he’d been hiding under his shirt, pulled back the top, and filled the boy’s cupped hand with carmel coated peanuts and popcorn.

They arrived after dark. There were four long, flat buildings, big boxes with rows and rows of yellow eyes. A fat bilagaana met them as they got off the bus. His head looked like a melon, and he spoke as if his mouth were asleep, trying to wake up, so they called him Atsi’ Ta’neesk’ani ligaii, Melon-Head. He couldn’t understand what Melon Head was saying the first time, but that was okay because he said the same thing every year. After the third time, he knew his routine by heart:

“Ya-ta-hey! Ya-ta-hey! Welcome to Talking Rock Boarding School! There’s lots of things you need to learn, lots of things that aren’t your way. But that’s why you’re here, to learn the right way and forget the old way. That’s why we don’t talk Navajo here. Do you understand? We don’t talk Navajo at school.”

Mr. Chee wore a silver belt buckle that was half-hidden by his belly. He told them everything in Navajo. His translation wasn’t word for word, but it was much more accurate: “Look at White Eyes when he’s talking to you. If you don’t, he’s going to get mad and beat you. Do you want him to beat you? Then you’d better look him in the eyes. He’s a mean old man and he’ll do mean things to you if you don’t do everything he says. . .”.

That night the conditioning began. The girls went one way, the boys the other. They were herded like sheep into a room with a wall like frozen water: when you looked at it, you saw yourself looking back. A bilagaana as big and hairy as a bear pointed to a wooden folding chair, and a Navajo man told the boy to sit down. The boy heard a loud buzzing sound, like a hive of angry bees, and a hot iron branded the back of his head. He tried to run, but the bear grabbed his neck and slammed him back into the chair: “Got a wriggler here, Jimmy!”

The boy lowered his eyes and watched as his black hair rained onto the floor. When the buzzing stopped, he looked at the wall of frozen water and felt sick: his head was naked, naked and ugly like Mr. Melon Head’s. He tried to hide it with his hands. The hairy bear held up his bun, still tied with white yarn, and laughed, his mouth big enough to swallow a jackrabbit, or a little boy.

Next they filed through a room with lots of shelves. A big, scowling woman slapped a folded blanket onto the counter and pointed to the number printed in black on the corner. “Bee-four-five!” she barked. “Remember that: you’re bee-four-five!” And he saw it everywhere: on his toothbrush, on his underwear, on his socks, shoes, shirts, bedsheets, everywhere he looked all the time: B 4 5 . . . B 4 5 . . . B4 5.

Then they gave them each a name—Billy, Sam, Bob, Jim. Boring bila gaana names that didn’t mean anything. They called him Thomas. Bilii Lizhini wasn’t right anymore. Too long, too hard to pronounce, too full of wonder. “Black Horse.” Too strange. Too something.

They slept in a long room, in bunkbeds. Mr. Melon-Head told them everything in English while Mr. Chee explained it in Navajo:

“You will get up at five o’clock sharp every morning. You will make your beds, you will wash, and then you will report to the cafeteria for breakfast. You will leave the dormitory together, marching in single file. . .”

The first night there was lots of crying. The boy in the bunk below him cried first: “Iwant to go home!” he sobbed. “Why are they doing this to us? Why are they doing this terrible thing?”

Thomas climbed down from his bunk and knelt beside him. “It’s all right,” he whispered. “My grandfather told me that the Earth knows us. Wherever we are, the whole Earth knows the bottom of our feet.” He began singing one of the songs of his grandfather. As his voice traveled down the bar racks, the sniffling and whimpering gradually faded away. He sang for an hour, maybe longer, until the younger boys had all fallen asleep and a peaceful silence filled the room.

***

Moasi-A-kha-A-chin-Than-zie-Be-la-sana-Ba-goshi-A-woh. Cat-Oil-Nose-Tur key-Apple-Cow-Tooth.

He recognized them right off: white shirts, dark pants, Sunday shoes, bristly hair, TV smiles—always smiling, as if they were permanently posing for a picture, “Say cheese, please!” And so young. Kids, really. They weren’t government men, Waashindoon, and that was good. They were Gamilii, the Ones-Who-Talk-With-God, which could be even worse.

They were no different from the other do-gooders. Always trying to sell something or other. If it wasn’t gas or flour or life insurance, it was religion. Well, he’d have a little fun with them.

He waited for them to climb out of their baby truck before stepping out of the shadehouse. They ya’at’eehed him, exchanged a hand touch, introduced themselves. The older one, Elder Buck, asked about his family, where he was from, how many years he’d been on the mesa. He spoke pretty good Navajo for a bilagaana, but he was just showing off. How many times had he told that joke about his name? I belong to the Deer Clan. My Father’s clan is Buck, my mother’s clan is Doe. . . He reminded Thomas of a used car salesman in Gallup who once tried to sell him a pick-up at twenty-five percent interest.

The other guy was quiet. His smile came slowly and uncertainly. He was a listener maybe, liked to tiptoe his way around until his footing was more secure. He also looked like he didn’t want to be there.

Buck was telling him, in Navajo, that they had a very important message. Had he ever heard of Jesus Christ?

Thomas smiled. Buck had pegged him as an old medicine man who’d never left the mesa. Blue jeans, turquoise bracelet, silver hair tied in a Navajo knot, red headband. He looked the part. He could play it, too, pretend he didn’t speak any English.

“Who is this man you call Jesus Christ?”

Buck’s eyes bubbled as he told about Our Big Brother in Heaven who loves us so much he died for our sins.

Thomas nodded, his brow arching gravely. “Is Big Brother watching?”

Buck looked confused. Dawson smiled to himself, relishing Buck’s frustration.

Thomas asked if he knew tsin bee na’al’eeli to hahadleeh?

Buck wrestled briefly with the words, his neandrethal forehead fur rowing. “Oar … well?” He laughed. “Orwell! Yes, yes. I know him! I read his book. But Jesus Christ is a different kind of Big Brother.”

Thomas was impressed. It took most bilagaanas a lifetime to learn even baby-talk Navajo. Still, his expression remained neutral, showing nothing. He spoke slowly and austerely: “Before you tell me about Jesus Christ, or anything else, I just want to know one thing: Did you come here to take away my children, like the others?”

Buck who understood everything shook his head, “N’daga.” Dawson deciphered only one word, alchini, children, but it was enough. He nodded solemnly, “Aoo.”

Thomas laughed. “You say No, you say Yes. Who do I believe?”

The two young men traded eyes, then answered simultaneously: “Me!”

***

Gah-Dzeh-Bi-so-dih-Dibeh-yazzie-Wol-la-chee-Moasi-Ah-jah-Na-as-tso-si-Ah nah-Tsah-A-woh. Rabbit-Elk-Pig-Lamb-Ant-Cat-Ear-Mouse-Eye-Needle-Tooth.

First they told them, then they showed them everything: how to eat, sleep, walk, talk, look, act, think, live, believe. And they heard it all the time. It’s not right to eat with your fingers. It’s not right to go dirty and not bathe. It’s not right to sleep in your clothes without pyjamas. It’s not good to talk Navajo. It’s not right to be afraid of Skinwalkers and witches and yeibicheeis or to pray to stick figures in the sand. It wasn’t right and they weren’t right; they were wrong. And the bilagaanas were going to fix them.

They called it Education, and they did it to save the Indians.

***

Gloe-ih-A-kha-Gah-Dibeh-yazzie-Be-A-keh-di-glini-Tkin-Dzeh-Gloe-ih. Weasel-Oil-Rabbit-Lamb-Deer-Victor-Ice-Elk-Weasel

“I don’t get it. He’s smart, he’s educated. And the Gospel’s so logical!”

“Logical to us maybe, because we were raised on it.”

“Speak for yourself. I’m a convert.”

“Okay, but western logic. The great Judeo-Christian tradition.”

They were driving home following another late session at Brother Yazzie’s shack on the mesa. This time he had offered them mutton stew and fry bread, which Buck interpreted as a change of heart.

They had sat cross-legged on a mattress on the splintered floor, eating in the light of a kerosene lamp. A woodstove sat dormant in the corner, serving as a temporary storage shelf for a bag of Bluebird flour, a cast-iron skillet, and a bucket of Snow Cap lard. Two Mexican felt paintings covered the north wall, one featuring a high mountain lake, the other an Indian maiden, reclining on a buffalo robe. The south wall was covered with school certificates and family photographs in plastic frames: shy-eyed children, smiling graduates, young men in uniform. One 9×12 featured Brother Yazzie holding a lamb beside his late wife Hazdezbah, a wiry woman with a chin like a saddle horn. She was gripping the metal bars of a walker, her eyes like holes punched in crepe paper.

The meal time conversation had been amiable and innocuous. Then Brother Yazzie set his tin plate aside and began wiping his greasy hands on his Levis. “Hey, I hear you missionaries get a thousand dollars for every person you baptize.”

Buck unfolded his gargantuan legs and leaned forward defensively. “Wait a minute. Where did you hear that? The church doesn’t believe—”

“Relax, John Wayne. I just want you to know, if that’s true, you can baptize me tomorrow!”

“Tomorrow?”

“You bet! As long as I get fifty percent!”

Dawson chuckled; Buck impaled him with his eyes.

Brother Yazzie saw a green light. He was just warming up. “Sure, you can ba’tize my ‘hoo family—kits, grantkits—” He laid on the Navajo accent extra thick, heavy on the glottals, hard on the consonants. “You gimme fifty percent, and I’ll get the ‘hoo chapter house in the water.”

Later, as their Chevy bounced along the dirt road leading back to town, Buck muttered something about throwing their pearls to the swine.

“Swine? I wouldn’t call him—”

“You’re the one to talk! Encouraging him like that! Why didn’t you just stand up and lead cheers?”

Dawson stared at the moon above the mesa. Desert critters scampered across the zone of headlights.

“Maybe he’s just not interested.”

“Of course he’s interested! Do you think it was on accident that he just happens to be Crystal’s grandfather? Do you think it was on accident that Crystal’s mother says she can go on Placement if her grandfather says okay? Do you think we found his house in the middle of nowhere purely on accident?”

Buck’s eyes darted back and forth between Dawson, the road, Dawson, the road.

“Well, do you?”

Dawson sighed wearily. It was almost ten o’clock. They had been driving around non-stop since noon, fruitlessly knocking on the doors of any shacks or hogans they happened to find. He had exactly six hundred and forty-four days remaining on his mission. He wanted to tell his senior companion that this wasn’t the Marines, thank you very much; that people still had their free agency the last he’d heard; that you can’t force the Gospel on people no matter how much you fast and pray.

“I guess my view of the cosmos is a little different from yours,” he said.

***

Dibeh-Tkin-Nash-doie-tso-Ah-jah-Tsah-Moasi-Dzeh. Sheep-Ice-Lion-Ear-Nee dle-Cat-Elk.

The first time they caught him speaking Navajo he got a warning. He was filing through the food line and the kitchen aide had just dropped two sausage links onto his tray. Pointing with his lips, the boy next to him whispered, “What’s that?” Thomas replied: “Lechaa’i bichaan.” Dog turds.

Mrs. Porter who had ears like a jackrabbit snapped her fingers and hissed across the room: “No talking Navajo!”

But the moment her back was turned, Thomas leaned down to his friend and muttered defiantly, “Mail bicheii”—She’s Coyote’s grandfather—not realizing that the one they called Yeitsoh, the Monster Giant, was standing behind him.

The next thing he remembered, fingernails were digging into the back of his neck, and a voice was ringing like a cowbell: “Mrs. Porter! Mrs. Porter! This one’s talking Navajo again!”

Mrs. Porter with the tumbleweed hair waddled across the room, her mouth an iron frown. “So you like talking Navajo, do you? Well, we’ll see about that! Grab hold of him, Dotty!” The Monster Giant pinned his skinny arms behind his back and hauled him out of the cafeteria and into the bathroom. Mrs. Porter squeezed his cheeks until they made a big O. She shoved a bar of soap into his mouth.

“We’ll see how much you like talking Navajo now!”

Thomas stuck out his tongue, resisting, but Mrs. Porter crammed the bar in harder, deeper. She ground it against his gritted teeth, twisting and shoving, back and forth, in and out, until the boy thought he might swallow the bar whole.

“That’s right, that’s right, chew it up good now. Maybe next time you’ll think twice before talking that dirt language. Okay, that’s good. Let him go, Dotty.”

His arms flung out like wings when the Monster Giant released them. Thomas tucked his head into his shoulder, refusing to look the bila gaana woman in the eyes.

“Drink this,” Mrs. Porter said, offering him water in a paper cup.

Thomas gulped eagerly, thinking it would help erase the bitter taste. Instead his mouth began foaming like a dog’s. He grimaced, gagged, pushed the cup away.

“All of it!” Mrs. Porter commanded.

He sipped slowly, wincing, trying not to confess the pain.

“That’s right,” Mrs. Porter said, gently now, like a mother comforting her injured child. “Taste good? Maybe we learned a lesson now, didn’t we? That’s what school’s for, isn’t it, Mrs. Benally? To learn the lessons of life.”

***

Ma-e-Be-le-sana-Ah-losz-Ah-jah-Gloe-ih-Dzeh-Dibeh-yazzie-Ah-jad. Fox-Ap ple-Rice-Ear-Weasel-Elk-Lamb-Leg.

Tuesday, August 4th

I think it must be hell sending your kids away. Hell for the kids too. We promise them flush toilets and swimming pools, but what’s that to a kid who’s never had them before? Shakespeare was wrong: there’s nothing sweet about parting. I’ll never forget the look on Mom’s face when I said goodbye. Dad gave me his manly handshake—”You can turn your life around, son!” Mom gave me a kiss and wiped the imaginary tear from my cheek ten minutes before it even appeared. When I turned to board the plane, she started crying like a baby. I cried, too, but in secret later on. And I’d wanted to leave home so bad I could taste it—not on a mission, just to get away. It’s been four months and I’m still homesick. Still feel like a fish out of water. The language sounds like a string of grunts and glottals, signifying nothing. And the people stare at you like they’re angry all the time. Elder Buck says to take it one day at a time. Sure. Like a jail sentence.

***

Jeha-A-kha-Chindi. Gum-Oil-Devil.

On Sundays he went with his friends to the Catholic church because there was nothing else to do and they always got cookies after. They sat on wooden benches in a rock building, dark and cold like a cave. Cloaked in a grim gown, Father Bob paced up and down the aisles, rustling sheets of paper in one hand, clasping a wooden pointer in the other. And heaven help the poor kid who dozed off under the mumbly-grumbly spell of his long-winded words.

That was the boy’s introduction to formal religion. God. Jesus. And all of the suffering wooden people along the walls made him wonder why anyone would worship a God who looked so pale and skinny and weak and miserable. One thing he would always remember: no one in that church, not even Father Bob, ever looked happy.

***

Moasi-Tlo-chin-A-chin-A-keh-di-glini-Dzeh-Gah-Dibeh-Tkin-Ne-ahs-jah A-chin. Cat-Onion-Nose-Victor-Elk-Rabbit-Sheep-Ice-Owl-Nose.

He had entered the mission field with a profound conviction that the church was the only true escape from poverty, disease, hopelessness: the truth shall make you free. The rez had tested his hypothesis in ways that even the jungle couldn’t. Each dirt yard had a wood pile, a junk pile, and a broken pick-up. Babies having babies. Hangovers for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Peyote drums pounding through the night. So different from back home.

Home. He’d gone from the Marines to the Mission Training Center. Traded one boot camp for another. He was only seventeen when his mother signed the papers. The goon was tapping his foot in the bedroom, waiting for his nightly delights: big lawyer man in a flashy car. It was her one shot at a life of leisure, Caribbean cruises and Wednesday luncheons with the doctors’ wives. Salvation from shelving discount jeans at Target. Her window, his door, closed quietly behind him.

He was almost twenty-two when the missionaries told him they had a very important message from his Father in Heaven. Still woozy from a night of bar hopping, he had invited the clean-cut young men to come in, have a seat, a beer. (No thanks on the beer.)

Reading their book, he had experienced the most incredible thing. Like the feeling you get when a hundred thousand people cheer you towards the end zone, or when you’re utterly in love. He had never been cheered to an end zone, and he certainly had never been in love. But he imagined this is what it must feel like, because nothing else in his life had ever come close.

Later, the missionaries told him it was the reassuring Spirit of Truth.

***

Moasi-A-kha-A-chin-Be-Tkin-A-woh-A-chi-Tlo-chin-Tsah-Yeh-hes-A-chin-Ah tad. Cat-Oil-Nose-Deer-Ice-Tooth-Intestine-Onion-Needle-Itch-Nose-Girl.

They marched everywhere, in single file: to the cafeteria, to the dorm, to class, to the playground, a dirt field with a chicken wire backstop and a jungle gym. In class Mrs. Lynn held up a yellow stick and said, “This is a pencil. Repeat, please.” And they would all repeat, “This is a pencil.” She held up a small pink thing: “This is an eraser. Repeat, please.” And they did. “This is a book. . . . This is a pencil. . . . This is a table. . . . This is a door. . .” Over and over and over again, all day long, ten moons. Summer, fall, winter, spring. Fire, wind, snow, wind, and fire. One day they all boarded the bus for home, but everything had changed forever.

***

“Explain it to me again.”

“All right. Again. He is like the Holy People—the head of the Holy People. We call him God. He is our Father in Heaven.”

“He is the Great Spirit?”

“Yes, He is like the Great Spirit. Except he has a body of flesh and bones like us.”

“Does he bleed like a man?”

“No, He is God. If He could bleed, He could die. He cannot die; He is immortal. ”

“Why do you say that he died for our sins?”

“Jesus Christ died for our sins. He is the Son of God. He came to Earth like a man, and He died for our sins. Then He came back to life after three days. We call it the Resurrection. Because of this, we will all come back to life after we die.”

“Your God killed Death?”

“Yes. He killed Death.”

“Then he is a very powerful God.”

“Yes. Very powerful.”

***

Cha-Ne-ahs-jah-Na-as-tso-si-Dzeh-Maosi-A-kha-Tsin-tliti-A-chin-Klizzie. Hat Owl-Mouse-Elk-Cat-Oil-Match-ke-Nose-Goat.

His first day back his mother was making fry bread in the shade house, just like the day he had left home. He quietly observed her familiar movements as she molded a lump of dough into a white ball, patting it back and forth until it flattened into a tortilla. Pleated skirt, dirty white socks drooping around her ankles, velveteen blouse. She looked the same except for one thing: a thread of gray in her black hair. Just one, but after that every time he looked, they seemed to multiply, like a spider slowly spinning its web.

He thought about Mrs. Lynn, who painted her lips red and smiled like desert flowers and could add and subtract and play the guitar. He spoke English now, and no one else did. He was used to taking showers, but there was no running water. Or toilets. Or books to read or beds to sleep in. He missed the warm water spraying his face and Mrs. Lynn reading stories before and after recess. His grandfather told stories, but he couldn’t read them. Not from a book with pictures.

***

Tsah-Shi-da-Na-as-tso-si-Shush-Dzeh-Gah-Klesh. Needle-Unde-Mouse-Bear Elk-Rabbit-Snake.

***

“I think we can still meet our quota.”

Elder Buck spread peanut butter onto two slices of Wonderbread and smashed them together like cymbals. His jaw dropped, and half of the sandwich disappeaared.

Quota. Dawson hated that word. Quotas meant numbers, bean counting, feathers in some bureaucrat’s cap. You did quotas when you sold cars or manufactured potato chips. Quota was the voice of his father, the suit-and-tie executive. Quota was so many light years removed from Christ’s gospel, he didn’t even want to think about it. Feed the hungry, clothe the poor, visit the widows.

“What quota?”

“Two more baptisms this month. I wrote it in my letter to President Baxter. I really think we can do it. If we give Crystal two discussions this week and one on Saturday, we can still make the August deadline. And Brother Yazzie, he’ll come around.”

“Like I said, what quota?”

“Okay, so maybe quota’s the wrong word. Goal. Call it a goal.”

Dawson spread a thin layer of strawberry jam on a slice of bread.

“You’ve got to have faith, Elder. If I’ve learned anything on my mission, I’ve learned that. You’ve got to set a goal and then do it, whatever it takes. No excuses. Like Nephi. God doesn’t give a commandment unless He provides a way.”

With a paper towel, Dawson wiped the knife clean, like a dipstick. “God’s not the one I’m worried about.”

***

Klizzie-yazzie-Tsah-Ne-ahs-jah-Maosi-Ba-ah-ne-di-tinin-Tlo-chin-No-da-ih Than-zie. Kid-Needle-Owl-Cat-Key-Onion-Ute-Turkey.

The third time the bilagaanas came Hitler was goosestepping across Europe, the Japanese were swarming like locusts all over the South Pacific, and Thomas had just beaten the hell out of a bearded blond giant in the American Legion boxing ring on a sweltering afternoon in Gallup. Ducking between the ropes, he hopped onto the dirt and elbowed his way through the throng of Sunday drunks and soldiers on leave to the private shade of a tarp.

Two men were waiting for him, both in uniform. Khaki shirts and slacks, vertical caps, private’s stripes. One was tall, blond, and rangy; the other short and swarthy. They asked his name; he said, “Yazzie.” They asked if he was Navajo; he said, “Why?” They asked if he wanted to join the United States Marines; his grin twisted wickedly: “Why in hell would I want to do that?”

They said to defend your country; he said, “You mean your country.” They said it was a special assignment: communications. That was all they could tell him. He smirked: “You mean like Top Secret?” They said, “Yes. Top Secret.”

He thought about the twenty bucks he had coming for knocking out the Viking, barely enough to keep him liquored up for a week. He thought about the day he’d heard the news via the Air-That-Tells-A Story: Imperial Empire of Japan . . . Pearl Harbor .. . Day in infamy . . . And he thought about the day after, how his people had come in droves, the line at the recruiter’s table outside the trading post so long you couldn’t see the end of it, teenage boys and old men bearing rusted rifles from a century ago. He thought about that night in the hogan, the way he had barked at his grandfather: “Why do we fight the white man’s war?” He thought about the intense disappointment on his grandfather’s face, and his soft reply: “Is this what they taught you at the boarding school?” And he thought about how incredibly far he had traveled from the Beautyway of life, although he was less than ninety miles from home.

He shrugged. “Sure. Why the hell not?”

***

Shush-Gah-A-hka-A-woh-Lin-Dzeh-Dah-nes-tea-Dibeh. Bear-Rabbit-Oil-Tooth Horse-Elk-Ram-Sheep

“I had a week to go and I was counting the days. Things started happening, weird stuff.

“One day I was in a bamboo thicket when a mortar shell explodes ten feet away. The bamboo shatters like glass. There’s nothing left except me sitting in this big, smoking ring of grass, checking myself for holes. The next morning I’m on my belly, under fire. I’m grabbing the dirt, trying to pull myself right into it because a machine gun’s sweeping across the field, chopping up my buddies. One by one I see their bodies spasm, like mice caught in traps. It’s getting closer, closer, and then it’s my turn. I’m praying like crazy to someone or something. And it stops.

“Something like that gets you thinking. There’s got to be a reason. God must be keeping me alive for something. So how about you? Why did you go on a mission?”

“Truthfully?”

“You asked me to level with you. Your turn.”

“Heritage.”

***

Dah-nes-tsa-Ah-nah-Bi-so-dih-Nash-doie-tso-Wol-la-chee-Tsah-as-zih. Ram Eye-Pig-Lion-Ant-Yucca.

First thing off the bus there was Drill Sargeant Driscoll roaring like a lion, so loud and fast they couldn’t understand half of what he was saying, but it was something like empty-your-pockets-everything-on-the ground-all-of-it-not-tomorrow-not-yesterday-NOW-I-mean-NOW!

Pocketknives, sticks of chewing gum, combs, eagle feathers, bits of turquoise and quartz crystal, quarters, pennies, cigarettes, chewing tobacco. Thomas stealthily palmed his pouch of corn pollen, a farewell gift from his grandfather.

Next the Marine Corps shaved their heads as Driscoll told them they weren’t worth the dirt ants piss on. They gave them each a number, stamped on metal tags they wore around their necks like animals. They filed through a room where a crew-cut man with August sweat dripping from his jowls gave them each the once over, grabbed pants, shirts, socks, et cetera, off of the shelf and slapped them onto the counter.

They slept in bunk beds, rising way before dawn and eating at long tables in the mess hall. All day they marched and drilled and barked, “Yes, sir!” and “No, sir!” and marched some more and drilled some more, and eight weeks later they all agreed on two things: they were glad it was over, and it really hadn’t been that bad: They had all been there before—at the boarding school.

***

“How do you pay for this thing you call sin? Do you give sheep and goats or blankets?”

“No, we don’t pay like that. We pay with our hearts. We pay with our sorrow. ”

“I think sorrow is cheaper than sheep.”

“Then you have not known deep sorrow, my brother.”

“Does your God know sorrow?”

“He lost one-third of his children to an evil man.”

“Then your God indeed knows sorrow. I have lost five children to the boarding school.”

***

Moasi-A-chi-Gah-Ba-goshi-Ah-jad-Dzeh-Dibeh. Cat-Intestines-Rabbit-Cow Lamb-Elk-Sheep.

They were ushered into a room with pendant lights in wire cages. The commanding officer set them at ease. He commended their performance in boot camp and their willingness to serve their country. Then he cleared his raspy throat and told them they had been recruited to develop a secret military code based on the Navajo language.

At first there was dead silence; then a few of them laughed, thinking it was a joke. Others stared in quiet disbelief. Thomas raised his hand.

“Yes, Private?”

He spoke slowly, sarcastically, slurring his words: “While we’re s’posed to be makin’ up dis coat you’re talkin’ ’bout, are we allowt to talk Navajo?”

The officer looked surprised, confused. “Why, yes. Of course. How could you possibly develop the code without using your—”

“Or are they going to wash our mouths out with soap?”

***

Gloe-ih-Be-la-sana-Ah-losz. Weasel-Apple-Rice.

Night was the worst because just when you thought the war had finally exhausted itself, out of a black nowhere they came, howling like coyotes gone mad. They were ghosts, phantoms, the evil chindii, and bullets seemed to pass harmlessly through them. They just kept coming, didn’t care how many fell or how quickly, just kept coming and coming because that was their way. And the whole time your heart was like a bomb exploding over and over and over again.

Then the captain grabs your arm, throws you to the ground, hot young breath hollering in your ear: “Get on the horn! Send reinforcements to quad two-four-zero, I say again, send reinforcements to quad . . . !” As he scrambles to his feet, a machine gun cuts him in two.

It’s your first message in true combat and your mind goes blank. You’ve got five hundred words stashed in your head, but you can’t remember where. You grip the mike and holler into it: “Arizona! Arizona!” Because that’s the signal for code talkers. You remember that much. You also remember Sargeant Driscoll warning you this might happen: stay calm, relax, clear your mind. . . . Relax? Sure. With bullets bouncing off your helmet, sawing your buddies in half. You close your eyes and try to think, focus, concentrate. That’s the real problem, isn’t it? This is a pencil. . . . This is a book. . . . This is a desk. . . .

You see nothing but winter sky.

More voices: “Indio! Get that message the hell through to HQ! We’re dying out here!”

You try again. You close your eyes and try to see the words in your language because that’s how the code works, you say the word in Navajo and the other guy translates it into English. He takes the first letter of each word and strings them together: Dibeh. Sheep. S. Dzeh. Elk. E. Tsah.

Needle. N. Like that. Or there was the other way, where the words were metaphors for the thing: Besh-lo. Iron-fish. Submarine. Ni-ma-si. Potato. Gre nade. Oh-behi. Pick ‘Em Off Sniper. Gini. Hawk. Dive Bomber. Slowly the fog in your head begins to clear, and through the mist you see the silhouettes of animals and objects from your homeland: Klizzie. Goat. Ca-yeilth. Quiver. Shush. Bear. Lha-cha-eh. Dog. Soon the words come automatically: D-ah-Tlo-chin-Dii-Ashih-hi-Tsa-e-donin-ee-Gah-A-kha-Tsin-tliti-Ba-goshi-A woh-Taa-A-la-ih… TO 4th Division FROM CT 18 SEND REINFORCEMENTS. . . Faster than a fast horse, faster than the bullets flying around you.

An instant later you hear from the other end one word: Gahl Rabbit. Roger. Message received. And within minutes that still seem like hours you hear them charging to the rescue. Arms, legs, rifles, helmets. A six foot-six Marine crashing through the jungle. He rams his bayonet into the belly of a Jap, lifts and heaves him aside like a bale of hay.

But it’s not over: You turn, see a skeleton in light brown sprinting through the smoke, bayonet lowered, and an American boy ten feet away twisting to fire but a moment too late: he rolls over, stares blankly at the kaleidscope of black and gray, a fang of blood hanging from his mouth. And the Japanese soldier is still coming, his mouth a giant hole. You tear back the flap on your holster, discharge your .45 without aiming because you can see the silver point of his bayonet coming at you like a star of destruction. He stops, flies backwards as if he’d jerked the reins of a horse galloping full speed. He rolls onto his back beside the dead American.

Later, you will remember two things: A young officer patting you on the back, “Good work, Geronimo! You saved our butt!” And the faces of the blue-eyed boy and the Japanese soldier who killed him, lying side by side, like young lovers. Taking silent inventory, you note how much more you look like the Jap than the American.

You won’t be the only one to think so.

***

Ne-ahs-jah-Cla-gi-aih-Bi-so-dih-Tlo-chin-Klesh-Tkin-A-woh-Yeh-hes-Tlo chin-A-chin. Owl-Pant-Pig-Onion-Snake-Ice-Tooth-Itch-Onion-Nose.

Another late nighter at Brother Yazzie’s. This time Dawson was at the wheel.

“I thought it went well tonight,” Buck said.

“Sure. . . if you like army talk.”

“He asked about Captain Moroni.”

“So you spend the rest of the night talking about Boot Camp?”

“At least we know he’s reading the book. And how was I supposed to know he was in the service?”

“So now you two are all buddy-buddy, semper fi.”

“I’m sorry if you felt left out.”

“I didn’t feel left out.”

“Then why are you acting weird all of a sudden?”

“I’m not acting weird all of a sudden.”

“Half of that’s a true statement.”

“Suddenly you’re Don Rickles?”

They covered the next mile in silence, Dawson grinding his teeth, a nervous habit that manifested itself whenever he wanted to pick a fight.

“Have you ever asked yourself why the church of eternal families is taking kids from their real families and sending them off to live with strangers? I mean, don’t you find that just a little ironic, not to mention hypocritical?”

“No, I don’t find the Indian Placement Program ironic—or hypocritical. Or any other program that was inspired by God.”

“Was is the million dollar word! Was inspired! Placement started when boarding schools were the only game in town.”

“Better a good Mormon home than a government boarding school.” “Right! But now they’ve got day schools. They don’t have to—”

“Sure, like that junkhouse in Nazlini.”

“That’s not the point!”

“Then what is the point?”

“The point is taking Navajo kids from their homes and turning them into book-toting, movie-going bilagaanas! The point is tearing Navajo families apart!”

“We’re not tearing them apart. We’re trying to seal them together— for eternity. They can’t be saved in ignorance.”

“Sometimes I think we’re the ones who are ignorant!”

“And sometimes we have to make sacrifices now to reap the fulness of the blessings later. You’ve seen what their culture’s gotten them. A dirt floor, an outhouse, and a monthly check from Washington. The church is their only hope—”

“The church! You say that as if the church is some person who can wave a magic wand and make everything all better. The church is an institution run by men—”

“Who are inspired by God, Who really can make everything better— if we do His work!

“Look, if Crystal gets baptized and goes on Placement, maybe she’ll go to BYU and marry in the temple. Then her children will be born in the covenant. She could do temple work for her ancestors clear back to the beginning of time! She could be the first link in Malachi’s eternal chain. Isn’t that worth a little homesickness? A temporary separation?”

Dawson rested his forehead on the steering wheel and momentarily let the pick-up guide itself. “Elder, have you ever once in your life not talked like a scripture?”

“We made a sacrifice coming on our mission, but it’s worth it, isn’t it? You wonder sometimes, especially at first. Maybe you’re wondering now. But if you tough it out, thrust in your sickle—”

“I’m nineteen; she’s twelve.”

“The principle’s the same.”

“I just wonder how those Mormon moms in Provo and Salt Lake would feel about shipping their ten-year-olds off to another state. Maybe they wouldn’t be so quick to call it inspiration!”

They coasted around a long, sloping curve flanked on one side by a whale-shaped rock. Near the shoulder, a flock of crows was feasting on the innards of a side-swiped cow. Buck spoke softly, gently, as if he were trying to calm a spooked horse.

“Elder, who’s paying for your mission?”

Dawson replied cautiously, smelling a trap. “My dad. Why?”

“That’ s what I thought.”

“Why do I have the sneaking suspicion this is all due to the fact that you’ve got ninety-eight baptisms and you’re going home in two weeks?”

“That’s got nothing to do with it!”

“It’s got everything to do with it! Sure it does! Elder Buck gets one hundred baptisms, which means that Elder Buck is a super missionary, which means that Elder Buck’s calling and election are surely made sure! Never mind that ninety-nine percent of those baptisms were eight- and nine-year-old kids who had no idea what they were getting themselves into.”

“That’s a lie!”

“Count ’em, chief!”

Buck stared at the windshield where the night bugs were committing suicide in spookily stellar patterns. He began mentally connecting them: Orion, the Big Dipper, Sagittarius . . .

“Okay, and why do I have the sneaking suspicion this all has something to do with the fact that while I was risking my butt for my country, you and your chicken pals were waxing your surfboards at Malibu?”

Dawson exploded. He was hyperventilating. “You—you—you don’t know what the hell you’re talking about! You are so far off the mark right now you couldn’t find the bull’s eye if it was painted on your nose!”

“Elder—”

“Don’t call me Elder!”

“Okay. Fine. But just answer me one question: what gives you the right to deny Crystal or anyone else the blessings of eternity?”

***

“I still do not understand.”

“That is because I did not explain it well the first time. Sin is when we destroy harmony between God and man.”

“That is not good to destroy harmony with the Holy People.”

“No, that is not good.”

“Is this why you must be put under water?”

“Yes. We are baptized to restore harmony with God. We promise God we will live in peace and beauty always.”

“And what happens if we destroy harmony after we go under the water?”

“That is why we have a Savior. We call Him Jesus Christ.”

***

Klizzie-Tse-gah-A-kha-Dibeh-A-woh-Klesh. Goat-Hair-Oil-Sheep-Tooth-Snake.

The night after Brother Yazzie’s sixth missionary discussion, Jacob Hamblin appeared to Elder Dawson in a dream. He had just stepped out of the shower and was hooking a towel around his waist when the bearded frontiersman materialized. He spoke kindly but firmly: “You’re doing it all wrong, Elder.”

“Doing what wrong?”

“This.” He reached up and made a sharp pulling motion with his fisted hand.

Dawson shook his head, tongue-tied. “I don’t. . . understand.”

“Of course you don’t. You speak it but you don’t think it yet. You’ve got to feel it first—here.” He tapped his fist against his chest.

Suspecting the midnight visitor might be an evil spirit, Dawson raised his right arm to the square, to command him to get lost.

Brother Jacob ripped the towel from Dawson’s body. “Don’t trifle with me, son.”

Dawson covered himself with both hands, like a soccer player defending against a goal kick.

“The way you feel right now, that’s how they feel—that’s how they’ve been feeling for a hundred and fifty years.”

Dawson tried to square his shoulders, stand tall.

“You still don’t get it, do you?” Brother Jacob plucked a six-shooter out of the air, aimed it at Dawson’s crossed hands, and cocked the hammer.

“I get it,” Dawson said.

Brother Hamblin lowered the pistol. “Just remember. It’s their book—Mannaseh. Ephraim can read it too, or whoever else, but it’s written to them. We’re just playing piggy back. You understand?”

Dawson nodded stiffly.

“Is that a yes?”

“Yes, sir.”

***

Klizzie-Dah-nes-tsa-Be-la-sana-D-ah-Tkin-A-woh-Shi-da-Be~Ah-jah. Goat-Ram Apple-Tea-Ice-Tooth-Uncle-Deer-Ear.

He was sitting on the dirt floor watching as the snow slowly buried his mother’s hogan. She called to him from the other side of the woodstove: “Shiyaazh? What’s the matter, my son? What’s troubling you?”

He shrugged, muttered. He had been home for over a year and still nothing. He had even gone to the boarding school where a bearded Paul Bunyan scrutinized his application. “Sorry. I’d like to help you out, but I don’t have a thing.” Turning, Thomas had noticed a smile hatching in the dirty nest on Paul Bunyan’s face. “Now if the janitor quits on me … ” Slipping his hand inside his shirt, Thomas had felt for holes. Found a scar. Old, oozing. That he was in uniform had only salted the wound.

“It hurts me to see you this way,” his mother lamented. “It is not good for you.” The winter-stripped cottonwoods looked like old women in mourning; the wind was their voices wailing for the dead. He closed his eyes.

It started as a distant purr that seemed to brush against him seductively, like a lover’s caress. As it gained volume, he realized it was not the gentle sound of female rain, but the crazed voice of war. He watched as their banner crowned the snow dunes: a big blood stain on a white field. It was followed by a plague of giant insects in black boots and khaki, bayonets and sabers flashing. Angry holes emitted a terrible word: Banzai! Banzai! Banzai!

He heard his grandfather calling from the shadehouse where winter had suddenly vanished. The old man staggered outside, waving his black felt hat at the sheep moving all too slowly towards the corral.

Then bugles and thunder. Bluecoats on horseback gained the ridge, angling towards a point midway between the corral and the attackers. Thomas’s heart soared at the sight of the stars and stripes rippling at the forefront. Fist clenched, shaking it: “Get ’em! Get the bastards!”

But the two swarms didn’t collide in a frenzied mix of smoke and blood. Rather, it was a beautifully choreographed blend of tan and blue that rolled like a great wave towards the corral.

He heard the first shot, saw the red dot blossom into a bloody sun. His grandfather waved his arms desperately: “Why are you doing this? Why are you killing my children? Why are you doing this terrible thing?”

***

Tkin-A-chin-Than-zie-Dzeh-Gah-Bi-so-dih-Dah-nes-tsa-Ah-jah-D-ah-Ah-nah Ah-losz. Ice-Nose-Turkey-Elk-Rabbit-Pig-Ram-Ear-Tea-Eye-Rice.

Sometime after midnight Elder Buck was awakened by a persistent scratching at the door. Cracking it, he was surprised to see the little town sleeping under a blanket of snow.

I’m dreaming, he thought, reminding himself to write everything down as soon as he woke up: his patriarchal blessing had promised that, if he kept himself unspotted, he would interpret dreams even as Joseph of Egypt.

This one was easy: the white field ready for harvest. God’s lost children waiting for the Gospel. He simply had to thrust in the sickle of sweat, faith, and perseverance.

A red spot appeared in the middle of the field, quickly spreading into a circle: the Lamanite rose blossoming.

But not so fast. The smooth surface began to buckle. Cracks appeared as it split into multiple, fluttering parts.

Chickens, he thought, amused at first. Little white ones. Millions. It reminded him of those PBS specials where a pink savannah suddenly transforms into flamingos in flight.

But the fluttering grew frantic as a dark shadow stretched across the valley like an alien invader. Looking up, Buck was relieved to see that the eclipsing agent was a giant hand swooping down to scoop up the birds.

He smiled. Fear not, little flock. How often have I come down to gather you up as a hen gathereth her chickens, but ye would not. . .

The rose became liquid, bubbling. A fountain of blood.

Then he heard the first of many screams, not human, but not animal either. Certainly not a chicken sound. He watched in horror as the thumb and forefinger of the condescending hand pinched a chicken’s body until its head popped like a pimple. It pinched another, squeezed, and another. A screaming snow-flurry filled the screen in Buck’s head as the hand continued reaching, squeezing, popping.

Buck grabbed a shovel and charged the murdering hand. He buried the blade between the thumb and forefinger. As he withdrew the blade, a slit appeared. It slowly widened into a mouth which spoke: “Forgive him, Father, he doesn’t have a clue.”

The next morning Buck cut himself shaving five times.

***

Dibeh-Dzeh-Ah-jah-Gah-Sheep-Elk-Ear-Rabbit.

His last trip to the city he was standing alone outside Wal-Mart waiting for his daughter. He thought he must look like one of those wooden Indians he used to poke fun at outside the old curio shops on Route 66. Smiling, he closed his eyes and enjoyed the warmth of the sun on his wrinkled face.

It wasn’t long before his peace was broken by the noxious sound of war: loud, pounding words and music without meaning. A pick-up rolled up in front of him, the noise blasting out both windows. The passenger door swung open, and a Navajo boy climbed out. One side of his head was shaved to the skin, the other side was long and droopy. He was wearing baggy blue jeans, like a rodeo clown, and a black t-shirt with a dagger buried in a skull. Two gold pins winked in his nose. He waddled towards the storefront with sunken shoulders, his belly jiggling.

Thomas knew better, but he couldn’t help it. As the boy approached, he spoke to him in Navajo: “Hello, my grandson! Hello! My grandson, I want to ask you a question. Why are you doing these things to yourself? Why are you behaving this way? Do you not respect yourself and your family? Why are you doing these things to your face and your hair and your body?” The boy stared at him strangely. His smile twisted into a smirk, and Thomas realized he didn’t understand a word he had said. Ya’at’eeh maybe. Nothing more.

***

Dibeh-yazzie-Tkin-Klizie-Lin-Than-zie. Lamb-Ice-Goat-Horse-Turkey. Thursday August 25

Today we’re fasting for Brother Yazzie. In Elder Buck’s words, so his heart will be softened, so he’ll John Hancock the papers for Crystal to go on placement. I don’t think “soften” is the right word. Eventually you realize there’s laughter beneath those faces. If their mouths appear to twist downward, I think we can thank history for that. Things taken and never returned.

Elder Buck sees it differently: the Book of Mormon prophecies come true. A degenerate people scourged by the gentiles. Only the Gospel will save them. But just because something has been prophesied, does that give one group the right to harm and humiliate another? The Bible said the Jews would be persecuted? Was that a justification for death camps. We think we corner the market on truth, but the other day as we were leaving Brother Yazzie’s, a rattlesnake coiled up in the doorway. He said something to it in Navajo—softly, as if he were talking to a pet. It uncoiled and slithered away. Don’t tell me that’s the devil at work. There’s got to be something amazing, something deeply good in that. When he speaks Navajo, it sounds like a prayer, even if he’s just calling to his sheep. Elder Buck’s praying for Brother Yazzie to see the light. I’m not sure what I’m praying for, but I think it’s the opposite.

***

“Tell me again about the bread and the water. You pray to your God, then you eat a piece of bread and drink a tiny bit of water, and that is all. Hardly enough to fill even a small child’s belly. I do not understand.”

“The bread and the water are called the sacrament. It is a ceremony, like the Blessingway or the Nightway.”

“You have sacred songs and sandpaintings?”

“We have special prayers, and like your special prayers, every word must be perfect.”

“And this is how you restore harmony, when someone makes a sin?”

“Yes, this is how we restore harmony. Jesus Christ made this possible when he sweat blood for us in the Garden of Gethsemane.”

“Why did he do this thing for us.”

“He did it because He loves us. He did it because He is our older brother.”

“That is a very great thing.”

“Yes. Very great.”

“Because He is our older brother and He loves us.”

“Yes. Because he loves us.”

***

Bi-so-dih-Gah-Ne-ahs-jah-Na-as-tso-si-Tkin-Dibeh-Dzeh. Pig-Rabbit-Owl-Mouse Ice-Sheep-Elk.

Thomas rose from his mattress and limped out to the hill behind his home where he usually said his morning prayers to Talking God. Gazing up at the heavens, he thought about his grandfather, who had been a star gazer. People used to come to him to learn the cause of their ailments, and he would read their answers in the sky. His grandfather used to say the stars were the fires of the Holy People, and he had taught Thomas how to connect them to make pictures, each one telling a story. The pictures were a milky blur now, and he wondered if it was just his old man’s eyes, or were the fires of the Holy People dying, and if so, who could possibly re-light them?

Thomas knelt down as Elder Buck had instructed. He was supposed to ask the Great Spirit if the gamilii book was true. He was supposed to ask if it was all right for Crystal to go away to school and live with a gamilii family. He bowed his head; he closed his eyes. But instead of the bearded white God of the bilagaanas, he saw the sad face of his father the day he returned home from the boarding school. He was passed out in a ditch by the trading post. One hand was pinned beneath his hip, the other was clutching the neck of a brown bottle. His shirt was ripped open, his face was scrunched against the sand, and his eyes were closed forever.

***

Wola-la-chee-A-Tvoh-Ne-ahs-jah-Tsah-Dzeh-Na-as-tso-si-Ah-jah-A-chin-Than zie. Ant-Tooth-Owl-Needle-Elk-Mouse-Ear-Nose-Turkey.

The third night of his fast, Elder Buck couldn’t sleep. Shortly after midnight, he slipped outside, hiked to the top of a nearby butte, and presented his case to God. The evening rain had relaxed the grip of the earth, releasing the scent of wet sagebrush. The scattered lights of town looked like boats anchored in a still harbor.

He knelt down, his knees sinking into the soft clay. He bowed his head but couldn’t bring himself to break the exquisite silence. He knew how to begin—Father in Heaven—but he didn’t know where to go. Should he repent, apologize, plead for faith, hope, patience? Or a miracle?

He gazed down at the little town, wondering how God perceived it from on high. Was it just another collection of lights smeared across the windshield of eternity? Or did He truly know every hair on every head? Did He see drunks kissing the sand, their only treasure the glitter of broken glass on bootlegger hill? Or the old women weaving spider magic on their wooden looms? Or both?

Buck wept: he had wanted to baptize hundreds, thousands. He had thought that if he could just show them the book, read them passages in their language, they too would feel the gospel miracle and the Spirit would spread across the reservation like wildfire. But now it seemed so futile! Hopeless! The kids—the kids were their only hope, and their only hope was to get off the rez, into a good Latter-day Saint home: carpets, Family Home Evening, scripture study. Skateboards and high school proms, Boy Scouts and Superactivities. Structure, discipline, a peek beyond the mesas. Wasn’t that right? Wasn’t it? Didn’t the children of Israel have to wander forty years in the wilderness until the old people all died off, victims of the false traditions of their fathers? Only then could the younger generation, unperverted by the Egyptian fleshpots, move in.

Buck remained on his knees: twice the clouds devoured the moon, sprinkling water on his head. When he opened his eyes, a dark red line divided the mesa from the sky. It widened slowly, like lips parting. An answer, he thought. But it became a lizard tongue, quickly licking up the stars.

***

Dibeh-No-da-ih-Tsah-Moasi-Cha-Wola-la-chee-Klesh-Dzeh-Gah. Sheep-Ute Needle-Cat-Hat-Ant-Snake-Elk-Rabbit.

Thomas turned to the east where a red crack had appeared along the mesa. He sprinkled white corn pollen, first to the east, then to the south, the west, and finally to the north. Stretching his arms to the eastern sky, he thanked the Holy People for the beauty of the Earth, for wood to build a fire, for sheep to clothe and feed his body, for rain to nourish his corn field. He thanked them for the honor of being a warrior and a father and a friend. He thanked them for the good times, memories, the all-night ceremonies and town trips and long winter nights with Hazdezbah. He thanked them for the simple joy of teaching his children how to ride a horse, swing an ax, throw a rope.

It had been years since he had joined the early morning runners on their jaunt east to greet Dawn Boy, and he never saw one these days. But he began trotting down the rugged slope leading towards town. At first his old bones seemed to crack with each footfall, and the rocks bit right through his K-Mart sneakers. Sucking in the smell of after-rain and pre dawn fire, he saw his daughter Verna at age twelve running to meet the rising sun on the final morning of her kinaalda. The voices of the medicine man and his singers were chanting as her buckskin calves moved swiftly through the morning air. She was wearing turquoise and silver jewelry and a velveteen blouse as red as the sky. She was yelling as she ran, her younger brothers and sisters and cousins running along behind. She was yelling to Dawn Boy, to White Shell Woman, to Talking God and the other Holy People. She was yelling to make her voice powerful and run ning to make her body strong; her hair flowing behind her like a black banner, a flag of anything but surrender.

Thomas jogged past the Begay’s hogan where the sheep in the corral stared dumbly at him. A rooster screeched, and another. He continued running, gathering speed, towards the cottonwood trees choking the mouth of the canyon. He cut across the paved highway and headed up a long, barren stretch. He ran boldly now, counting cadence in Navajo: t’aala’i . . . naaki . . . taa . . . dii. . . ashdla . . . He wondered if he would see Elder Buck or Dawson along the way or the Man-Who-Talks-With-God they call Moroni. Anyone. Anyone at all. He would go, lead or follow. His lungs were gasping, but he felt no fatigue; his feet were bleeding, but he felt no pain. He was running, running, running towards a golden notion growing in the sky.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue