Articles/Essays – Volume 05, No. 4

The Last Days of the Coalville Tabernacle

Surely if it be worthwhile troubling ourselves about the works of art of today, of which any amount almost can be done, since we are yet alive, it is worthwhile spending a little care, forethought, and money in preserving the art of bygone ages, of which (woe worth the while!) so little is left, and of which we can never have any more, whatever goodhap the world may attain to.

William Morris, Hopes and Fears for Art (1882)

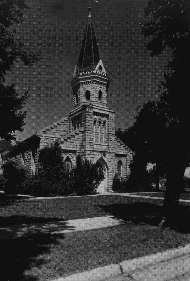

The last time I saw the Coalville Tabernacle it was being decorated for a dance. A cheerful crowd of people, blissfully oblivious to anything incongruous in their actions, were energetically draping a false ceiling of slick plastic strips in the most elegant recreation hall in the Church. Above the uncompleted decor, however, the magnificent original ceiling remained visible, with its ornate cornices and its intricate panels still bright and fresh after decades. We had to climb above the plastic clouds on a tall stepladder to get a clear view of the portraits of early Church leaders. The original portrait of Joseph Smith was not visible at all from the main hall but was concealed behind the stage curtains. The three large stained glass windows were not obscured, though. They were ineptly patched in places but still breathtaking in the oblique light of the winter afternoon sun.

Outside, in the blustery February weather, we walked around the building, admiring the massive stone foundations, wincing at the ugly iron fire escape. Finally, we stood for a time gazing up at the central tower, high above the wooded lot, high above the whole town. Then, reluctantly, we got into the car for the trip home. As we drove away, my eight-year-old son said, “They ought to let the churchhouse alone and tear down the rest of the town instead.”

Coalville is not a handsome town, but neither is it the ramshackle mining camp that its name might suggest. Although coal was important to the area in the nineteenth century, reaching a peak in the 1880’s, there is scarcely any mining activity today, and the community rests on an agricultural base, with a good deal of dairying and livestock raising and some fur breeding in the cool mountain climate. The town is set in meadowlands above Echo Reservoir on the Weber River, but the narrow river valley is bordered by windswept uplands which seem rather harsh and barren when compared to the pastoral charm of Heber Valley to the south and Morgan Valley to the north. Almost everything in Coalville testifies to a long decline in prosperity and vitality. The business houses along Main Street are old and run-down, even more so than in most small Utah towns. The two major remaining public buildings—also old—are the Summit County Courthouse, a stone building with a stubby tower which is situated across the street north of the Tabernacle lot, and the North Summit High School, an added-upon structure on a hill a few blocks to the south. Yet despite—or perhaps because of—the general atmosphere of decay, Coalville is likely to seem homey and comfortable to anyone who grew up in rural Mormon dom, and while it had the Tabernacle standing in dignity at the center of town it was a place of some interest.

The story of the building of the Tabernacle has a familiar ring. A great deal of sacrifice and dedication went into the construction of a meetinghouse in most early Mormon communities, but the edifice that resulted from these labors in Coalville was altogether out of the ordinary. Summit Stake was organized in 1877, taking in much of the high country east of the Salt Lake Valley. In 1879 ground was broken for the Tabernacle, and work went forward for many years under the direction of architect and builder Thomas L. Allen. Although the basic plan of the building was modeled on that of the Assembly Hall on Temple Square, the two structures were quite different in character. The Assembly Hall, tucked up against the wall of Temple Square, seems rather small and unimpressive. The Coalville Tabernacle dominated the community, its 117-foot tower visible miles away. It was originally a single large hall, with the pulpit at the east end and the three large, symbolic stained glass windows (made in Belgium and purchased with the proceeds from Relief Society bazaars) on the south, west, and north. A gallery circled the hall, and above that was the elaborately decorated ceiling, painted and gilded by M. C. Olsen, a Scandinavian immigrant. In every detail, the structure testified to the high level of taste and craftsman ship available in a small town in the nineteenth century, and to the value of beauty and permanence to a people who saw themselves as contributors to the building of the Kingdom of God on earth.

The large hall, built for the era of large Church assemblies, proved unsuitable to changing Church programs, and the Tabernacle was first threatened with destruction in the early 1940’s. A compromise solution was finally reached which preserved the exterior character of the building (except for the addition of a fire escape on the north side) and the ceiling and windows, but which converted the galleried hall into two full levels. On the ground floor were a small chapel and classrooms, on the second floor a recreation hall. Ironically, this remodeling, though it saved the building then, ultimately contributed to the decision to demolish the Tabernacle. Had the great single hall remained, and had it been properly maintained, it could have been incorporated into a new stake center complex without excessive costs. Even in remodeled form, the Tabernacle failed to meet the needs of a two-ward chapel and stake house. The chapel was too small; the classrooms were cramped and few in number; the recreation hall was unsuitable for basketball and too far away from the kitchen (in the basement) for banquets. In 1967, Dialogue warned that “the question of its adequacy for present needs has placed its existence in jeopardy in recent years.”

Until 1970, however, no serious plans to demolish the Tabernacle got beyond the talking stage. Faced with the growing need for new facilities, the stake leadership made tentative plans to build a stake center on “school house hill” in the south-east section of town, but in February, 1970, Church authorities denied permission to proceed with plans for a new building until a decision had been made as to the disposition of the old Tabernacle. During the next several months, stake leaders, under the direction of Pres ident Reed Brown, explored several alternative plans. President Brown has stated that they began their study with every intention of preserving the building in one form or another but were gradually persuaded that no satisfactory solution could be found. Though local leaders may have been sincere in their desire to save the Tabernacle, there is no indication that the Church Building Committee, which was the primary source of expertise for both local and general Church officials throughout these deliberations, was ever very anxious to preserve the building. The Building Committee’s position that the expense of incorporating the Tabernacle into a new stake center complex would be prohibitive has been challenged by other architects who examined the structure. One architect who worked very hard to save the building declared, “Reed Brown and the General Authorities were betrayed by the Building Committee. The people they most naturally relied upon for guidance gave them bad advice.”

In March, 1970, the Coalville Tabernacle was officially listed in the Utah State Register of Historic Sites, and President Reed Brown informed the States Preservation Officer and members of the Utah Heritage Foundation at that time that there was a possibility the building would be torn down. They offered to work with local officials in the attempt to find a solution that would preserve the building, and at President Brown’s invitation a meeting was scheduled for early summer. It was to be a cookout for which President Brown would provide the steaks and at which the Summit Stake leaders, some General Authorities, and preservation officers from the State and the Heritage Foundation could explore possible alternatives to demolition.

“That was when we should have started, back in June,” says an officer of the Heritage Foundation, “but none of us seriously thought the building was in danger. We could no more believe they would tear it down than that they would tear down the Salt Lake Temple. Now,” he adds ruefully, “I’m not even sure that’s safe.” Preservation officials did keep in touch with President Reed Brown by telephone to follow developments. He reported that several possibilities were being considered but refused to identify specific proposals. This began a period—which has not yet ended—of bad communications. Those who could have offered concrete proposals were unaware of what was happening, and as they gradually grew aware they were unable to reach Church leaders with their suggestions. Those who were making the decisions were cut off from the expert advice of any one besides the Church Building Committee, which has almost invariably in recent years preferred building anew to remodeling or adapting. Though it is unlikely that anyone outside the decision-making councils will ever know exactly what ideas were discussed during this period, there is some evidence that after the idea of incorporating the Tabernacle into the new stake center was rejected there were only two serious alternatives to demolition. The possibility of turning the building over to a local political subdivision, either Coalville City or Summit County, was rejected because it would allow the Church no control over the uses to which the structure might be put. (Lingering resentment by Church leaders of the pressures that led to the Heber City Tabernacle’s being disposed of in this manner seems to have been crucial here. Those who talked with Church leaders about saving the Coalville Tabernacle report that again and again they met the comment, “We’re not going to have another Heber City.” It is true that the Heber City Tabernacle—a fine example of pioneer architecture but a far less distinguished building than the Coalville Tabernacle—has been somewhat neglected since it was turned over to the community, but it is very difficult to understand how it would have been better had the building been destroyed.) The other alternative was to preserve the Tabernacle as a museum and Church information center. This was the plan favored by local officials, but it was rejected by the General Authorities because of doubt that a center only forty minutes from Salt Lake City would attract sufficient tourist traffic to justify the maintenance costs.

By October, 1970, Church leaders had made it clear to local officials that the Church would not participate financially in operating more than one building for Summit Stake. The choice available to the stake presidency was either to go on indefinitely using an inadequate building and give up the idea of a new stake center, or to accept the entire financial burden of maintaining the Tabernacle as a museum, or to tear the historic building down. Anxious as they were to operate an up-to-date program and aware of their sharply limited resources, they saw the decision as inevitable: demolish the Tabernacle so that work could go forward on a new stake center.

In retrospect, it seems highly unlikely any outside efforts could have saved the building after this time. President Reed Brown, despite his earlier interest in saving the Tabernacle, was by now convinced beyond a doubt that demolishing it was the right thing to do. Indeed, even while he was trying to preserve the building it is doubtful whether he appreciated its historical or aesthetic significance. The Salt Lake Tribune quoted him as comparing the Tabernacle to a Model T automobile: “They built a fine car then. But you couldn’t classify it as a real good car today. The old Tabernacle was a fine building for its day. That was a different time, with different needs. We must meet the challenge of our day, as our forefathers met the challenge of their day.”

Whether or not opposition could have been effective at this point, there was little of it. A few people in Coalville were concerned, but the majority of active Church members in Summit Stake were willing to go along with the stake presidency’s plans. When the matter was presented to the priesthood of the stake for a sustaining vote in mid-December, not a single dissenting vote was registered, even though several of the men who attended this meeting later became active in efforts to save the building. Outside Summit County, few people knew the Tabernacle was threatened until February, 1971, when the Salt Lake Tribune began extensive coverage of the story. (The press coverage itself is an interesting story. As the controversy grew in intensity, the Salt Lake television stations, including Church owned KSL-TV, provided exposure. The Ogden Standard-Examiner came out editorially in opposition to the demolition. But readers confined to the Deseret News would scarcely have known a controversy existed.)

The first important opposition to the demolition plans came from two Coalville women, Mrs. Bernett Smith and Mrs. Mabel Larsen, respectively Captain and Parliamentarian of the Coalville Camp, Daughters of Utah Pioneers. With the approval of Mrs. Kate B. Carter, the DUP president, they circulated a petition against tearing down the Tabernacle, and within a short time had gathered several hundred signatures, despite President Brown’s demand (or request, depending on who tells the story) that they turn the names over to him, and despite the warnings (or advice) of local bishops against signing. In the face of this mounting opposition, the stake leadership hurried their plans for demolition. Several wedding receptions and other events that had been scheduled for the Tabernacle during March were cancelled, and the decision was made to award the contract for demolition on Friday, February 19th.

By this time, however, opposition had begun to come from many quarters, including the student officers of the University of Utah, who appropriated $1500 for an architectural study of the building. Perhaps the most remarkable event in the entire battle occurred when Thomas R. Blonquist, an attorney retained by a group of Coalville citizens, sought and obtained a temporary restraining order barring demolition on the grounds of Church doctrine. He argued that the Church decision-making process had violated the principle of “common consent,” and that each member of Summit Stake, including those who opposed destruction of the Tabernacle, held a property right in the building. These legal efforts were clearly a play for time, and during the next few days many attempts were made to reach Church leaders with pleas to save the building. The National Park Service officially placed the Tabernacle on the National Register of Historic Places. Several groups attempted to meet with General Authorities, but with little success.

On Monday, February 22nd, a meeting was held on the campus of the University of Utah to explore plans for saving the Tabernacle. Some 300 people were there, including several groups from Summit County, representatives of various organizations interested in historical preservation, and interested private citizens. At this meeting a fund was established and a committee appointed to seek a meeting with the First Presidency of the Church, in an effort to “gain further time for the study of alternate means of saving the building, and to gain a commitment by the Church to the concept of saving the building.” The committee succeeded in obtaining the meeting but not in its other objectives.

On Sunday, February 28th, the day before the date scheduled for a court hearing on the petition to turn the temporary restraining order into a preliminary injunction, the Summit Stake presidency called for a vote by all members of the Stake on the proposition to demolish the Tabernacle, apparently in the attempt to demonstrate that their plan did have the support of the membership. The vote was a straight up-and-down question of accepting or rejecting “the proposed program.” There was no discussion, and the proposition of saving the Tabernacle was not submitted to the vote. The issue, as presented, was either to accept the proposal and allow the Tabernacle to be destroyed or to reject the proposal and abandon plans for new facilities. Nearly eighty-five percent of the members voted to sustain the decision of the stake presidency. “We feel this vote reveals the true feelings of our people,” President Brown declared. “We are not surprised. We’ve known all along.”

The next day, Judge Maurice Harding of the Fourth District Court threw out the temporary restraining order, though with an expression of personal regret, and the last barrier to demolition was down. Groups interested in saving the building began a last-ditch effort to negotiate for its purchase during the “cooling-off period” which President Reed Brown said would interfere before destruction would begin. President Brown set a price of half a million dollars on the building, though its only monetary value to the stake was in its site. While negotiations were still going on, on Wednesday, March 3rd, workers entered the Tabernacle several hours before dawn and began to strip the interior. By noon they had removed the stained glass windows and chopped out some of the portraits from the ceiling. When residents of Coalville awoke to find the destruction in progress, tensions grew so high that the county sheriff kept several deputies and Utah Highway patrol officers on hand to preserve order. Pickets marched in front of the building, some with signs declaring, “They came in the night like thieves,” and others quoting the Doctrine and Covenants: “We have learned by sad experience that it is the nature and disposition of almost all men, as soon as they get a little authority, as they suppose, they will immediately begin to exercise unrighteous dominion.” Other protesters marched on the Church Office Building in Salt Lake City.

At 12:30 p.m., Mark B. Garff, chairman of the Church Building Com mittee, telephoned the Summit County Sheriff and asked him to stop the demolition work, but to do it “as inconspicuously as possible.” Why was it halted? Why was it necessary for the Church headquarters to communicate with local officials through the sheriff? Were the General Authorities having second thoughts about the destruction? Were they displeased at the haste with which the stake presidency had moved? We will probably never have the answers to these questions. President Reed Brown insists that the stake presidency had full authority to proceed as they saw fit. He claims, moreover, that the First Presidency never wavered in their recommendation that the Tabernacle be demolished.

That same day, the First Presidency issued a statement explaining the decision to demolish the building. Although the Coalville Tabernacle was “a grand old building,” they said, it had neither historical nor architectural significance enough to justify the cost of its preservation, since “there was no unusual church history connected with it” and its general plan was similar to that of the Assembly Hall. The following day, the demolition resumed as abruptly as it had ceased the day before and with no explanation for the cessation, and by Friday, March 5th, the building was a pile of rubble. Coalville citizens, in many cases the children or grandchildren of those who labored to build the Tabernacle, discovered that the demolition contractor expected them to pay him for souvenir fragments collected at the site.

Could what happened at Coalville have been prevented? That is a very difficult question to answer, but it is an important question because it is only a matter of time before other historic buildings are threatened in the same way. There have been persistent rumors in Ogden, for instance, that the pioneer Tabernacle there may be torn down as part of the land scaping of the new Ogden Temple. And what will be next—the Tabernacle in Logan, or in Brigham City, or one of the fine old ward meeting houses that are scattered throughout the region?

The Church apparently has no standard policy for the disposition of old buildings, except for the rather vague standards articulated in the First Presidency statement of March 3rd. Those standards, presumably, would save the buildings on Temple Square in Salt Lake City, but would they save the St. George Tabernacle or the fine building in Paris, Idaho? In the absence of any general commitment to the preservation of structures not intimately associated with early Church leaders, and in the face of the aesthetic insensitivity which seems to prevail in the Church Building Committee, perhaps the best present hope lies in local pride. The Church does not compel local leaders to destroy their buildings, though it may, as it did in Coalville, exert financial pressure. Therefore, if a community cared enough it could probably save its historic Church structures. Perhaps the best defense presently available against the “pull-it-down” policy is the attitude expressed recently by a lady in St. George: “If they tried to come in here like they did in Coalville, we’d meet them with an army. We remember the price our parents paid to build these settlements, and we’re not about to let go of the symbols that remind us of our heritage.” In the final analysis, the Coalville Tabernacle fell because not enough people remembered the twenty years of sacrifice and dedication that went into building it, or if they remembered did not care, or if they cared felt somehow compelled to choose between their commitment to that heritage and their commitment to the Church.

Those of us who are “outsiders,” who do not belong to the wards and stakes that have valuable buildings, can do little but attempt to persuade the Church authorities to develop a policy that will encourage preservation of at least the few most important structures, and here is no assurance that this attempt will be successful. Mark B. Garff, the chairman of the Church Building Committee, has suggested that organizations and individuals interested in historical preservation should try to work cooperatively with the Church in raising funds to preserve worthy buildings. President Reed Brown, however, has expressed doubt that the Church would accept money ear marked for specific purposes or that it would surrender even to a limited extent its right to dispose of Church property.

Until some such general commitment to preservation is established, however, the communities that resist the pressure to tear down the old before building the new must expect to pay a price, and it is probably unfair to criticize those who are unwilling to pay the price. Certainly it would have been burdensome for the people of Coalville to bear the whole cost of maintaining and restoring the Tabernacle in addition to their share of the cost of a new building, and that was really the only option presented to them other than to demolish the Tabernacle. And yet, as William Morris wrote nearly a century ago, during a great debate over preservation in England, “I say that if we are not prepared to put up with a little inconvenience in our lifetimes for the sake of preserving a monument of art which will elevate and educate, not only ourselves, but our sons, and our sons’ sons, it is vain and idle for us to talk about art – or education either.”

At this writing, the Tabernacle lot in Coalville has been cleared and the construction of the new stake center delayed for architectural studies to determine whether the old stained glass windows can be incorporated into the new building. Whatever the precise details of the final design, however, there can be no doubt that the people of Summit Stake will soon have a building that is just as modern and efficient as those in dozens of other stakes throughout the Church. It will have another distinct advantage over the old Tabernacle too: no one will object when the time comes to tear it down.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue