Articles/Essays – Volume 28, No. 1

The Law That Brings Life

In writing these thoughts, I am documenting the abandonment of a theological philosophy that has been a central, if somewhat beleaguered, feature of my faith. The decision to abandon the traditions of my heritage was frightening, the transition painful. For most of my adult life I have dutifully followed a practice of a correlated church leadership with feelings of anxiety rather than promised joy of the gospel. The source of my anxiety was the Mormon philosophy that defines God as the expositor of eternal laws; the absolute role of law in our mortal life; and the concept of a tribunal judgement that determines our ultimate destiny in the Mormon eternity. I struggled most with the representation of this philosophy in the programs, policies, and teachings of the church. Though thousands of members continue to have difficulty with the corporate, legalistic theocracy of Mormonism, my own odyssey is somewhat unique in that I ultimately reached a sense of peace in my relationship to the church. However, reaching that peace required coming to a personal understanding of God—a God in many ways different from the divine being of con temporary correlated Mormon doctrine.

I recognize the risk of simplistic generalizations to define a concept as complicated as the nature of God, even the more rational God of Mormon theology. Nevertheless, I would offer that the God I came to recognize through two decades of correlated file leadership is, in addition to being the literal father of our spirits and the architect of our existence, the executor of laws based on eternal truths. Furthermore, it seemed clear in the official literature of the church that God could only be understood within the context of these laws. He alone lives in perfect subjection to and therefore the perfect expression of law. This Mormon doctrine, as represented by Elder Bruce R. McConkie, for example, also teaches that our eternal destiny will be determined in judicial tribunals presided over by God. Based on conditions of immutable justice associated with eternal laws, these tribunals will grant rewards of exaltation to those who have faithfully complied with eternal law, and gradients of punishment will be pronounced upon those who have violated the law without due recompense. It was this concept, this absolute preeminence of law and of a God who exists only within the context of law, that I ultimately had to abandon. In quiet moments of meditation, I had felt the power of divinity settle over me. The peace of those moments belied a God bound by statute and wielding a sword of justice.

I don’t actually remember when God became confusing to me. As a child I thought of God as the kindly, powerful father who could make wonderful things such as the wind, clouds, stars, or lightning and thunder. I was also sure God could give me feathers so I could fly like a pi geon. I often prayed for feathers until it occurred to me that attaining pigeonhood may be a one-way trip, but I never had any doubt that God could make me a pigeon—if he wanted to.

The first I can remember being confused came from hearing a primary lesson about a God who drowned thousands of people and animals. That did not sound like my God. God was supposed to be more like my Bishop Lee. (Actually, he was really Bishop Capener but every one just called him by his first name.) I remember Bishop Lee as a thoughtful farmer with a degree from the University of Utah, and about the only college graduate in our little Mormon town of Riverside, Utah. I remember him conducting sacrament meetings on the steps of the church when summer evenings were too hot to be inside. He reminded long-winded speakers to keep their sacrament meeting talks short so the kids could get to the show at the Main Theater in Garland by 9:15. And folklore has it that he would stop the combines in the fields when the mayfly hatch came on the Madison River in Yellowstone, and the harvesting would wait until the hatch was gone.

I sat one night with Bishop Lee and my father at the old Riverside church and can still distinctly hear him say, “Cats, Ike, if we really knew 10 percent of what we think we know, I guess we’d know 100 percent of what really matters to God anyway.” I was about eight years old at the time, but from then on I would sit in sacrament meetings wondering which 10 percent I should really worry about.

My parents gave me almost total latitude to make decisions and learn from my mistakes. They certainly never gave me even the slightest insinuation that God was keeping a tally so he could punish me for breaking some law, although I am sure there were times they wished he would have taken a more direct hand in my upbringing. Actually, I can really re member only two rules in my house: the cow had to be milked in the morning, and the cow had to be milked at night. Even those rules went away when Dad sold the cow because I went fishing and left him to do the chores. So after about age fourteen I don’t think there were any hard and fast household laws, nor was there any implication that there needed to be laws because God had laws. As for Noah and the thousands of sinners and animals drowned by God, I simply chose to ignore it.

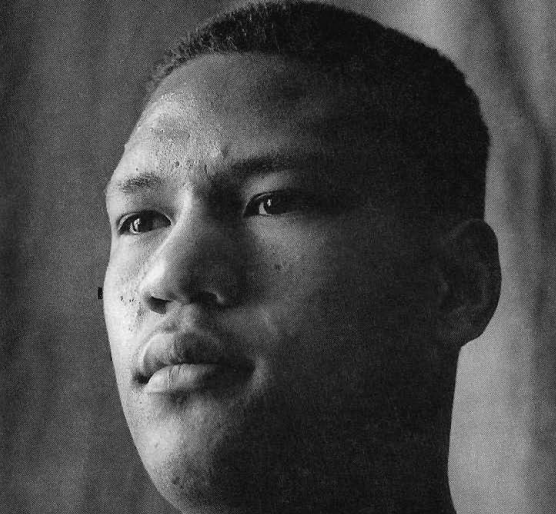

However, being able to ignore what my church taught about God changed when I entered the ninth grade and started formal religious education in Old Testament seminary. There I heard every day about a frightening God. A God who not only drowned people because they did not keep his laws, but used fire to kill priests who disagreed with him. I learned that the Children of Israel were commanded to kill the Canaanites and their gentile neighbors and lived in condemnation for failing to get the job done. I discovered that God was keeping book on me and I was going to be punished for my mistakes, after which I was going to hate myself for eternity. I was taught that he had given the mark of Cain to people he despised because they were not valiant in the pre-existence, a notion that caused me to check my skin carefully every morning. One day I got enough courage to argue with Sister Johns about her portrayal of the nature of God. She got a forced smile, the kind that indicated I was testing her patience, then patiently corrected my misunderstanding. For the rest of the lesson she periodically glared at me just to make sure I did not repeat my indiscretion. In that moment I could sense the distance developing between me and the God I thought about as I lay out at night looking into the expanse of the universe, the God who was supposed to be like Bishop Lee.

This distance initiated a period of anxiety that would continue for the next three decades as I tried to comprehend this official God, my relation ship to him, and how the church really fit into my life. During my high school years I could simply avoid the issues since I seldom thought about God more than the two minutes a day when I prayed, or when some interesting discussion would come up in seminary or Sunday school. No real personal crisis came until all my friends started to go on missions. I would attend their farewells and listen to Coach Simmons or some other distinguished speaker say wonderful things about the soon-to-depart elder. I would watch a tearful girlfriend hang on to her friends and see all the money being collected at the missionary table in the foyer. A part of me longed for my moment to be honored; however, I could not do it. I simply had too many unresolved questions—and no girlfriend to cry for me.

As for the young men who dutifully accepted mission calls, I’m not sure many of them had any particular reason for going other than it seemed like the thing to do. Furthermore, even though most of these de parting elders were really decent guys, there were quite a few who headed into the mission field far less concerned about God’s nature than they were about getting an “all’s well” letter from their girlfriends some time within the first twenty-eight days after their departure. In fact, at the time my friends were accepting their calls, I even had an older returned missionary college friend tell me of an enterprising woman of distinguished sexual profession who reserved Sunday evenings after missionary farewells as special occasions for some of her younger valley clients before they headed into the mission field—though her usual fee was paid as a farewell gift by the friends who had not yet received their calls. One returning elder told me he was convinced the experience had made him a better missionary, though the details of his logic have escaped me. It was something like a final, consummate ritual passage from the passion of carnality to the passion of spirituality—which, in his mind, were closely related.

Fortunately, it seems this rather ribald ritual had passed by the time the guys my age were accepting their calls. However, there was at least one especially memorable farewell that almost didn’t happen because of the joys of the flesh. As the time for prayer meeting arrived, the young elder was not present. A couple of buddies were dispatched to see if he had been in an accident. As the hour of worship arrived, they found him in coitus and completely oblivious to the time or day. In spite of the late start, the honored guest speaker and bishop pronounced him a righteous warrior after the tradition of the Sons of Helaman and bid him an emotional farewell. Friends and family, moved by the spirit, gave generously at the missionary table in the foyer while the young couple spirited away for a few more “never to be forgotten” days before his official departing.

In retrospect, those memories seem like humorous subplots in the moralistic facade that was small town Mormonism of the 1950s—or small town America, for that matter. And yet in spite of the irony surrounding these rather confusing missionary departures, I had a sincere respect for the sacrifice these young men were making—for whatever reasons. By and large, the experience changed their lives—and maybe that’s the most important outcome.

At any rate, while virtually all my high school friends were heading off to spend two years developing a philosophy of institutional religious practice that would, in large measure, govern the rest of their lives, I stayed home. At that point I was really only sure of one thing as it related to my religious future: I could not go on a mission. Then late in my fresh man year of college I met Karen. The following Christmas we were engaged and in the fall before our junior year we were married in the St. George temple. Our marriage has been a choice experience, and even though I did not decide to get married to avoid a mission our marriage did resolve publicly the question of whether I would serve. Karen and I first talked of marriage late one summer evening while sitting on the lawn of the Logan temple. Karen asked what I was going to do about a mission. I remember the feeling of relief I had when I could finally tell someone I had decided not go—it was the first time I had ever said the words out loud. I think I rationalized that God (if he really worried about such things) would be pleased if Karen and I went to the temple, and I assumed he would take away any guilt about my mission decision. Of course, that was a terribly immature hope. God was not going to resolve our relationship just because I checked off another item in the exaltation criteria matrix.

Even though our temple marriage did nothing to fundamentally re solve my questions about God and the church, our early temple experiences turned out to a treasure. Of course, the temple took a little getting used to. Our endowment and sealing had been as bewildering as our first days together were mystifying and clumsy, but we returned to the temple often because of what we felt. At least once a month we went and did a session as soon as we got out of classes and then ate at A and T Ham burgers on the way home. Only years later did I realize that there was a key to the answers I sought in the feelings I was having in the temple.

As long as we were both in school, dutifully involved in our student ward and going to the temple regularly, I really didn’t think about God’s nature very much. My calling was to assist the elder’s quorum president with the adult Aaronic families. I remember the bishop telling me that my job was to touch the hearts of these lost Saints and inspire them to re turn to activity. I have since thought of the incongruity of the statement: “Your job is to touch …” I had a tough time pulling off this soul-touching job without sounding like those synthesized church professionals who draw tears and laughter on demand. Anyway I went and told my families that God wanted them to be active, but I really wasn’t sure. Maybe what God wanted was for them to be kind, charitable people, which many of them were. It even occurred to me that many of the people I was calling to repentance for the sin of inactivity were better people than I was. After a few months of performing my job, I softened my approach and began to feel a warm association with folks who were no longer just assigned families.

It was also during this year in our student ward that I first recognized the self-righteous arrogance that can emerge when church members believe they are acting on absolute divine injunction. A particularly faithful colleague in the elder’s quorum had been “working” with a foreign graduate student to try to interest him and his family in the gospel. After some weeks of encouragement, the man agreed to come to sacrament meeting. On the way to the church with my colleague, there was an accident and the man was killed. He left his wife and small family to fend for themselves in the cultural isolation of Cache Valley. What was particularly saddening for me, however, was the reaction of one of our priest hood leaders. In a subsequent conversation about the accident, he said, “Many would consider this a tragedy, and in a sense it is. But isn’t it a blessing to have the truthfulness of the gospel to comfort us in times like this? To know for a surety that the hand of the Lord has reached out to give this man the opportunity for the blessings of the gospel he would have been denied when he returned to his native land.” I could not imagine a God who would reach down from heaven and cause the pain this family was feeling, and I had difficulty relating to anyone who would callously represent such a God.

I would feel this same frustration many times as with a recent incident when I heard a faithful brother in priesthood meeting commending the hand of God in the AIDS epidemic. Or the high councilman speaking in sacrament meeting acknowledging his gratitude for the testimony he had of the divine plan for God’s chosen people. His sure conviction that the famines and destructions spreading across Africa, the Middle East, and India were the prophesied fulfillment of the Lord’s judgements to cleanse the earth of a wicked and perverse generation. As I returned his self-righteous stare, I could not help but think of the haunting look in the eyes of a beautiful African woman pictured squatting in the dust holding an emaciated child. Eyes that could well have been Mary’s eyes pleading for a clean spot to lay her child, if only to die. This was the judgement of God? But I am getting ahead of myself.

After Karen and I graduated, we moved to Colorado where we started a family. In spite of my continuing misgivings, I got deeply in volved in the church and began serving in positions of priesthood leadership culminating in my call as bishop ten years later. Still terribly immature and without a firm personal theology, I was now the spiritual father of a large, sophisticated ward. In the weeks following my call, I often wondered: if God was uncompromisingly bound to uphold the law, was I—as one of his “chosen servants”—to do the same? Though I faced the issue, I did not resolve it.

In my relationship with church members struggling with problems, I could at times be patient and understanding, though seldom, I suspect, very helpful. In these situations, I sought to emulate the model of men like Bishop Lee and the stake president who had extended my call as bishop. President Claridge was a thoughtful and gentle man who often slipped quietly into ward meetings and never felt obligated to “take the stand” and preside. His counsel was reflective and understanding. How ever, as a new bishop I was reading Elders Bruce R. McConkie, Boyd K. Packer, and Mark E. Peterson. From their writings I learned the role of the uncompromising file leader, and I felt impressed to follow their guidance in my ecclesiastical administration. In the first months after my call we got a new stake president who made sure I knew that the programs and policies of the church were the immutable will of God. We were frequently counselled about God’s expectations regarding 100 percent home teaching, the four-generation program, shadow leadership, correlation meeting, PEC, young men’s presidency meeting, no beards and no long hair at the sacrament table, tithing, building fund, budget, fast offering, temple fund, missionary fund, every member a missionary, sending every son on a mission, temple marriage, monthly temple attendance, priesthood meeting, sacrament meeting, stake conference meeting … I supposed God really expected me to feel guilty when I sat in leadership meetings and listened to the less-than-perfect accounting of my performance. So while at times I could be patient and understanding, like the men whose leadership I deeply respected, at other times I could be dogmatic, demanding, and guilt-ridden.

However, the real crisis of my anxiety did not come because I was a bishop. The crisis came at home. Maybe because I felt guilty about not going on a mission; maybe because I was supposed to be the spiritual father of my ward but had no firm spiritual foundation; maybe because I could not resolve what I really believed about God and my relationship to him; or maybe just because of my immaturity, I decided I was going to have the perfect Mormon family. My children were going to be well-behaved and respectful. They were going to do what I thought they ought to do. And they did—with a price.

It seems almost incomprehensible now. In spite of what I had felt for kind, compassionate men, I could be dogmatic and distant—even with my own family. In spite of my suspicion that God was really a kindly father, I could be impatient like the Old Testament God I learned about in seminary—like the programmed, correlated God characterized by the file leaders of my church. In spite of the example of patient parents who, as my mother had said, “just planted the seeds in the best soil we could find and let them grow,” I worried about what others would think if I did not have the perfect model of a celestial family. Something had to break, and something did. In the spring of 1986—twenty-eight years from the tur moil of Old Testament seminary—I was forced to confront my duplicity. If my family was going to survive the problem I perpetuated, I had to find a personal philosophy to guide the conduct of my life.

My journey of self-discovery took me back through hundreds of memories. Some were distant, others were more recent and vivid. Not long after that difficult spring of 1986, my sons and I were backpacking in a beautiful wilderness area of Colorado. Late one afternoon I found a quiet spot in a grove of aspen trees warmed by the fading summer sun. In the next two hours of meditation, I had a profound affirmation that the precepts I had observed in the lives of men and women I truly respected were the keys to happiness both in mortality and beyond: precepts of honesty, morality, humility, charity, joy, and forgiveness. An undeniable peace filled me as I thought about a life predicated on these precepts. But though I had sought to practice them at times, I was not happy nor was I sharing happiness with those I loved. Far from engaging these precepts on their own merits, I fear I had really become concerned about how others might judge me—of how God might judge me. But were these precepts really aspects of law? Were they valid just because God said they were, or was there something more? Was the purpose of life simply to learn a set of laws God would have us live, to prove ourselves by obedience for its own sake? Did God bless us with happiness just for obediently being humble, moral, charitable, or forgiving? Was God’s ultimate role in our relationship to act as the final arbiter of our failed compliance, our successful recompense? Was the feeling of peace and joy I had felt that afternoon in the mountains an affirmation of law, or was it some thing that transcended law? The more I thought about these questions, the more convinced I became that there was more to life than laws, obedience, and justice. More importantly, I was becoming convinced that our eternal happiness really depended on understanding what it was that transcended law.

That afternoon in the mountains was a transitional point. In the weeks following those hours of contemplation, I began to accept without guilt that I would never understand God, or my relationship to him, on the course of correlated worship I was pursuing. I now undertook what would become an exciting search that included the study of sources as di verse as Bruce R. McConkie, Leonard Arrington, B. H. Roberts, E. E. Erickson, Lowell Bennion, and Dale Morgan. What had started as casual research at the time of my release as bishop now became an obsession. I had to know God and the purpose of my life in a very personal way.

From the thousands of pages of Elder McConkie’s writings, I had come to appreciate a transcendent, though still contradictory, Messiah. Through the historical works of Leonard Arrington and B. H. Roberts, I found our history had a wonderful character and diversity. In their writings I became acquainted with sincere men and women in the early church who struggled as I was, and I learned they were not all wicked apostate enemies of the restoration. From the stimulating works of E. E. Erickson, I discovered a philosophy of ethics that transcended institutionalism and a fraternal theology. Through the eyes of Dale Morgan, I could see myself as an outwardly faithful Mormon might be seen by a thoughtful and informed critic.

Dale Morgan was arguably one of the finest historical researchers of our generation. I had seen references to his work for years, but until I read his biography, writings, and letters I did not know the depth of his passion. Morgan had in mind writing the definitive history of the Mormon church. Although he completed only a few chapters of his history, his research notes are an impressive and expansive personal work of relentless dedication. When he died in 1971, most of his associates were disappointed because his definitive history would never be completed. However, as I read the letters he wrote and the notes he had jotted for himself, I found a piece of the answer I needed, an answer I might never have found in his history.

Dale Morgan was convinced that he could prove Joseph Smith had fabricated the myth that became Mormonism. Through his research, Morgan had found justification for his rejection of the church and its claim of authority. Seemingly more than anything else in his life he wanted to ex pose the myth so clearly and inarguably that no thinking person could doubt his conclusions—though I wonder if his reticence to actually get on with the task didn’t reveal some lingering uncertainty. In any case, he did acknowledge that most Mormons were decent people who were striving, however misguidedly, to live decent lives.

While Morgan’s questions brought me to the crossroads, it was E. E. Erickson’s writings that provided the hope that I could find a meaningful, decent and whole philosophy for my life within my Mormon society. A society that did, in fact, mean much to me. I concluded that I could be true to the spirit of my faith while I sought a theological philosophy that made sense.

From this conclusion, I now approached my personal quest from a very different perspective than Dale Morgan. Whereas Morgan’s search for historical and moral impropriety was a driven intellectual pursuit to understand the pathology of the church, out of the same milieu of history, culture, and theology I sought a philosophy to confirm my faith. I believed I could be successful because of what I had learned from Erick son’s writings: that the philosophy which colors the tapestry of life may be as valuable as the fabric itself. In fact, very possibly the philosophy is the fabric. And if an accepted philosophy colors the fabric with the subtle tones of honesty, morality, and humility; then that philosophy, and its attendant theology—if there be one—is worthy of the bearer. The conduct of my life, which I had played out from a script that often seemed confusing and contradictory, needed a living theological philosophy—not a the ology based solely on the eminence of law, the practice of ritual, and the repetition of doctrinal interpretation.

Another turning point in those transitional months came from a con versation with a friend who is not LDS. We were talking about a common frustration—the frustration of never finding truly satisfying answers to the seminal questions of a transcendent life—a life that spans eternity; how seemingly impossible it is to find those answers that resolve our relationship with the sum of existence and its creator.

In the hours of that discussion, it became clear that my programmed Mormon experience would never resolve the cosmological issues both of us sought to know. This became obvious as I tried to fit the answers of Mormon flannel board theology to the challenging questions my friend was asking. I knew the philosophy I was searching for had to be larger than simply resolving the justification for the conduct of my mortal life within the context of Mormon institutional formalism or society. It had to be larger than just my relationship to my church and the ecclesiastical hierarchy that defined the bounds of my accepted faith. In fact, it became clear that the Mormon institutional theology I had been taught could never reconcile me to the personal God of my childhood. I simply did not want to be reconciled with a God who would kill his children—or command some of his children to kill their brothers and sisters, all in the name of law and justice.

So while my personal search was invigorating and exciting, there were still painful times. I would find myself sitting in testimony meetings listening to people bear witness, with emotion and sincerity, that they knew the church was “true.” I would find myself wondering how could something be known to be true when the people sharing that affirmation each had their own interpretation of what constituted the church, its origins, its teachings, and, more importantly, what constituted truth? Listening to those testimonies, it often sounded as if contemporary Mormon theology might only be an aggregation of personal interpretation couched in a system of communal affirmation. It also troubled me when I considered the many immutable doctrines of the early Restoration that had been rejected by the modern church. It was not enough for me to simply accept that once-true doctrines had been changed by revelation. And the prophet Joseph Smith, revered by faithful members as second only in importance for the salvation of humankind to the Savior himself, could not be called to be a general authority; could not be a bishop; would not be worthy to hold a temple recommend; and, in fact, would be excommunicated if he were to return in the 1980s advocating some of the doctrines and practices of the kingdom he had espoused as the prophet of the Restoration. Doctrines and practices that included plural marriage, good cigars and fine whiskey for special occasions—or not so special occasions—the Lectures on Faith teachings on the nature of the Godhead, the King Follet discourse concept of eternal, uncreated spirits.

At the same time I could not deny the respect I had for the depth of conviction manifested by many Mormon friends and leaders. Even in my moments of deepest doubt I recalled the hundreds of sincere people I had worked with in the church. I thought of the leaders who had trusted me, and I felt a bit of guilt for the violation of confidence my journey of per sonal discovery would imply. I was sure few of them would understand. And if I concluded, as it seemed obvious I would, that striving for perfection within the context of law was not the objective of our mortal experience and the basis of our eternal destiny, I worried about contradicting the general conference theology of my church and its leaders, leaders whom I had sustained as God’s authorized spokesmen, leaders I respected.

But I could not ignore the feeling that I was experiencing something important. The insight from my years of personal research; the experiences in private meditation; the difficult recognition of problems in my family; and my growing resolve to understand my relationship to eternity—all these seemed to be coming together for some purpose. I was, for the first time in my life, finding answers. Answers which first denied the preeminence of law and our absolute subservience to it, and then, most importantly, answers for life. In the process, I was discovering a personal relationship to my Creator and a prospect for life I had not imagined. I discovered a philosophy that invites participation in the experience of living rather than a preoccupation with avoiding the consequences of mortality and fearing the harbinger of justice.

My search had led me, rather more quickly than I expected, to an important conclusion. It seemed to me there is no single reality (or set of realities) that defines the consequence of our existence. Rather, reality is transient. Transient not in terms of what occurred, but transient in terms of interpretation, understanding, and consequence. The reality of any of life’s experiences derives not only from our feelings, our intellectual observations and emotions, but from the influence of that transcendent part of our being that has seen all that has been and all that will ever be. The part of us that Jung has called the God within, or what Mormon theology defines as intelligence—what might be the divinely shared sum of all light and knowledge. Given the endless interplay of each of the dimensions of our being, an ultimate reality cannot exist. The reality of all that has or will occur must change as we are able to see past events with an infinitely maturing insight. This journey, this experiencing of reality rather than finding it, this absolution from the embrace of laws and pre-determined consequence, seems—in my new-found experience—to be the energy of an eternal life.

Those who accept an ultimate reality and final judgement, based on absolute laws, seem to accept that we must all come to a perceptual unity, a point at which there are universal conclusions about every circumstance of life, and every event that has occurred. They would believe that right and wrong are ultimately precisely definable, and for every right there is a fixed and absolute reward; as there is a punishment for every wrong. I find that prospect alien. Alien to the nature of God and the manifestation of God that exists in each one us. If ultimate reality means that we lose, at some point in our existence, the capacity for intellectual, spiritual, and emotional interpretation of all we experience, then we lose the essence of our being. Death would be an eternity of absolute answers; an eternity without continuing the search to understand who we are, how we relate to each other, and what our relationship is to all else comprehensible.

The fact that I had missed the instances where this broader view of an eternal quest is taught in Mormon scripture was probably a consequence of my own myopic scholarship. I have recently been particularly struck by Lehi’s words to Jacob recorded in 2 Nephi 2:11-12.

For it must needs be, that there is an opposition in all things. If not so, … righteousness could not be brought to pass, … neither holiness nor misery, . . . . Wherefore, all things must needs be a compound in one; wherefore, if it should be one body it must needs remain as dead, having no life neither death, nor corruption nor incorruption, happiness nor misery, neither sense nor insensibility. Wherefore, it must needs have been created for a thing of naught; wherefore there would have been not purpose in the ends of its creation.

Some people might justifiably quarrel with my interpretation of Lehi’s philosophy, but I interpret him saying that if we become one body, all existing in absolute congruence without the prospect of diverse perceptions, we are dead. That being the case, then approaching infinite life exists in a state approaching infinite diversities rather than a moment of finite singularity.

As personally intriguing as this concept is, the implication is certainly foreign to our simplistic generalizations of law within the Mormon tradition. If there is no ultimate reality associated with our existence, there can be no absolute truths that define the consequences of our actions as agents/beings. If there are no absolute truths, how can God alone be the final arbiter of law and justice? Yet adherence to law, and the performance of ritual representing those laws, form a central theme in the history of Judeo-Christian theology and its Mormon adaptation.

In the biblical Exodus epoch, Moses ascends Mount Sinai a second time to be instructed by God in the law that is to apply to the Children of Israel. The foundation of that law was embodied in ten absolutes that God inscribed in stone with his finger. These ten commandments, and the almost incomprehensible proliferation of attendant ritual required to demonstrate adherence to them, became the basis of worship for God’s people. In some cases, violation of the law required that a person be put to death. Regardless of the imposed consequence, all of these laws are considered to be the immutable expressions of God’s will. All required absolute, total compliance. Yet even a causal examination of a few of these commandments points out the difficulty of conducting our lives under the premise that these are absolute laws with absolute consequences. Every thinking Christian or child of Israel has struggled with the application of these laws to even the simplest ethical questions of life.

God says that we should not bear false witness, that we should not lie. Yet I can’t remember how many times I have listened to cliched arguments about whether we should be truthful when someone asks our opinion about a truly ugly dress, for example. In addition, there have been a number of interesting amendments to God’s law of bearing false witness. From the time of the translation of the Book of Mormon through the Nauvoo period and into the time of the Reed Smoot senate hearings, the leadership of the church engaged in a practice that became known as “lying for the Lord.” Our leaders used this tactic because they were fear ful that if the truth were known about actual church practice or doctrines their adversaries would destroy the Lord’s work. (This fear seems somewhat mystifying in light of the promise that “no unhallowed hand shall disrupt my work.”) However, we have been assured that the leaders who sought to protect the work by lying will be blessed for their valor. Clearly, lying is not always lying, and justice will not always claim those who bear false witness. Under the rule of law, what constitutes lying must ultimately be determined by some interpretation beyond mortality.

God also says, “Thou shalt not kill.” Yet no sooner had the dust settled on the tablets of the covenant than the Children of Israel were commanded to enter Canaan and kill all the inhabitants. Then for hundreds of years after their return to Israel they were condemned by the Lord for failure to destroy all of the heathens in the Promised Land. As an aside, I have often wondered why the Lord (if he really wanted all these people dead) did not personally destroy the Canaanites, or Laban, for that matter, as he had the pagan priests of the Old Testament. What purpose was filled in directing cousins to kill cousins, nephews to kill uncles, or brothers to kill brothers?

What, then, is the absolute command; the ultimate truth in the law: Thou shalt not kill? Perhaps killing is justified by law when freedom or righteousness is threatened. However, in a complicating modern twist, our church leaders have told us that soldiers who fight for their country, no matter what particular political or military objective a government might have, are absolved of responsibility for killing. During World War II, we had the tragic situation of Mormon soldiers from Germany and Mormon soldiers from England, France, and the United States trying to kill each other—and they were all blameless? Under the mandate of a destiny in law, every instance involving the taking of another human being’s life must be interpreted outside the context of our mortal experience. In a world as complicated as ours, how could anyone possibly know how to act in every situation, even with the guidance of church leaders, or the spirit?

Though I have struggled with the complexities of dozens of cliched ethical problems, no real value is served in reiterating them here.

However, I do have one additional example that has touched close to our family. Mormon doctrine holds that sexual sin is superseded in seriousness only by murder and the sin against the Holy Ghost. Contemporary Mormon teachings define sexual sin as any sexual relationship outside of monogamous marriage. However, even this rather simple generalization does not adequately define what behavior acceptably serves the law. A few years ago some friends had to put their adult daughter in a state institution for the mentally impaired. Prior to admission, the par ents were asked to give permission for their daughter to be sterilized or given birth control drugs. Of course these actions would not prevent patients from becoming physically involved, but they would prevent unfortunate pregnancies. I watched the anguish of these faithful parents as they struggled to know the will of the Lord. If they gave their permission, would they be condoning their child in sin? It was not my position to interfere, but I could not help but wonder how anyone could possibly consider the innocent sexual experimentation of two Down Syndrome adults a sin. In consideration of this instance alone, I knew that something as seemingly obvious as the consequence of sexual conduct required interpretation—an interpretation drawn from the perceptions of intellect, emotion, and spirit. It could not be rendered absolutely right or wrong as a simple consideration of law, and—at times—it even seemed as if God was confused about how we should act sexually.

As I read the history of the dispensations from Adam to Joseph F. Smith, the Lord’s intentions on sexual behavior were anything but clear. At various times multiple spousal and concubinal relationships have been ordained of God for his “elect.” At other times this same God has re quired condemnation and even death for any non-monogamous relationship. Did the ultimate reality change? Did the law change? The longer I struggled to understand the scriptural and contemporary teachings de fining God’s expectations on the appropriate use of the gift of procreation, the more confusing the situation became. Of all of the instances of difficulty I dealt with as a judge in Israel, trying to help others work be yond the issues of sexual “misconduct” were the most vexing. For me personally, the issue I struggled with most was how God could command and expect the practice of polygamy as a condition of exaltation.

Having concluded that endless fretting over seemingly unresolvable situational perplexities was fruitless, the transition to a new philosophy turned out to be easier than I expected. I guess it had always been there, tucked away from the conscious corridor of my mind. The philosophy I found took away much of the anxiety of our existence in an unresolved reality and, at the same time, offered a meaningful context for the law and the conduct of our mortal life. It is a philosophy that has redefined my intellectual and spiritual relationship to God, and, as I came to realize, it has brought a deeper, richer meaning to my life.

I have concluded that we are not created for nor do we live in consequence of laws. Rather, I have come to believe the objective of our existence is to achieve a state of being, in a state of intimacy—intimacy with Deity, with other human beings, and with the totality of creation. I ac knowledge the risk in selecting the term intimacy to describe something as profound as the purpose of life. As my brother Michael has correctly observed, intimacy is one of those New Age terms that has every indication of becoming a pop cliche. However, I needed a term that implied more passion than the casualness we have attached to the designation of friendship. It had to be more concrete than the inexplicable inner expression we associate with love. And, though I like the term unconditional or Christ-like love, the connotation of perfection seems to put it out of the reach of mere mortals. I needed a term to imply the emotional and spiritual intensity one feels for someone or something deeply loved—loved more than self. In my conception, an intimate relationship occurs in those instances when we overcome our fears and insecurities, discard our selfishness and preoccupation with personal gratification, and achieve a singularity of spiritual, intellectual, emotional, and physical oneness—a state of consuming intimacy. To become, as the Savior taught, ” one … as he is one with the father … to become, as one” (John 17:21-22).

In the few moments of my life when I have experienced this intimacy, I have sensed an inner peace and an affirmation that my life could be in congruence with my creator. I have felt that at no other time. I have learned that I needn’t live alienated, fearful of the demands of law and the threat of justice. I have discovered that I feel this peace in those moments when I have forgotten myself, not simply those instances when I begrudgingly put aside something I wanted to do, but in those angstroms of time when I unconditionally gave of myself to another human being. When, for just an instant, I have forgotten I existed as anything but an ex tension of that person and their needs, their hopes, and their fears. I have also felt it when I acknowledged that I am an integral element of the sum of the cosmos, important only in the context of the whole. In those moments, I have understood the meaning of my life, I have touched eternal peace—I have denied submission to law.

Therefore, whereas I cannot comprehend an ultimate reality of ultimate laws and justice meted out against those laws, I am convinced there is an ultimate meaning. I see this meaning supremely manifested in the recorded mortal life of Jesus Christ. As Creator, he had the power to take anything in the world he wanted, but he chose to have nothing of mate rial consequence. As the one person who lived having the power over his own death, he chose instead to sacrifice all that he had in this world—his mortal life and his dignity—to provide a vicarious metaphor for reconciling the human family to an eternal Father. In this sacrifice, he achieved ultimate meaning.

Against this concept of the meaning of life, we can consider sin in a rather different light; a frame of reference that denies that sin is simply the violation of law. I would argue that sin is any action that offends the intimacy of our relationship to another human being, to God, or to the gifts of God’s creation. Sin is also the abuse of the gift of self—physically, intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually. Thus, the consequence of sin is not some punishment defined by an ultimate reality in a tribunal of jus tice. The consequence of sin is isolation, isolation from those we have of fended, including isolation from the ultimate source of our eternal joy and peace, from God Himself. Lehi must have understood this same sense of isolation when he tells his son Jacob that after Satan had fallen from heaven he became miserable forever (2 Ne. 2:18).

If we should leave mortality having never felt the anguish or at tempted to make restitution for the pain we have caused or seen in others, then our destiny is to live in a self-made hell of isolation, or in companionship with others who have lived in thoughtless disdain and selfishness. In consideration of our own conduct, have we selflessly drawn others into our lives or have we been preoccupied with the imposition of our lives, our agenda, or theology on them for personal gratification or public acclamation? Ultimately, we will either find ourselves in companionship with those whom we have drawn into our circle of intimacy or we will be isolated by our unresolved offense. And if, by providence, our circle of our embrace should include an intimate companionship with our creator, we will—through that companion ship—come to know the ultimate meaning of life. As our Savior himself has said, our worthiness to have this reward is—in finality—conditioned on how we have conducted our lives in relation to our fellow human beings. “Inasmuch has you have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me” (Matt. 25:40). Against this backdrop of inclusive selflessness, the conduct of our lives can take on an experiential richness that denies the sterility of the law.

With this much in context, it is left to address the event that forms the keystone of Christian theology: What of Gethsemane and Calvary? Did Christ suffer the pain designated to be inflicted by the divine sword of justice on every one of us sinful, decadent human beings, or was it some thing infinitely more personal? I am assured it was more. In the tortuous hours of his atonement and crucifixion, it was not in surrogate consequence of a divine tribunal that Christ suffered his pain. Rather, Christ became the vicarious memory and conscience of every soul who ever lived. He felt the pain of rejection, loneliness, hunger, and abuse inflicted on every human being (and maybe every creature and sum of his creation) who ever did or will inhabit the earth. His suffering was an act of perfect, complete empathy—of supreme intimacy. He was one with us. In doing what he did, he alone is capable of comforting the victims of life’s injustices. In doing what he did, he alone, having taken stewardship for that pain, can extend forgiveness to those who have caused pain. As for us, we can never take back the suffering we have caused. All we can do is recognize our offense and strive, however ineptly, to make restitution. Our sincere attempts will be acknowledged by his forgiveness as the vi carious steward of that anguish. I cannot envision a more touching, inti mate scene in all of eternity: Christ embracing and comforting the abused, the offended, the tortured, the maimed, the hungry, and the forgotten or comforting the guilt-ridden hearts of those who have strived to make recompense for the pain they have caused. His was not an act of justice served, his was an act of embracing compassion.

However, this is only a part of the story of Gethsemane and Calvary. There is the consequence beyond the reach of his forgiveness and recon ciliation, the pain of isolation that comes as a price for our unresolved offenses against humanity, the dignity of our God, and the gift of his creations. Assuredly this was the most difficult suffering Christ endured. This is the pain of unresolved consequence, the awful isolation that awaits all of us who fail to make restitution for the pain we have caused. For Christ himself, the conscious bearing of this pain must have been compounded by incomprehensible sadness, the sadness of knowing that those of us so resolved would live in an anguish of isolation, never having learned to live expansively in relationships of love and caring, of intimacy. And, in the final hours of his unfathomable despair, Christ was to suffer what, for him, was the ultimate, excruciating agony: the agony of isolation from his Father—the vicarious horror of perdition. “My God, my God—why hast thou forsaken me?” (Matt. 27:46)

The unresolved tragedies of our agency notwithstanding, the great injustice of the Christian experience, and its Mormon derivation, might well be in the denigration of gospel message into a fear-based tradition based upon the sterile doctrines of law, justice, and the threat of retribution. Unfortunately, the preoccupation with this philosophy can and has diverted our attention from the practice of an encompassing divine existence, an experience of divine intimacy. This preoccupation with laws and rules and programs has created a paranoid checklist theology. It has in stilled unnecessary guilt in mere mortals trying to achieve perfection. I wonder if those of us who have distorted the beauty and simplicity of the divine principle of intimacy will not find ourselves in some of the darkest abysses of isolation, there to live in association with others who sought to legislate salvation for their own advantage.

Conversely, exaltation in companionship with our Father is the des tiny of those who find meaning in the experience of their lives, neither hostage to nor sanctified by the law, but glorified for having given life. And what of our journey through the infinite comprehensions of a transient reality? Might that not be the reward of an expansive intellect, an open heart, and an unadulterated spirit—an experience of exalting.

The process that lead me to this moment of consideration, and its attendant conclusions on the meaning of our existence, is not at all clear. Maybe it was an epiphany. Maybe it was a leap of faith drawn from the roots of a subconscious longing for a life based on more than fear and trembling. Maybe it came from an unresolved need. Maybe it was a voice from the bicameral past. Whatever its origins, I have left behind something that felt foreign and have embraced a philosophy that answers much more of who I am, and what I long to be. I have found a philosophy that resonates with the spirit of life.

Most all the pieces now fit—though I still had to resolve my relationship to an institutional theology that embraces the preeminence of law. From my perspective, Mormonism has followed a well-established pat tern of religious institutional formalism. Our origin is found in the radical rejection of dogma in a pattern reminiscent of Christ’s fledgling church in the meridian of time, or Martin Luther in his challenge to institutional Catholicism, or Saint Francis in rejecting the pious arrogance of the powerful Catholic monastic orders. Though early Mormonism seemed to promise a refreshing departure from established evangelical or institutional theological rigidity, the movement quickly grew in structure and organization; an organization that led to statutes; statutes that demanded absolute obedience; obedience that mandated conditions of conformance; conformance that required judgement; and the emergence of guilt for those incapable of meeting the demands of the law. Guilt and fear bred rigidity at the expense of intimacy. Sadly, Mormonism developed a preoccupation with maintaining the imperative of the institutional hierarchy and an institutional imperative that would glorify a God of justice and vengeance.

On the other hand, as I have reflected on the warm, thoughtful ad vice of Elders Sterling W. Sill and Marvin J. Ashton or the good-humored counsel of President Thomas Monson, I have found messages which resonate with a philosophy of life and the nature of a creator I recall as the God of my childhood. At the same time I recognize there are many people who seemingly cannot tolerate the absence of absolutes. Consider how the Children of Israel willingly submitted to the Pharisees, and how totalitarian states frequently arise with broad popular support. Maybe many of us are fearful that we will be unable to temper our actions without laws and the specter of justice, or we simply want someone else to think for us and accept the responsibility for our conformance. For those thus bestowed, contemporary institutional Mormon theology will provide absolute answers. As for me, my own search continues. I have no assurance that the answers I have found are the final answers; in fact, my rejection of an ultimate reality would preclude such a conclusion. How ever, I can now pursue my search with peace of mind in the realization that I have only scratched the surface, and am excited in the prospect of what I am yet to know.

I have also accepted that my anxieties were my own. No one forced me to acknowledge any particular concept of God or his relationship to us. The anxiety I experienced came from my own insecurity and shallow scholarship. The duplicity I endured was my own. I allowed myself to get caught up in the emphasis on church programs that my file leaders advocated as the absolute, divine will of God—the pattern of true, eternal laws. Today, though I still have many unanswered questions, I could accept a mission call and teach of a law that “brings life,” a law of intimate oneness with the source of life. I could share a conviction of principles for living rewarding, fruitful lives: principles of morality, humility, charity, integrity, and joy. I could affirm that living those precepts in a spirit of intimacy will bring happiness. I could tell of the sanctity of temples and what I have felt in private meditation there, of a spiritual companionship associated with the temple experience. I could share concepts of provident living I have learned from King Benjamin and the lessons of Christ’s recorded visit to the Americas. I could tell of a young boy in upstate New York who found simplicity in the midst of a confusion of dogmas. I could share my conviction of someone who took thirty-five years to discover simplicity in the midst of the perplexities of a modern Mormonism.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue