Articles/Essays – Volume 01, No. 4

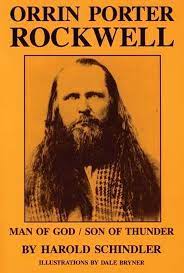

The Legend of Porter Rockwell | Harold Schindler, Orrin Porter Rockwell: Man of God, Son of Thunder

The history of Mormonism and of early Utah as the two merge after 1847 has customarily featured ecclesiastical and political leaders, leaving others who played significant roles on the fighting front of westward expansion to lurk in historical shadows. Among many such neglected men were Stephen Markham, Ephraim Hanks, Howard Egan, and Orrin Porter Rockwell. Of the last much has been written but, like the vines which cover the sturdy tree, legend has entwined itself so intricately in Rockwell literature as to create a challenging enigma. This challenge has been accepted by Harold Schindler in his book, Orrin Porter Rockwell: Man of God, Son of Thunder. The result has been to bring the rugged gun-man more definitely into view but with much of the legendary still clinging to him.

An impressive bibliography reflects thorough research on the part of the author, and absence of discrimination between Mormon and Gentile sources indicates a conscientious effort to be objective. Yet the reader raises an intel lectual eyebrow when confronted with an over-abundance of irresponsible “testimony” and sensationalism represented by such names as William Daniels, Bill Hickman, Joseph H. Jackson, Swartzell, Achilles, Beadle, and more recently, Kelly and Birney’s Holy Murder. The foregoing title and others like “Brigham’s Destroying Angel,” “Crimes and Mysteries of Mormonism,” and “Danite Chief” do not spell objectivity, but perhaps do have a place in reflecting the emotional atmosphere in which Rockwell moved. The author explains it this way: “Whenever possible, I have used primary sources; in some instances it was necessary to consult works considered anti-Mormon. Since an account of Rockwell’s life must be the history of a myth, a folk legend, not less than the history of a man, the possible bias of an authority is in a sense immaterial for such a book as this.” The reader needs to keep this in mind as he runs repeatedly into old charges and accusations to which he feels time has given appropriate burial. He must also keep in mind that the author’s use of “resurrected” scandal does not necessarily indicate his acceptance or rejection of it. On occasion he specifically rejects its validity (pp. 198n., 298).

Nevertheless, after acknowledging the validity of indulging in the use of questionable source material, one is inclined to ask why the author would, for example, prefer a William Daniel’s account of Joseph Smith’s martyrdom with its dramatic embellishments, to any of several other eye-witness accounts including those of John Taylor and Willard Richards. Anti-Mormon testimony is given free rein in relation to the shooting of Governor Boggs, especially in an effort to link Joseph Smith with it through the death “prophecies” which Rockwell tried to fulfill. Evidence of these predictions of Boggs’s early and violent demise unravel into loose ends as the whole affair becomes unfinished business. After an accumulation of anti-Mormon charges convinces one of Rockwell’s guilt, a contrary court decision such as that of Judge Pope (p. 88) throws the whole question back to where it has been for over a century — a state of uncertainty in which each reader decides the case for himself according to his personal prejudices.

The author has organized the materials of his extensive bibliography into a very readable book. However, as he weaves the narrative to serve as a vehicle through which to present the rugged frontiersman, he sometimes dwells to such length upon certain phases of the story that the reader wonders what became of Porter and grows impatient for his return. The lengthy rehearsal of the Missouri phase of Mormon history is supposedly calculated to account for the development of Rockwell’s attitudes and frame of mind, which, in fact, it does accomplish. However, there seems to be less justification for relating the entire Walker War episode of late summer, 1853, even with side issues like the Brigham Young-Jim Bridger rivalry and the Gunnison Massacre, before Rockwell finally becomes identified with it in the peace negotiations the following spring.

There is also a tendency to bring the frontier scout into the picture with questionable justification by speculating where “he might have been.” A case in point is where the author gives Porter priority by inference when the Mormons first entered Salt Lake Valley: “It is likely .. . in his capacity as scout [Rockwell] was the first member of the pioneer group to penetrate the New Zion” (p. 171). It is recorded that he did serve as messenger between Brigham Young and the advance company, but if he preceded Orson Pratt and Erastus Snow into the valley, the records are strangely silent about it. Again, referring to a Mormon opportunity afforded by the failure of McGraw and Hockaday to satisfy their government mail contract, Mr. Schindler states, without reference, that Brigham Young “called in Rockwell to discuss it, for few Mormons knew the plains better” (p. 28). This sounds like the author is finding a place for his subject in a major venture which began with the unsuccessful Great Salt Lake Carrying Company in 1849 and continued through the abortive efforts to launch the Brigham Young Express and Carrying Company in 1856. If Rockwell contributed substantially to its launching (and well he might have) the fact deserves a source reference.

Where the author gives accurate references, he sometimes takes the liberty of adapting the materials to his own narrative. After giving the George W. Bean autobiography as his source, he proceeds to embellish Bean’s account of his visit together with Rockwell to the warlike Utes. Where Bean reports leaving his horse in the care of Rockwell and approaching the Indian camp on foot, the Schindler version has him riding in on horseback until the warriors “pulled the young Mormon from the saddle” (pp. 187-189). It also adds considerably to trie trials suffered by the young man as he stood in the center of the threatening warriors. Dealing with the causes of the Walker War, and referring to the Ivie incident in Springville, the author says “this innocent barter on July 17, 1853, ultimately cost the lives of thirty whites and as many Indians” (p. 203). This comment leaves the mistaken impression that the incident stirred Chief Walker’s anger, with war resulting, while in reality it was only a spark which ignited an already explosive situation.

The foregoing observations are not intended to obscure the positive qualities of Mr. Schindler’s work. Orrin Porter Rockwell: Man of God, Son of Thunder is an enjoyable and informative book. As the subject emerges from the legendary towards reality in the hands of the author the reader is introduced to a facet of history usually skirted in objective writing. The author neither indicts nor clears Rockwell of the dark deeds laid to his charge by the enemies of the Church who insisted that he belonged, or perhaps even headed, an avenging Danite group. That such a group existed in Utah, as it did in reality in Missouri, is in no sense established. But some light is shed on the bitter Mormon-Gentile fringe of Utah history in which the press seemed most willing to participate.

Making a final comment on Rockwell, the author has chosen to be charitable towards his subject and not emphasize the growing rift between him and Brigham Young. The President’s defender, scout, and personal friend became alienated from his chief as liquor claimed him increasingly in his closing years. The book ends typically with divergent press evaluations of the life of the man who defended, in his own way, what he regarded as the Kingdom of God on earth.

Orrin Porter Rockwell: Man of God, Son of Thunder. By Harold Schindler. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1966. Pp. 399.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue