Articles/Essays – Volume 38, No. 2

The Maturing of the Oak: The Dynamics of LDS Growth in Latin America

In 1926 just before leaving Argentina after a six-month mission and few baptisms, Elder Melvin J. Ballard of the Council of the Twelve Apostles drew on natural images to suggest the future growth of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in South America: “The work of the Lord will grow slowly for a time here just as an oak grows slowly from an acorn. It will not shoot up in a day as does the sunflower that grows quickly and then dies. But thousands will join the Church. It will be divided into more than one mission and will be one of the strongest in the Church. . . . The South American Mission will be a power in the Church.”[1]

That prophecy has seen partial fulfillment during the past seventy-five years. From 1925 through the 1960s, the Church struggled with limited growth. However, in the past forty years, the Church in Latin America went from less than 1 percent (.72) of the entire Church to almost 37 percent by January 1, 2004. On the same date, Church membership in Latin America was 69 percent of the total Church outside of the United States and Canada. Apostle Ballard’s prediction that South America would be “a power in the Church” is surely in the process of being fulfilled. The increase in membership in Latin America in the last half of the twentieth century is one of the most momentous events in the Church’s history. Without it, the LDS Church would be very different.

This article provides an overview of the Church’s growth and development in Latin America, including some suggestions about why the Church was late in coming to Latin America, why early growth was slow, and when and why expansion in numbers did occur. LDS growth in this region is part of a much larger reformation of religious belief and practice in Latin America and also a result of changes that occurred within the Church itself. Although I strongly affirm the spiritual and prophetic aspects of the Church’s development, most of this analysis is descriptive and informational in nature.[2]

Beginning

To suggest that the early leaders of the Church regarded the world’s Catholic countries with frustration would be a considerable understatement. Whenever missionaries went to the Latin countries, they always confronted the same phenomenon: a close relationship between the government and the Catholic Church. The by-product of that relationship was secular protection of the Catholic Church’s status with restrictions on any type of non-Catholic religious activities. Lorenzo Snow found this dynamic in Italy in 1850 as did Parley P. Pratt during his mission to Chile in 1851. In Chile non-Catholic services could be legally conducted only by an immigrant population who brought their religion with them; and any type of proselytizing activity, including the seemingly innocent distribution of Bibles, was punishable by time in prison. The nineteenth-century decision of LDS Church leaders to concentrate missionary work in the Protestant countries of Western Europe was an obvious consequence of a distinctive church/state relationship in Latin America and southern Europe. The LDS Church went to Catholic countries only when those restrictions were reduced or lifted.[3]

Three theological beliefs greatly influenced the LDS Church’s introduction and evolution in Latin America. First was the admonition to take the gospel to the entire earth as Christ commanded his apostles just prior to his final descent, “And he said unto them, Go ye into all the world, and preach the gospel to every creature” (Mark 16:15). The modifiers “all” and “every” suggest the comprehensive character that missionary work would assume. The second belief was the revelation Joseph Smith received in October 1830 to send missionaries “into the wilderness among the Lamanites” (D&C 32:2)—meaning the descendants of the Book of Mormon peoples, identified as the indigenous population of the Americas. The promise that this population would “blossom as a rose” (D&C 49:24) suggested significant success among the descendants of Lehi. The commandment to do missionary work with this population was often on the minds of the Church leaders. Until the 1960s, most of the focus of this missionary work has been on Native Americans in the United States. However, Church leaders always recognized that Latin America also had a large population of Indians.[4] The only question was exactly when the Church would expand into Latin America.

Combined with that belief, but occasionally seen as a modifying belief, was the concept of the gathering of the descendants of Israel, more specifically the tribe of Ephraim. The foundation of the doctrine was fundamental in the teachings of Joseph Smith, but non-LDS ideas significantly influenced its interpretation from the turn of the century until the 1950s. Some Church leaders embraced the ideas of two secular movements called British Israelism and Anglo-Saxon Triumphalism.[5] Though there are numerous aspects of these movements, the one generally accepted by some Church leaders was the belief that the population of northern Europe, particularly in the United Kingdom, had a high percentage of the descendants of the lost tribes of Israel, especially Ephraim. Consequently, Church leaders explained early missionary success in England and northern Europe, combined with the failure of missionary work in Southern Europe and Latin America, as the presence or absence of Ephraimites in the two regions.[6] This modification in the concept of the gathering helped to explain the downturn in Church growth during the early twentieth century: Most of the gathering had already occurred and missionaries must seek those few remaining Ephraimites scattered through the world. When they had been gathered, just before the second coming, then Lehi’s descendants would accept the gospel.[7]

Thus, the introduction of the Church into Latin America was influenced by these three doctrines, but more secular reasons also played a role. Brigham Young first sent missionaries into Mexico in 1875 for two reasons, most urgently to find a place where U.S. Mormons, under pressure from the government over polygamy, could settle. The second reason was to establish the Church in Mexico among the indigenous population. By 1885, Mormon colonies had been established in the northern states of Chihuahua and Sonora; in 1879, a small branch was organized in Mexico City. The Church has remained a continuing presence in Mexico, though it experienced serious struggles for many years due to political unrest and internal schism.[8]

The Church’s introduction into Argentina in 1925 was strongly influenced by the concept of gathering Ephraim’s descendants. Interested in sending missionaries to South America, President Heber J. Grant approved Andrew Jenson’s vacation trip throughout the continent in 1923 and asked him to recommend where missionaries should be sent. Jenson, then assistant Church historian, strongly believed in the literal gathering concept and enthusiastically recommended that the Church go to Argen tina, “which was so different to all the other South American Republics which I had visited so far. Buenos Aires is very much like the large cities of Europe, the customs and habits having been copied from European conditions.”[9] He was less impressed with the rest of Latin America, especially countries with a large Indian or African population. In 1925 when a group of German members immigrated to Buenos Aires and wrote to the First Presidency asking for missionaries, Apostle Melvin J. Ballard and Seventies Rey L. Pratt and Rulon S. Wells were sent to open missionary work in Argentina. They arrived on December 6, 1925; but by April 1926, missionaries had moved their efforts from the small German group to the much larger Spanish and Italian-speaking population.

Reinhold Stoof, a German convert who had immigrated to the United States from Germany in 1923 and did not speak Spanish or Italian, was appointed president of the South American Mission in May 1926 and took up residence in Buenos Aires in June 1926. He believed that he had been called to work with German immigrants. In 1928 he realized that the German-speaking population in Argentina was small and dispersed, so he sent missionaries to southern Brazil where large numbers of German immigrants were gathered in colonies. The language of the Church in Brazil remained German until the early 1940s when governmental policy forbade the use of non-Portuguese languages in public meetings, and the mission slowly and painfully converted to a Portuguese-speaking mission.[10]

The influence of the “blood of Ephraim” concept remained so strong, however, that Stoof spent part of his mission report in April general conference in 1936 explaining his theory that some of the lost ten tribes went south and settled in Italy and Spain at the fall of the Roman empire: “There may be some who think that the ideal field of labor in which to find the scattered blood of Israel is in the northern countries. For them it may be a consolation to know that a few centuries after Christ’s birth tribes from the north invaded Spain and Italy, and it may be that their remnants are the ones who today follow the voice of the Good Shepherd.”[11] Such a belief justified teaching Spaniards, Italians, and their descendants in Argentina.

The next period of expansion in Latin America occurred immediately after World War II when missionaries were sent into neighboring Uruguay, Paraguay, and Guatemala, partly because American members were living in these countries. Frederick S. Williams, an early missionary and former mission president in Argentina, had also lived in Uruguay and, in August 1946, suggested sending missionaries to President George Albert Smith. Smith called Williams as the first mission president in 1947. That same year missionaries were sent to Guatemala, partly because of the influence of John O’Donnal, a Mormon working for the U.S. government. By 1960, missionaries had also commenced work in Peru and Chile.[12]

Nineteen-sixty-one was a pivotal year in the history of the Church in Latin America, particularly in South America. As part of a limited pilot program under David O. McKay to have General Authorities live away from Salt Lake City, A. Theodore Tuttle, newly called to the First Council of the Seventy, moved to Montevideo, Uruguay, with oversight for the six missions of South America, much as a General Authority had traditionally overseen all of the European missions, even though each region had its own mission. Part of Tuttle’s plan was to expand the Church throughout the rest of South America, this time focusing on the hitherto neglected natives. Shortly after he left South America in 1965, missionaries had opened the work in all of Spanish-speaking South America. By 1966, the Church had opened missions throughout all of Latin America with the exception of small countries whose population had a high percentage of African descent: French Guiana, Guyana, and Surinam.

The priesthood revelation in June 1978 was another landmark event. By 1980, missionaries were working on the major islands of the Caribbean and the small Afro-nations of South America: the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Jamaica, Trinadad, and Tobago. Except for Haiti and the Dominican Republic, their success rate was much below the rest of Latin America.

Growth and Development

Since 1960 the Church’s numerical growth in Latin America has been phenomenal. By the end of 2002, the total membership of the Church was four million (compared to 45,578 when Tuttle went to Uruguay).[13] A comparison with the rest of the world shows the importance of that growth on the Church as a whole. Of the ten countries with the largest LDS memberships, seven are Latin American; of the top twenty countries, thirteen are in Latin America. What has happened in the last three decades might be considered the beginning of the Latin Americanization of a Church that had been almost exclusively a U.S./northern European church. Because of the large number of members in the United States, North America will continue as the Church’s center for a long time, but its international component has become primarily Latin American. If we project growth based on past patterns, within fifteen years (by 2020), the Church in Latin America will hold more than 50 percent of Church members. (See Table 1.)

[Editor’s Note: For Table 1, see PDF below, p. 86]

The Church’s expansion in Latin America has been fairly consistent since the 1960s, with three periods of particularly significant growth. Two of them were during the mid-sixties and mid-seventies, but the most significant was the six years between 1984 and 1990, during which the Latin American percentage of the Church more than doubled.

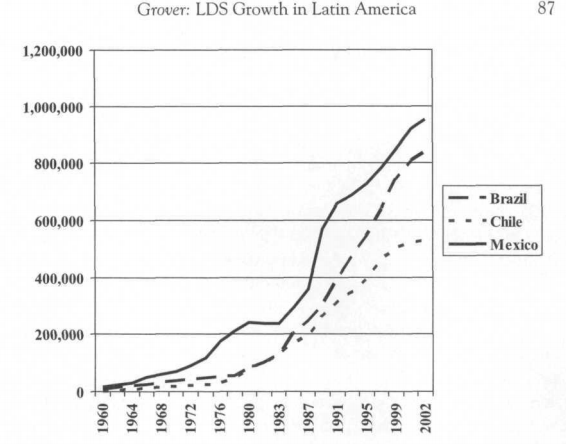

Most Latin American countries were affected by these patterns, but the most significant growth has been in Mexico, Brazil, and Chile. In Mexico, growth occurred through the seventies but accelerated in 1984. Though the expansion slowed in the mid-1990s, it has continued to be strong to the present. Growth in Brazil has been consistent but also accelerated in 1984 and has continued at a high rate to the present. The average percentage of growth in Brazil (15 percent) between 1993 and 2003 was higher than in Mexico (7 percent). If these rates of growth continue, the number of members in Brazil will surpass Mexico about 2005-06. (See Figure 1.) Argentina and Uruguay, which had similar numbers of members through the 1970s, did not experience a similar 1984 surge.

What happened in 1984? An important factor for 1983-88 was that democratic governments replaced military dictatorships (Argentina, 1983; Brazil, 1985; Uruguay, 1985; Chile, 1988), precipitating major economic and social changes. Perhaps more important were psychological changes deriving from the reintroduction of political freedom. The political changes were monumental and without precedent in Latin America, particularly in Brazil and Chile.

Internally, the LDS Church made one of its most significant organizational changes of the century on June 24, 1984, with the creation of thirteen geographical areas, each presided over by an area presidency made up of three General Authorities. This decentralization had numerous effects. The three areas created in Latin America meant that nine General Authorities became residents, coordinating and overseeing missionary work. One result of this attention was a significant increase in convert baptisms.[14]

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 1, see PDF below, p. 87]

What does the future hold? Brazil and Mexico will probably continue to experience significant growth, primarily because of the large base populations. Brazil (172,672,339) and Mexico (100,483,613) are significantly larger in general population and in numbers of Mormons than other countries of Latin America. Even so, the Church in Brazil is still only .5 of 1 percent of the total population and Mexico is just under 1 percent. The only large country in Latin America with a Mormon population larger than 1 percent is Peru.

Furthermore, the general current direction of Church membership is downward, especially in Latin America. (See Figure 2.) This slow-down can be attributed directly to the concerns of President Gordon B. Hinckley and other Church leaders over the low retention rates accompanying elevated baptismal rates. For example, the percentage of growth in Chile dropped from 8.69 percent in 1997 to 1.49 percent in 2002. Visiting Chile in April 1999, President Hinckley delivered a powerful message to missionaries to focus on retention as well as the numbers of baptisms. “The days are past—the days are gone—the days are no longer here when we will baptize hundreds of thousands of people in Chile and then they will drift away from the Church. . . . When you begin to count those who are not active, you are almost driven to tears over the terrible losses we have suffered in this nation. . . . Now, I am sure you have understood my message. I have stated it as plainly as I know how.”[15] As a result, missionaries began to concentrate on reactivation and retention, and the number of baptisms fell. In 2002 when Elder Jeffrey R. Holland of the Quorum of the Twelve was made area president in Chile, attention on retention was accompanied with a consolidation of missions, stakes, and wards. Still, it is important to recognize that, while the rate of growth in Latin America has dropped, it has remained steady across the Church in general at about 2.5 percent a year.

Small vs. Large Countries

Why do Latin America’s smaller countries show a higher percentage of members compared to the general population than the larger countries? The most important factor in baptismal rates is the number of missionaries in each country.[16] Although modified by other considerations, the correlation between growth and number of missionaries is almost always direct. The number of missionaries per country has not been published since the 1970s, so I am unable to adequately test that theory, but we do know the number of missions per country.

Hypothesizing about 150 missionaries per mission allows for a general estimate of the number of missionaries per country. The results show that the larger countries have the smallest number of missionaries per ca pita. For example, Chile in 2001 had eight missions, giving it an estimated 1,200 missionaries or one missionary per 11,808 Chileans. If Brazil had a similar proportion of missions in relation to its population (it actually has one missionary per 44,275 Brazilians), it would have had ninety-seven missions. As of January 2005, it has twenty-six. The countries with the highest percentage of Mormons also have the highest ratio of missionaries per population.

Explaining Growth

Determining the reason for LDS growth in Latin America is a challenge, explained in a variety of ways.[17] Probably any explanation that re lies on a single cause is too simple. LDS growth in Latin America results from several variables, both positive and negative, whose effects yield social, political, and psychological adjustments that, in turn, conduce to religious change. Those changes have been mirrored by internal changes within the Church that attract potential religious converts. I will very briefly suggest several secular occurrences that enhance LDS growth in Latin America. It is important to recognize that I am speaking generally and that there will always be exceptions and variations from this picture.

Though the entire world has experienced phenomenal economic and social changes during the past fifty years, few other regions of the world have experienced the level of change as Latin America. At the end of World War II, Latin America still had important feudal and rural elements, its political system largely traditional and patrimonial, its economy based on exporting raw goods. With industrialization and the modernization of farming came serious disruptions in rural social structures that resulted in major population shifts from the country to the cities. Europe and America experienced similar changes but absorbed them with less disruption than Latin America.

The migrant population in cities formed large poor neighborhoods or slums. With time, education, and capital, the migrants could improve their lives and move into more traditional housing. However, the incoming migrants were so numerous that, even though the slums were transitional, they continued to grow.[18] In their rural setting, these migrants had been connected to traditional social and religious structures, which provided jobs, food, medicine, etc., though often very meagerly. When these people needed help, they had family, a patron, and a church which provided support. In the cities, traditional support systems no longer existed for the most part, and they were often alone, without patrons and extended family. Struggling in the new environment just to get jobs, food, and the basic necessities of life, they regularly turned to organizations that were willing to give assistance, friendship, and spiritual support. Such organizations were often evangelical churches that thrived in the growing neighborhoods.[19]

The LDS Church historically has had limited success with this migrant population.[20] The Church’s success derives from a psychological transformation in society that only begins with the migrant. Historically, most traditional societies, especially Catholic countries, have had such strong connections between religion and culture that cultural identification is also a religious identification. When people say they are Brazilian, for example, they also imply that they are Catholic. Not being a Catholic would be tantamount to rejecting one’s Brazilian-ness. In this cultural environment, changing religion involves more drastic changes than accepting a different set of religious beliefs. It means rejecting one’s family, country, and past. The common statement, “I was born a Catholic and will die a Catholic,” should be heard more as a cultural statement than as a declaration of religious beliefs. Those who leave the Catholic Church are widely considered to be rejecting a history connected as much to nationality and culture as to religious beliefs.[21]

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 2, see PDF below, p. 91]

What has happened in Latin America over the past thirty-five years is the separation of religion from culture and nationality. A change in religion is now more acceptable, an alteration of attitude that began with the migrants to the large urban areas but has expanded to the rest of the society. In an environment that allows the rejection of traditional economic and social practices, the religious foundation that was part of the past and that supported the past becomes less important. When a Latin American seeks to fulfill his or her spiritual needs, the pressure to look to traditional sources is lessened because the relationship between traditional religion and society is less compatible.[22]

I do not wish to overemphasize this separation. The relationship of the Catholic Church and Latin American culture is still strongly felt, and Latin American society contains formidable cultural pressures for its members to remain Catholic. However, in most of Latin America, the fact that between 20 and 30 percent of the people over the past twenty-five years no longer consider themselves Catholic is a remarkable indication of a major psychological shift.[23]

Furthermore, though economic, social, and psychological changes help explain Latin America’s changing religious environment, it is important not to overemphasize secular reasons. For the most part, people make religious decisions, not to meet social or economic needs, but for spiritual reasons. The struggles of life, both secular and spiritual, create a need for contact with and help from a divine source. That desire encourages the search for spiritual assistance. Social disruption creates a larger pool of people susceptible to religious change, but disruption per se does not mean that religious change will occur. All people, regardless of economic class, experience times when they need spiritual assistance; and if they do not find that help in their current institutions and relationships, they may seek it elsewhere. The fastest growing alternative religions in Latin America have a greater emphasis on connection with God than the Catholic Church.[24]

The result of this history in Latin America is a large pool of people susceptible to religious change in a society in which change has been become acceptable and even, in some cases, encouraged. This circumstance alone, however, does not automatically mean LDS growth, for the Church faces significant competition, primarily from Evangelical churches. The competitive religious environment of Latin America today could easily be compared to the competitive religious environment in which Joseph Smith found himself in nineteenth-century New York. In Latin America these religious groups are varied and active. Small churches assemble in the newly growing poor neighborhoods, and crowds of more than 100,000 attend religious revival meetings in soccer stadiums. Though the LDS Church participates in this religious change, it is not even close to being the largest or fastest growing.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 2, see PDF below, p. 93]

Tracking the growth in religions is difficult because of the lack of statistical information on many churches. Some claims of massive growth of religions are not supported by data. It is obvious that alternative religions are growing in both numbers of religions and converts, but determining exact figures is difficult. Only one publication, Operation World, available in book form or on CD, has attempted to keep track of religious growth around the world.[25] Despite questions regarding its accuracy, its figures are probably closer to what is happening than any other available body of statistics. The biggest challenge is that change is happening so fast that there is no way of keeping up. Because Evangelical churches can form at will, hundreds of churches in Latin America are not included in this collection of data.

To gain an appreciation of how the LDS Church compares with other religions, I randomly selected 180 non-Catholic churches in Latin America listed in Operation World and examined growth between 1990 and 2000, then compared their growth to that of the LDS Church. Dur ing that decade, these 180 churches grew 55 percent while the LDS Church grew 63 percent, just 8 percentage points higher. (See Table 2.) The LDS Church had, for example, about the same percentage of growth as the selected religions in Argentina but experienced much higher growth in Paraguay. The lowest percentage of growth of non-Catholic churches in Latin America was in Brazil, but it was still a 35 percent growth over the ten years studied. The LDS Church in Brazil grew almost twice as fast.

I then selected from this sample two churches that scholars often group together: the Jehovah Witnesses and Seventh-day Adventists. The LDS Church grew more slowly than the Jehovah Witnesses but higher than the Seventh-day Adventists. These comparisons show that, even though the LDS Church is growing rapidly in Latin America, its growth resembles that of other non-Catholic churches in the region.

Changes in the LDS Church

The key to understanding LDS growth in Latin America is that internal changes have coincided with external social transformations. As an obvious example, between 1960 and 1980, LDS growth in Brazil, which has a large, racially diverse and racially mixed population, was steady. After 1980, growth took a sharp turn upward, not because of social and political changes in Brazil, but because the priesthood revelation of 1978 tripled the proselyting pool in Brazil. Prior to 1978, the priesthood ban for blacks meant that missionaries proselytized primarily in the south among Europeans and not among the millions of Brazilians who were racially mixed. Very large cities in the north did not have missionaries until after 1980.[26]

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 3, see PDF below, p. 95]

Another very significant event happened a decade earlier, altering the concept of what the Church was to be internationally: the headquarters emphasis on establishing local stakes and temples. The purpose of nineteenth-century missionary work was to baptize converts who would then gather to Utah, thus strengthening the center by drawing from the periphery. In some respects, mission-field wards and branches were always viewed as temporary and transitional. Even after the Church began to dis courage immigration to Utah around the turn of the twentieth century, many members continued to believe that the international Church should not be the same as the Church in “Zion.”[27] This indecisiveness continued into the 1950s for several reasons, including the two world wars. Apostle David O. McKay in his 1920-21 tour of world missions and his presidency over the European Mission (1922-24) had a vision of a strong international church, but it did not come to fruition until after he became Church president in April 1951.[28]

Although missionaries’ primary responsibility has been to proselytize, historically they have been involved in many other activities. Until the late 1950s, missionaries in Latin America participated in all of the activities and responsibilities of the Church organizations. The positive result was that the branches and districts functioned well in terms of activities and record-keeping since the missionaries had time to devote to them. Another positive result was that the missionaries learned how to function in Church leadership positions. However, these organizational responsibilities reduced the amount of time available for proselytizing, resulting in comparatively slow growth.[29]

A less positive result was that local members, especially men, sometimes experienced delays in becoming involved in leadership positions. It often took months before men were ordained to the Aaronic Priesthood and generally much more than a year to be ordained to the Melchizedek Priesthood. Most of the time, members served as assistants to the missionaries, having positions of limited responsibilities.[30] This pattern was generally deemed necessary because of a feeling that new members did not have the experience or training to function well in administrative positions. The result was that American missionaries returned to the United States with valuable leadership experience but the Church in Latin America remained small and its leadership weak.[31]

By the late 1950s and early 1960s under President McKay, the concept had shifted to that of a well-developed international Church with stable organizations. Mission presidents began to focus both on increasing missionaries’ proselytizing time and training members in leadership practices. Most missions had goals for replacing missionaries in branch organizations with members, with the goal of creating stakes, possible only by increased baptisms and properly trained local leaders. In Latin America the result was significant growth in all countries. Branches and districts soon became wards and stakes and a cycle of growth began. The number of missions expanded; and by the 1980s, the organization of the Church in Latin America began to mirror in most ways the Church in Utah, with beautiful chapels, functioning organizations under local leadership, and the construction of temples.[32]

A second important internal factor that affected LDS growth in Latin America was the number of missionaries. In 1950 only 8 percent of all missionaries went to Latin America, resulting in proportionally slow growth. (See Figure 3.)

The example of Uruguay, a small country, is instructive. Formal missionary work began in 1947 when Frederick S. Williams was called as mission president. He sent missionaries throughout the country and established branches in all of the major cities. Uruguay’s capital, Montevideo, had more than 40 percent of the population. The rest of the country was rural, dotted with small cities with populations of about 30,000 or less. Williams sent four to six missionaries into these small cities, creating a significant Mormon presence.

By comparison, in Brazil before the 1980s, missionaries were seldom stationed in cities smaller than 100,000. The LDS presence in Uruguay became important just in terms of numbers of missionaries. For many years, the number of missionaries in Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay was approximately the same (100-30). For several years, Brazil actually had fewer missionaries than Uruguay, resulting in a similar number of baptisms for the three countries. (See Figure 4.) The total number of members did not begin to differ significantly until additional missions were introduced into Brazil (1959) and Argentina (1962), doubling the number of missionaries in those countries.[33]

To show the size of the missionary force in Uruguay, I compared missionary numbers in 1960 with the general population of three other countries. In 1960 the United States had a population of 180 million; Brazil, almost 72 million; Argentina, over 20 million; and Uruguay, 2,531,000. Uruguay had 151 missionaries. If the number of missionaries compared to the general population had been the same for Argentina, Brazil, and the United States, the missionary force would have shown this profile: Argentina (actually 152) would have had 1,230 missionaries; Brazil (actually 273) would have had 4,277; and the United States (actually 3,751) would have had 10,779. The result was that, in a country culturally similar to Argentina, the percentage of baptized members of the Church is the second highest in terms of percentage of Mormons to general population in all of Latin America. Obviously, the most important cause of LDS growth in a country is the number of missionaries.

In short, LDS growth in Latin America is the result of both internal changes in the Church and external factors in Latin America. Social and economic changes, which lessen traditional religious and social controls, create a large pool of potential members. At this point, the Spirit touches those potential members so that they seek out or accept the message of the missionaries.

Retention

Among the challenges related to LDS growth anywhere in the world is retention, an issue that non-LDS scholars of religion have discussed for many years. David Stoll, in the first significant study of non-Catholic religions in Latin America, wondered about the difference between the LDS Church’s published numbers and those who were actually attending meetings. He suggested: “But their phenomenal growth statistics are said to be inflated by competition between Mormon dioceses (called ‘stakes’) and pressures to meet quotas.”[34] Other scholars have not been so kind. I have attended academic meetings in which scholars have suggested outright fraud by the Church in the reporting of statistics. To be fair, these scholars do not appreciate how LDS statistics are collected. The reality is, however, that the number of baptized members in Latin America and those who are active participants differ significantly. It is not possible to determine the exact percentage of active members in a country because attendance statistics are not available. But it is obvious that many converts remain on the Church’s rolls even after they no longer consider themselves to be Mormons.[35]

The LDS Church determines membership differently from most other religions in Latin America because it counts all baptized members who have not been removed from the rolls of the Church, regardless of their level of activity or feeling about the Church. Formal disaffiliation (and name removal) is comparatively difficult and therefore comparatively rare. Members whose whereabouts are unknown are still counted as members of the Church. Naturally, their membership records cannot be as signed to a ward or branch but they are placed in a “Lost Address File” and are still counted as members. I completely agree with the philosophy behind this policy: that the Church still considers itself responsible for finding and fellowshipping these people and/or welcoming them upon their spontaneous return to the Church, even years later; but it does create a mismatch between the records and actual participants. Most other Latin American religions do not have a sophisticated international system of counting; their statistics are generated locally by pastors who identify those who are baptized, attend meetings, or have in some way indicated their preference to be connected to the local units.

Here is a personal example of problems of statistical computation. I know a family in which all five children were baptized members of the LDS Church while in their youth. Four of the children stopped attending as teenagers, married non-LDS partners, were baptized into other churches, and raised their children outside Mormonism. They still occasionally get home teacher visits. Only one has requested that his name be removed. The other three, when approached, asked that their names stay on the rolls. Consequently, in terms of statistics, these three are counted twice, both as LDS members and also in the denominations in which they were subsequently baptized and in which they are currently active. Such are the complications of collecting religious statistics.

A second important point is the difficulty of conversion and religious migration. Baptism is an episode that occurs in a few minutes and does not always mean conversion, which may require scores or even hundreds of changes of attitude, behaviors, beliefs, and understandings. Such a process is frequently long and difficult. It is not unusual for such a conversion to take many years, or even a lifetime. I served my mission in Brazil more than thirty-five years ago and have watched my friends there endeavor to remain in the Church. Many strong members have remained active; but others have experienced an occasional excommunication, sometimes followed by a rebaptism, but sometimes not; joined other churches, lapsed into inactivity, become active again, and so on. Even during periods of inactivity, however, most seem to have positive feelings toward the Church. Most of the time they have considered themselves to be Latter-day Saints. A statistical map of what happens after baptism will show that a certain percentage never attend, some attend for a few weeks or until the missionary who baptized them leaves, some leave after a year, and some remain active. Those who have become inactive often return to activity for a variety of reasons. This pattern of leaving and returning is normal for first-generation members.[36]

Becoming a dedicated member of the Church is a difficult process in Latin America. In the nineteenth century, becoming a Mormon meant physically leaving your home, family, culture, and often country to join with members of the Church from throughout the world, all of whom had gone through the same experiences. Though the pioneer experience was difficult, remaining active in the Church was easier once the convert was in an environment of mostly members. In contrast, converts now join and stay in the same environment, continuing to interact with family and co-workers (some of whom responded antagonistically to the baptism decision) and dealing with lifestyle choices and habits, not all of which are conducive to Church activity. It is difficult to make these changes even when the convert has a strong spiritual commitment, to say nothing of when that commitment is weak.

Third, what is happening in the LDS Church is not unusual. Major churches in Latin America have low attendance, and new converts to evangelicalism often do not stay. In fact, researchers have found that a significant percentage of people do not stop by changing religion once but go on to a third or more, searching for one that satisfies.[37] Nor is Latin America significantly different from other places in the world. The levels of retention and meeting attendance for Mormons in Europe appears to be at about the same level as it is in Latin America; there are just fewer joining the Church. Many countries in Asia have similar problems with retention.[38]

Retention continues to be a problem in Utah as well. In the past twenty-five years, my family and I have lived in three different Utah wards; attendance is still not much higher than 50 percent among a population de scended from pioneers and living where home teachers, family pressure, sometimes employment requirements, and social persuasion all encourage church attendance. According to my stake president several years ago, con vert retention rates in Utah were surprisingly similar to those in Latin America. Many variables are involved, but the bottom line is that conversion to a new religion and continued activity in the Church are not easy.

Spiritual Conversion

Although this paper has focused on statistics and description, it is important to recognize the role of the Spirit in what is happening in Latin America. Most faithful members join the Church because of sacred and life-changing experiences. Here are two examples.

Life was good for Irma Conde, a young lady from Rocha, Uruguay, when she became engaged to a son of one of the wealthier families in the town. Her mother began receiving lessons from the LDS missionaries, but Irma was determined that she would not become involved with a strange new sect. To keep peace in the family, however, finally she yielded to her mother’s insistence that she attend a meeting. Her initial impressions were negative: “The hymns they sang, I didn’t like; the things they taught, I didn’t understand.” She was, however, impressed with the way the members treated her and felt comfortable after the meeting was over. She accepted a copy of the Book of Mormon, believing she would never read it. “I felt I had entered into an unfamiliar and strange world. I didn’t want to think in that way. I didn’t want to feel those things. I didn’t want religion. I didn’t want to know anything about the Church.”[39]

At her mother’s insistence, she sat in on the missionaries’ lessons. One day when the missionaries were planning to visit, she became ill. While her mother had the lesson, they asked Irma to read the Book of Mormon. Without really understanding why, she agreed to do so and discovered that she could not put it down. She read while she ate. When she got tired, she would sleep a little, then continue reading. She was in the book of Alma when the Spirit touched her: “I turned off the light, sat up in my bed, and realized this book could not have been written by a man. It had to be true. I knew nothing about the promise at the end of the book. I had no idea how the Spirit manifested itself. What I felt was something so intense. It was not just a warm feeling in my chest. It was a feeling that enveloped my entire body. From that time forth I knew it was true and I also knew that I would become a member of the Church.”

She was baptized, and her engagement ended as a result, but she has remained faithful. She came to the Church with skepticism and distrust but, after reading the Book of Mormon, was moved to accept its message and the Church.

A second example, also from Uruguay, shows how the spirit of the Lord can touch the hearts even of very young converts. At age four, Rosalina Goitino Ramirez began attending Primary in the Florida Branch with neighbors. Touched by the experience, she began attending other LDS meetings. She has a vivid memory of those early years, especially one experience. Arriving early for church one Sunday, she sat down next to a missionary, Elder Dale E. Miller, currently a member of the Second Quorum of the Seventy. The sun was coming through the window behind him, streaming brightly over his blond hair and seemingly setting it afire. A feeling of comfort and joy settled over this child, which she later recognized as the Spirit. The image of Elder Miller and those feelings of comfort remain vividly with her.[40]

Rosalina went to Primary for the next four years, often alone. She learned to pray and received answers to her childhood prayers. At a very early age, she knew the reality and love of her Father in Heaven. Acceptance and affection from Church members supplemented her testimony. Her friends were not only children her own age but adults who communicated love and respect. While she was still young, her parents divorced, but she found support and help from the members. When she turned eight and asked to be baptized, her father refused to give permission. She waited a full year before he relented. Then her mother forbade her to attend meetings. Again, she persisted in her desires until her mother relented. When she was able to return, the members of the branch extended even greater love.

The Church provided her with the teachings and strength to combat what was happening at home. She learned that she “could be in a bad place and not be bad,” at home, school, or with friends. She accepted the teachings on dress and conduct from her leaders that helped her to maintain high moral standards while friends both in and outside the Church were struggling. When a young man who was investigating the Church asked her to be his girlfriend, she responded that she would date only Church members. After his baptism, they became closer; but when he began talking about marriage, she informed him that she would marry only a returned missionary. This young man, Nestor Curbelo, served in the North Argentine Mission. They married after his return and moved to Buenos Aires where he eventually became the director of the Church’s Seminary and Institutes of Religion in that city.

Their four daughters and son who are of age have married in the temple and are presently active in the Church. Two of Rosalina’s siblings and her mother joined the Church. She has held almost every position a woman can hold in the Church and actively supported her husband during ten years of service as a stake president. The testimony she gained at the tender age of four has resulted in a family being raised faithfully in the Church.

Conclusion

I conclude as I began—with a prophecy. President Gordon B. Hinckley, speaking at a regional conference in Venezuela on August 3, 1999, stated: “Where there are now hundreds of thousands, there will be millions and our people will be recognized for the goodness of their lives and they will be respected and honored and upheld. We shall build meeting houses, more and more of them to accommodate their needs, and we shall build temples in which they may receive their sacred ordinances and extend those blessings to those who have gone beyond the veil of death.”[41]

What has happened in Latin America during the past fifty years is just the beginning of the Church’s growth and development in Latin America.

[1] Quoted in Bryant S. Hinckley, Sermons and Missionary Services of Melvin Joseph Ballard (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1949), 100.

[2] For spiritual aspects of this history, see my “Miracle of the Rose and the Oak in Latin America,” in Out of Obscurity: The Church in the Twentieth Century (no editor listed) (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 138-50, and my BYU Devotional address, “One Convert at a Time” in Brigham Young University 2001-2002 Speeches (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2002), 79-87.

[3] Michael W. Homer, “The Italian Mission, 1850-1867,” Sunstone 7 (May/June 1982): 16-21; A. Delbert Palmer and Mark L Grover, “Hoping to Establish a Presence: Parley P. Pratt’s 1851 Mission to Chile,” BYU Studies 38, no. 4 (1999): 115-38.

[4] See especially Spencer W. Kimball’s addresses. Edward L Kimball and Andrew E. Kimball Jr., Spencer W. Kimball: Twelfth President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1977), 360-63. The best aca demic study is Armand L Mauss, All Abraham’s Children: Changing Mormon Concept of Race and Lineage (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003), esp. chaps. 3, 4, and 5. Chapter 4 discusses the change in emphasis (pp. 114-57).

[5] An example of that acceptance can be seen in Antony W. Ivins’s address, Conference Report, October 1926, 17-19. Ivins, first counselor in the First Presidency, used the ideas of these secular movements to support the LDS doctrine of the gathering.

[6] See Armand L Mauss, “In Search of Ephraim: Traditional Mormon Conceptions of Lineage and Race,” Journal of Mormon History 25 (Spring 1999): 131 -73; Mauss, All Abraham’s Children; and, more generally, Reginald Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism (Cam bridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1981).

[7] W. Grant Bangerter described his mission to Brazil in the early 1940s in just this way: “We thought that the blood of Israel meant blond, European people, and that we wouldn’t expect too much success among Latin peoples because they probably didn’t have the proper lineage. So under these conditions we weren’t too serious about the great overall purpose of missionary work in the Church. And according to our vision, so was our success. We had very little of either.” William Grant Bangerter, Oral History, interviewed by Gordon Irving, Salt Lake City, 1976-77, 7, James H. Moyle Oral History Program, Archives, Family and Church History Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City (hereafter LDS Church Archives).

[8] F. LaMond Tullis, Mormonism in Mexico: The Dynamics of Faith and Culture (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987), chaps. 3-6.

[9] Andrew Jenson, Autobiography of Andrew Jenson, Assistant Historian of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1938), 569; see also Andrew Jenson, Conference Report, April 1923, 78-81.

[10] Mark L Grover, “The Mormon Church and German Immigrants in Southern Brazil: Religion and Language,” Jahrbuch fur Geschichte von Staat, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft: Lateinamerikas (Koln, Germany: Bohlau Verlag Wien, 1989), 295-308.

[11] Reinhold Stoof, Conference Reports, April 1936, 87.

[12] Frederick S. Williams and Frederick G. Williams, From Acorn to Oak Tree: A Personal History of the Establishment and First Quarter Century Development of the South American Missions (Fullerton, Calif.: Et Cetera Graphics, 1987); John Forres O’Donnal, Pioneer in Guatemala: The Personal History of John Forres O’Donnal (Yorba Linda, Calif: Shumway Family History Services, 1997).

[13] I derived these statistics from the annual Church almanacs published since the 1970s, e.g., Deseret Morning News 2005 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 2004); earlier statistics were provided by the LDS Church Archives.

[14] Deseret News Church Almanac 2004, 574-79; Kahlile B. Mehr, “Area Supervision: Administration of the Worldwide Church, 1960-2000,” Journal of Mormon History 27 (Spring 2000): 192-214.

[15] President Hinckley’s address excerpted in “Special Mission Conference,” April 25, 1999; photocopy in my possession.

[16] Gary Shepherd and Gordon Shepherd, Mormon Passage: A Missionary Chronicle (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 10.

[17] See David Martin, Tongues of Fire: The Explosion of Protestantism in Latin America (Oxford, Eng.: B. Blackwell, 1990); David Stoll, Is Latin America Turning Protestant! The Politics of Evangelical Growth (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990); Brian H. Smith, Religious Politics in Latin America, Pentecostal vs. Catholic (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1998).

[18] For this process and the growth of non-Catholic religions in Latin America, see Emilio Willems, Followers of the New Faith: Culture Change and the Rise of Protestantism in Brazil and Chile (Nashville, Tenn.: Vanderbilt University Press, 1967).

[19] Christian Lalive d’Epinay, El refugio de las masas: Estudio sociologico del protestantismo chileno (Santiago de Chile: Editorial del Pacifico, 1968).

[20] Henri Paul Pierre Gooren, Rich among the Poor: Church, Firm, and Household among Small-Scale Entrepreneurs in Guatemala City (Amsterdam, The Nether lands: Thela Thesis, 1999), 153-59.

[21] David Lehmann, Struggle for the Spirit: Religious Transformation and Popular Culture in Brazil and Latin America (Cambridge, Mass: Polity Press, 1996); Cecilia Loreto Mariz, Coping with Poverty: Pentecostals and Christian Base [sic] Communities in Brazil (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994).

[22] Edward L. Cleary, “Introduction,” in Power, Politics, and Pentecostals in Latin America, edited by Edward L. Cleary and Hannah Stewart-Gambino (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1997): 4-5.

[23] Phillip Berryman, Religion in the Megacity: Catholic and Protestant Por traits from Latin America (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1996), 2-3.

[24] Sidney M. Greenfield and Andre Droogers, eds., Reinventing Religions: Syncretism and Transformation in Africa and the Americas (Lanham, Md.: Pwoman and Littlefield, 2001).

[25] Patrick Johnstone and Jason Mandryk, Operation World: When We Pray God Works Handbook, 21st Century ed. (Exeter, Eng.: Paternoster Publishing, 2001). See http://www.gmi.org.

[26] Mark L Grover, “The Mormon Priesthood Revelation and the Sao Paulo Brazil Temple,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 23 (Spring 1990): 39-53.

[27] Mark L. Grover, “Mormonism in Brazil: Religion and Dependency in Latin America” (Ph.D diss., Indiana University, 1985), 75.

[28] James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 2d. ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 563-91.

[29] Grover, “Mormonism in Brazil,” 75.

[30] Mexico was an exception to this practice, because American missionaries were forced out of the country several times between 1913 and 1934, and local members had to be given administrative responsibility.

[31] Tullis, Mormons in Mexico, 207-11.

[32] Donald Q. Cannon and Richard O. Cowan, Unto Every Nation: Gospel Light Reaches Every Land (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 284-301.

[33] Nestor Curbelo, Historia de los Santos de los Ultimos Dias en Uruguay: Relatos de pioneros (Montevideo, Uruguay: Imprimex, 2002), 184.

[34] David Stoll, Is Latin America Turning Protestant? The Politics of Evangelical Growth (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 105.

[35] Retention is a serious problem for the Church. The most comprehensive study of the challenge is David Stewart, “LDS Church Growth Today,” retrieved January 2005 from http://www.cumorah.com/report.html. See David Clark Knowlton, “How Many Members Are There Really?” in this issue, which compares national census data (including self-reports of religious affiliation in Chile and Mexico) with official Church records.

[36] Stewart, “LDS Church Growth Today.”

[37] Cleary, “Introduction,” 9-10.

[38] Stewart, “LDS Church Growth Today.”

[39] Irma Conde, Oral History, interviewed by Nestor Curbelo, July 4, 2002, Rocha, Uruguay; photocopy of typescript in my possession, translation

[40] Rosalina Goitano Ramirez, Oral History, Interviewed by Mark L Grover, July 20, 2002, Buenos Aires, Uruguay.

[41] Quoted in “Pres. Hinckley Urges More Missionary Effort in Venezuela,” Church News, August 14, 1999, 3.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue