Articles/Essays – Volume 16, No. 1

The Millennial Hymns of Parley P. Pratt

Born in 1807 in Burlington, New York, Parley P. Pratt was baptized by Oliver Cowdery in Seneca Lake on 1 September 1830, less than five months after the Church’s founding. Among the first to be called to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in 1835, Pratt published A Voice of Warning in 1837, became founding editor of the Millennial Star in 1840, and, with William W. Phelps and Eliza R. Snow, was one of the most important verse writers in early Mormondom.

In fact, writing verses for Latter-day Saint hymns became almost an obsession with Pratt. He wrote lines to commemorate almost every important occasion in his own life and in the life of the Church. But his favorite themes were the restoration of the gospel and the millennial significance of the restoration. A grandson, Samuel Russell, collected most of Pratt’s verses on these themes long after his death, set fifty of them to traditional hymn tunes, and published them with Cambridge University Press in 1913. The jubilaic significance of the number would not have been lost upon Pratt. The hymns Russell selected were written primarily in two groups: a first set of eleven in 1835 and a second set of twenty-nine in 1840. Five were written between these two sets and five after. What was their message and meaning to Pratt, the Church of his time, and the Church today?

Emma Smith included three hymns from the 1835 set in her first book, Latter-day Saint Hymns, published that same year. This was the year Pratt was called to be an apostle, occasioning a hymn (no. 21) which begins:

Ye chosen Twelve to you are given

The keys of this last ministry,

To every nation under heaven,

From land to land, from sea to sea.

In its last verse this hymn refers to the Lord’s return. There are other millennial themes in this first set of Pratt hymns, but they are dominated by pre millennial or restorationist images. For example, his number ten:

When earth in bondage long had lain,

And darkness o’er the nations reigned,

And all man’s precepts proved in vain,

A perfect system to obtain,

A voice commissioned from on high.

Hark, hark! it is the angel’s cry,

Descending from the throne of light

His garments shining clean and white.

Moreover they are, in my judgment, muted in fervor, often using the quiet beauties of nature as a leading metaphor. The first of the set begins:

Hark! listen to the gentle breeze

O’er hill, o’er valley, plain or grove!

It whispers in the ears of man

The voice of freedom, peace and love.

The song goes on to speak of flowers, birds, streams, and mountains in a manner that remind one of Phelps’s “Earth, with Her Ten Thousand Flowers” written near the same time.

The latter 1830s, such turbulent and difficult times for the Mormons, are powerfully documented with five hymns much darker in tone. Some were not without their humor, at least in retrospect, such as “Adieu to the City” (no. 46), which Pratt wrote upon leaving New York in 1838 after a difficult and often disappointing ministry:

Adieu to the City where long I have wandered

To tell them of judgments and warn them to flee;

How often in sorrow their woes I have pondered!

Perhaps in affliction they’ll think upon me.

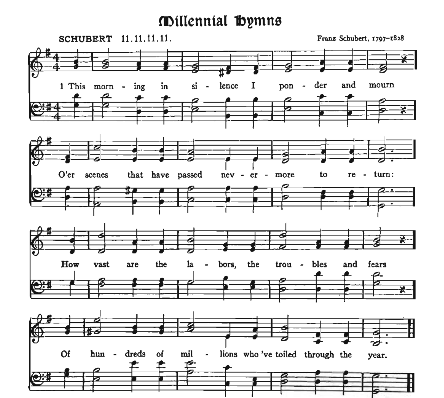

More typical, however, is a hymn written in 1839 (no. 49).

This morning in silence I ponder and mourn

O’er scenes that have passed nevermore to return:

How vast are the labors, the troubles and fears

Of hundreds of millions who’ve toiled through the year.How many ten thousands were slain by their foes,

While widows and orphans have mourned o’er their woes;

While pestilence famine and earthquakes appear,

And signs in the heavens throughout the past year!How many were murdered and plundered and robbed

How many forsaken and driven and mobbed!

How oft have the heavens bedewed with a tear

The earth, o’er the scenes they beheld the past year!

The list of woes is relieved only by the millennial promise of the last three stanzas. The millennial themes appear more strongly during this interregnum of 1836 to 1839 — nearly always at the end of several gloomy stanzas — as the promise of hope to the beleaguered Saints. This seems a defensive time in which the millennial embers are fanned up in reaction to the otherwise chilly fortunes of Pratt and the Saints.

Then came the mission of the Twelve to England and a great outpouring of twenty-nine hymns in one year. (Pratt’s remarkable productivity is in part an eloquent indication of what deadlines will do for output, as he published a new hymn book in that year and began editing the Millennial Star in which many of his hymns were printed. He needed the material for both projects.)

The 1840 set begins with a hymn written especially for the first number of the Star, a hymn of power and confidence—Zion on the offensive!

The morning breaks; the shadows flee;

Lo! Zion’s standard is unfurled.

The dawning of a brighter day

Majestic rises on the world.The clouds of error disappear

Before the rays of truth divine;

The glory, bursting from afar,

Wide o’er the nations soon will shine.

This bold, millennial declaration is repeated in numerous contexts through dozens of metaphors from that time until his death in 1857. There are less defiant hymns in this set; for example “As the Dew from Heav’n Distilling (no. 41), but “The Morning Breaks” is surely the archetype of the group. During these years one can also see a focusing on Christ — his triumphant return and central place in the millennial world — as in hymn numbers twelve and fifteen.

Behold the Mount of Olives rend!

And on its top Messiah stand,

His chosen Israel to defend,

And save them with a mighty hand.Hosanna to the great Messiah,

Long expected Savior King!

He’ll come and cleanse the earth by fire,

And gather scattered Israel in.

It may be that his apostolic responsibility to testify of Christ weighed more heavily upon him as he preached the gospel in England.

Pratt always describes the millennial life with one or more of the following words: light, peace, comfort, unity, and above all, joy. Surely his certain assurance that these conditions were real and lasting in human experience and would one day prevail gave him and the early Saints courage to face difficult times. Even the two hymns Pratt wrote in 1837 for his own solace when his first wife, Thankful Halsey, died ended with stanzas holding up the millennial promise.

Yet it seems a bit odd to me, growing up under the bleak shadow of the mushroom cloud, that Pratt’s world was to him so gloomy a place that his primary source of comfort was that hope. He lived, after all, in the ebullient age of Jackson, in an America burgeoning with optimism and faith in progress, comforted by the vista of limitless lands and opportunities on the western horizon. We are the ones who need the hope of the millennial promise. For in my judgment the conditions Pratt deplored have been squared or even cubed since his time, as love has waxed colder still and we all, ever more like sheep, have gone increasingly astray.

But, more than most realize, Latter-day Saints still live with that promise. The embers still glow and need but a little breath to make them burst into bright flame. The symbol of the RLDS Church, for example, is a millennial image of a child leading a lion. Their pastors and members have frequent discussions of what constitutes, as they put it, a Zionic community. They continue to pursue plans to build a temple in Jackson County, Missouri.

Several hundred Samoans of Utah Mormon persuasion began in 1969 to migrate to Independence, Missouri, acting, they felt, under inspiration as part of the preparation for Christ’s return. It is remarkable how quickly Utah Mor mons take up food storage at the hint of a rumor. In a memorable general conference address, Apostle Bruce R. McConkie wept openly as he assured Mormons that “soon the great millennial day will be upon us. This is thy day, O Zion! ‘Arise, shine; for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee. . . .’ “[1]In October 1976 President Spencer W. Kimball explained almost casually that the first Quorum of the Seventy was being reorganized, “anticipating the day when the Lord will return to take direct charge of His church and kingdom.”[2]

One of the most powerful Pratt hymns ends its first stanza with words which ring true to all who see evidence of strong tides of millennial expectation among contemporary Mormons:

Gently whisper, All is well!

Now’s the day of Israel!

[1] Bruce R. McConkie, address, in One Hundred Forty-eighth Annual General Confer- ence of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, held in the Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, Utah, April 1 and 2, 1978 (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1978), p. 82, hereafter cited as Conference Report.

[2] Spencer W. Kimball, in Conference Report, Oct. 1976, p. 10.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue