Articles/Essays – Volume 41, No. 2

The Newlyweds

After our two-day honeymoon in West Yellowstone, we move into this one-bedroom place above the Modern Plumbing & Heating building in Rigby. There’s a door right on Main Street that opens up to a barn-red flight of stairs. Only two places up there—ours is on the right, 1A. The windows are tiny, shiny squares that glare across the street to Dolly’s Ragtime Bar and the parking lot of Ben Franklin’s Crafts. Other than that, there’s not much else to look at.

The hallway’s narrow, so it’s tricky moving stuff upstairs. Luckily, my grandma gave us this table with foldable legs. I sat at it every Thanksgiving growing up—the kiddie table—and since I was the last grandkid to get married she said I could have it. One of the legs is bent due to a post-turkey scuffle with an older cousin. He won, but I got the table, right? Kendra fixed it by stuffing a folded-up paper plate underneath. It still wobbles if you nudge it the right way.

My dad got me hired as an apprentice plumber at Modern. He said Randy owed him. Kendra got a part-time job at Triple J’s Foodtown a few blocks away. She bags groceries and answers phones three nights a week.

So, everything is going okay, I guess, other than we’ve been watching for our neighbor. We keep getting her mail. Jenn Bliss, Apartment 1B. No one answers when we knock. The old door is warped, and there’s no room to slide it underneath. But we know someone lives there because sometimes we hear people laughing and moving up and down the stairs late at night.

We don’t see her until Saturday. When we walk in from Main with our groceries, she’s locking her door. She starts down the stairs. We walk up.

“Hi there,” Kendra says, stopping to talk.

Jenn pushes right between us. “Sorry, hons. Late for work. Come by tomorrow. We’ll chat.” She leaves without saying more, heels clacking the whole way down.

When we get inside, Kendra says, “What was that?”

I pile the plastic bags on the table, which wobbles. “Jenn, I guess. She looked nice.”

“What kind of nice?” she says.

“Good nice.” I open the fridge, put away the eggs.

“How old do you think she is?”

“Maybe thirty.”

Kendra puts things away under the sink and then goes to the living room, which is actually the same room as the kitchen, just where the linoleum stops and the carpet begins. “What do you think she does?” she asks.

“Who knows?” I follow her. “What do you think?”

Kendra sits down at the table and picks up three letters marked as Jenn’s. She puts her feet up on one of the folding chairs and taps the mail on the table. “She looks kind of sleazy.”

I take the letters and shuffle through them. Mountain Power. A card from the dentist. Cable bill.

“Maybe she’s a dancer,” she says and looks up, grinning.

“Maybe she’s a dancer,” I repeat, and sigh. Sometimes Kendra is so immature.

On Sunday afternoon—when we’re supposed to be in church, Kendra’s mother, Tammy, insists—we make a plate of cookies for Jenn. Really, we just take them out of the wrapping and arrange them on an old St. Paddy’s Day plate. A shirtless, hairy man answers when we knock. The door stays open a crack when he goes to get her. Faint giggling floats out of the apartment. Jenn comes to the door, no makeup, hair in a ponytail, a pink tank top.

“Hey, you two,” she says, in this nasally, fake whine. It looks like she’s wearing a piece of bailing twine for a necklace.

“Hey,” we say at the same time. Then there’s that new-neighbor awkwardness we’ve never felt before.

Kendra says, “Just wanted to introduce ourselves. I’m Kendra Smithfield. This is my husband, Chad.”

I nod. Jenn looks at me and we lock eyes—hers are greener than garden peas.

“You two are married?” she says. “You’re just kids! How old are you?” She’s obnoxiously chewing gum.

“Eighteen,” I say.

“Seventeen,” Kendra says.

She opens the door a little farther and glances back at the man. He watches television and doesn’t respond, his stomach rolls lapping toward the elastic band of his navy blue sweatpants.

“So, did you have to?” Jenn says in a low voice. She smirks, pumps her eyebrows.

“Have to what?” I blurt.

“Get married,” Jenn says. “You know, the doc tell ya you’re in love . . .”

“Well,” I start.

Kendra shoots me this look, butts in. “No. We were high school sweethearts.” She says it like it’s some trophy to line the walls of Rigby High.

Jeez, I think, staring at Jenn. Kendra’s eyes are this sidewalk gray, not green one fleck. And that stray piece of twine, floating down and toward the creamy crease climbing out of her shirt…

“How long?” Jenn asks.

“A week and a half,” Kendra answers shortly. She caught me looking, I know it. I glance upward to the wall jambs and count the flakes of peeling ceiling plaster.

Jenn swears in this long, drawn-out way. “Gawd.” Sounds from the TV waft to us. “Ya’ll lived in Idaho forever?” she asks.

“Yeah—Roberts, Hamer,” I say putting all my weight on one foot, then the other, making the wooden floor creak.

“We made these for you,” Kendra says. She holds out the cookies and nudges me.

I offer the letters. “We keep getting your mail. Sorry.”

Jenn takes the plate and letters. She smiles. “Ain’t you two sweet.” She holds up the mail and kind of waves it back and forth in the air.

“Let us know if we can do anything,” I say, feeling my cheeks rush and redden.

“Actually, I’m leaving town for a week. Pick up my mail?” she says.

“Sure,” Kendra and I say at the same time.

“You might just get it anyway,” Jenn says.

Kendra chuckles politely.

When we’re back inside number 1A, Kendra says, “Weird.”

“Yeah, she was,” I say.

“No, weird because you checked her out.”

I try to counter but can’t. Instead, I turn on the TV and search for a baseball game. Big fan—I used to play, before getting hitched. Kendra pur posefully avoids me and spends the afternoon on a Tammy call. When she’s done, she comes out for a glass of water. Her eyes are puffy and red. I ask her what’s wrong and tell her to come and talk, patting the seat cushion beside me, but she opts to drink alone in the bedroom. I’m frustrated—how long can a man live like this?

On Tuesday, while Kendra works late shift, I get the mail. There’s another letter for Jenn. I set it in the stack. For dinner I eat a can of chili and a soda, both cold. Cheetos for desert.

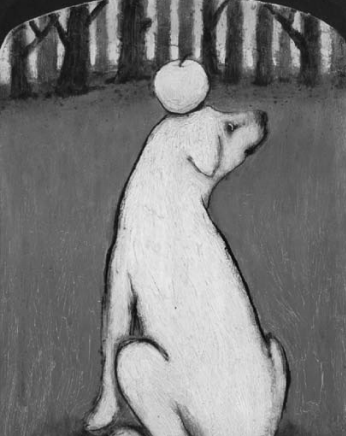

There’s nothing on, so I sit down and thumb through the mail, putting it in two piles. One for Jenn, one for us. Ours has a flyer for the canned food sale at Triple J’s and a handwritten note from the postman to fix the mail slot. Jenn’s has another cable bill, an envelope with no return address, and a postcard featuring a dancing bear. The printed caption on it reads “Circus Capital of America, Peru, Indiana.”

I organize the piles, then reorganize them. Biggest pieces on the bottom, then longest, then fattest. Gotta make sure all face the same way—Kendra says I’m a bit over the top, a bit eccentric. When I pick them up and tap them on the table to even the edges, Jenn’s postcard slips out and falls like a pinwheel onto the beige carpet. It lands picture-side down. Handwriting stares up at me.

I don’t read it, though. I snatch it from the floor and put it back on top. Then I go straight to the bedroom, flop down on the bed, and watch the ceiling fan. Almost two full minutes go by before I return and read the postcard. It says:

Jenn,

Thanks for the weekend. Don’t be a stranger.

Paul

The writing is heavy. The top of the “T” shoots at a high angle across the card, and “Paul” is underlined three times. I put the postcard at the bottom of the pile, cover it with the other letters, and walk downstairs to fix the mail slot.

The flap isn’t broken, just stuck, so I go back upstairs for a screwdriver. My eyes are drawn to the mail again. I take the postcard and spin it by its corners, hypnotizing me into circus daydreams. The weight of the screwdriver in my back pocket reminds me of the task at hand. I head for the door.

When I open it, Kendra’s there. It startles me—I didn’t hear her come up.

“What are you smiling about?” she teases. She seems happier today.

“Me?” I say.

“No, Harry,” she says. That’s what we nicknamed Jenn’s friend. What an ape.

“Just thinking about something.”

In the hallway, with the door open, I grab her tightly around the waist. She squeaks. Her eyes look like river rock.

“What are you doing?” she says, pulling away a little.

“I don’t know,” I say. “Just playing.” I let her go.

“Where are you going?”

“The mailbox.” I flash the screwdriver, return it to my pocket.

“Where’s the mail?” She says this more seductively, almost meowing.

I point to it on the table and back out the door. As Kendra shuts it, I say, “Don’t be a stranger.”

“Huh?” The door freezes.

“Nothing,” I say. “Forget it.” I take the stairs two at a time, palms barely grazing the handrails.

I sleep restlessly and lie awake from five on. When Kendra finally wakes up, I coax her into a quick session. At first she’s a little hesitant. We’re on a schedule. We’ve done it nights for the past year, mostly in clammy backseats and dimmed basements. It got best—I say best, it always was a little guilt-filled—right before the drugstore stick turned purple. It got worse when she lost it in Yellowstone.

I mention that the neighbors can’t hear. Then she’s all right and relaxes.

I’m late for work. Randy reams me. When I lie and say I slept late, he calls me on it. The ceiling is paper thin, he says and doesn’t crack a smile.

Thursday, I have Kendra call in sick for me. She’s cool with it but tries to get me to go out to Hamer. When she asks, I cough violently and pull the covers up to my chin, lying still until she leaves.

I murder the morning around the apartment. Baseball Today, the slop operas—nothing does it for me. All I can think about are dancing bears, acrobats, sharing Cracker Jacks with Jenn. Except, in my mind, everything is bathed in a brilliant sheen of green, the same shade as birthday balloons, avocado skins, kiwi fruit. It’s a circus, all right, but the big top looks like a turtle shell, the clowns have pale, grassy faces and cucumbers for noses. The color attaches to everything. I thumb through the mail and reread the postcard. “Paul,” I say out loud, in the empty apartment. “Paul.”

Kendra told me that the mail comes around two. I check it at 1:50. Then at 2:10. When it finally comes at 2:31, I’m sitting at the top of the stairs, fists propped under my chin, pigeon-toed, impatient.

After I’m sure the mailman’s long gone, I gather up the correspondence and fly upstairs. I sort. More bills, more letters. No postcards. Nothing comes for us. Jenn’s pile doubles.

I notice the cable bill’s flap has worked slightly open, exposing a corner of the bill. Suddenly, I crave macaroni.

As the water boils, I whistle and glance across the living room toward the apartment door. I would hear Kendra coming, for sure. Plenty of time. Just in case, I open up and look down the flight of stairs.

The steam burns my hand until I put on a tattered oven mitt. The letter pops completely open after a few seconds in the steam. When the bill slides out, I sit back down at the table and read through its contents. My palms sweat from the steam, or something else, I don’t know. I’m not hungry any more. I mean, it’s just the cable bill, but it’s something more. When I’m done, I examine the other letters for loose flaps and hidden openings.

I have it back in the envelope and glued shut when Kendra gets home. Before she can ask if I’m feeling better, I’m at her, pushing into the back of her hair, panting.

“Did we get anything in the mail?” she asks, pulling away from me. I let her go after guiding her past the table and to the fridge. While she eats, we make small talk.

“Today go okay?” she asks. She seems distant again.

“I missed you. Other than that, fine.”

“What’s gotten into you?” she says flatly and spoons through her stew.

“Nothing,” I say.

“You’re just so, I don’t know . . . giddy.”

“Really?”

“Yeah, usually you’re just kind of quiet.”

Her eyes look like pencil lead, bike tire rubber.

“You need to tell me something?” she says. “How come the change?”

“What change?” I say.

“You tell me,” she says, and waits until I look at her.

I can’t answer for a while. Finally, I say, “Randy says I might get a raise soon. He came up and told me.”

“Really?”

“Yeah,” I say.

She’s pretty happy about that and comes around to sit on my lap. We kiss for a while before we go into the bedroom. For the first time in a while, it’s easy.

Friday. Restless. At work I check my watch every ten minutes. Once it passes two, I’m even more antsy. Time grinds by slower than Christmas Eve.

But there’s nothing inside the door when I get home. I trudge up the stairs and take my clay-covered boots off in the hallway. Before knocking, I slide over to Jenn’s apartment and quietly try the knob. It’s locked. Our place is locked too, and Kendra doesn’t answer. It takes a minute to dig my keys out from the bottom of my lunch pail.

Kendra is sitting at the table, the two piles of mail in front of her. Two angry pig-tails jut out near her neck, she’s not wearing makeup, and her jaw is squarely set. I tell her thanks for opening the door, that that was really nice. She doesn’t say anything back. It gets worse.

When I come out from the kitchen, she holds up Jenn’s cable bill. The flap is open—my glue job didn’t hold. She shakes the envelope and the papers fall out.

“What’s this?” she says.

“Looks like Jenn’s mail.”

“Why is it open?”

I shrug, crack a soda.

She repeats her question, and then zeroes in with a drawn-out, “Chad.”

“I’m not sure. Did you open it?” I head for the TV.

She starts yelling at me. That lasts for a while. She cries some too, sniffling about privacy.

It takes a while, but I bust. “Fine!” I say. “I did it. Happy?”

“Are you?” she asks.

“I’m fine with it.”

“Oh really?” she says. She throws it down on the table. “You’re happy, opening up someone else’s business. What if everyone knew about us? How would that feel?”

“Why would I care?” I shout without thinking.

Kendra crosses her arms and sticks out her bottom lip.

“You started it,” I say, “Asking about her, wondering what she did. It wasn’t my fault the envelope ripped.”

She doesn’t really answer, just grinds her heel into the carpet.

“Yeah, it was open. The papers fell out on the stairs.”

She walks around the living room, gathers up the two piles of mail and goes to the bathroom. The door slams hard, and she locks herself inside. I stand there for a while, go over and try the knob, but she yells for me to leave her alone. I pound one sharp, staccato burst on the door with my fist, but leave it after that. It’s the second time I’ve stared blankly at a locked bathroom door during our marriage. Our bed, a hand-me-down from my aunt’s basement, doesn’t give when I lie down. It makes for another restless night.

I’ve made her fume before. There was this girl no one at school knew about, some quiet blonde in government. Turns out she lived across from me through the neighbor’s hay field, and we started meeting up by the headgates. When Kendra found out, she got drunk for the first time and made out with Jarrett Buckett dirty style. It took us a while to work things out after that.

So I know it’s best to leave her alone. I don’t see her again until I start frying eggs and bacon for breakfast. She pulls on the back of my T-shirt and wraps her arms around my waist.

“Hey, you,” she says. She’s wearing her navy blue robe. It’s covered with white outlines of teddy bears. Her eyes rove around but never meet mine.

“Hey.” The grease pops. “You better stand back. It’ll burn.”

“I’m okay,” she says. She squeezes me tighter. It’s always this way, even after Yellowstone. Just give her a minute, let her breathe. She’s a real trooper.

While we’re eating, I say, “Look. About last night . . .”

“It’s okay,” she says. “I got a little mad, that’s all.”

“No big deal, right?” I say.

She smiles and shakes her head no. “Don’t be mad,” she says. We eat quickly and make love on the couch. She seems A-OK.

After, I go to the bathroom. Surprise—I’m blown away. The letters are scattered everywhere: along the sink’s edge, the back of the toilet, in the bottom of the dry tub. I stand in the doorway, confused. Kendra wraps me from behind again.

“Who do you think Paul is?” she says. I’m stunned.

“You know, Paul from the postcard. You don’t have to hide it.” She walks in and fishes it out of a pile, points to a cheesy thumbprint covering one corner.

I shrug.

“Maybe he’s her manager,” she says, and starts to tickle me.

I realize something big, and grab the letter with the blocky handwriting, the one with no return address. Side by side, they match nicely.

“What did you think about the cable bill?” I say. It’s out of the envelope, under a hairbrush.

“Naughty, naughty,” she says.

I hold up the letter and the postcard. “Do you think?”

I see her make the connection. “Maybe.” She starts to gather up the mail.

In the living room, I clean the dishes off the table and backhand the crumbs onto the floor. “When’s she coming back?” I ask.

“Tomorrow sometime,” she says, carrying all the mail in the crook of her arms, like she would a baby. She spreads it out across the table.

I find my stainless steel trout knife under the bed. Without its sheath, the blade gleams clean, well-honed.

Kendra is organizing the mail on the table, sorting bills from letters, letters from cards. She sees the knife and scoots two chairs side by side. We cross our legs underneath us and lean over the table.

“Softly,” she says. “Carefully.”

I bite the tip of my tongue. She grits her teeth.

I slide the blade under one of the letter’s flaps, sawing slowly through the glue. We open three letters and read their contents out loud. Halfway through the fourth, the downstairs door slams shut. Light, noisy footsteps ascend the stairwell.

I stare at Kendra. Her eyes get bigger than I’ve ever seen them—big gray orbs of panic. My knife stabs clear through the envelope, skewering it.

“It’s Saturday, right?” I whisper.

The clacking stops at the top. Kendra can’t answer. We slump down in the chairs and hold our breath. Jenn knocks on our door. “Hello?” she says. “Hons?” She pounds a little harder.

I set the knife and letter on the table. Both of us sit still as china dolls. Kendra takes my hand and we bow our heads, like children, praying for the knocking to stop.

The knocking reminds me of the steady thump thump thump of my mother’s borrowed Buick Regal as we pulled onto the shoulder on our way to Yellowstone two weeks before. There, Kendra’s contractions set in. The pee test proved what we knew deep down, so we went to the courthouse and sealed the deal, but kept living with our parents for a while. Finally, though, we decided to tell them, and we let the cat out of the sack separately, but on the same day. They interrogated us about something in the oven, but we denied it, argued that we were “just in love.” No big deal. “I mean, you guys got married right out of high school,” I remember pointing out to my folks. “What’s a year early, anyway?”

So the Smithfields called the Bisbees and pooled some money for a honeymoon shack in West Yellowstone. “What’s a wedding without a honeymoon?” my dad had said after I told him. He said it with a grimace. I could tell he was heartbroken.

We left, and then Kendra started cramping. She told me to keep driving, so I slammed the Buick up to eighty and made it to Yellowstone in under an hour. As soon as we got to the room, she stripped and showered. I’m not sure what happened. She locked the door. She sobbed and sobbed. Then I took her to this little hippie hospital, and they made sure it was all cleaned out. The rest of the weekend we stayed inside watching fuzzy television, wrapped around each other, and swearing that no one ever needed to know.

Kendra says I’ve lied enough, so I have to take the mail to Jenn. I say I wouldn’t have even cared if she hadn’t brought up the dancing stuff. She says she’s sick of me causing problems. I say she doesn’t know what she’s talking about.

We glue the flaps back down and lie low in the apartment for a day. Sometimes we hear Jenn leave. Sometimes we don’t.

The skewered letter can’t be glued, so I cover it as good as I can with transparent tape, hoping it looks like the post office’s mistake. On Sunday night, I walk it over to apartment 1B, knock, and hand Jenn the pile of mail without a word. She asks some questions while sifting through the bills. In that brief moment that her mouth moves, nothing registers for me. I notice her dingy tan teeth; her pale, thin lips; the wrinkles forming around her bare shoulders. When she stops and looks up, expecting an answer, I’m long gone.

The next day, Tammy shows up with her bishop. They sit us both down at the table. Tammy starts in with this stern lecture about growing up. Bishop Clark follows up with the sanctity of marriage. Tammy butts back in about the loss of a loved one. When I look at Kendra, realizing she’s told, she starts crying. Her eyes are duller than ever.

I don’t know where Kendra’s mom gets off, bringing in the cavalry, ordering me around. When someone starts knocking, I’m anxious to answer, and shoot out of my chair to get it.

I recognize the face—Harry. He’s wearing a blue mechanic’s jacket with PAUL stenciled above the right pocket. His mouth is one little line, puckered a bit, and before I can say anything he pops me hard with a stiff straight right. From the floor, before my eye swells shut, I see the damaged mail clutched in his left hand. He towers over me and grunts about invasion of privacy. My head aches with a resonant fire alarm echo.

The bishop lumbers over and shoos him into the hallway, shutting the door. Kendra scoots my head onto her lap and runs her cool fingers over and over through my hair. She coos and calls me sweet names. Cold sweat forms all across my forehead.

From the kitchen, Tammy brings a bag of frozen broccoli wrapped in a paper towel and plants it on my brow. The two women are speaking in low tones when I black out.

Randy fires me for lying, and we get booted from Apartment 1A. He never did like me. It’s okay because we get our deposit back and use the money for a down payment on a 1988 Chevy Corsica that belonged to Kendra’s older sister. Kendra gets me a job stocking at Triple J’s. We carpool three times a week from my parents’ place, where we stay. The kid die table is stashed in the Bully Barn out back.

The swelling and discoloration around my eye are gone in a few weeks. Sometimes, though, when I’m in the canned vegetables aisle making sure the Garden Peas aren’t wall-faced, I think about Jenn and my vision of that strange circus, and this flush of curiosity surges through me. It burns around my eye. The bishop tells me that all of us face temptation, but it’s really a matter of action. He says we have to choose. So, sometimes I stay away from aisle 9—but sometimes I can’t help but request it and spend all night there.

I climb the ranks faster than usual—the up-and-ups like my organizational skills—and earn a spot as receiving manager within a few months. It’s graveyard shift, not bad. Jenn pops in and out of my memory the entire time. I can’t wait to see Paul again; I can swing like a champ. I practice with the broom handle in the break room.

Late one night, an eighteen-wheeler brings in a massive shipment. The grizzled old trucker nods and jaws about fuel prices, then mumbles about sleeping in the cab. He leaves after opening the trailer. Before Jessie or any of the other stockers come out, I truck down a crate, open it, and extract a can. In the reddish glare of the taillights, even in the haze, I know it’s the label for Western Family Emerald Peas. Aisle 9, on the right. I toss it up in the air a few times, judging its weight, and try to picture a perfectly green version of Kendra.

It doesn’t click. I don’t know if it’s the dark asphalt blanketed by the night, or the cave-like appearance of the closed loading dock door that sets me off, but all I can imagine are Kendra’s shadowy, tear-glistening eyes when she opened the bathroom door in Yellowstone. I cock my arm way back and chuck the can into the desolate parking lot. It soars lopsided, whooshing end over end until it lands with a hollow thunk. Under an empty, starless sky, I listen to the can roll off the curb and disappear. The halogen floodlights flip on; I’m bathed in synthetic yellow light. The others come out with dollies and begin unloading.

I leave before the sun rises, park the Corsica in the barrow pit, and let myself in the back door. In my old bedroom, curled in my old bed, Kendra is asleep. The sounds of her breathing fill the room. It’s timid and soft, comforting beyond belief. I don’t undress, just climb in with her, and run my fingers through her long hair until she finally blinks awake.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue