Articles/Essays – Volume 14, No. 2

The Odyssey of Sonia Johnson

1936. Sonia Harris is born on the Waushakie Indian Reservation near Malad, Idaho.

1948. She moves with her family to Logan, Utah, where she graduates from high school, works in a bank for one year and then graduates from Utah State University with a B.A. in English.

The third child in a family she describes as “five only children” because they were so far apart in years, Sonia traveled from one small town to another in the wake of her father’s seminary teaching career. When she was twelve years old, the family finally settled down in Logan.

She describes her parents as scripture-loving people. “My father used to follow me around quoting from church books.” Her mother, who never worked outside the home, held a variety of time-consuming church positions; she was “all the presidents a woman can be in the Church.” Sonia claims she inherited a talent for oratory from her father and habits of prayer and fasting from her mother. She remembers too that she and her mother did all the washing and ironing on Saturdays while the men were “out doing what they wanted to do. I had to pick up their dirty clothes.” She was bitter about that as well as rebellious on other counts. “I must have started out rebellious because my parents went through life being embarrassed.” Her parents dreaded going to testimony meetings with her because they were never sure that the ward would be safe from their daughter’s chastisements. Two incidents were especially memorable: one when she stood up in testimony meeting to argue publicly with an MIA lesson and the other when she was seen after church talking to a polygamist. “Why, you would have thought I’d dropped a bomb on those people.”

Her short stint working in a bank convinced her to return to school. She describes the experience as one that made her feel that she was starving. When she told Alma Sonne, one of the bank directors, that she was leaving to return to school, he scolded her. Women didn’t need an education, he said. They needed only to be wives and mothers, and a bank was as good a place as any to wait for Prince Charming.

She worked her way through college with a variety of secretarial jobs at the university. In one of her courses, she met Richard Johnson of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, who was shortly to join the Church. In this same course they learned how to administer interest and I.Q. tests, tests which proved to them that they were a perfect match.

1959. Sonia marries Richard Johnson and quits school while he works on his master’s thesis in mathematics and psychology.

She quit because she thought it was expected of her even though Richard kept saying, “This isn’t right. I don’t like it.” She describes the first two years of their marriage as “miserable” mainly because she was not working on her own degree.

1960. Sonia and Richard move to American Samoa where they teach math and English at Pesanga Church School, later the Church College of Western Samoa.

For several months the Johnsons lived in an American compound where their only interaction with Samoans was through allowing them to splash under an outdoor water pump to which they had installed a shower head. One of the young men who delighted in this form of recreation became a good friend of Sonia’s seventeen-year-old brother Mark who had come to live with them. When Mark returned to the states, he took his new friend with him to become an ad hoc member of the Harris family.

1970. Sonia and Rick move to the University of Minnesota so that Rick can obtain his Ph.D. in Educational Psychology. Their first son, Eric, is born there.

Hazel and Ron Rigby, friends of the Johnsons during their school years, describe them as thrifty to a fault, living as they did in a trailer and driving a motor scooter. The Rigbys remember that Sonia bundled the baby in news papers and braided rugs for their chilly rides to church. They seldom ate out, and when they did, they were likely to look at the prices on the menus and leave. They were “addicted” to badminton and word games, and Sonia acted in ward and university plays. According to Hazel, “Sonia accepted the gospel of women’s work,” and although she was taking classes herself, she never asked Rick to help her with the housework or child care.

1963. Rick accepts an appointment at Rutgers. He urges Sonia to finish her degree also. Their second child, Kari, is born.

Rick arranged to limit his teaching hours so he could be with the children while Sonia finished her degrees. When the Rutgers English Department refused to allow her “hours and hours and hours” of credits from other universities, she changed her major from English to Education. “You’re just as smart as I am,” Rick kept saying. “You’re just as talented.” She wrote a master’s thesis the first year, a doctoral dissertation the next.

1965. Richard accepts an American Institute for Education research grant in Lagos, Nigeria. Sonia teaches English at the American International School there.

Thrift was one thing, poverty another. In Africa Sonia saw the grueling suffering that she was to remember for the rest of her life. She describes her home on a hill overlooking a lovely little valley. “Everybody in that valley was slowly starving to death. If anybody lived to be thirty-five, that was considered old.”

1967. The Johnsons return to the United States where Rick teaches statistics at Stanford and their third child, Marc, is born.

Returning to the U.S. was culture shock in reverse. “When I saw all those fat people in all those fast food places eating, eating, I came home and vomited.”

But Palo Alto was a good place to be. “There were interesting people there then. I was not one of them.” She especially remembers discussing the Negro problem with a young man who said in a meditative voice, “In ten years the problem of women in the Church is going to make the black question look like child’s play.”

1969. Rick’s wanderlust takes them overseas again, this time to Malawi in Central Africa (home of “Dr. Livingston, I presume”).

Sonia worked full time at the University of Malawi teaching English, education and drama. She was impressed with the work of the Seventh-Day Adventists in that country, especially their medical contributions: “They must have pleased God a lot.”

1971. Their assignment finished in Africa, they return to Stanford and Palo Alto for the second of their three stays there.

It was in the Palo Alto Ward that Sonia heard of the directive forbidding women to pray in sacrament meetings and felt the first real stirrings of political activism. “I suddenly realized that the fear of women was strong in the Church.” The bishop was unable to answer her questions about the directive, being puzzled himself.

1972. Rick obtains an appointment in Korea, and Sonia once again finds herself teaching at an American school. She is also called to be Relief Society President in the English-speaking branch there.

During their stay in Korea, the Han River flooded and buried many of the residents of Seoul living near it. Sonia went to the Mission President with the news that she was organizing her branch to deliver blankets and food to the sufferers. His response shocked her: “What we do here is preach the gospel of Christ.” He would help rescue the members, but he would not deliver supplies to the non-members. “I really felt rebellious about that. I guess I was starting to get ‘uppity.'” But Korea also included Sonia’s most exciting teaching experiences: at the University of Maryland’s Far East Division, at Seoul University and at two Buddhist universities.

1974. The Johnsons sell their belongings in Korea and go on vacation to Malaysia, where their youngest child, Noel, is born.

It was a traumatic experience to have a baby in a native hospital in alien surroundings. She lay on a table which was covered with a red rubber sheet in a room where dozens of other women were also giving birth on tables, without attendants. Friends and relatives looked in through the open windows while the cleaning help wandered about. “The native women knew enough to bring cloths to cover themselves. I had naively supposed they would give me a gown to wear, so I was the only bare-bottomed woman in the room.”

1975. The family returns to Palo Alto jobless, but Rick soon accepts a job as part of a traveling team which implemented government education programs in twenty one states. Sonia is the other half of the team.

The Johnsons always managed to find a church to attend on Sundays and came to think of themselves almost as itinerant Sacrament Meeting preachers and passers—Eric, just turned twelve, was often the only deacon in the small wards and branches they visited. Sonia trained the children intensively in English, especially in poetry and essay writing. Rick taught them math, and Sonia read to them every morning from the Book of Mormon and other major books. Eric said recently that he “misses lying around on the floor listening to Mother read.”

1976. The family settles in Sterling, Virginia where Rick accepts employment at the Virginia Polytechnic College and University in Reston and Dulles. The Church announces its opposition to the ERA.

The Johnsons deliberately settled on their quiet, treed lot so that their children could stabilize. One of the first things Sonia did was to call her old friends the Rigbys who had settled in Virginia. She remembers hanging up the phone and saying, “I hope I don’t ever get to be like Hazel.” It was obvious that her fellow-traveler from graduate school, veteran of ward road shows and sleepless nights with small children, had turned into a feminist.

She began to think about what she would do next. “I began to think, ‘It’s my turn now.’ I know that sounds selfish, but Rick had helped me get an education, and I wanted to use it.” She felt guilty about wanting to apply for full-time work, so she called her family in Logan and asked them to fast and pray about her needs.

Meanwhile, the Johnsons’ effect on the Sterling Park Ward was much the same as Sonia’s had been on the old First Ward in Logan. A conservative collection of young, fast-growing families, it probably did not know what to make of the outspoken family. “We started out teaching a family relations Sunday School class, but that was short-lived. Rick couldn’t stand priesthood meeting. He said they did nothing but sit around talking about how happy they were not to be women.” Rick solved the problem by attending church at nearby Hamilton Branch. Sonia accompanied him for a time, teaching Gospel Doctrine there, but she was “too strong for them, too.” Her most rewarding church job—playing the organ—was given her at Sterling Park, so she attended the branch in the morning and the ward in the evening. She was also called to teach Relief Society.

Some of the women liked her lessons well enough that they asked her to teach a poetry-writing class, a class that produced a dramatic poetry presentation in local stake and ward Relief Society conferences. Sonia’s own poetry was part of the production.

1977. International Woman’s Year begins. The IWY Conference in Utah was ridden with controversy (as Dixie Snow Huefner’s article in Dialogue Vol. XI, 1 de scribes). Sonia marches in the ERA Parade in Washington, D.C.

Sonia was ripe for a cause. As Teddie Wood later put it, she was the perfect choice. She was not working except for ad hoc editing jobs; she was not well known; and she was the perfect example of the model Mormon woman, descended from pioneers, zealously active. When her loosely organized group of friends—Hazel Rigby, Maida Withers and Teddie Wood—marched in the ERA Parade in Washington, D.C, Sonia joined them. They and their children carried hand-made signs and wore “Mormons for ERA” buttons. The little band gathered immediate attention from grateful ERA supporters and irate Mormons. “Some students from BYU took us aside and warned us that we were of the devil.

“I never realized before that I needed the women’s movement. I thought it was for women who weren’t happy and didn’t like men. I had always been a happy person except for certain adolescent periods. I had a good husband, good kids and a good church. But when we moved to Virginia, and I began hearing long diatribes from the pulpit about the ERA, I became very dis tressed.

“When the Church began to oppose ERA, that changed my life from night to day. Nothing had ever been like that before. I had a very abrupt awakening. When I look back, I can see that I had been accumulating data all along. My unconscious was getting fatter and fatter and was about to burst.”

1978. The Church restates opposition to the ERA and to the voting extension (May and October). Sonia testifies in favor of the ERA extension before the Senate Subcommittee on the Constitution (August); Regional Representative Lowe and Stake President Cummings organize Oakton Stake Relief Society to lobby against ERA in Virginia (November).

“Her language is pointed, sharp and may be threatening to men,” Maida Withers says of Sonia, “especially to Mormons who don’t know how to relate to women except on certain levels. When you act like a colleague or an associate, men can’t stand it.”

Orrin Hatch was to learn the truth of that statement. Because Maida, Teddie and Hazel were all on vacation when the request came for a Mormon to represent the pro-ERA stand on the extension hearings, it fell to Sonia to appear on behalf of Mormons for ERA. Sonia later called it “a great moment in history” when, much to the delight of somnolent TV cameramen, Orrin Hatch “put on his priesthood voice” to rebuke her, and secured in one act all the TV coverage the Mormons for ERA had been vainly trying to attract. Even if her words had been mildness itself, her appearance would have been enough.

But they were not mild. Although she characterized the early Church as progressive about women—”in the forefront of the equal rights movement”—and went on to bolster her arguments with quotations from Brigham Young and James E. Talmage, she warned her listeners that modern Mormon women have been depressed and impressed into service long enough, and that women—Mormon women included—are rising, with the spirit of God as their motivating force. “She is bound to rise, and no human power can stop her,” she concluded.

Orrin Hatch, who is always news, focused the media attention on her in a way that was to have debilitating consequences for the Church’s public image.

From August to November the Mormons for ERA were more visible as they marched in parades and showed up unannounced at the Relief Society organizing meeting at the home of Clifford Cummings in early November. “When President Cummings organized that awful meeting, I knew what the women’s movement was all about.” The latest letter from the First Presidency had suggested that members work with other groups to defeat the ERA. The Oakton Stake leadership did more than that. It founded its own group, the LDS Citizens’ Coalition, with Beverly Campbell as anti-ERA spokeswoman. The group had been moved from the stake center after Hazel Rigby called President Cummings about the impropriety of holding a political meeting on church property. Julian Lowe, always the reluctant leader on this issue, made it clear that he was worried about the effects of the coalition on those stake members who disagreed. When the women of the Relief Society met to be taught lobbying tactics, Teddie Wood warned them that they would be con fronting their pro-ERA sisters in Richmond.

The question of when “anti-ERA rhetoric first translated into anti-ERA action” (to borrow a phrase from Sillitoe and Swensen’s Utah Holiday article) has still not been answered. Local leaders clearly had the blessings of central church leaders, but when Elder Gordon B. Hinckley of the Special Affairs Committee met with Regional Representative Lowe and Stake President Cummings, was it to organize or simply to bestow blessings? Questions about whether or not participants should be set apart for their jobs, whether or not petitions should be allowed in chapels and whether or not the group should register as lobbyists were also clouded in confusion. It seems to have taken the Oakton Stake quite a while to arrive at the ground they and the rest of Church occupies now, one where church members are unashamedly campaigning for issues now deemed “moral” instead of political.

Meanwhile, anger was building in Sonia’s ward. She was called in and questioned by her bishop about her part in a possible “Mother in Heaven” cult, and about a rumor that she and Rick had struck a member of the newly formed coalition.

1979. Richard leaves for Liberia for six months. “Mormons for ERA are Everywhere” banner flies over April Conference; Sonia gives her “patriarchal panic” speech (September); Sonia gives her “savage misogyny” speech (October); Sonia is quoted around the country as having advised her audiences to turn away the Mormon missionaries; Sonia meets with Bishop Willis in a “pre-trial planning session” (November); Sonia is excommunicated (December). Sonia and Rick are divorced.

Sonia’s speech to the American Psychological Association in September must have sounded mild to that audience, but it electrified the Mormons who read it. No longer quoting safely from the prophets, she had appropriated the word “patriarch” in a way that easily translated “priesthood” in the minds of her Mormon audiences. She also warned her non-Mormon audience against Mormon undercover agents too unethical to admit to their church-sponsored lobbying activities. Using colorful terms like “mindbindings,” she informed the world that the men of Zion were hiding behind the skirts of their women lobbyists. “What really got me,” she said in an interview, “was that our leaders were telling the women to say that they were not Mormons.”

Since Bishop Willis declines to be interviewed about his feelings and actions at this time, we can only guess at his sufferings. As a young bishop he was reportedly concerned about authority in his own young ward, he was pressured to “do something about Sonia.” By the time she delivered the famous “savage misogyny” line, picked up by the newspapers and delivered to his door, the die was cast. When he called her in and showed her a folder full of clippings underlined in yellow, she “felt a stab of fear. For the first time I wondered if I might actually be excommunicated.”

Events from then on have been well-documented in Utah Holiday, news papers and other magazine reports. The Church’s side was told mainly through press releases and interviews with Beverly Campbell and Barbara Smith. It seemed somehow fitting that Sonia’s trial would be as public as it was since her “sins” were committed mainly as public utterances. Whispered innuendos that she may have been guilty of heinous private crimes proved unfounded. Many felt sympathy for Bishop Willis, suddenly blinking in the glare of the spotlight, unable to tell his personal story and being portrayed as a sinister CIA agent. “But,” said one of Sonia’s witnesses, “I would have a lot more sympathy for Bishop Willis if I had not with my own ears heard Sonia offer to repent of her words and seen him refuse her.”

Sonia was to say over and over again that she had offered to repent, that the only thing she cared about was getting the ERA passed, that she was not advocating the overthrow of church leadership nor even the awarding of the priesthood to women.

Just before the trial, Rick Johnson returned from Liberia. He had previously written his wife and begged her to join him because he had been offered another overseas appointment. For the first time, Sonia refused. Six weeks later he asked for a divorce. She was coping with the shock of this when she heard herself read out of the Church. The public assumed that her political life had driven him away. She was uncharacteristically silent as to the real reasons for his departure, but she maintained that the ERA had nothing to do with it. When he too was excommunicated, reportedly at his own request, she took over support of the children and the ownership of the house in Virginia. Only much later did she connect her refusal to go to Liberia with his defection. When push came to shove it was his career that mattered.

1980. Sonia begins a busy round of TV, radio and personal appearances, telling the story of her excommunication and campaigning for the ERA. Her appeal is refused by President Earl Roueche and the Oakton Stake High Council; her appeal to the First Presidency is also refused. Sonia signs a contract with Doubleday to write her life story; refuses the First Amendment Award from Playboy; participates in civil disobedience; chains herself to Republican National Headquarters and the Seattle Temple gates; and spends a few hours in jail.

Sonia’s biting humor and flair for the dramatic captivated non-Mormon audiences like the Women’s Political Caucus on Capitol Hill, but it infuriated some Mormon women who heard her and reported it to local officials. Earl Roueche, after conducting a private review by the high council, refused to rehear her case. “I really lost respect for the men in the Church,” she said at that time. “Not one of them defended me. Not one! If only one had read to them from the Doctrine and Covenants, the rest of them would have had to hear me. Why didn’t somebody ask where I was when they held the hearing? Why didn’t somebody say, ‘Wait a minute. Where is Sonia? Why isn’t she here?'”

When she was later summoned to the home of President Roueche to hear a letter from the First Presidency, she knew that that which she had greatly feared had come upon her.

With husband and church gone, she turned more avidly to the public, those 50,000 people who, she says, love her. When Playboy Magazine presented her with their First Amendment Award, she kept the plaque but returned the money—$3,000.00. She said that she could not accept money made by exploiting women in a magazine that portrayed men and women in non-loving relationships. This plaque was only one of many awards she received during the year.

A reminder of what Sonia’s friends call her never-failing naivete surfaced when a telegram came from a famous television personage. “Who is Alan Alda?” she asked in puzzled tones.

Maida Withers marvels that during this time Sonia persisted in seeing her fame as so fleeting that she refused to install a second phone to catch the myriad of calls from the press and public or to seek help in answering the voluminous correspondence that was collecting in stacks all over her floor. “People think she was using the media or that the media was using her. She thought it would all blow over in two or three weeks; that’s why she refused to put in another telephone.”

During 1980 Sonia continued to assert her “Mormon-ness.” The lack of support that she perceived from such groups of Mormons as the Dialogue editors and especially the Exponent II women hurt her. Meanwhile, she was being discussed all over the Church in terms of fear, loathing and not a little ignorance. The most credible work done on the case by Mormons was the article by Linda Sillitoe and Paul Swenson in Utah Holiday. Sunstone published another piece by Sillitoe; the New York magazine Savvy published an account of Sonia’s life and travails by Chris Arrington. Throughout the Church she was developing into a folk figure of sorts, almost as ubiquitous as the Three Nephites. She became a litmus test of loyalty on the one hand and a symbol of the revolution on the other. According to Maida Withers, “The Church perceives her as an isolated character picked up by the media, but I see Sonia as only a participant in a movement, one that has been gathering really for centuries. Women are going to take a new place in society. When the Church took the unfortunate actions it did, of committing money and organization to defeat the ERA, the stage was set for one or more Sonia Johnsons to step forward on behalf of themselves and other women.”

1981. Sonia finishes her book, to be published in October or November; she begins attending church with her children at the local Unitarian congregation; she con tinues to support her family through public appearances.

Whereas a year ago Sonia Johnson was still proclaiming allegiance to her Mormon roots, in 1981 she announced that she will probably not return to the Church. She has given up her belief in the One True Church and is searching for a church where her children “can grow up with decent attitudes toward women.” She would like to spend the rest of her life pleading the cause of women; she doubts that she will marry again; she thinks she can make peace with her family; and above all, she is concerned with the poverty stricken women of the world.

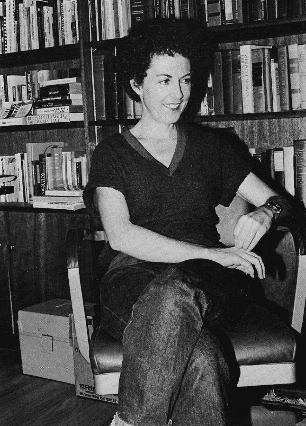

At the end of her nomadic odyssey, the question “Who is Sonia, what h she?” still provokes likely discussions at dinner parties and study groups. “I think they excommunicated one of the really true and honest, best Mormon women I’ve ever known,” says Hazel Rigby. One cannot help but lament the loss of this zealous, educated, difficult woman whose oratorical skill got her into trouble. She has used the word “orator” in describing herself, and it is apt. This image was bequeathed her by her father and is congruent with her performance. A reporter’s dream, easy to quote, her public utterances lend themselves to the time-honored proof-text method as well. Officials at BYU had no trouble picking out lines from her speeches in a way that left no doubt in the minds of most students that here was a true “rebel, heretic, a thing to flout,” a useful scapegoat for years to come. Sonia’s extensive education as well as her experiences as traveler and teacher clarified her natural gifts. Literary and historical martyr images were used to describe her, and indeed she applied them to herself—Hester Prynne, Ann Hutchinson, Joan of Arc. Now, almost two years after her excommunication, the images she chooses are revolutionary heroes like Patrick Henry.

Her journey can be traced and understood only through her speeches, public and private. For hers is an oral style, incomplete without the illustration of her body language and expressive voice. Though Sonia and the other members of Mormons for ERA always maintained that their whole argument was with the Church’s political stance, they early used emotionally charged religious motifs. The minute Sonia herself used Mormon religious vocabulary to defend her political stance she stood accused. By the time she had delivered her “patriarchal panic” speech to the American Psychological Association, she had stopped resembling a typical Sacrament Meeting speaker with dutiful footnotes from church leaders and had sounded the oratorical cry that would be her constant theme: Patriarchy.

Some analysts argue that she misunderstood the word and its nuances, that by misusing a word that in the minds of most Mormons is a benign term, she was treading on dangerous ground. Some believed she had borrowed from Marilyn Warenski’s Patriarchs and Politics, published during the beginning skirmishes of the ERA campaign, a title which was probably coined by the publishers. Though Sonia always claimed that she didn’t mean “priest hood,” and that she meant “patriarchy” in a strictly political sense to refer to man’s inhumanity to women, words deemed sacred to Mormons—”patriarchal order,” “stake patriarch,”—seemed suddenly tainted. Many Mormons thought her use of these terms spelled apostasy.

In the APA speech, Sonia piled up a list of oppressive measures visited upon Mormon women over the years, including “encyclicals from the Breth ren which took away women’s right to pray in major church meetings.” She further intoned that women had been “bootlickers and toadies to the men in the Church.” She warned her hearers that although priesthood was not her issue, some Mormon women were getting ready to demand it for themselves. Is it any wonder that the image of a female Joshua took root in people’s minds, the trump being the sound of her own unmistakable voice?

Those who heard Sonia in person were usually aware that her harsh words were tempered by humor. Her “Off Our Pedestals” speech the next month was funnier and less militant, and the readings from letters she had received from Mormon women blunted the sarcasm. “Mormon women,” she said, “all have the same goal: growth and eventual godhood for all the children of God.” But this same speech also included the ill-fated “savage misogyny” line. Hers was a rhetorical style that rallied some but repelled others. Hers was a style that left no one unmoved, and church leaders moved to blot it out.

It is tempting to play the armchair psychologist, to analyze the mind of this true believer of impeccable pioneer heritage and extreme fortitude. Did she feel the need to rebel against the father who gave her much of that fortitude but always worried about what her actions would do to his reputation, a father she perceived as “punitive?”

“I always wanted to be just like my mother/’ she says, “and so that must be the reason I’m not.” She describes her mother as a woman who never raised her voice but was so strong that one of her sons once accused her of “wearing the pants in the family.” Her mother’s deep commitment to fasting, prayer and visionary experiences succored Sonia and helped her survive. It is tempting to speculate: if her father had been as nurturing and approving as her mother, would she have felt the need to overthrow the fatherhood of the Church, or would she have been content to work for change within the system? On the other hand, suppose Bishop Willis and the other church leaders had avoided playing the part of the punitive father? Suppose they had been able to forgive her, even to be satisfied with disfellowshipment (which may have deflected the intense media coverage)?

This cursory look at the odyssey of Sonia Johnson seems to show that when she finally said to Richard Johnson, “Whither thou goest, I will not go,” she was paradoxically preparing to begin yet another journey in her nomadic life. In so doing, will she disappear from sight, a passing one-woman show, or does she represent other wanderers now eager to leave the hearths of their homes and churches to seek their religious and political fortunes? Only time will tell.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue