Articles/Essays – Volume 18, No. 3

The Only Divinely Authorized Plan for Financial Success in This Life or the Next

Thelm, the man is standing in his own way. If only he would get the vision of this thing. . . . See the potential, the tremendous opportunities. If he’d just drop those skeptical blinders long enough to see what’s really going on in this world. . . .” Carmen Maria Stavely, whose exotic given names trailed a deliberately homespun life like forgotten party streamers, raised both imploring hands from the breadboard on her kitchen table. There were traces of dough, like vestigial webs, between her fingers, and a haze of mottled beige flour softened her angular white forearms and conservative, pinstriped hair as though she had been airbrushed into her genteelly dilapidating kitchen by Andrew Wyeth. Her voice, however, and her adamant gun-metal eyes remained as impermeable and abrupt as broken slate.

At the far end of the table, her friend, Thelma, silently mixed and measured ingredients with that vaguely desperate preoccupation of the inept. It was some seconds before she realized that Carmen had ceased to knead the dough on the table in front of her and was poised over the breadboard as if it were a pulpit.

“Nineteen months, Thelm. Wednesday, it will be one year and seven months to the day that Walter lost his job. And he didn’t just lose it, either. He threw it over, threw it right in their faces like a dirty rag, because . . .” Her eyes retreated a little. “Because it was a matter of principle. And nobody understands any better than I do, Thelm, or than you do for that matter, that you have simply got to live by your principles. Walter turned round and walked away from that place, and he’s never looked back. And there’ll be no criticizing or second guessing from me or from the children. We know what went on down there. We’re proud of him.”

Thelma, who very much liked Walter, nodded earnest agreement, but was reluctant to smile or speak up. And her caution was her good fortune, for Carmen reversed field without warning. “I’ll tell you this. No matter what people say, you can’t eat pride. You can’t pay the bills with it. It won’t keep up with the mortgage; and when you get down to it, it won’t even help you hold your head up. Just you go down there to the savings and loan, or the gas company, or even the hardware store and tell them that you’re not going to pay again this month because ‘you see, sir, it’s all a matter of principle, sir,’ and then you watch and tell me how high your head is when you come out again. I’ve been apologizing to those go-fers of Mammon for nineteen months, so don’t anyone tell me about pride. I can’t afford it. I’ve got six children, and I can’t afford it.”

This was not like Carmen. Though she kept precise accounts of the world’s evils, when she spoke of family, she was normally as partisan and as carefully sweet as the Avon lady. She had not spoken like this with friends before, certainly never with any of the ladies from church. But Thelma, who was new, was also different. She was not a talker. Instead, from long habit and by genetic predisposition, she was a woman talked about.

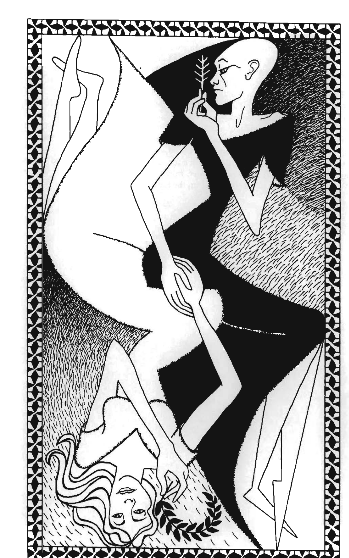

Since her early teens she had been indentured to a body whose breathtaking and bountiful femaleness was itself a destiny, so that for decades she had exerted little more than damage control over her own life. But now, at last and inevitably, her earthly vessel had begun to run awkwardly aground on the sands of time. And though she made use of this shipwreck to free herself and change the course of her life, she was none the less like the last surviving priestess of some razed and discredited temple who continues from blind habit — and the inability to do otherwise — to practice her ancient custodial art upon the ruin. She wore her dyed hair in the electric hues and styles that once made Rhonda Flemming’s fortune. And her floral print dresses were as dumbfoundingly a-domestic as her open-toed pumps and violet nail gloss. Sitting in church, she was a vision of transcendental cheek, an aging child of Babylon come in cheerful obliviousness to winter on Mount Zion.

And so the congregation talked. But despite their talking, she came. And if the truth were known, she came with a will. For though spectacularly out of context and as foreign as garden compost to the carefully aseptic practices of piety, Thelma Hunsaker Rydell had come among them to take not her place, but refuge.

Perched now in Carmen Stavely’s kitchen, she was like a giant flowering lotus in a pantry herb garden. She dominated the room with flaunted color and inutility all the while she struggled with the bowls and cups and measuring spoons on the table before her. Carmen, however, seemed not to notice. The truth is that, though she loved to brandish the Lord’s terrible swift sword, she was not finally capable of pointing it at real flesh-and-blood persons. In her own way she was as incongruously innocent as her guest. The two had, in fact, become fast friends—more than friends, for each filled an acute need in the other. Thelma was the willing acolyte, a submissive and even anxious pupil in search of keys and passwords to a better and more peaceable kingdom. Carmen, on the other hand, was an incorrigible but seriously disheartened teacher who very much needed a disciple possessed of eyes to see and ears to hear.

They read in the scriptures together, and Carmen explained at length, jealously shepherding her ward through the jungles of interpretation. She led Thelma gently but unswervingly by the pure light of orthodoxy as only Carmen understood it. And while she led her, she introduced her as well to certain other blessings: the consolation of natural herbs, the joys of honey, pure and unrefined, the regenerative power of legumes and of raw milk, and the open revelation of whole, home-ground wheat. And truthfully, all that she gave and all that she did for her new friend was repaid her an hundred-fold in gratification. For unlike Walter, who merely tolerated his wife’s sacrificial devotions to a higher order of nutrition, and unlike her children, who, she knew, cheated, Thelma embraced vegetarianism as sincerely and enthusiastically as if all along she had only been waiting to be asked. In the logic of her emotions, in fact, the surrender of flesh seemed a natural consequence, an ordained penance, and a modest price to pay for release from the past.

Together, the two women shared abstinence and enlightenment in growing communion. In the course of just a few months Carmen opened Thelma’s understanding to the first and last principles of history and of politics, of medicine and cosmetics, of nutrition and housekeeping and home economics. And on this particular day, because it was very much on her mind, and because only eighteen hours earlier a terribly important — and equally inconclusive — meeting had taken place in her own living room, Carmen rehearsed her pupil for the umpteenth time in the virtues of a certain superlative cleaning agent. It was — on principle — the only such product Carmen allowed in her home. The Stavelys washed everything with it from their teeth to their rusting Ford stationwagon, and Carmen hoarded an entire two-years’ supply in a basement cupboard no bigger than a bread box. Like other enlightened users, she rendered moral tribute to its pure and unfrilled utility by calling it simply “the product.” And, as with so many other things, her unwavering product loyalty was rooted in true religion.

“It’s concentrated, Thelm. That’s the whole thing. It’s absolutely concentrated. Do you realize what the women of this country are paying out every single day for useless fillers? A cup of this and a cup of that. Do you have any idea how that adds up? But no matter, they just keep pouring it right down their drains, right down the tubes, right down into the pockets of the corporations, the multi-nationals. And while those gangsters get richer and richer, what do we get? Well, I’ll just tell you. We get filler! Forty, fifty, sixty percent. . . it’s infuriating, absolutely infuriating!”

She pinned the glutinous mass under her small fists unrelentingly to the floured mat on the board. Then, releasing all at once, she looked up with resignation. “It’s our own fault, you know. Walter showed me an article in Newsweek. We don’t subscribe, of course. Those magazine people are all owned, body and soul, by the multi-nationals, and I won’t let him. But he buys it at the drug store anyway, and I guess I don’t mind as long as the money doesn’t come out of household, and he doesn’t leave it lying around for the children. Sometimes, I think they even print the truth in there — when it serves their purpose. I think this was the truth, Thelm, because this company did a test, a marketing one, and offered genuine, pure concentrate to the public. Imagine! And do you know that 73.2% of the women tested — seventy-three point two! (Carmen was addicted to dramatic repetition) — paid no attention at all to the directions on the box. Bright red letters, big as you please, and women went right on pouring a cup of this and a cup of that until their machines choked up like stuffed zucchini. And the cost, well it went absolutely through the ceiling, and the first thing you know they’re all clamoring to the corporation to ‘please’ let them have their fillers back.”

Pain settled over Carmen’s high alabaster brow like the mark of Cain. “Can’t you just see it? Can’t you just visualize the chairman and the smart aleck vice president of sales slapping each other on the back and gloating all over the board room? If that story doesn’t just have the clarion ring of truth to it. You should have seen Walter. Couldn’t have been any more pleased if he’d thought it up himself. Oh, he didn’t say anything, but the silence nearly cost him a hernia. Dear Lord, is it any wonder that many are called, but few are chosen? When it comes to women, Thelm, sometimes, I confess, I think the fewer the better. Sometimes I’m not very charitable.” Deftly she reversed the heaving victim on her board and this time fairly slammed it down into the bed of flour which woofed out on either side and then slowly dissipated in magnified particles through the angular afternoon sunlight.

“I guess,” offered Thelma, now experienced enough to know a response was expected, “I guess they just didn’t understand the importance.” And then in a tone of concession. “I suppose it’s not very surprising, is it?” She was half apologizing, wondering if she herself were not guilty of having poured an unrecognized fortune in genuine concentrate through the glutted bowels of some hapless machine. More than one had succumbed to her prodigal stewardship.

Thelma was now separating dough into loaves and setting them aside to rise again. “How many are we making, Carmen dear?” She changed the subject with a decisive cheerfulness, hoping to divert attention from her own probable complicity in this sorry affair. And she watched with relief as her mentor’s quick mind tracked rapidly and systematically out of its distraction to lodge the question neatly into context. “Thirty-six. They want thirty-six this time. We’re a great hit. Especially the honey-cinnamon. Brother Glover is printing up new labels right now. Every single ingredient listed in big old fashioned letters right across the top, and ‘Mrs. Stavely’s Natural Breads’ in fine print at the bottom. That was my idea. We can pick them up in the morning on our way to the shop.”

Carmen completed her final series on the bread board stylishly with a double underhook and an improvised guillotine of artful wickedness. “There! And they are paying us right up front this time. Just like downtown.” She relished this acquired bit of business-speak, though her anxious mind was foraging far ahead of the pleasure. “But it’s not enough, Thelm. It’s never enough, and it’s gone before I ever see it. Walter has simply got to see the light.” The sun percolated from her mood again. “He’s fifty-four years old, and they’re not hiring account executives at the old folk’s home. What is the man thinking of? Last night in that living room out there, right in front of witnesses who’ll swear to every word I’m telling you, Kevin Houston offered my husband a distributorship — a dis£n’6utorship, Thelma.” She paused to underscore the inconceivable. “And Walter behaves as if he were deaf .. . or crazy .. . or senile! Did he say, ‘Yes sir, this is the chance we’ve been praying for?’ Oh no! He didn’t even say no! He just embarrassed me and seven perfectly unsuspecting people to death, that’s all. I could have choked him. I could still choke him.”

Thelma tried to reflect appropriate distress. She knew Kevin Houston. He taught Bible classes every Sunday to overflow crowds of hushed and wet-eyed admirers. More importantly still, he was known to be the young wizard behind the organization that sold and distributed “the product.” He was a much heralded, much-admired, phenomenal success. And he was not secretive or niggardly with his magic either. There were meetings, seminars with flip charts and flow charts and ardent testimonials; and Carmen Stavely went, more willingly almost than to church, for she returned truly encouraged and up lifted. But her unemployed husband would not go with her; and so, Thelma guessed, she had resolutely brought Mohammed to the mountain, though apparently with disappointing, even disastrous results.

Thelma hurt for her friend. Yet her sympathy taxed her scruples because, if the truth were known, she did not entirely like Kevin Houston. At first she had credited the unwelcome shadow of aversion to his wife, a tall, dental red head, who smiled and popped her gum with the steely self-assurance of a knuckle-ball pitcher. But it wasn’t his wife, it was Brother Houston himself, though the reason was hard for Thelma to put her finger on. Perhaps it was the involuntary way he courted women, his pure adolescent sincerity, the vulnerable eagerness to please; or perhaps it was the ready masculine command over every needful and unneedful thing. He was a charming show-off, not unlike certain other remarkable men she had known, and not known, and, unfortunately, married. In his presence, she felt uncomfortably at home. And if she followed and listened to him as enthusiastically as anyone, it was never without a troublesome pang of self-betrayal. But these misgivings were still vague and beyond Thelma’s capacity for articulation so that when she came, as she felt she must, to Walter’s defense, she had little choice but to travel on borrowed light.

“The Potters say they’re not going to get involved with Brother Houston, because his business is what you call a pyramid scheme. Maybe that’s what Walter is thinking, dear. Maybe you shouldn’t be getting involved in a pyramid scheme either.” Thelma knew she was in over her head, but the open scorn that blossomed in Carmen’s face told her she had trodden on something ripe and dreadful.

“Sylvia Potter is as dim as dusk, and so is her husband. Of course it’s a pyramid, Thelma. What else would it be? Now, you just get out a dollar bill and take a good look at it.”

Thelma, though readily contrite, did not have a dollar; and Carmen rummaged angrily through her cupboards until she found one, then spread it out dramatically under the nose of the blushing lotus lady at her kitchen table.

“Now, what do you see?”

Thelma stared blankly down at the bill.

“Oh, for heaven’s sake, not there!” Frantic with irritation, Carmen reached down, flipped the bill over, and pointed. “Here!”

Thelma was astounded. “Why, it’s a pyramid.”

“Of course, it’s a pyramid. And what does it say right there?”

The words were Latin, but Thelma obediently mispronounced each in turn as it was pointed to, and then, when she had finished, Carmen translated the lot just as if Latin were as familiar to her as the Reader’s Digest: ” ‘God’s new-order-of-the-world-now-established-among-men.'” Carmen completed a second instructional pass round the pyramid with her finger. “It’s God’s own plan, Thelm, put here in a free country with a free market and free enterprise. That’s what a pyramid is, it’s capitalism — Christian capitalism — and it’s there because the founding fathers of this country, men like … ”

She flipped the dollar bill over once more and poked with her ringer until Thelma read, “George Washington.”

“Exactly! Honorable men like George Washington, whom God raised up for that very purpose, put it in the Constitution and on the back of that dollar bill so that every eye might see and every tongue confess the truth of what I’m telling you right now. Of course, it’s a pyramid! Anyone with any education and any proper history and common sense knows it has to be a pyramid, because that is what this country is all about. When you’ve got a pyramid, you’ve got the only divinely authorized plan for financial success in this life or the next.”

Carmen drew herself up on the table and was very solemn. “There are laws, Sister Rydell, decreed before the very foundations of this world, and if a man wants any blessing at all in heaven or on earth, then he’ll only get it through obedience to the law on which that blessing depends. And when Kevin Houston offers you a distributorship in your own living room, it’s not just some business he’s talking about. It’s a corporation in the very image of the eternal. It’s an executive position in the new order of the world. And that’s an investment that thieves can’t steal nor moths, nor rust, nor anybody else corrupt. That pyramid scheme, you’re talking about, is an answer to prayer, pure and simple. Last night Kevin Houston offered my poor drowning husband a steamship, an entire, luxury steamship. And it’s so big and so marvelous and so absolutely beyond imagining that Walter can’t even see it. He’s as blind to it as a dug-up mole to sunlight, and if I don’t find some way to open his eyes, then he and I and the lot of us are going to go down right here in plain sight of rescue.”

Thelma was by now well aware of just whom she had inadvertently provoked. She recognized the vocabulary and the high, dramatic, sabbath school tone. “What,” she asked defensively, “did Walter say when Brother Houston made his offer?” And her tactic worked, for Carmen ignored the question entirely, though her uncharacteristic silence made it obvious that it oppressed her. She was already stacking bowls and pans and filling the sink with water, but sooner or later the burden would have to be excised from her narrow chest. After a moment or more of struggle, she opted for sooner.

“Do you know what he said?” She turned with both anger and incredulity in her voice. “He said, ‘Young man, your fly is open.'” Thelma choked and struggled for control over the involuntary muscles in her diaphragm.

Carmen, meanwhile, raged. “That’s it! The whole thing! The exact words! An hour, an entire hour spent explaining the program, step-by-step, right out of scripture so any child could understand. And all Walter Stavely sees is an open zipper. It’s disgusting. In front of all those people. I’ve never been so embarrassed in my life. And poor Brother Houston didn’t even have time to turn around and zip himself up before Walter hightailed it into the kitchen like some scamp child who knows he’s in for the dickens. If I were his mother instead of his wife, I’d strangle him.” She went back to her dishes. “And what am I going to tell Kevin Houston? The man’s a Samaritan . . . there’s no other word, a Samaritan. ‘An offer’s an offer,’ he said, just as if nothing in the world had happened. But whatever am I going to say to him when he calls this evening?”

“Can’t you take the distributorship yourself?” Thelma abandoned Walter to his fate. But Carmen kept to her dishes and replied as automatically as if the words were memorized. “Walter Stavely is the head of this family. It’s his responsibility. It’s his decision, and he has got to make it. If you cut off the head of the family, Thelm, you kill the body too. Some solutions are just no solution at all.”

“Well, have you asked him?” Thelma persisted.

“Yes, of course I have. This morning. Out there in the garden. He was tying up those tomato plants again, though it’s so late in the season, I don’t know why he bothers. I asked him straight out, ‘What do I tell him, Walter. I’ve got to give the man an answer.’ ”

“Well?”

“Well, he looked up grinning like a bad joke and said, ‘My dear, the man’s a flasher, and I never go into business with flashers.’ ” Thelma choked again, but Carmen hadn’t finished. “Now flashers are not necessarily bad people. Walter wants that understood. In fact, they have a certain basic honesty — very up front, so to speak. Isn’t that clever, Thelm?” Thelma was paralyzed, unable to raise her eyes from the table. “Don’t you think that’s very clever of Walter? Sat out there all morning thinking up his clever answer. And when he’d given it, he looked at me with his old man’s eyes and said, ‘I’m sorry, Carmen. I suppose he’s a nice enough fellow, and, yes, he knows a thing or two about the world, but I promise you, that young man will show you things you never wanted to see.’ And then he went back to tying up those damned tomatoes just as if he’d really said something . . . and just as if those poor exhausted plants would go right on bearing all winter long, and the mortgage wouldn’t fall due, and the roof didn’t leak, and the transmission in the stationwagon wasn’t going, and Kathryn and Walter, Jr., didn’t need help with their tuition, and the final insurance notices weren’t out there unopened, because I can’t face them, and the water bill, and the taxes . . . .” And her voice trailed off into a litany without shore or boundary.

A long time passed. The afternoon dissolved into autumn gloom, and Thelma realized with a start that her teacher, her sure-minded, millennial sponsor, was sobbing quietly into the dishwater. She sat for a while in self-conscious silence, unsure of what to do, but in the end her instincts were stronger than her brief acquaintance with discretion. She went to Carmen Stavely, folded this narrow, bristling bird of a woman into the schooled softness of her great, fading, vagabond bosom, and held her like an older sister or like the mother she’d never been, while her friend cried helplessly, and God on his inscrutable pyramid sent raw winter rain down upon the very spot where Walter Stavely had so carefully tied up the tomatoes.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue