Articles/Essays – Volume 23, No. 3

The Playhouse

I sit scrunched in a fetal position, my eyes tightly closed, savoring the womblike comfort of the playhouse. A spider is weaving its filmy home in one corner of the ceiling, and a fly has buzzed to its demise against a warm plastic window. I don’t mind sharing this place with the insects. I come here often when the kids are in school, just to sit and think and pretend I am a little girl again. Grampa built my older sister Gladys and me a house like this when we were young and eager visitors to his farm, a cozy country place complete with horses, cows, pigs, and chickens. We were the first grandchildren; and since Mama traveled a lot following Daddy during the war, we were consequently taken over by my doting grandmother, who spoiled us and dominated most of our upbringing.

Grampa made our playhouse fancier than this, though, with gingerbread trim around the eaves, real glass windows that slid open, a pretend sink, and little knick-knack shelves with rounded ends and covered with countertop just like Grandma’s.

I needed that playhouse. It was my refuge, my harbor from fear, my last resort. It was my security, because Uncle Ed could never get me there. No matter where else he came for me, he could never come in my little house. I felt protected, like a mouse in her mousehole.

I don’t know why he never came there. Maybe he felt foolish walking the distance to the end of the orchard where the playhouse was, stooping to enter its child-size door and maneuver around child-size furniture. Or perhaps its windows on all sides repelled him with his need for privacy. Or maybe, strangely enough, he thought it sacred, like the temple, not to be entered by people like him.

He didn’t think me sacred, though. And there were other places where he had no second thoughts about intruding to satisfy his special needs. Like the enclosed staircase behind Grandma’s kitchen where I played with my paperdolls, or the sewing room where I slept when I got to stay weekends, or in the darkened living room under a pillow as he sat me on his lap. Or the oat field.

I remember vividly the oat field encounter. I had just turned seven that week, and Grandma had invited Gladys and me to the farm for a few days as a birthday present. It was a lazy midsummer afternoon, and we had gone out to pull mustard weeds for Grampa. I loved being in the fields then, when the sky was terribly blue and there were no clouds, and this day was particularly delightful. We skipped merrily across the pasture in cool blouses and jeans, feeling as fresh and new as the tender green oat plants. Our assignment was to pull the yellow flowered plants from the damp earth before they went to seed and ruined the fall harvest. We got hot and sweaty as we competed for the biggest bundle of the sour-smelling weed, and we laughed and raced around, crushing some of the oats in our exuberance.

But just as we finished, I looked up and saw a thin, dark figure coming toward us from the house. Though the sun was behind him and I couldn’t see him clearly, I instinctively knew it was Uncle Ed. And I knew why he was coming. My hands went clammy and my skin turned cold.

When he came up to us, Gladys joked and played with him for a while, but then she got tired and went in. I tried to go, too, sticking very close behind her, as if by some chance he’d forget about me. But he didn’t. He held me back, squeezing my shoulders. I struggled and thrashed anxiously, but he only gripped harder, hurting me, as Gladys skipped ahead. I wanted to scream, “Come back, Gladys, come back! He’s going to touch me!” But I couldn’t. I was afraid he would hurt me; and besides, Gladys wouldn’t understand.

He waited a few minutes to make sure she had actually gone inside, looking nervously around the field and holding my arm so tightly it cut off my circulation. Then when he knew it was safe, he carefully crushed the grass all around into a soft nest, like a large animal going to sleep, and gently pushed me to the ground. His clumsy hands hurriedly undid my buttons, shoelaces, and zipper, his breathing growing heavier as he completed his task. And then his huge frame crushed down on me. I shut my eyes and tried to pretend it wasn’t happening, but then I opened them and saw his face contorted and straining. And I knew it really was.

When he finished, he dressed carefully, dusting off bits of grass and dirt from his pants, adjusting his belt, and tucking in his shirt immaculately. Then he took out his comb and made sure every hair was in place. As he did so, he sat a little apart from me and looked away, almost embarrassed, like he had just found me there and had had nothing to do with my awkward condition. My hair was filthy with dirt, my jeans stained with grass, my body sticky. My glasses were somewhere on the ground. Then, as if by some secret sense, an unspoken, ominous pact went between us: “Uncle Ed didn’t do anything.” I got dressed without looking at him and scampered away like a scared rabbit.

I didn’t go the farmhouse where Grandma was baking cookies, but to the playhouse, where I could turn for a few minutes into a grown up. I smashed handfuls of raspberries into jam on a plate, splattering juice all over the counter, not caring about the stain. Then, leaving it to ferment under the shelf, I huddled on the wooden bench by the window, wanting the late afternoon sun to warm me. It didn’t. I was chilled, from the inner marrow of my bones, to the top of my head, to my feet. I turned numb, blank.

I don’t know how long I stayed there; but near dark, I went back to the farmhouse. Grandma was cooking Swiss steak from the steer Grampa had butchered last week, and the kitchen smelled of beef gravy and seasoned salt. When Grandma saw me, she turned from the stove to hug me. “There you are, little honey! Where have you been? Are you feeling okay? Here, go and put these on the table.”

I dutifully set knives, forks, and spoons on the Quaker lace cloth, all the while feeling his hands on my body and wondering if I should tell Grandma. But she loved Uncle Ed so much, I didn’t think she’d want to know. I guessed that she didn’t want to know the answers to those “how are you feeling” questions either, because she never looked into my face like she cared. They were just questions without question marks.

The oat field wasn’t the only place I couldn’t hide. In fact, when I stayed during the week, I never felt safe until he was on the bus going to high school. I’d sit on the big window seat behind the dining room table and watch the bus roll up to the house, and Ed would get on with his sack lunch. Then I’d run upstairs to the attic where he hid orange crates filled with Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck comics that we weren’t supposed to get into, and lie on Mama’s old bed and eat cookies and read all morning and Grandma didn’t mind.

But I never could look into his room across the hall or go inside without getting sick to my stomach, because that was where it started. We were sitting on the edge of the bed in front of the mirror, and I was on his lap. “Where do you want me to tickle you?” he kept asking gently, over and over. I saw myself smiling back at him shyly, trusting him, loving him, with shiny baby hair curling at my ears. I looked so young in that reflection.

If Uncle Ed was the devil of the upstairs, Grandma was the angel of the downstairs. She was well known for her cooking and organizational abilities and used her talents to spread love and good will among the community. Ever the typical sweet Mormon matron, she taught me to love the gospel as she held my little hand in hers every Sunday and boomed out, “There Is an Hour of Peace and Rest,” making her scratchy voice go high and wide on the “boon.” I loved the “boon,” and I loved her. I treasured our summer days together as we kneaded huge mounds of brown bread, searched for new eggs in the henhouse, and hung up damp, sweet-smelling flags of sheets and workclothes on the lines out in the orchard.

She was one of the pillars of the ward back then. Relief Society president and homemaking leader since time began for me, she organized and produced the yearly Swedish smorgasbords that netted the ward a brand-new building. Posters all over town advertised “over fifty authentic Swedish dishes.” The event was held in the local high school cafeteria, where Mutual girls served as waitresses in starched organdy aprons and passed out crumb pie and fruit soup. I loved the hustle and bustle of these galas, with hundreds of noisy, hungry people leaning over long tables piled high with Scandinavian bounty, and the annual argument between Grandma and Brother Beukers over how thin the turkey should be carved. I could eat free and stuffed down pickled herring, meatballs, and rosettes to my heart’s content.

At Grandma’s funeral, the stake president spoke fondly of those times with Grandma and said that they had been one of her greatest missions in this life —that she had been sent to earth to use those talents for the furthering of the kingdom.

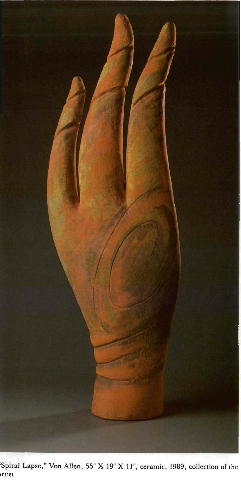

The irony of it all was that she raised a man like my uncle. Uncle Ed was not only a highly gifted artist, but also the ward “funny man.” He was always drawing posters for roadshows, musicals, and talent shows and then acting as emcee as well. He could stand in front of his audience without a hint of a smile, tell jokes that made people fall over in their chairs, and still keep a straight face. He could find a laugh in anything. He would take a remark or a topic somebody had brought up, twist it around, and make it into a piece of comedy. We grandchildren and cousins dubbed him our “funny uncle.”

When he wasn’t doing his comedy routines, he was sculpting, twisting clay noses into shape, poking eyes deep into soft heads, squeezing necks into proportion. And when he wasn’t doing that, he was tickling everybody. Tickling all of us grandkids with those delicate artist’s hands, touching us hard, probing and squeezing and hurting when the grownups weren’t watching. Uncle Ed tickled us until we cried, but he tick led me most. I would laugh because that was the way my child’s body reacted, and I was in too much pain to be articulate, although I wanted to cry out, “You’re torturing me!” Instead I could only giggle, “Stop it! Stop it!” over and over, but he never took me seriously and went on and on until only my mouth laughed. He tickled Gladys once so much she threw up, and I wished I had too, all over him.

When he finished tickling everybody, he would single me out, pick me up and take me upstairs to his bedroom where he pushed a big trunk in front of the door. Then he got undressed while I sat on the bed and waited in paralyzed silence, like a trapped animal, knowing what was going to happen but not knowing what to do about it.

Oh, I fought sometimes. I tried to push him away when he came for me downstairs, shoving at his arms, clinging to Grampa in plain sight, hoping he would get my hints for help. But Grampa would just go on staring at his newspaper through his giant magnifying glass, absently chastise, “Eddie, stop roughhousing,” and gently nudge me away.

So then I’d run and stand between Grandma and Mama in the kitchen and cling to their chairs by the wood stove, but he’d pretend to play with me and lift me up between them, gripping my arm painfully where Mama couldn’t see, and gritting his teeth. I was terrified and let go, and Grandma would say, “Eddie, stop teasing the girls,” and turn back to her gossip.

Grandma wouldn’t have believed me if I had told her anyway. Eddie was her youngest, and he wouldn’t do such things. He was too good. Everyone knew she wanted him at home with her forever; and when he became an elder, he would be the head of the household, because Grampa was not a member of the Church and therefore not qualified in any respect, according to her. Any thoughts like that would be my perverted imagination. Grandma might stop loving me or not let me come to her house.

If Mama believed me, she wouldn’t like Uncle Ed anymore. In fact, she might hate him, and we wouldn’t come out here ever again, and our summers and Christmases and chicken every Sunday after Church would be over. Riding with Grampa on his tractor and feeding the cows in their stalls would end. There would be no more lining up for cookies from Grandma’s big old glass jars left over from Church suppers, and no more lying under crispy fresh-as-outdoors sheets with Gladys telling me stories, and no more helping Grandma wash clothes in her wringer washer, pulling them out like the flattened cats in Walter Lantz cartoons, and spending hours upstairs listening to “Old Prospector” records. Grandma’s house was our oasis from school and the everyday doldrums of existence in town, and did I want to ruin it all with one silly statement like, “Mama, Uncle Ed is putting his hands underneath my clothes and touching me and it scares me, and I don’t like it, and I’m afraid of him. And then he makes me hold him and he gets on top of me and after a while there is this sticky stuff all over me, and do I have to do this with him? Grandma, Grampa, Mama?”

My words could change the high-standing family of which Grandma was so proud, especially with Great-Uncle Howard being bishop and Great-Uncle Ray being stake president and Uncle Ed being Young Men’s first counselor.

At Primary we sang, “Little lambs so white and fair, are the shepherd’s constant care.” I never let myself sing it, because I knew I wasn’t one of God’s little lambs. Nobody constantly cares for me, I thought. Mama would have him drive me to ballet lessons, and he’d cover my lap with a newspaper to fondle me at stoplights. And I’d stand naked in front of the bedroom mirror with his hands on my genitals. Uncle Ed seemed obsessed by them as he manipulated my body. He was always silent and grim, with an impersonal look on his face like a mortician working on a cadaver. I tried to guess what he was thinking. Maybe he was pretending I was a beautiful girlfriend that he never had in high school; or a sex goddess from one of his Playboy magazines I’d see lying around when he did it to me. I’d hunt for them sometimes, when I was given the task of helping Gladys clean up his room for Grandma, when he was away. I’d look through the pages and get this dark, cloying feeling that made me want to throw up and have sex at the same time. It would captivate me and make me stop thinking of anything else except wanting to float away into outer space or be sucked into a deep hole. Finally I’d feel one of my headaches coming on, so I’d take a deep breath and run down stairs where everything was civilized and Grampa was hunched over the news on the radio, turning the sound up so loud you couldn’t hear anything else. I was relieved that life was being lived somewhat normally, if only by an old man who never spoke to me.

People wondered why Uncle Ed didn’t have a girlfriend, but Grandma said it was because he was so pure. Only evil-minded boys needed girlfriends, she said. Carol Johnson and Denise Richards chased him for years, but he always hid in the back room when they came over, telling us to say he wasn’t home. Carol said it was because he was shy, and Denise thought he couldn’t face up to reality, so she humored him and persisted in her one-sided courtship. On Friday nights Grandma would beg him to stay home with her because she was so lonely. He’d dutifully agree and drive down to the A & W and pick up a gallon of ice-cold root beer. Then she’d dress up in her red dress with the gold earrings and sit with him in the living room and drink root beer and watch TV while Grampa sat at the dining room table with his magnifying glass. I got to sit with them, and for once Uncle Ed didn’t touch me.

When it was time to go on his mission, Grandma told everyone he couldn’t go because he had a bad back. “Poor Eddie,” she’d say, “he just can’t do the things other people do.” I hated the way she protected him, smothering him with her huge breasts, making him helpless and dependent on her. “He is my last baby,” Grandma would say to Mama, tears gleaming in her eyes. “He is the only one I have left to love. When he leaves, my life will be over.” She had forgotten about Grampa.

I used to get angry seeing her so painstakingly, unnaturally save Ed’s dinner for him in the oven when he was all grown up and too old for it, not even knowing when he’d be home from who knows where doing who knows what. He’d just look at it stupidly and go and make peanut butter and jelly on white soda crackers that dripped all over the plate. The crumbs fell like dandruff into flaky white bits on the counter when he bit into them, and he’d leave everything for Grandma to clean up in the morning. I’d stay out of sight then, hoping he wouldn’t know I was there, but he’d come looking for me in the sewing room bed, and I felt his powerlessness turn into power at the sight of me. And there was no getting away in the dark house with everyone asleep.

The next week at home I’d spend hours daydreaming about having my own little girl to hurt and squeeze like he’d squeezed me, a real little skinny one, and I’d shake our cat hard until it was afraid of me, and only years later did I know that it was him I wanted to hurt.

Then one day, when Eddie had left home and was a sophomore living with a bunch of guys in a house off campus at BYU, there came a letter addressed to Uncle Howard, the bishop. They were expelling him for “perverse activities not in keeping with the standards of the Y and morals of the Church.” Even though Uncle Howard placed the letter in Grandma’s hands, she wouldn’t read it; and when it was read to her, she wouldn’t believe it. She just cried and said it wasn’t so. And so it wasn’t, because when Grandma didn’t acknowledge a thing, it didn’t happen. And that was that. Life just went on.

Maybe I didn’t happen either, I think grimly, bunching my legs more tightly under me, ignoring the increasing ache, wishing my arms could reach around myself again, although the playhouse has become hot and stuffy. It is as if I am reaching for some comforting thing just out of my grasp. Sweat drips from under my knees, and I am itching with its stickiness at the back of my neck. I remember the day I realized that the playhouse was the only tangible evidence that Grampa loved me, because he had never really talked to me. Startled, I called Mother with the exciting revelation. But if he loved me, why didn’t he rescue me, I ask myself over and over. Why didn’t he see? Why didn’t they all see?

One night when I was twelve, Mama and Daddy sat Gladys and me down for a talk about sex and told us that our vaginas are pear shaped and that we shouldn’t let anyone undress or sleep with us because the little seed might leap over to us and we would get pregnant. I tried to imagine a boy sleeping next to me in bed and a corn seed leaping over to me, and then I put things together with Uncle Ed and me. And I went into a cold sweat and thought I was pregnant; and every day in front of the bathroom mirror, I anxiously checked my tummy for swelling. I imagined myself sitting for months in an unwed mothers’ home, disgracing the family with my sin. I lived in fear for a long time, not knowing any details about the logistics of periods and that I wasn’t old enough to have one. Several times I came close to telling Mother, confessing before she found out, and hoping for clemency. But I never did.

Instead, I lived with my secret, unaware that Uncle Ed could not have made me pregnant with what he carefully did but not getting all the information I needed to come to the correct conclusion. And as time wore on and I did not get any fatter but saw myself growing tall and strong, my timid submission to Uncle Ed grew into hostility. I was about thirteen when he felt my new knowledge coupled with anger. It was a Sunday night after one of Grandma’s typically overladen dinners when the whole family was gathered companionably around the lace-covered dining table picking their teeth and eating too many cookies. They were trying to look polite as Grampa launched into one of his rare talkative moods telling disjointed stories about his Swedish childhood in the deep snow and how he stole a thick pancake in the army. Mostly everyone was yawning and looking at the table, and Grandma was trying to discourage him by chattering loudly to Great aunt Ethel about Relief Society problems. Ed padded around to me quietly and tried to take my hand to lead me out, but this time I was ready to defend myself, maybe even get revenge. I clenched my fists, glared at him, and sat rigidly, ready to fight. That was all I had to do, because he immediately backed off and never bothered me again. I heard many years later that he went for one of my young cousins, and then my baby sister Cynthia, who was three by the time he turned to her. How many others between times, I have no way of knowing. Finally in his thirties, he married my Aunt Reba in the temple and had eight children in ten years. I went to his reception.

At sixteen I made a conscientious effort to forgive him, to prevent myself from becoming so bitter and angry I couldn’t function. I had to pretend nothing had ever gone on, and he was visibly relieved at my charade. Then I began to hope, to believe, like I had learned in Mutual, that if I was pure and married in the temple, nothing bad would ever happen to me again. But that was for girls who hadn’t been molested.

I didn’t get married until I was twenty-six. I had rejected the two or three men who had asked me up until that time because I thought they were weak. Instead I chose a grim, stern, “strong” man who had been molested himself, who didn’t talk very much, and who told me what to do, like what to wear and when to stop eating. We traded stories on our mutual abuse, finding it odd that we should find each other. At first I thought our relationship was too good to be true.

But after we had been married two years, he became withdrawn and cold and resorted to satisfying himself with me in the bathroom in front of the mirror, businesslike, quietly, before he left for his Church meetings. Conversations consisted of his orders to me, which I always immediately obeyed. I began to sense that I had married another Uncle Ed. I became subservient, fearful, and anxious to please him so he wouldn’t get angry or hurt me. When he came home at night, the children and I hid in the back room to avoid his anger.

Late at night he would tease me by turning off all the lights in the house and telling me he was coming to “get me.” And he’d tickle me, too. I came close to a nervous breakdown; and after seven years of marriage, divorce was a relief.

In the middle of the divorce and the humiliation of having a big D emblazoned on my chest for all the Church to see, Gladys called. She said that Ed’s family of seven girls and one boy looked withdrawn and depressed, and she thought something was going on. Did I know anything that I should be telling her? I did, feeling it was right for the first time in thirty years. She told me she had suspected it for a long time but had never had the nerve to ask me. I was relieved, she was shaken, and we both became closer, talking for two hours long distance, com paring mutual suspicions and feelings.

In the ensuing months of investigation by the Church court, I was asked to make a statement to the high council; and as I did, I wrote Ed, too. I told him I forgave him, and said I still loved him and wanted him to be a part of our family.

I wanted him to say he was sorry and that he would never have knowingly hurt me. But he didn’t. He merely wrote back that I was incorrect, he hadn’t started molesting me when I was four years old, but two, and only because I was a “whining, clinging child.” Furthermore, he said he would have been a lot better off if he had just thrown me down the stairs. But hadn’t he loved me?

The court gave him a year’s probation in which to start paying his tithing so he could go back to the temple, because, they explained, it was so long ago that this had happened, and he had had it on his conscience all these years.

I wanted to grab his genitals, string them out, and chop them off, inch by inch. I wanted to rip his clothes off and expose him to the open sky like he had me and ask him how he felt. But now the whole world knows, including Mother; and everything I feared as a child has come true. Mother hates Uncle Ed, and Uncle Ed doesn’t visit any more, and we hardly know his family. His children don’t know why we no longer get together at Christmas, although we live only ten miles apart. Mercifully Grandma died not knowing. She loved him so much. Probably more than she loved me.

Uncle Ed looked so good at Grandma’s funeral. So young. He’s fifty, and he hasn’t aged a day past thirty-five. Aunt Reba brought their eight children and was even warm with me. But he wouldn’t come near me or Mother. I could hear him telling his jokes and the little groups around him guffawing, so I knew he still had his wit. And his job with the Church school system.

I had my breakdown a few weeks later, and in the hospital they told me to forget the past, get on top of my problems, and keep spiritually alive. Pat advice. But I don’t think I want to. I am comfortable being withdrawn, hating the world, because I’m most familiar with that emotion. And it’s a guarantee I won’t get hurt again.

Can I ever feel more than a child who has been violated? Can I ever feel more than a rutted calf who has become a rutted cow? Aunt Reba told Gladys this never would have happened if I had kept my mouth shut, “or better yet, kept her dress down and her pants up.”

Mother will not let this rest, and it is the only thing that comforts me. I think it is her way of rescuing me now, although it is too late. She keeps after Uncle Ed, trying to get him to come to Cynthia and me, apologize, and give us money for the therapy that is costing us so much. I tell her it’s pie in the sky, and we are dreaming, and Gladys says to consider him dead. It’s true, he won’t have anything to do with us. He just walks away.

Aunt Reba says to leave well enough alone. He already agreed with the stake president to make it up by working for the Church for a while, she says, and so he works on the stake newspaper, and that’s taking care of his repentance. And she jokes with some exasperation in her voice that maybe it would have been better if he’d thrown me downstairs after all, and giggles nervously.

I am Junior Primary chorister, and every other Sunday we sing, “I Am a Child of God.” I wave my arm and walk down the aisles and look at the children deeply, convincing each one that he or she is a child of a loving Father. At the same time, I am nurturing myself, trying to become convinced.

I love to read 3 Nephi, where the Savior asks, “Have you any afflicted among you? Bring them hither, and I will heal them.” And I prayerfully cry, “Here I am! Heal me! Please!” I am crawling, albeit slowly, toward Jesus’ hem, getting ready to touch it, and hoping to feel the newness rush into me.

This morning I went for a drive before dawn; and not too far above me I saw the moon, its old-man face turned into soft focus by the fog. As I watched its ethereal beauty, a soprano on a Christian radio broadcast began to sing, lovingly, “Jesus loves me, this I know, for the Bible tells me so . . .” All at once I felt the little girl in me reach up and begin to cry, and the song seemed to wrap itself around me.

The playhouse has made me hot and sleepy. Sweat is tickling my back and neck, and my body feels heavy. The spider has settled into her home for a nap, and she looks content. I rub my hands over the rough surface of the walls. Someday we’ll have to smooth these out. And maybe install some real glass windows that slide open. But for now, it is time for me to go inside.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue