Articles/Essays – Volume 12, No. 4

The Poetic Mystique | Marily McMeen Miller Brown, The Grandmother Tree, and Vernice Wineera Pere, Mahanga: Pacific Poems

Beyond the sentience and the craft, under the sound and shape and color of the poem, one seeks the mystique that synthesizes and sets forth a poet’s real reality. Marilyn McMeen Miller Brown’s book of insights into the lives of women in a rural pioneer culture where womanly intelligence, intuition and ingenuity often more than equaled the obstinacy or the courage of the men, presents the reader with an image of unusual sensibility and strength.

In a poem entitled “Rocking Chair Judge” she juxtaposes upon the raw brutality of frontier discipline the perhaps perverse maternal urge to protect and even love the faulted sinner in spite of his sin, small or great. Rocking, pleating her handkerchief as if she were pleating up time, the old one recalls saving a boy from a grandfather’s unreasoning punishment and, in a brave defiance, hiding and feeding an Indian in flight from certain death: Once out of the woods, an Indian limped, bloody, His blue lips trembling and begging for food./ Grandma gave him some bread from her larder./”They are comin’, I killed me my woman,” he told her.

Some of Mrs. Brown’s poems are almost pure narrative yet always lighted by the shine of compassion and love that foster and guard life for any child, old or young. Several poems imply the invaluable power of total identification with her subject so that she truly participates in the spirit of the woman she is experiencing. Such identification is in “Lesson” where, riding the horse her grandmother rode, the “druid shadow” becomes herself. In “Indian Playmate” she finds herself a mirror of that girl, in an interconnectedness that suggests profound spirituality. Rilke wrote, “When I create I am true.” Often, reading Mrs. Brown’s poems one is reminded of the lucent aura of understanding love which shines over her presences in a subtle resemblance not to any one poem but to Rilke.

For most of her readers, the appeal of this book will be in nostalgic episodes told by the grandmothers and shaped into free verse by the author with obvious delight. The humanity of these stories, the humor, the tenderness of touch make such stories as the hiding of a hen so Mama can’t slay it for Sunday dinner, the charming off of warts with a rag from Grandpa’s nightshirt, the ritual of Saturday night bath, the soap-making day, the each-canning day and other sunbeamed memories of “the olden days” nice to read. For me, the sense of kind and kindness is enough.

Poignant feeling for timeless primitive forces and for native traditions peculiar to her island home now “acculturated” by contact with mainland civilizations and their motorbikes, movies, and jukeboxes pervades Mahanga by Vernice Wineera Pere, a New Zealand poet of Maori, French and English ancestry. The best of her poems seem to speak a reverence for the irrecoverable lost heritage of time more rich and true. Two haiku crystallize this mood:

Premonition

A pale morning sky

moon of yellow tin-foil and

a black shag soaring.Laie

The deepening night

sleeping village bordered by

the rumbling ocean.

Some of the poems in this collection are more nearly essay, written, because of a good ear for verbal rhythms and melody, in the line lengths of free verse. These deal openly with personal attitudes and opinions, and are good moral reading, such as in “Waiting Room,” “Why Do We Smile,” “Transcendental Thought,” “Reflections,” “Split Personalities.”

The poem quality of those which deal with children and friends, teachers and pupils, is effective and affective, delicately achieved. But when the reader reads on more than one level, as in the homeland poems, power and mysticism combine to make the reading unforgettable. For example, in “Big Surf” the tides of ocean threatening the island become the tides of time and change, threatening to inundate her human world.

“—all our certainties

have come to grief

as we behold the thundering

turmoil of white water

smashing against the tenuous

off-shore reef

we dearly hope will hold.

“Acculturation”, though poetry ends and moral essay takes over two thirds of the way down the page, both tells of and creates images of the meeting of East and West. In “Pake Cake and Prayer” Charlie Goo’s store vibrantly illustrates and dramatizes the encounter with a carefully retrained lament for the coarsening of values by foreign interlopers.

the kids file in

hungry for pake cake and soda

crack seed, won ton chips,

and nacho cheese doritos.The juke box wails I love you

into the undistinguished morning.

“The Boy Named Pita,” “Hokulea” and many others are complex expressions of what seems most valuable and moving in this poeťs book. “Song from Kapiti” is a testament of genuine and admirable dedication. Hers is poetry we must feel to read, and having read it, we are grateful to know another woman who not only honors her people and explains herself but glorifies the images of humanness.

I am she learning to sing

the sweet sad songs of a people’s son

I am the lone bird

alive in a limbo of longing,

enduring the winter world,

surviving

on the slim promise

of a future summer.

In such poetry there is no need of startling techniques or unusual firecracker associations, as it would be superfluous to hang exotic costumes on a soul. IT is poetry that is needed, and reassuring.

The Grandmother Tree. By Marilyn Mc Meen Miller Brown. Provo, Utah: Art Publishers, 1978. xiii+56 pp., illus. $3.95.

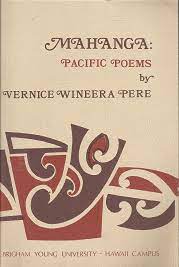

Mahanga: Pacific Poems. By Vernice Wineera Pere. Laie, Hawaii: Institute for Polynesian Studies (BYU-Hawaii), 1978. 39 pp., glossary, Paper $3.00. Cloth $9.00.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue