Articles/Essays – Volume 09, No. 2

The Politics of B.H. Roberts

Among the second generation of latter-day Saints, the Church had few more zealous or versatile advocates than B. H. Roberts. In his day he was the Church’s most prolific writer, its leading historian, one of its most popular and exciting speakers, a missionary, theologian, journalist, and widely admired champion of Mormonism before the world; and Roberts’ day was a long one—for nearly forty-five years he served as a general authority of the Church. Yet many of the same qualities which equipped him to be defender of the faith—his oratorical skill, polemical ability and total lack of aversion to controversy[1]—suited him as well for public life. Roberts was also a politician.

Not surprisingly, politics and religion in Roberts’ career were closely connected; by force both of circumstances and his own nature, he was required to pass judgment on his Church as a political influence, on its teachings as a guide to policy and on its authorities as temporal directors. Roberts’ reconciliation of church and state was not done in a corner but before a generation of fascinated Utah voters who came to regard him variously as apostate, embarrassment and political hero.

Roberts entered public affairs at a crucial period in Utah’s political life. After years of chafing under the rule of federal appointees, Mormons throughout the Territory ardently wished for statehood and attendant self-rule. Church leaders were trying to be accommodating; they had silenced the nation’s two major objections by renouncing polygamy in 1890 and approving, the following year, dissolution of the People’s Party, the vehicle of Church political influence.

Yet despite its formal abdication of authority in politics, the Church retained considerable sway over a people accustomed to looking to its religious leaders for guidance in all things—and Mormon leaders remained most solicitous for Utah’s temporal welfare. To avoid perpetuating the Mormon-Gentile rift that had characterized territorial politics, the Saints—nearly all of whom had been members of the People’s Party—were instructed to join with the national Democratic and Republican organizations. Yet, as Apostle Abraham Cannon wrote of the First Presidency, “They did not want [Church members] to go en masse to either party. If [the Saints] can divide about evenly between the parties, leaving an uncertain element to be converted to either side, it is thought the best results will follow.”[2] Members of the Presidency also were convinced that the interests of statehood would best be served by courting favor of the Grand Old Party; and when it appeared a majority of the Mormons would vote Democratic, the leading brethren decided to tip the balance a little. At a meeting of highest Church officials, as Joseph F. Smith reported, “it was plainly stated . . . that men in high authority who believed in Republican principles should go out among the people, but those in high authority who could not endorse the principles of Republicanism should remain silent.”[3] With the Presidency’s approval, Apostle John Henry Smith and others embarked on a campaign to promulgate Republicanism. When some of the other brethren expressed their disapproval, Joseph F. Smith, a counselor in the Presidency, explained: “We have received the strongest admonition from our Republican friends, that we must not allow this Territory to go strongly Democratic. We favored John Henry’s going on the stump so as to convince the people that a man could be a Republican and still be a Saint.”[4]

In 1892 Mormons held their first election along national party lines, and the campaign was an enthusiastic one. The politics of religion was much at issue. The two parties circulated rival pamphlets—both called “Nuggets of Truth”— arguing that Republicanism—or Democracy—was in the true political tradition of the Church. The campaign also featured the novelty of political encounters between leading churchmen, and among those most anxiously engaged was Roberts. The Semi-Weekly Herald, of which he was editor, published biting editorials condemning as “moonshine” the foolish opinion “that the population of the territory should be about evenly divided between the two great national parties in order that Utah might be favored of both parties, sought for and petted and at last secure her full rights.”[5] The paper also criticized attempts to insert religious argument into the campaign, branding some political utterances of John Henry and Joseph F. Smith as “an appeal to the prejudice and passion of the Mormon people” and “utterly unworthy of the gentlemen” who made them.[6]

As the election approached and the political climate followed a definite warming trend, the campaign activities of general authorities became distressing to the highest Church leadership. In early October, at a meeting of the First Presidency and the Twelve, it was decided that general authorities should no longer take the platform to make political speeches.[7] But some Church officials, convinced that the “damage” had already been done by the blatant partisanship of other authorities, would not be quieted.

The day following the Council’s decision against political stumping by Church leaders, eager Democrats by the thousands rallied and marched the streets of Provo before crowding into the new stake tabernacle for the state convention of their party. Among the highlights of the evening was an oration of “fiery eloquence,” enthusiastically described by the partisan Herald as “deserving a permanent place in current Democratic literature.” The speaker was the youngest of the First Council of the Seventy, thirty-five year old B. H. Roberts. “I shrink from the task you have assigned me,” he told the Convention,

perhaps for the reason that I do not account myself a politician and am little experienced in actual political work. But however limited my experience may be in practical politics, I have devoted some attention to the study of civil government, especially to the principles upon which our own government is bottomed; and after such reflection upon and analysis of the subject as my humble abilities will admit of, I arise from the self imposed task with the deepest conviction that I am a Democrat.[8]

The young general authority showed himself fully aware of the significance of his presence at the Convention:

There is another reason why I am pleased with this opportunity of speaking to you— I trust the fact of my doing so will be an evidence to you and all who may hear of it, that Democratic Mormons no less than their Republican brethren are free to affiliate with the political party of their choice, and give full and free expression to their honest convictions.

Anxious to dispel any notion of Church sanction for Republicanism, Roberts continued with the canvass until the election, which the Democratic candidate won by a wide margin.

After the election, Roberts found himself—along with two other general authorities who had continued to work for the Democratic campaign—subject to the discipline of the Church. Apostle Marriner W. Merrill describes a meeting of the Presidency and ten of the Twelve in which “the subject of Apostle Moses Thatcher, B. H. Roberts, and C. W. Penrose was discussed at length; they all went in direct opposition of the First Presidency policy in the last fall political campaign. . . . After a long discussion . . . it was agreed upon that the Brethren above named should not attend the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple until they made matters right.”[9] The three errant authorities thereafter apologized and made reconciliation; for a time at least, Roberts’ political activities were ended. The next year his efforts were devoted entirely to the work of the ministry.

Eventually, however, as Utah moved closer to statehood, Church authorities found it expedient to lift the ban on political participation. An 1894 act of Congress had authorized the election of delegates to a state constitutional convention, and the Church, desirous that its interests be represented there, decided to permit Mormon officials to become candidates. Roberts, as delegate from Davis County, was among four general authorities elected. But that he was no part of any Mormon lobby was soon evident.

Three weeks into the convention, Roberts drew the attention of people through out Utah by single-handedly turning what most had supposed to be a routine issue into what the Herald called “the greatest legislative fight in the history of the Territory.” The subject was woman’s suffrage. As women had previously voted in Utah elections—until denied the right by the Edmunds-Tucker law— and since neither party dared alienate the ladies by opposing female suffrage, the measure was expected to pass easily. Besides, the Church favored enfranchisement, as Roberts knew. As he later wrote, “Mormon Church leaders could see the practically doubling of the vote they could control in the event of their resorting to the exercise of ecclesiastical authority in politics. . . . In fact they had expressed a wish to see suffrage included in the Constitution.”[10]

But the Davis County delegate was adamant in opposition. He excused himself from any obligation to support his party’s position on the issue, saying political platforms were like “the shifting clouds of a summer day, and may be wafted where they may.”[11] Expediency required that woman’s suffrage not be included in the constitution, he argued, since it would endanger chances of ratification; Utah’s Gentile population would certainly object, and President Grover Cleveland was known to oppose the measure.

When another delegate challenged him to argue the merits—not just the politics—of the question, Roberts obliged with two lengthy orations on successive days; Utah’s womanhood attended to both with the keenest interest. Abundantly documenting his position both scripturally and from secular literature, Roberts demonstrated that woman’s role was domestic, not political. Anticipating his detractors, he assured his audience,

There is not a suffragist among you all that has a higher opinion of her and of her influence than I myself entertain. But let me say that the influence of woman as it operates upon me never came from the rostrum, it never came from the pulpit, with woman in it, it never came from the lecturer’s platform, with woman speaking; it came from the fireside, it comes from the blessed association with mothers, of sisters, of wives, of daughters, not as demo crats or republicans.[12]

He opposed female suffrage, he told the convention, because it was both unnecessary and unwholesome. Utah’s women were effectively represented already by husbands, sons, and brothers. And politics was a sordid business, no place for ladies. If suffrage were passed, he predicted, the sensibilities of the gentle women would cause them to shun the polls, while “the brazen, the element that is under control of the managers and runners of saloons, will be the ones to brave the ward politicians, wade through the smoke and cast their ballot.”[13] Eventually political involvement would prove debasing: “Let [suffrage] operate twenty years, let it operate fifty, a hundred years, we will have a womanhood from whom we will dispose to flee.”[14] Roberts was in earnest. (When his Davis County constituents threatened to demand resignation if he did not cease to oppose suffrage, he wired back, inviting them to do what they would. They reconsidered.)

Roberts’ widely acknowledged eloquence notwithstanding, Utah females were granted the vote by a large majority. But that was not the end of the matter for him. The extensive publicity given his arguments made Roberts’ name practically synonymous with anti-suffrage in the minds of many; in subsequent years he was often challenged to defend his “misogynous” views. Four years after the convention had adjourned, the Y.M.M.I.A. Young Women’s Journal could still ask Roberts to explain his feelings on the political status of women in Utah. He responded:

It was not contempt for women that led to my opposition to her enfranchisement, but my deep regard for her. It was not because I despised woman’s influence that I was opposed to equal suffrage, but because I feared that influence would be lessened. . . . It was not because I wanted to see man lord over woman. . . .[15]

The second issue of the convention to involve Roberts deeply concerned the attitude state government should adopt towards private business. Roberts saw corporate power as “that one great evil. . . which promises to overthrow the institutions of our country more than any other danger.”[16] Corporations, he warned, “have no bodies that you can kick, and they have no souls that you can tempt, and they are the most difficult things to contend with that ever confronted our civilization.”[17]

He spoke in favor of a state anti-monopoly law and proposed sections to restrict all corporations to “one general line of business.” He also urged that the state be prohibited from subsidizing private concerns, warning that otherwise legislators would be incessantly courted by men begging public aid to build private fortunes.[18] A question was quickly raised regarding Utah’s young sugar industry—in which the Church had invested heavily, and for which the territorial legislature had been persuaded to grant a bounty. Roberts insisted it should be no exception:

. . . I am not willing even that this enterprise, laudable as I grant you that it is, should be sustained and supported at the expense of the people of this State, because, however laudable this enterprise might be, it is very likely, sir, that other companies will form and other projects will be inaugurated which will not be so laudable. . . .[19]

The question of statewide prohibition inspired one of the liveliest debates of the convention, and it was the final issue to which Roberts addressed himself at length. Here, too, Mormon leaders had made their wishes known; while doubting the wisdom of inserting prohibition[20] into the Constitution for fear of alienating the Gentile population and thereby endangering ratification, President Woodruff did endorse a petition urging that a bill outlawing the sale and manufacture of spirits be put before the voters as a separate proposition.[21]

Roberts fully agreed with Church leaders as to the political unwisdom of writing prohibition into the Constitution; however unlike the Presidency, he could not muster much enthusiasm for any subsequent attempt to outlaw liquor. To Roberts, prohibition was a species of law governments had no business making and he opposed it—on moral grounds.

I believe in the liberty of the individual, and if you want to know how dear to me the liberty of the individual is, I want to tell you that . . . notwithstanding all the array of blood curdling incidents that may be related as growing out of the acts of men under the influence . . . so dear to me is the liberty of the individual that I would pay that price for it, and if I could, I would not destroy the liberty and agency of man.[22]

“May I ask the gentleman a question?” said another delegate. “How about the weaker ones—the wives and children of the unfortunate men?” “You may add that to the list also, if you will,” Roberts replied. ” I recognize, sir, that Omnipotence has the power to blot this thing out of existence and yet He withholds His Hand.”[23]

Even if passed, Roberts argued, a prohibition law would not succeed in its aims, and ineffective law was worse than none. “I am of the opinion that there are things worse than even intemperance in the use of intoxicating liquors, and one of those . . . is disrespect and disregard of law. . . . I say that it is easy to evade this class of law, and when you teach a community to disregard law, you create a greater evil even than the evil you attempt to crush by law.”[24] Utah didn’t have to give up its liquor that year.

Despite his well-known stand against prohibition at the convention, Roberts reversed his position in the next decade when a popular movement to make the state dry was throttled in the legislature by the powerful Republican political machine. While still acknowledging his original misgivings about enforced temperance, Roberts said in 1910,

I recognize the right of majorities to have their way and try such experiments in government as shall seem to them best. Therefore, since the liquor interest has stretched forth its hand to defeat the sovereign will of the people [he claimed a “deal” had been made with the Republicans]—I am for prohibition—for putting these corrupters of our government out of business.[25]

Roberts’ sudden zeal for outlawing liquor seems to have been attributable to his desire for a Republican defeat, rather than to any latent conviction he may have harbored as to prohibition’s virtues; after the Eighteenth Amendment im posed the Great Experiment on the entire nation, Roberts was advocating repeal. In 1928 he even went on radio in support of “wet” presidential candidate Alfred Smith. “What I mean to say,” he told his Utah listeners,

is that the national prohibition enactments, have not reduced the nation-wide evils of intemperance; and that the experiment has given birth to innumerable other evils that in the sum of them constitute a graver menace to our national life than the use of liquor under previous conditions prevailing in the United States.[26]

Despite the much-publicized activities of President Heber J. Grant, David O. McKay, and others of the apostles in favor of prohibition, so outspoken was Roberts for repeal that the Salt Lake Times could cite him to show that the Mormon Church as such took no position on the issue.[27]

In contrast to the claims of many Church leaders that prohibition was but the secular complement to the revealed injunction against the use of strong drink, Roberts wrote in 1933 of the “so-called moral reform,”

There is no identity between the L.D.S. Church’s Word of Wisdom and what is known as Prohibition. The former rests upon persuasion, upon teaching, upon education and that without compulsion or constraint. The other, State Prohibition, should be enforced with fines, imprisonment and often it has proven to be at the cost of life in pursuance of such enforcement of law and if the Church undertakes to enforce it by penalties or should turn it over to be enforced by the state through pains and penalties, then the Church would be changing and relegating its discipline to enforcement by the state and thus grossly depart from the high moral and spiritual grounds upon which its supplanted Word of Wisdom has been placed by the Almighty.[28]

The independence of the positions taken by Roberts at the convention vis-a-vis the Mormon Church did not go unnoticed or unappreciated. As a prominent Utah Democrat later recalled, Gentiles and young Mormons especially “admired . . . the man’s courage and ability; and they thought then . . . that B. H. Roberts was the Moses who was going to lead us out of our political troubles. . . . They believed that with the stand he was taking, and the independence of the man, and his ability to lead, it would result in his leading the people away from church domination.”[29]

In the fall of 1895 the Democratic party made the young Seventy their candidate to become the first congressman from the new state. (They chose another prominent Church leader, Apostle Moses Thatcher, to run for the Senate.) Soon Roberts was vigorously stumping the Territory, delivering well-documented speeches on the political questions of the day—the tariff, silver, the issue of bonds, and “hard times.” But before election day, the issues of the campaign were to change.

During a session of the October General Conference of the Church, Joseph F. Smith of the First Presidency gave a talk in which he censured two high Church officials for their disregard of Church authority in entering the political arena without first obtaining the permission of the Presidency. Although no names were mentioned, the identity of the pair was never in doubt; soon political opponents were gleefully suggesting that Roberts and Thatcher, in running for office, were derelict in their Church callings and that their election would be contrary to the will of the Brethren.

Coming as it did just before the November elections, and from an “intense Republican,” as Roberts described President Smith, the statement was strongly resented by Democrats as an “ecclesiastical interference.” The Herald described the controversy that ensued:

Never in ten years has there been so much deep excitement as there was in political circles yesterday. Men were wondering what the church authorities would do, what the Democrats would do, and what the Republicans would do. Everywhere speculation was rife. . . . Mormons joined with Gentiles in saying that the time has come when it should be forever settled as to what position the Mormon church officials shall occupy in our politics.[30]

In his private journal, President Woodruff described the situation more succinctly: “All Hell is stirred up with the whole Democratic Party against the Church. A Terrible War. . . .”[31]

Roberts soon made clear his position in the controversy. One week after Conference a long “interview” written by himself came out on the front pages of two Salt Lake dailies.[32] Describing the recent history of his political involvement, Roberts recounted how, before the Constitutional Convention, he went to one of the First Presidency for his approval. “I said to him that my acceptance of the nomination for delegate . . . would involve me again in active politics. . . . The gentleman in question [later identified by Roberts as Smith] said that would be all right, and I again entered the political arena. . . .”[33] Since accepting his party’s nomination, Roberts said, he had met privately with the First Presidency to discuss various matters, and was in no way reproved for his political activity. Thus, while acknowledging both the right of Church authorities to restrict the political activities of Church officials, and the duty of those officials to either submit to such regulation or else resign their offices, Roberts insisted, “In this case I consider that I have violated no church rule, and if arraigned before my quorum or any church tribunal on such a charge I should answer NOT GUILTY. . . .”[34]

If the Church permits its general authorities to enter politics at all, Roberts continued, then “those men ought to be absolutely free to follow their own discretion as to what their politics shall be. . . . I do not believe that Democratic church officials ought to be expected to go to Republican superior church officials for counsel in political affairs,” as that would give the Church too much influence in public affairs. For Roberts there was “no middle ground between absolute and complete retirement on the part of high Mormon Church officials from politics, or else perfect freedom of conduct in respect to politics. . . .”

His own intentions, he declared, were to resign if so requested by his party—otherwise to continue in the race in order to “crush this church influence—not used by the First Presidency of the Mormon Church but by the Republicans who have taken advantage of this unfortunate circumstance. . . .”

I do not know what the results will be to my religious standing, but in this supreme moment I am not counting costs. I shall leave all that to the divine spirit of justice which I believe to be in the authorities of the church of Christ. I shall trust that spirit as I ever have done, and I say to the Democratic party that while my position in the church of Christ is dearer to me than life itself, yet I am ready to risk my all in this cause.[35]

In short order the Democratic party reconvened its state convention, voted to renominate all its original candidates—and then lost every contested office^ except a few seats in the legislature. Roberts was defeated by 897 votes. (In the same election the Constitution was accepted by the voters, and on January 4, 1896, a proclamation of Utah statehood was signed by President Grover Cleveland, a Democrat.)

The First Presidency were not pleased with the conduct of the campaign. John M. Whitaker, at the time Secretary to the First Council of Seventy, describes a meeting with the Church leaders shortly after the election:

. . . I was called into the office of the First Presidency and in the back office President George Q. Cannon called my attention to the “severe and caustic statements of President Roberts against the unwarranted interference of the First Presidency and some of the Twelve in political matters and whispering Campaign and had manifested such a bitter spirit that we have had the matter under discussion for some time. We do not wish in the least to do anything to give color to the thought that we sustain his political talks and his actions in the last campaign; or that we in the least countenance his words and actions and his course; at the same time we do not wish to do anything that would hurt him in the least; but the course he has taken if followed by the members of the First Council would lead to disunion and disruption, and we cannot fellowship him until he has made them right.” At this point President Wilford Woodruff came in and told me practically the same thing and further that they would handle Brother Roberts now, and some other men of the authorities also, if it were not for statehood . . .”[36]

In February 1896 a meeting of the general authorities was held in the temple to consider the Roberts case. (Moses Thatcher was in ill health and unable to attend.) Brigham Young, Jr., of the Council of the Twelve described the session in his journal: “I was appointed to open the case which I did reading many extracts from an interview Br R had with a Herald reporter. He denied nothing & took back nothing. Made some explanations on some unimportant points but repeated his obnoxious expressions as the sentiments of his heart now.”[37] Apostle Merrill describes the same meeting:

Brother Roberts made a statement justifying himself in his course, after which all present condemned Brother Roberts’ conduct and asked him after 8 hours’ meeting in laboring with him to make reconciliation with his Brethren and the Church, which he refused to do. Then meeting adjourned . . . to give him time to consider and report further at some future meeting. . . . All of the Brethren present felt bad, even to tears with many, for the stubborn disposition Brother Roberts manifested.[38]

In March, a second meeting was called. The situation was reviewed and again discussed by the general authorities. As Young recorded it, when asked to state his feelings,

Bro R. said he felt just as he did at last meeting. Bro Golden Kimball asked Pres. what was demanded of Bro Roberts. I asked privilege of answer—only I said a broken heart & contrite spirit, Bro. R. could not give this; I fear for him. Adjourned for three weeks. Bro R. was dropped from his position until then; if he repents, all well, otherwise he will loose his standing among the Seventies.[39]

At the direction of the First Presidency, a document known as the “Political Manifesto” was prepared, setting forth as the rule of the Church that

before accepting any position, political or otherwise, which would interfere with the proper and complete discharge of his ecclesiastical duties . . . every leading official of the Church should apply to the proper authorities and learn from them whether he can, consistently with the obligations already entered into with the church . . . take upon himself the added duties . . . of the new position. To maintain proper discipline and order in the church we deem this absolutely necessary. . . .[40]

Before being presented to the Church at General Conference, the document was to be signed by each of the general authorities, thus “giving [Roberts and Thatcher] an opportunity also to sign it, and thus show whether they were in harmony with their brethren.”[41] This, according to the Journal History of the Church, “was considered necessary at once, in view of the precarious condition of Thatcher’s health, and the importance of having the question involved settled for all time to come.”[42]

But Roberts was of no disposition to sign. His autobiography recalls his suspicions:

. . . it can not wholly be disregarded that it is an instrument to be used with exceeding great care, because it could be so easy either by the giving or withholding of consent to indicate the wishes of the administration of the Church as to the desirability or undesirability of men in opposite parties running for office. Especially in a community where is much anxious willingness to comply with the slightest wishes of ecclesiastical authorities. . . . That there had been good ground for suspecting ecclesiastical intention to control the political affairs of the state can scarcely be denied. . . .[43]

A committee composed of Heber J. Grant and Francis M. Lyman was assigned to persuade the recalcitrant Seventy. After days of trying to convince Roberts, the two received the following letter.

I submit to the authority of God in the brethren. While I cannot for the life of me think of anything in which I have not acted in all good conscience, and with an honest heart, since they think I am in the wrong, I will bow to them, and place myself in their hands as the servants of God. This day thirty-nine years ago I first saw the light, and now after this trouble, I feel lighter. I thank you for your goodness to me.[44]

To the disappointment of some and the surprise of many, when the Manifesto was read at April Conference, Roberts’ name was signed to it.

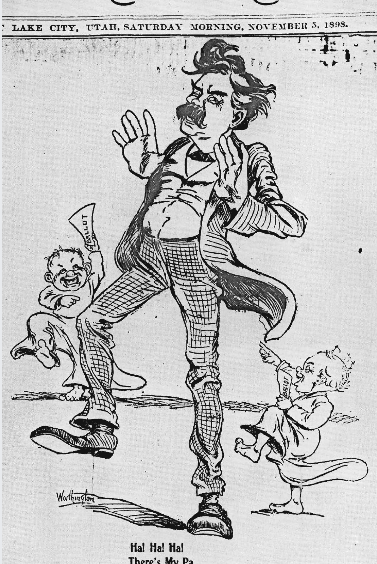

He did not, however, abandon his ambitions to someday sit in Congress. In 1898, after returning to Utah from a period of service in the mission field, Roberts got the permission of President Lorenzo Snow to seek public office, and at his party’s convention in the fall, he was chosen to run again for Utah’s seat in the House of Representatives. Roberts was a polygamist, but his marital status had not been a major issue in his earlier campaign, and he was confident the matter would not be politically disabling. But events did not justify his hopes; times were not propitious for a candidate with three wives.

Throughout the campaign Roberts was pilloried by the Salt Lake Tribune and various sectarian groups on a number of counts, especially for his polygamy. Meanwhile, the Church did little to defend him; the Church-owned Deseret News avoided discussion of specific campaign issues, and President George Q. Cannon’s timely opinion (announced a few days before the election)—that “any man who cohabits with his plural wives violates the law”[45]—was no help.

Roberts nevertheless managed to win the election, and he arrived in the nation’s capital the following year to be sworn in to office. But his difficulties were not ended; he found in Washington strong sentiment against seating a polygamist. Objections to the admission of Roberts into the House prompted several weeks of intermittent discussion. Meanwhile the forty-two year old Mormon drew the attention of the national press, as many papers devoted entire pages to the question of Roberts, the Congress, and the wives. Finally, by a vote of 268 to 50, the Fifty-Sixth Congress ruled that the Representative-elect from Utah should not have place in the House.

Roberts’ failure to retain his Congressional seat was a damaging blow to the prestige of the Democratic party in Utah, and he felt sure that it had effectively ended his career in politics. Yet he continued to be an influential figure among Utah Democrats. Years later the Intermountain Republican could still call him “the biggest of his party in Utah.” Roberts enjoyed a great reputation as an orator, and his political utterances continued to command much attention—particularly when the subject was Church influence in politics; and for the next decade it often was.

In 1903 Utah’s state legislature elected Senator Reed Smoot, Republican and member of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles. The spectacle of an apostle—one sustained by the Church as prophet, seer, and revelator—taking part in the heated wars of partisan politics—created something of a dilemma in the minds of many Mormon Democrats who were anxious to be good Saints but who disagreed with the Senator’s politics. To such the remarks of President Joseph F. Smith at the 1906 General Conference must have been less than reassuring; as Whitaker records,

he made it clear that . . . when the people vote to sustain anyone in a political position, that person is at liberty to accept if he or she so chooses and Reed Smoot had the confidence and support of the General Authorities of the church in his present position as Senator from Utah.[46]

By 1908 when Smoot first came up for re-election, several in the leading councils of the Church openly questioned the propriety of a man’s serving as both Apostle and Senator. But President Smith, convinced that the Lord willed Smoot’s continued service in Washington, never revealed any such misgivings. To the contrary, in a fast meeting (attended by Roberts), the Prophet condemned “the cowardice of some of our brethren who felt to regret that we had an apostle in the Senate. He characterized such sentiment in the strongest language he or any other man could use,” and expressed his desire to see Smoot re-elected.[47] Two of the Senator’s closest associates wrote to him that Smith had instructed the editor of the Era to support Republicanism[48] and had promised them, “I will take my counsellors and the twelve one by one and tell them what I want done, then I will see Bishop Nibley and some of the others.”[49] Criticism of Smoot by the general authorities thereafter subsided. Roberts was the conspicuous exception.

A few months after President Smith’s fast meeting remarks, Roberts composed a letter detailing his opposition to Smoot’s re-election. It immediately obtained wide circulation in Utah political circles and eventually appeared in the Salt Lake papers. The letter protested patronage of Smoot by the Church, and urged that the

candidacy of Reed Smoot and all other political issues should be regarded in the light of absolute certainty that Utah is destined to become a non-Mormon state. . . . It is for those who are directing the policy of our church to consider whether they will have it anti-Mormon as well. . . .[50]

In Utah, Roberts wrote, there were 500 persons as qualified as Smoot to represent the state—and without perpetuating the “old antagonisms.” True, Smoot was an apostle—that was undeniable; “. . . as I must needs believe that this gentleman was called to his apostolate by inspiration, it removed him beyond my criticism in that capacity.” But Roberts could not resist: “My observation leads me to the conclusion that God accomplishes his purposes at times as well through weak instrumentalities as through strong ones. . . .”[51]

Shortly before the 1908 election Roberts delivered a second well-publicized statement of personal policy regarding Smoot and the Republicans. Before a large crowd in the Sixteenth Ward amusement hall, he gave a two hour speech, reported in detail under the headline “Roberts, Stalwart Saint, Trains His Guns on Smoot.”[52] The speech contained harsh remarks on “gumshoers,” petty Church officials, self appointed messengers of the Brethren, who, in the words of a Tribune editorial, went about in political campaigns “brothering and sistering” Church members, enlightening them as to the supposed will of the authorities. Roberts accused the Republican organization of scheming to subvert his influence by such a “whisper campaign”—

The men who go gumshoeing in this political campaign represent me as untrue to my people and my church, and a traitor to them, and that I am on the highway to apostasy and not to be trusted. It is about time that some manhood should stir in me and I should urge those whom I can influence to stand against such damnable infamy as this.[53]

Roberts and the Democrats were anxious that Smoot not get the votes of the undiscerning merely on the strength of his prestige as an apostle. Roberts assured his audience, “Whatever honors a man may hold do not grant him a priori supremacy as a governor.” Issues—not extraneous credentials—should decide the election.

Men come, men go; men die, men change, but the truth remains. Principle remains. The only admonition that my church gives to me, and the only law by which I will be governed in this particular, is this: Son, sit down, take counsel with thine own soul; investigate these doctrines, think them over, make up your mind as to what is the truth . . . make up your own mind, for you by these methods are in tutelage for higher things.[54]

Despite all Roberts’ efforts to the contrary, 1908 was a Republican year in Utah, and Reed Smoot was returned to the Senate for another term. Things did not look bright for Utah Democrats after that. Smoot was successful in defeating a popular movement—endorsed by Roberts and his party—to bring about statewide prohibition; when owners of the Democratic Herald—no longer optimistic about the future of their party in Utah—sold the paper, Reed Smoot and the Church purchased controlling interest and merged with another paper to form the Herald Republican.[55] At the same time, President Smith showed no signs of flagging in his support for the Republican senator. For Roberts the situation was discouraging. Writing of political conditions, he complained to a friend,

The betterment forces move so slow in Utah. . . . Meantime, here and there, are dropping from the rank of our Church some of the brightest intellects and best souls that we have. Not openly and defiantly but just quietly dropping out—losing interest, and patience and faith. The situation to me is only tolerable, because I have an abiding faith in the higher and deeper principles of Philosophic Mormonism with which I am interesting myself and which the errors of administration and sometimes the stupid inefficiency of Church officialdom cannot affect.[56]

For years the intrusion of the Church into politics remained a sore spot with Roberts. When an editorial appeared in the Church-owned Deseret News minimizing the extent of ecclesiastical influence in political affairs, he shot back an angry letter, calling it “the most palpable thing in this world that such influence is used,” and offering for publication a review of such interferences in Utah politics which he had prepared.[57] The News wasn’t interested, but the issue did bring about a lively exchange of letters.

Editor J. M. Sjodahl responded to Roberts’ assault by blandly asserting that Church officials no less than other citizens have political rights and suggesting that it was inappropriate for Roberts, of all people, to make such complaints. (Republicans commonly charged Roberts with hypocrisy; for all his supposed grievances against “Church influence,” had not he run for office while a general authority, and had not he campaigned for Moses Thatcher, who was at the time an apostle?)

Roberts claimed a distinction was in order. While acknowledging “a certain influence” exercised by Church leaders who entered politics, it was to be considered personal—not Church—influence “so long as the individual confines him self to usual political methods—speaking from the political platform exclusively, etc.”[58] The troubles in Utah, Roberts insisted, had arisen “through Church officials not confining themselves ‘to usual political methods,’ ” but using “ecclesiastical authority in Political matters” such that “the individual upon whom it is exercised may not resent or resist without the sense of feeling that he is resisting an authority which to him, represents God.”[59]

Roberts again volunteered a list of interferences in recent elections; it included remarks by President Smith to the effect that the Lord willed the re-election of Utah’s congressional delegation. And Roberts volunteered his appraisal: “I say it is abominable! Disgraceful alike to the Church and to those who participate in it. It is an act of bad faith. Damnable!”[60]

Sjodahl countered, justifying Church leaders in speaking to any subject— politics included—if they felt so inspired. But Roberts, who no doubt thought the political inspiration of any Smoot loyalist to be highly suspect at best, prudently based his objections on other grounds.

. . . From this violation both of usual political methods and the declared principles of the Church, comes our political woes, anger, and bitterness—and they will continue and be intensified until a halt in such methods shall be called, for they are intolerable in American politics and will have to be abandoned.[61]

“I appreciate your learning, your character and what I believe to be your good intentions to aid the work of God,” wrote Roberts at the conclusion of a letter to Sjodahl, “but unhappily we are fallen upon unpropitious times, where men of best intentions may easily misunderstand each other. Most earnestly do I pray that God will inspire the men charged with the administration of our affairs to change conditions.”[62]

In public as well, Roberts continued the protest. Before the 1910 election, he gave a speech in the Salt Lake Theatre, repeating the old refrain: “I hope yet to see the Mormon church free from the dishonor of unholy alliances with political tricksters . . . until the church shall make it her sole business to make men, and leave men to make the state. . . . “[63]—the perennial complaint. And yet within the statement is contained the irony of Roberts’ long political crusade: he was a prime example of men the Church made. And while he could seethe when the authorities seemed to lend the sanction of Church office to their political predelictions, Roberts himself habitually perceived affairs in terms of the gospel and expressed himself in the idiom of the Church. For one who believed the principles of the Democratic party to be “self existent,” “eternal as God is, and .. . no more to be created by man than gravitation,”[64] the temptation to offer the Saints political counsel was irresistible at times.

The great League of Nations controversy was one of those times. Almost from the beginning Roberts perceived great meaning in the war in Europe. In his October 1914 General Conference address he declared his belief that from the conflict would emerge “higher planes of civilization.”[65] From the same pulpit a year later he predicted the formation of a league of nations that would “establish an empire of humanity” by suppressing feelings of nationality.[66] And in 1917, after America had entered the War, he assured the Saints, “If there ever was a holy war in this world, you may account the war that the United States is waging against the Imperial Government of Germany as the most righteous and holy of wars.”[67]

To a Sunday crowd in the Tabernacle, Elder Roberts expounded at greater length on the religious meaning of the Great War. “Amid plot and counterplot, glory and defeat, you may observe if you study well the course of history in this world, you may see being builded up as by unseen hands a mighty progress in the accomplishment of God’s purposes in the advancement of higher phases of civilization. . . . That is what I regard as the triumph of righteousness in the war. …”[68] He added,

I believe, in my soul, that the kingdom of humanity is coming; that the long-predicted world peace is at hand. .. . As sacrifices bear some proportion to the blessings that follow . . . behold then in the presence of all the sacrifices that the world has made during these last three years of dreadful war—can the heavens themselves contain the blessings that God has in store for the world… ?[69]

By 1918 the vehicle of God’s blessing to a troubled mankind had become clearly identifiable to Roberts—the League of Nations proposed by Woodrow Wilson as part of the peace settlement. When, in the next year, citizens throughout the country were debating the advisability of American entrance into the League,[70] Roberts commenced an evangelistic campaign to convince Utahans of their duty in the matter. God’s purposes would succeed—of that he was sure—but only after overcoming the determined opposition of such men as Reed Smoot and Major J. Reuben Clark, Jr., who traveled about speaking against U. S. entry.

When the Mountain Congress for a League of Nations held its convention at the Tabernacle in February, 1919, Roberts delivered a major address (which he had published a month later in the Era).[71] It was probably his most impassioned effort in the League’s behalf. Citing Isaiah’s prophecy of a peaceful time of plow shares and pruning hooks, Roberts asked his audience, “Are these dreams of a golden age of peace to be realized, and is such a thing possible? I answer for myself, yes! Most emphatically, yes!” for “God has decreed that it shall come to pass, and who can disannul his word or stay his hand? And secondly . .. because it has become recognized as a world’s need by enlightened minds in all nations. . . .” And moreover, he added,

is the time now, and is it to be the high privilege of the men of this generation to inaugurate the means which shall establish and maintain through its infancy this universal peace age?— I answer, again for myself, yes, most emphatically, yes! God’s hour has struck! Man’s opportunity has come. The next step in the world’s progress is to organize a League of Nations. . . .

But to Elder Roberts’ great dismay, the League was not so highly regarded in Washington. By March, 1920, the plan had met its death in the Senate. Still, the dream died hard with Roberts. As late as 1928 he would proclaim to a “Peace Sunday” gathering in the Tabernacle,

I regard the establishment of this League as the finest effort made to realize the song of the angels at the birth of the “Prince of Peace.” . . . if my voice could reach the whole people of the United States, I would say to them what I say to you, and that is: Reverse the policy into which we have fallen in the matter of withholding from membership in the League of Nations . . . it was a mistake and time is proving it to be so.[72]

The League was not the only political topic on which Elder Roberts spoke from the pulpit. In 1921 he made the Washington Conference on disarmament the subject of his General Conference address. He admonished the Saints,

. . . while I do not know whether [the disarmament talks] will be successful or not, I think I do know that it is the duty of the membership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter day Saints to put forth every effort within their power to further the probability of the limitation of armaments among the nations of the earth. . . .

. . . since this international conference proposes to limit the armaments of both land and sea forces, I for one hail it as an indication that the Spirit of the Lord is working in the hearts of the people and the leading statesmen of the world to bring to pass peace among the nations, so I want the privilege, for one, of standing in the midst of my fellows and at least raising my voice in good cheer toward the achievement of that noble end. . . .[73]

Elsewhere he raised his voice for other causes, urging Church members to protest plans to increase American naval strength, and to support a movement to outlaw the use of airplanes, submarines, and women in warfare.[74]

Roberts must have raised some eyebrows, too, such as when, as the Church’s representative to the “World Fellowship of Faiths” at Chicago in 1933, he declared, “There is a necessity and a demand for planned and controlled industry by government, or government agencies;”[75] or when he said, speaking of massive government expenditures,

Let us hope that as an emergency policy it will meet with such success as will place the people in a position to construct a new economic policy, for a new age, to take the place of the capitalistic system and its spirit, wherein shall exist more equality and more justice than in the age now passing; a policy wherein there will be a more consistent division of the profits of the conjoint products of capital and labor than heretofore; where the wealth produced by that conjoint effort shall not forever flow into the possession of the “one,” while the “ninety and nine” have but empty hands ![76]

Other Church leaders must have resented what they considered to be Roberts’ unwarranted politicizing from the pulpit, his attempts to make religious issues of political options. Several of the general authorities were known to oppose the League, and many were less than delighted with the economic policies of the Roosevelt administration. Did not Roberts’ pronouncements on these and other subjects contradict the burden of his own crusade—to remove ecclesiastical influence from politics?

Roberts probably did not think so. He explained at the 1912 General Conference of the Church his belief that there exist for Latter-day Saints two separate realms of thought.[77] One comprised the “essentials”—the realm of theology and ethics. (“. . . there is no ground for serious division among us in respect of what is truth, and justice, and righteousness, and morality in all things, and in all relations.”) The other, comprising everything else, was the realm of “non-essentials”— “where one man’s judgment may be as good as another’s.” That Elder Roberts located religion in the first realm and politics in the second seems clear; that he found the boundary between the two clearly distinguishable does not.[78]

[1] In considering Roberts’ political career, it is important to remember that his recalcitrance against Church authorities was not confined to matters of politics. Docility was never his hall mark, and he felt little compulsion to make a show of unity with the Brethren when in fact he felt at odds. His correspondence reveals other incidents of dissent—over policies of the Church, points of doctrine, and the writing of Church history.

[2] MS Journal of Abraham H. Cannon, June io, 1891, Brigham Young University Library, Special Collections.

[3] Salt Lake Tribune, May 10,1896. Spoken by Joseph F. Smith to the Cache Stake High Council in reference to a meeting held in 7.891. In general, spelling, grammatical and punctuation errors have been silently corrected in citations from MSS and early publications.

[4] A. H. Cannon Journal, op. cit., July 9,1891.

[5] “False Lights,” editorial in The Issues of the Times, a pamphlet composed of materials appearing originally in the Salt Lake Semi-Weekly Herald, n.d.

[6] “Some Bits of History,” editorial reprinted in The Issues of the Times, ibid.

[7] Journal of Wilford Woodruff, October 4, 1892, cited in Brigham Henry Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (6 vol., Salt Lake: Deseret News Press, 1930), IV:33i, n. 9.

[8] Salt Lake Herald, October 9,1892.

[9] Journal of Marriner Wood Merrill, March 23, 1893, cited in Melvin Clarence Merrill, Utah Pioneer and Apostle: Marriner Wood Merrill and his Family, n.p., 1937, p. 162.

[10] Brigham Henry Roberts, unpublished autobiography, 1933, photocopy of typed MS with Roberts’ penciled corrections in Brigham Young University Library, Special Collections, pp. 379-380.

[11] Utah, Official Report of the Proceedings and Debates of the Convention Assembled at Salt Lake City on the Fourth Day of March, i8g^, to Adopt a Constitution for the State of Utah (2 vol., Salt Lake: Star Printing Co., 1898), 1:427.

[12] Ibid., 1:424.

[13] Ibid., 1:472.

[14] Ibid., 1:588.

[15] Brigham Henry Roberts, “The Political Status of Women in Utah,” Young Women’s Journal (March, 1899), 104.

[16] Convention, op. cit., 11:1469.

[17] Ibid., 11:1553.

[18] Ibid., L899.

[19] Ibid., 1:924.

[20] Roberts, Autobiography, op. cit., p. 380.

[21] Deseret News, January 5,1895.

[22] Convention, op. cit., 11:1459.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid., 11:1458.

[25] Deseret News, November 1,1910.

[26] Talk reported briefly in Salt Lake Tribune, October 16, 1928. Full text in B. H. Roberts Papers, Church Historical Department, Salt Lake. A hand-written note on the front page, “A very unwise speech by a very unwise man,” is signed “J. F. S.”

[27] Salt Lake Times, June 6,1930, cited in George H. Skyles, “A Study of the Forces and Events Leading to the Repeal of Prohibition and the Adoption of a Liquor Control System in Utah” (unpublished Masters thesis, Brigham Young University, 1962), pp. 21-2.

[28] Roberts, Autobiography, op. cit., pp. 391-391V2.

[29] Testimony of Orlando W. Powers, in Proceedings before the Committee on Privileges and Elections of the United States Senate in the Matter of The Protests Against the Right of Hon. Reed Smoot, a Senator from the State of Utah, to Hold his Seat (4 vol., Washington: Government Printing office, 1904), 1:927-8.

[30] Salt Lake Herald, October 13,1895.

[31] Journal of Wilford Woodruff, October 14, 1895. Microfilm copy of original MS in Church Historical Department, Salt Lake.

[32] “Roberts’ Strong Position,” Salt Lake Herald, October 14, 1895. Also Tribune of the same date.

[33] Herald, ibid.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Journal of John M. Whitaker, December %, 1895. Copy of Typescript in Brigham Young University Library, Special Collections.

[37] Journal of Brigham Young, Jr., February 13, 1896. Microfilm of original MS at Church Historical Department, Salt Lake.

[38] Marriner W. Merrill Journal, February 13, 1896, cited in Merrill, op. cit., p. 197.

[39] Young Journal, op. cit., March 5,1896.

[40] The document is reprinted in James R. Clark, ed., Messages of the First Presidency (5 vol., Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1966), 111:271 ff.

[41] Journal History of the Church, March 12, 1896. This is a daily compilation of documents, newspapers, etc., pertaining to the history of the L.D.S. Church.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Roberts, Autobiography, op. cit., p. 401.

[44] Reproduced in Journal History, March 13, 1896. At a stake conference two months later Apostle Heber J. Grant gave an account of the circumstances leading to Roberts’ signing of the Manifesto. As reported in the Tribune,

Day after day and night after night they [Grant and Lyman] went to him and wept and prayed, and he [Roberts] wept and prayed, but insisted that he had done no wrong. This continued for nine weeks, at the end of which time he yielded. One morning he appeared before the authorities and told them he was ready to acknowledge his wrong, and would sign any paper they might ask him to sign, or do anything they might tell him to do. His dead relatives, he said, those who had died outside the church, had appeared to him in a vision and had asked him to bow to the will of the authorities, and retain his standing in the church, in order to do temple work for their salvation.

This was the story of B. H. Roberts’s submission as told by Heber J. Grant. [Journal History, May 10, 1896.]

[45] Salt Lake Tribune, November 7, 1898. Cited in R. Davis Bitton, “The B. H. Roberts Case of 1898-1900/’ Utah Historical Quarterly, 25 (Jan., 1957), 27ft. Bitton’s article contains a good discussion of the issues involved in the decision to bar Roberts from the House.

[46] Whitaker Journal, op. cit., October 8,1906.

[47] Letter from Susan Young Gates to Reed Smoot, January 5, 1908. Cited in Milton R. Merrill, “Reed Smoot, Apostle in Politics,” (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University, 1951) p. 129.

[48] Letter from James Clove to Reed Smoot, January 16, 1908. Cited in Merrill, ibid., p. 146.

[49] Letter from E. H. Callister to Reed Smoot, January 10, 1908. Cited in Merrill, ibid., p. 146.

[50] Letter to Richard R. Lyman, March 30, 1908. Copy in Journal History of that date. First published in the Intermountain Republican, May 7,1908.

[51] Ibid.

[52] Salt Lake Tribune, October 30,1908.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Report of speech in Salt Lake Herald, October 31,1908.

[55] MS Journal of Reed Smoot, September 2, 1909. Brigham Young University Library, Special Collections.

[56] Letter to Isaac Russell, September 9, 1910, in B. H. Roberts Papers, Church Historical Department, Salt Lake City.

[57] Letter to Editor of Deseret News, November 21, 1910, in B. H. Roberts Papers, ibid.

[58] Letter to J. M. Sjodahl, November 23, 1910, in B. H. Roberts Papers, ibid.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Letter to J. M. Sjodahl, December 8,1910, in B. H. Roberts Papers, ibid.

[62] Op. cit.

[63] Journal History, November 5,1910.

[64] Notes for “Jackson Day Speech,” n.d., in B. H. Roberts Papers, op. cit.

[65] Conference Report, October 1914, p. 167.

[66] Conference Report, October 1915, p. 140.

[67] Conference Report, October 1917, p. 100.

[68] Deseret News, September 5,1917.

[69] Ibid.

[70] The controversy as it affected the Mormons is the subject of an article by James B. Allen, “Personal Faith and Public Policy: Some Timely Observations on the League of Nations Controversy in Utah,” BYU Studies, XIV (Auturn, 1973) p. 77 ff.

[71] Improvement Era, XXII No. 6, April 1919, p. 474 ff.

[72] Journal History, January 8,1928.

[73] Conference Report, October 1921, p. 194 ff.

[74] Deseret News, January 14,1928.

[75] “Economics of the New Age,” published in Brigham Henry Roberts, Discourses of B. H. Roberts, (Salt Lake: Deseret Book Co., 1948), p. 117.

[76] Ibid., pp. 119-120.

[77] Conference Report, October, 1912, p. 30 ff.

[78] President of the Church Joseph F. Smith responded to Roberts’ analysis in some extemporaneous remarks at the conclusion of the session in which the Seventy spoke:

If my brethren and sisters will indulge me just a moment I have this to say with reference to the discourses we have heard this morning: I believe in all that has been said, and I also believe a little farther than that which has been said….

I think that in the realms of liberty, and the exercise of human judgment, all men should exercise extreme caution, that they do not change or abolish those things which God has willed and has inspired to be done. . . . God in His boundless wisdom and gracious mercy has provided means, and has shown the way to the children of men whereby, even in the realms of freedom and the exercise of their own judgment, they may individually go unto God in faith and prayer, and find out what should guide and direct their human judgment and wisdom; and I do not want the Latter-day Saints to forget that this is their privilege. I would rather that they should seek God for a counselor and guide, than to follow the wild harangues of political leaders, or leaders of any other cult. I felt like I ought to say that much; and I know that I am right. (Conference Report, October, 1912, p. 41.)

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue