Articles/Essays – Volume 55, No. 2

The Promise and Limitations of Working-Class Male Protagonists

The ten stories that comprise Losing a Bit of Eden sustain Levi Peterson’s position as one of the most adept scribes of the twentieth-century American West. Each story is well grounded in a particular time and against a specific landscape, and somehow all feels gently connected.

There is no doubt that Peterson is a master of language. This volume is brimming with striking turns of phrase that linger long after one closes its pages. Several times I came across a line or a moment that made me stop and breathe: This is the good stuff. This is what I’m here for. One such instance is found in the story “Jesus Enough”; it’s the moment for which the story is named. When protagonist Darby’s mother dies, he has the following conversation with his stepfather:

“Dying, I mean. Just suddenly not existing anymore.”

Darby nodded.

“It could make you wish Jesus was real.”

“Yes, sir, it could. It does.”

Folks you live with believe he’s real, I suspect.”

“They do.”

Jack loosened his tie. “Just having her was Jesus enough for me.”

That exchange, simple and unassuming and so very real, hit me hard. There are several other moments like it peppered throughout. “Jesus Enough” is broken up into yearly episodes in Darby’s life in turn-of-the-century Montana. Working in a mine as a young man, Darby befriends Harley, a fellow who will go on to assist with a bank robbery and hang for it. When Darby realizes that the man responsible for the heist is still free, he vows to avenge his friend. Along the way he courts a Mormon girl, joins the Church, and settles on a ranch near Park City, Utah. The story is quietly stunning; it unfurls slowly, deliberately, washing over the reader like an incoming tide.

That said, I must mention a sentence that ruined this beautiful work for me. Darby’s wife Tilly loses her brother in a horrific accident, and she cries in her husband’s arms. Peterson writes: “He pitied her but that didn’t keep him from taking advantage of her vulnerability and doing what a married man has a right to do.”

I put the book down and went for a walk. I didn’t know if I would be able to pick it up again.

This moment in “Jesus Enough” encapsulates the difficulty I experienced with this collection of stories overall. It is sprawling, beautiful, raw, emotional, human. It is also troublingly misogynistic. Other stories are even more problematic than Darby’s. “Gentleman Stallions” is about Irvin, a man who has to muster up the courage to interfere with his boss’s decision to rape a woman, a stranger, at first sight. The lackadaisical mention of rape is chilling.

“The Return of the Native” focuses on the elderly Rulon who raped his cousin when they were both teens. When she becomes pregnant, her father disowns her and sends her away. Rulon ruined his cousin’s life, and he knows it; he has spent his own lifetime ruminating on it—and the reader is forced to ruminate with him.

Several other stories are about young men who impregnate young women. “Sandrine” is about a young man who nearly runs off with a friend’s wife. “Cedar City” is about a missionary who leaves his mission early to marry the young woman carrying his unborn child. “Bode and Iris” are two unlikely lovers brought together by an unexpected pregnancy. In “Badge and Bryant,” two fourteen-year-old boys make a pact to each get a girl pregnant.

In “The Shyster,” newlywed Arne decides to support his wife Leanne despite her feminist ideals: she doesn’t take his name, she prays to Heavenly Mother, and she works as a lawyer—“a shyster,” according to Arne’s father—who defends sex workers in court. Peterson describes Arne as one who “respected feminists at a distance, but their battle wasn’t his.” Leanne is a much fuller, more complete portrait of a woman than just about any other in the book. But that isn’t saying much, as we only meet her in snatches, and from Arne’s perspective.

The opening piece, “Losing a Bit of Eden,” is the only story that features a female protagonist: Ellen, a middle-aged woman whose husband serves in the bishopric. When their monthly temple trip ends in disaster, a blizzard forces Ellen into an uncomfortably intimate situation with the bishop. Despite the innocent necessity of their circumstances, Ellen wonders if she has been unfaithful to her husband.

Peterson is often hailed as one of our greatest Mormon writers because his work examines Mormon life with an unflinching gaze. The irony of this book, however, is that while its gaze may be unflinching, its scope is narrow. Peterson is still writing as though the perspective of working-class white men is the only one worth contemplating. Yes, it is important that we see their stories, but including a wider cast of more fully developed female characters and people of color would echo the diversity of the real world we live in—a world Peterson doesn’t seem to want to acknowledge.

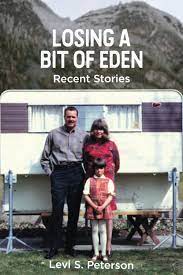

Levi S. Peterson. Losing a Bit of Eden: Recent Stories. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2021. 256 pp. Paper: $14.95. ISBN: 978-1-56085-292-6.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. Please note that there may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and biographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue