Articles/Essays – Volume 34, No. 3

The Proper Order in Which You Found It: from a Brazilian Missionary Journal

September 4, 1999

The bus to Sao Bento up through a complex development of valleys and mountainous jungle. The canopy of trees changes periodically during the slow ascent from the typical street-lining palms to heavier blocked rows of pines; then a tangled, thick, jungle-like fabric of wider trees mixes with hanging moss, vines, and flowering branches. This is then patched with isolated acres of white, pencil-like eucalyptus trees and a darker more majestic body of Pinheiros. These are tall, nut producing pines whose trunks rise up high from the earth and then burst at the top like fireworks with long branches that arch toward the sky and terminate in large green pompoms.

Above it all, the bus reaches a road that follows the crest of the mountain and looks out over the entire series of valleys and hills to re veal hundreds of acres covered in thick and lively banana trees. On steep slopes and irregular tracts, in every possible, imaginable corner there are banana trees in great leafy profusion. They consist of little more than their enormous pastel green foliage, because their stalky trunks are almost hollow, a composite of loosely wrapped fibrous sheaves that blend out into the wide, decorative leaves. New leaves shoot straight up from the center stalk, mature leaves curve downward and are shredded into ribbons by the wind, and dead leaves hang straight down, turn gray and fall off. From the center of the tree comes a sort of purple, tail-like branch, a ball and chain that arches up and gradually weighs the tree over to one side; here, the green ordered bunches of bananas open and begin filling out, all the while hanging upside-down. I have never seen such bananas become what one might consider ripe, but I imagine it would be beautiful, especially with a crowd of Brazilian harvesters, working the long rows with wheel barrels and machetes, hauling enormous mountains of canary yellow bananas in trucks down the hill-side lane. My companion, Elder Thomas, looks out over the vast banana tracts, “Yeesh, I’d hate to be the son of THAT farmer come harvest time!”

Today is a division with Elders Luker and G. Santos from Sao Bento. Just one of the diverse ways we missionaries waste time and mission resources; a division generally requires that one set of companions travel to the area of another (in this case one hour away) to swap “comps” for the day and then come zipping right back to their own area to work, all this only to be repeated the very next morning, trading back. Eight bus tickets in total.

In this division I stay with Elder Luker in Sao Bento while my companion returns to our area in Jaragua do Sul. There isn’t very much planned for today in the way of “choice appointments” or “pure elects” to teach, a fact of which Elder Luker, as host, is surely hyperaware; I’m happy not to be in his shoes. Even though I’m not his “superior,” so to speak, he no doubt wishes he had a few more dependable, secure ideas to try out or places to go in order to keep us occupied and provide opportunities to teach. Otherwise, willy-nilly, days like these tend to fill up with frivolous things.

Of the two appointments that had been firmly scheduled and confirmed, neither comes through, and we are left to search out new activities, new families to teach. Fortunately, Elder Luker does happen to re member one house we could visit and perform service. Finally, we take off on a good half-hour walk just to get there. It’s the home of Emilio and Elizabeth, an old retired couple. We are going to give the man his weekly shave.

As we enter their small home through the mud-room, I see tall stacks of small, red firewood neatly ordered against the wall and a step up into Emilio’s room. From what I can see, he is propped up on a couch, waiting eagerly for his two young friends to arrive, arranging his blanket around himself at the waist. He has a very excited grin on his face as if he’d been waiting the whole morning. Elizabeth, a short, sturdy woman, enters behind us, bringing a handful of chopped wood to put in the stove.

“How good you’ve come! Emilio was just starting to worry about you boys.” She’s a delightful, bustling old gal with long gray hair done up in a bun, wearing a long house-skirt with leggings on underneath and a big wool sweater, whose cuffs are rolled above the elbows. She lifts open the wood stove and wedges the firewood into the small fiery hole, closes it, and replaces a most beautiful, polished aluminum kettle with an aged wooden handle. Elizabeth then works her hands clean on the front of her house skirt and turns her full attention to us, gives me her hand and shakes firmly. She has the most piercing blue eyes and a soft, sweet smile.

“Emilio so wants to have a shave, you don’t even know how badly!” Her voice sounds warm and she is absolutely charming. I am so taken by my encounter with her that I hardly notice that Elder Luker has already sprung into action. He brings from the corner of the small room a wheel chair and wheels it around as if it were a go-cart, trying to get an even wider smile across Emilio’s face; he announces in a radio-like voice that the shaving time has arrived, “Would all persons involved please take their places and get ready for lift-off in ten—nine—eight—seven. . .” Emilio begins to quiver with excitement and sets about getting himself situated for “lift-off.” He roughly rubs his whiskery face up and down with his bony hands, stretches his arms to the sky, and begins to turn his back toward us and the approaching wheelchair. Elizabeth moves forward to assist him, removing the gathered blanket from his lap to reveal his naked, white lower quarters. She removes his withered genitalia from a catch basin and dabs him off with a wash rag, preparing him to be lifted into the wheelchair. Emilio has no legs.

We hoist this gentle, abbreviated man into his chair, and he shimmies back into his seat to assure excellent posture. Elizabeth immediately arranges a towel around Emilio’s lap and explains to me that he’s been seven years without legs, but she doesn’t say how this happened. From the small basin on the side of the room, Luker retrieves a shaving bowl and brush and also a bar of soap and Gillette razor. With his pocketknife, he shaves off soap into the bowl and pours in a splash of the water that Elizabeth is warming on the stove. As he begins to lather the soap with the brush and daub it onto Emilio’s face, Luker hums the Brazilian hymn of independence and waltzes about the back of the wheelchair. Elizabeth offers me a chair on her side to sit and watch the job. She talks ever so intently with me. Her big bushy eyebrows rise and fall as she graciously queries me about my home in the United States.

I get an even better look at the room and discover fine details that bring the room to life with the 40-years of history that have passed since they built their home. The floor has a perfect, waxed shine from years and years of wear and polishing, the enormous, cast-iron wood stove has been kept perfectly clean in spite of countless meals, the gleaming jars of pickles and baby onions done up in that very room in a large pressure cooker are stowed above the hutch, and on the cupboard sit aged frames, photos, and stopped clocks. What unusually calm, dulcet moments these are with our light conversation. I drift in and out, from reality to reverie, the sound of grandchildren wrestling and playing in the yard, Elder Luker’s light humming, and the whisper-like chuckle of Emilio, responding to his tickling barber’s touch. Beyond the quiet, splashing rinse of the razor in the wash basin, the cool afternoon breeze breathes in and through the open window, giving the white curtains body and life.

Elder Luker finishes the shave and playfully buffs off the last of the soap lather from Emilio’s face. He then wraps his hand towel over the man’s head and asks, “How long since you joined the convent, sister?” and Emilio just melts with joy. Elizabeth reminds me that missionaries from our church have been shaving Emilio weekly for more than five years.

As Elder Luker applies the finishing touch, a light dusting of fragrant talc, Elizabeth says, “They say the world is gonna end on Wednesday according to some ‘Nostra-day-mus’ fella. You think that’s true?” “No,” I smile, “I think everything’s going to stay right like it is.”

February 9, 2000

“When using the toilet,” says the sign posted just inside the privy door of the Prochnow house, “flush.” Eunice Prochnow has her own eccentric approach to everything, and leaving long, over-detailed instruction notices around the house for her careless husband and two sons is apparently her favored means of self-expression—they’re everywhere.

“Should you happen to dirty the bottom of the bowl or dribble on the rim,” the sign continues, “scrub it clean with the small toilet brush, and wipe the rim with a bit of toilet paper.” Reading this notice for the first time, I am startled to attention from what had been a moment of dizzy-eyed relaxation and relief of the sort that follows a hot lunch before an unbearably hot afternoon. I stop reading, evaluate my performance, assume a better stance, and correct my aim as if I were being watched, graded.

Beyond the door, I can hear Eunice begin to clear away the wreckage from one of her crash’n’burn lunches for us missionaries: over-fried, breaded steaks, black beans and rice (abnormally cooked in the same pan to give a uniform blackness to both), finely chopped cabbage sprinkled with vinegar and salt, shredded carrots, pineapple slices for dessert, and to wash it all down, a strange pineapple juice she makes by boiling the fruit’s husk. It’s the same meal every time because we eat here only on Mondays, and Eunice’s menus are governed by her fixed rotation. Still, I doubt her food is any less quirky on the other days. I listen and hear her fill the sink to begin washing the dishes.

Leopoldo, her brusque and mischievous husband, has resumed his project of tearing down the rotten, termite-ridden ceiling in the kitchen, which, of course, is directly above Eunice’s own workspace. I can already hear them return to the murmurs and bickering in which we found them engaged when we first arrived for lunch. They are an odd couple. They each carry on whole meaningless conversations with nothing but thin air. To be frank, I don’t know how Eunice managed to put lunch on the table today because when we arrived, Leopoldo was just descending the ladder from a gaping hole in the attic floor clear down through the kitchen ceiling, and looking as though he’d just kicked his way through that very instant. Reaching the bottom of the ladder, he got out his broom and began to gather a lot of rubble and dust—termites fabricate dust—into the corner of the dining area. Miraculously there was no dirt to be found on the kitchen table; only plates, forks and overturned glasses with paper napkins tucked up inside each one, Eunice’s signature touch. She busied herself over her boiling pineapple-husk punch and didn’t see us come in, but finally recognized our presence and shook our hands in greeting. Her glasses were fogged by the steam of her stove-top creations. She has a very humble, motherly look and always seems pleased to receive our visit.

We deposited our book bags in the parlor and went to wash our hands in the bathroom—strangely separate from the privy, another Prochnow quirk—just off the kitchen area. On returning, I found Leopoldo walking around the perimeter of the kitchen tapping each tile near the top of the walls, no doubt to estimate how many he would need to replace in his project. Each time he crossed paths with Eunice, he’d raise a scuffle and say, “Woman, Let’s eat! You’re holding me up!” never taking his eyes off his own project overhead. Leopoldo wears thick, black-framed glasses; has a big, cartoonish nose with pronounced cheek bones; and speaks with a wily tone, harshened by his years of heavy smoking. Occasionally when Alvoro, their youngest, red-headed son of 17, passed by attending to his chores, Leopoldo piped up, “Son, don’t you plan on leaving this house this afternoon! You’re staying right here to work on this project I’ve started.” Alvoro responded with a compliant silence, knowing only too well what a new project of his father’s means. A strapping, sociable teen, he gave us a look that said, “might as well cancel my plans for the whole week.”

Eunice’s frying pan hissed sharply as she put the first of the breaded steaks down to fry. She’d laid out a cockeyed line-up of flour, beaten egg, and bread crumbs—all out of order—through which she transferred each tenderized piece of meat, soon to become tough shoe leather on a plate. She softened the atmosphere a bit with her melodious humming of Primary hymns. Eunice is the director of the Primary music and classes at church, a calling which she takes very seriously. Two times a week, she puts on her walking sandals and hikes all over town to visit the branch children, especially those of less-active families. She delivers a spiritual message and sings Primary songs with the children, like a grandma come to visit. She also puts great effort into preparing stenciled lyric posters for each song, which she mounts on the easel in the Primary room each week, helping the kids learn the words faster. She invents and publicizes grand Primary social activities, which no child attends other than her own granddaughters.

Leopoldo, a non-member, is contemptuous of Eunice’s participation in the church and has little tolerance for church talk at his lunch table. If the subject is mentioned at all, however, it’s usually by him:

“You Mormons just like to party and spend money!” he’ll say all of a sudden. “You don’t see me hoppin’ on a bus to Sao Paulo for a five day jaunt in the city,” to which Eunice cries in defense, “It was to the temple, Leo, it’s not a party!” having just returned herself from a temple caravan.

“Oh no,” he says in reproof, waving his index finger in her face, “you won’t see me getting baptized, not unless the church gives me $300,000!” Much of the time he’s merely kidding around, but when it comes to money matters, there’s always quite a bit of real sentiment behind Leopoldo’s comments. He lives every day indignant over the fact that after “twenty-eight years, eleven months and twenty-seven days” of work (as he has so often rehearsed to us) at the local steel factory, he was short-changed on his retirement. Considering himself pensionable at three Brazilian salaries (equivalent to a monthly $R300 plus and appropriate for 29 years of work history), Leopoldo raves at the injustice in his receiving only one salary, a monthly $R136, give or take—in other words, minimum wage for the rest of his life. This is not what Leopoldo expected, and even if it means no more than playing the poor man’s lottery every day or complaining to anybody who is willing to listen till he dies, Leopoldo refuses to accept the lot he’s drawn. He will not be happy.

“The whole justice system in Brazil’s a damn lie!” he’ll finally say, bringing his fist down onto the lunch table. Today Eunice actually gets up the courage to respond, “All right, Leo, we’ve all heard how you feel, now just be quiet and let everybody enjoy their lunch in peace!”

We take our seats at the table and Eunice invites one of us missionaries to give the blessing on the food, for which Leopoldo grants a brief moment of reverence. Following the prayer, he begins by serving his own plate and mutters under his breath, “In the poor man’s house you eat everything there is, and then you suck your thumb afterwards in hunger. You wanna help me out? Gimme $100,000 and see if that doesn’t make me smile! I need to buy a new faucet for the sink, a new wardrobe and dresser, a helicopter and cruise liner,” and his list goes on.

On the cabinets above the kitchen sink is written: “To all members of this household WITHOUT EXCEPTION: If you dirty a plate or any other kitchen utensil, wash it after use.” As if communication problems with her husband weren’t enough, Eunice has yet another considerable challenge living under this roof, to whom this particular notice is directed. Alexandre, her oldest son, is on almost all accounts “the exception” to her rules. The way the family talks, one might think Alexandre were a story book character, like the Billy-goats’ Gruff or Beauty’s Beast. As we sit at lunch, we can see into the parlor where a door to one of the adjacent bedrooms is forever closed; it is a room toward which many gestures and vague, soft-spoken comments are directed. It is Alexandre’s room.

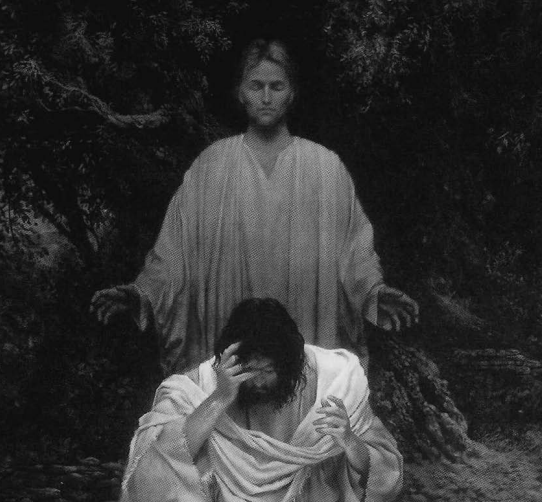

In 1990, Alexandre returned from his mission in Porto Alegre Brazil on foot with nothing but the clothes on his back. Something on the mission had changed him—something drastic. He entered his room and shut the door for weeks at a time. He became a total recluse, hiding away from the world behind his closed bedroom door. He left, of course, to tend to certain necessities, even to run errands in the neighborhood, but he never mentioned even a word in passing as to what he was doing or where he would go. For many months he ate only pork and beans and other canned foods, setting the empty cans outside his window for disposal. With time he began accepting his mother’s food, but only if it were leftover after every one else had eaten and cleared out, and even then it had to be in a special Tupperware container, placed at his end of the table, before he’d touch it.

When the subject comes up today (as it inevitably does every time we visit), Eunice leans toward us at the table and in a concerned whisper says, “He’s writing, Elders.” Her look turns very serious. Leopoldo doesn’t pay any attention and keeps on eating.

“He fills whole notebooks with. . .writings.” She seems to experience some difficulty, is reluctant to release the words in her own mouth. Finally she manages one word, “Prophecies”—and then another few— “about the last days”—and then she tells me the craziest stuff I’ve ever heard.

Alexandre thinks he is God’s chosen prophet. But not just any old prophet. He is one of the two witnesses mentioned in Revelations 11:3-14 who will be murdered in the streets of Jerusalem, whose body will lie three days before the temple to be seen by all, and who will resurrect on the third day as an apocalyptic sign to the entire world. He receives and records his prophetic visions in notebooks, which fill his desk drawers and shelves. What little she understands of this, Eunice has gathered from passing comments and from snooping around while Alexandre was out of the house.

“The door to his life has literally been shut for ten whole years, Elder,” she explains to me, continuing the conversation after lunch. She digs out a pile of black binders in which she has gathered all of Alexandre’s mission letters and clippings; she’s saved everything, together with her own extensive journal entries that talk about the family and each of her sons. She’s begun to trace the changes she observed during the last year of his mission, trying to discover what it was that has left him in his current condition. She shows us letters in which he wrote everything in senseless rhyme and riddles, letters in which he opened fire on her with abusive language, and finally letters where he wrote nothing at all— blank pages only. She handles each page with equal love and gentle care. I can only imagine the fear and sadness she must have felt as the distance between her and Alexandre became greater with each correspondence and, worse, the horror she experienced when he came home, a lunatic.

“Little by little, though,” says Eunice with a new look of hope, “he’s opening the door again. He doesn’t run to his room so quickly when I enter the kitchen, but sits with me, if only in silence. He talks a bit here and there, but says he can’t tell me anything more about his calling or what he must do. But he’s talking with me, Elder, for the first time in 10 years, Alexandre’s talking again!”

Leopoldo shows no interest or sympathy during our conversation, but walks in and out of the parlor area, adding his brutally humorous comments and gestures, all of which carry an expression of lost cause— nothing-to-be-done. He is, in a sense, more apocalyptic than his son. But

Eunice has a hope and faith that to me are remarkable. In practical fact, the more she learns about Alexandre, the more reason she has to worry. (He has even confessed to having felt inspired to kill the family and then himself, to which Eunice responded by hiding all the knives in the house.) Even so, the woman prays for her son as if he were still far from home, on his mission even, with perfect hope that one day he will return completely to his mother’s love. Closing her binders and scrap collections, Eunice embraces them as if each represented her particular love for one of her distant children, and concludes, “My sons are all special.”

Inside the privy door, the notice continues: “After cleaning toilet, throw the toilet paper away, and rinse the brush in the sink. Then return both the brush and the bathroom carpet to their proper places, lower the toilet lid, and turn off the light. Keep everything in the proper order in which you found it.”

I’m happy to comply with these house rules and almost ritualistically check-off each task with a sort of reverence, feeling that Eunice’s rules deserve to be respected (though in reality I haven’t made the least bit of mess). It is, after all, the house of a family, if not of a prophet. It is, in either case, a sacred place.

Back in the kitchen I find Leopoldo unbuttoning his shirt to take it off and work. He’s just finished bragging that, though he has a 60 year old face, his body remains that of a 17 year-old boy in his prime. To look at him, his tight and sickly torso, you’d think he’d spent eight weeks in a smokehouse, strung up along side of some carp. He resumes scrutinizing his project overhead and Eunice continues to clean up. We make our way to the door, thanking them for the meal and hospitality. We are unaware of a new presence that has arrived at the back door of the kitchen. Only when I shake Eunice’s hand once more in thanks and turn to exit the house am I startled to see him.

He’s been patiently waiting outside the screen door since he arrived and saw me leaving the bathroom. He hasn’t said a word, nor entered the kitchen. The two of us stare at each other for a second or two—long enough for me to focus on him and see he’s not the strange specter I had imagined. He is very normal, if a little pale, and manages even a polite but conscientious smile. I can tell he’s been jogging and is now returning, dressed in shorts and running shoes, a bit sweaty. He reaches to open the door, and I reach out to assist, holding it open for him. After a moment’s pause, he enters the kitchen and says only, “Excuse me,” in a normal, normal voice. He then crosses the kitchen, steps through the parlor and into his room, and closes the door.

May 3, 2000

Walking back from church on Sunday, we saw a red truck pull over about 75 yards ahead from whose passenger-side window was thrown a white plastic grocery sack before the truck sped off down the road. We were on a stretch of highway that’s tended only by vultures, crabs, and other scavengers and is, thus, a safe and popular dumping ground for trash. Few people even pass through there on foot, so we missionaries were the first to arrive after the truck and came upon the abandoned grocery sack, whining and meowing in the grass.

Three kittens, not two days old with eyes still tightly locked shut, pawed at their prison’s plastic walls, desperate for the warm, familiar presence of their mother. I opened the bag and took them out, all three in one hand, and their meows grew all the more shrill. Their delicate heads balanced on frail necks, and fine claws clung to each of my giant fingers. I set them back into the bag gently, stood again, and surveyed the dilemma. So far from the neighborhoods of compassionate children or sympathetic passers-by who might come to their rescue, I knew they’d surely die. I couldn’t think of anyone who might take care of them and debated whether it was even a good idea for us, as missionaries, to be seen toting a sack of kittens into a residential neighborhood to drop off on some curb or street corner where they would stand a better chance of rescue.

A man approached us from behind. He looked as if he were return ing from hard work, wearing scruffy clothes and missing all his front teeth. He too stopped to look over the scene. We explained the situation to him and our reasons for indecision, but he just kept shaking his head and murmuring, que pecado, “what sin.”

Finally, in what seemed compassionate valiance, the man took action. He gathered the three up in the bag and tied it twice. It ballooned tight with trapped air, and I asked if he ought not poke a little hole in the bag to let the little ones breathe, which he did. Relieved to see that this man was more willing than we were to handle the situation, my sense of injustice or danger subsided, and we walked along beside him, talking. I began to hope that perhaps our good Samaritan was a special contact whom we might end up teaching. But when we reached the small bridge that passes over our river-like ocean inlet, the stranger gave the sack of kittens a light toss and quipped, “We’ll see if they can swim!”

I stopped and my stomach knotted again to watch the package splash down on the surface of the water and become caught in a circular current; it swept out a little ways, then back again, afloat but out of reach. The man had continued on, laughing at our silent dismay and proud of his cruelty, but we looked on. I could hear the kittens’ cries become more frightened as their balloon-like plastic sack filled with cold water through the very hole I had suggested be made. Only a minute passed and their cries were gone. Though I could still see one kitten helplessly paw against the inside of the sack, I knew he would soon succumb like the others. At our urging, a nearby fisherman rowed over to fish them out, but found them already dead and tossed them back.

Kitten death. A thing that’s absolutely common and everyday—unbearably worse crimes are committed in the name of supper—but all the same, it was sobering and pitiful to watch. It might have been better, I thought, not even to have stopped for the kittens in the first place.

May 5, 2000

Church was good Sunday—well, average. We’re going through a stage of abnormal normality: no great jumps or falls in attendance but also never the same crowd. Members come one week but skip the next, and oddly there is always someone there back from a lengthy absence. The people we visit during the week and commit to come to church on Sunday never show up, yet other people whom we haven’t visited for weeks just turn up like stray dogs. The surprises and disappointments combined are so maddening any more, I don’t even know what to pray for.

Our backbone (and it’s a weak one) is made up of one or two stock families whose children have also married, hung around and multiplied the family headcount in church. In the case of Eunice Prochnow’s family, they have as many as four generations there on any given Sunday: 1) her deaf mother Judith doesn’t miss a week, 2) Eunice, herself, attends (sometimes even managing to bring cantankerous old Leopoldo, her non-member husband), 3) her two sons Alvoro and Arnaldo are there, and Arnaldo brings his wife and 4) daughters, the great-grand-daughters of the bunch.

Then Lindomar Salvador provides not only his family (wife Ana and mentally retarded daughter Eliane), but also three more, the families of three children, whom he married off before they were really prepared. They’re all good people, individually, but as a family can’t manage to keep one another active in church, and recently they are slipping through the cracks. Still, they make up a good 40 percent of our branch on any given Sunday.

The rest are stragglers. Espinheiros Branch separated from the Boa Vista Ward only three years ago and has since experienced a period of rapid cancerous growth. A succession of ambitious missionaries passed through and inflated our church rosters with scads of unmarried women, 8-year-old kids without their parents, and generally unconverted new members. Today those new members, together with the ambitious missionaries have all disappeared, with the exception of one shining family: that of our Branch President Sinval and his wife, Salete. The number of baptized members is more than high enough to justify a ward and the building of a chapel, but the number of active, tithe pay ing, worthy members hardly even justifies the expense for rent or light and water bills in our regular meetinghouse. In fact, the stake president has given us till June (when our rent contract expires) to grow or close.

This may seem like late notice, but only because I’m reporting on it one month away from our deadline. In reality, we’ve known about this possibility for over five months. At first we kept it a secret among the branch presidency, the quorum president and us missionaries. No one talked about it, either from disbelief that such regress could or would occur, or because some leaders, in fact, wanted Espinheiros to close; there are of course those who, in their heart of hearts, would prefer to re-unite with our mother-ward, Boa Vista, take a back seat in every meeting and never lift another finger. Many of the leaders seem soured by the weight of responsibility that has stranded them out here in the swamps.

So what do we do? We try to visit members as much as possible, to encourage them in their callings and at least to appear coordinated, united, and resolved. But, in fact, we do our work in our way, and the branch leaders tend separately to theirs—and everybody ends up doing pretty shoddy work. Sunday, we all show up at church to see how the cards will land.

We missionaries head off walking Sunday mornings at about eight a.m. to arrive at the meetinghouse by quarter to nine. If we’re lucky, one of our member families will drive by midway and offer us a ride. This week, it was Lindomar. His car was already packed with his wife Ana, daughter Eliane and a gang of grandkids whose parents had all stayed at home in bed. I ended up sharing the front passenger seat with my companion, and we had to straddle the semi-transparent gas tank that Lindomar has rigged up inside the cab. His gas gauge is shot, so he monitors the fuel level by keeping the tank right where he can see it (at our feet), illegal though this may be.

Rounding the corner to the church’s street, Lindomar pulled off at a bread store to buy a can of soda as a bribe to soothe the mischievous Junior, a five year old grandson, who’s not been known to behave during a single sacrament meeting without it. It’s a small, pragmatic indiscretion, Lindomar’s buying things on Sunday, but nevertheless has been a source of complaint and disenchantment to newer members, who pass by that same bread store and see his red Chevy and him coming out with his hands full. Even so, Ana felt it necessary to emphasize to little Junior, as he sat on her lap waiting for his grandpa to return with the soda, that this was “a strictly one-time thing,” and that “we do not buy things on Sunday because its the Lord’s Day.” No sooner had she said this, than Lindomar re-entered the car, delivered the purchase, and started the engine again. “What are you talking about, Grandma?” said Junior, “You and Grandpa stop here every week on the way to church!”

At church, Branch President Sinval usually arrives about fifteen minutes before anyone else and opens up all the doors and windows to air things out. He’s a dedicated worker in all he does, but he becomes nervous and timid on Sunday. The sooner he manages to delegate his responsibilities to other people and escape the spotlight, the better he feels. The poor man has reason to feel this way. When Sinval had been a member for only four years, the previous branch president (a shifty fellow I’m glad I never knew in person) called on him at his house late one evening, the night before that man suspiciously and secretly moved out-of-town. He delivered all the leadership manuals together with the calling of President. Since then, Sinval has struggled to perform even the basic mini mum that the job requires in the face of a congregation, whose members are mostly older and more experienced than he is. Whether it’s conducting meetings, teaching classes, or even giving talks, his game-plan of pushing off Sunday tasks to others has become so strategic, I begin to worry that he just might be scheming an exodus like his predecessors. At the rate that necessity calls on him in this small branch, it would not be hard to understand why.

Classes are poorly improvised, most often by Lindomar or occasion ally by his son Edson, should he decide to come to church. Edson sits in the back of the Priesthood quorum, studying the manual for his adult Sunday-school class because he hasn’t opened the book since last week. He can do this because he’s a returned if fallen missionary with a pull-it off-at-the-last-minute attitude. He has enough knowledge to impress with just enough ambivalence to confuse, and our lessons always turn out lifeless and uninspiring. Besides, everyone knows that the moment church gets out, Edson will race home and get changed to go out and play soccer Sunday afternoon.

This week’s lesson was proceeding sleepily until the subject of baptism came up and the discussion developed as to why certain church denizens come out every week but never take the plunge. One of our finest families, that of Carlos and Lenira, sits right up front in every meeting but for some mysterious reason (that nobody knows and they won’t reveal) has not been baptized into the church. Well, so much talk about the B-word made old Leopoldo’s ears ring, surely thinking people were talking about him, a non-member. Finally, after about all he could stand, he piped up from the back, “It’s because this is all a damn lie, that’s why! Oh, I’ll be baptized, all right—just gimme $300,000!” He accompanies his family to church every now and then to escape his own loneliness at home, but he doesn’t want to accept anything that is taught there.

“Well Leopoldo, when are you planning to be baptized,” asked someone on the other side of the room, “when you are old and dying?”

“Of course not,” he responded, “only AFTER I die!”

A sister in front of me leaned in to her neighbor’s ear and whispered, “In this church that’s okay too, isn’t it?”

Valdir always arrives late but in time for sacrament meeting. He was excommunicated and lost his priesthood when he paired off with young Cristiane and started making babies. Now they both come to church together like Bonnie and Clyde, and everybody’s head turns when they come skipping in the door. Valdir comes dressed in a Sunday best that’s altogether different from his greasy work duds; he even wears a dentured, Cheshire-cat-smile that’s different from his grin on other days of the week and makes his lips bulge ever so slightly. Cristiane, not half his age, wears tight-fitting short skirts and shoulderless blouses and snaps at Valdir for not keeping his hands to himself on the family pew—a not so-careless indiscretion which has also perturbed our newer, still innocent members. They certainly never expected to see sin practiced casually in church.

Mix in one good dollop of gossip and member rivalry and you pretty much have our little branch. Family-home teachers have ceased to exist, as well as the visiting teachers. The youth have no seminary teacher, and we Elders end up giving almost all the talks. The apathy in the group is enough to make one think they’ve all quit and gone home already.

And so, as the comedy draws to a close each Sunday and we’ve all had about as much as we can stand of each other, I drive the closing hymn home as branch music director, sometimes even making wanton leaps to the last verse to get things over with. Lindomar’s retarded daughter Elaine keeps right with me; she can’t read music but has perfected a convincing, mimicking sing-along technique. Some days it’s just us two singing—me, trying to resuscitate the group, and Eliane, starving for attention. This week, when Lindomar snapped at her to pipe down from where he was seated up front, Eliane expertly gave him the middle finger gesture and kept on singing our duet, only a little bit louder.

Then, leading the final chorus of “The Spirit of God” to ring down the curtain, I alone from my position in front saw a stray yellow dog come in off the street, pause for a moment in the entry way at the rear of the chapel, survey the situation, lift his leg in high ceremonial fashion, and mark his territory on the branch bulletin board before wandering off again out of sight.

Despite all our quirks and glitches—I’ve never worked in an area that didn’t have such problems—I have come haltingly to love these people, even the craziest and most heretical. The mere thought of closing Espinheiros Branch tempts me to regret having come here in the first place. In reality, no one is completely certain what the Stake President will do; some say he wouldn’t have the heart to close us down. But there definitely are signs to make one worry.

After the closing prayer, the branch members evacuate the chapel as if the place were going up in flames. They are in such a hurry to get on with the rest of their day. Outside the sun is glaring and directly overhead at noon, yet the air is becoming quite cool and crisp. The sky is always somehow perfectly clear of clouds on Sundays, and there is a light breeze mixing good autumn smells in the air.

Somehow we missionaries don’t manage so many free rides going home as we do coming to church, but I don’t mind, given the pleasant weather. We set out walking again on the main road, keeping company only with the buzzards and crows that perch one by one atop telephone poles or circle overhead in large funnel-like swarms. They congregate by the dozens and wait with patience for the coast to clear before descending on some roadside delicacy. Up ahead we see one such swarm circle lower and lower, there beyond the little bridge that passes over the dark, cool waters of our inlet.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue