Articles/Essays – Volume 21, No. 1

The Prosecutions Begin: Defining Cohabitation in 1885

The prosecution of George Reynolds in the mid-1870s and the United States Supreme Court’s 1879 affirmation of that conviction are usually viewed as the key legal events leading to mass prosecution of Mormon polygamists in the late 1880s. While Reynolds v. the United States (1879) seemed to dis pose of the crucial first amendment defense relied upon by the Mormons, it did not lead to the prosecutions. Rather, they were triggered by the passage of the Edmunds Act in 1882 as well as a major Supreme Court decision in 1885 over the cohabitation prosecution of Salt Lake Stake President Angus M. Cannon.

When Reynolds was first prosecuted in 1875 there was no crime of cohabitation on the federal statute books. Only polygamy was a crime and could not be prosecuted without proof of a marriage ceremony, evidence almost impossible for prosecutors to secure. Enforcement of the anti-polygamy laws in Utah was a “dead letter.”

At least until 1885 and the Angus Cannon prosecution. When Brigham Young and Orson Pratt delivered the first public sermons on polygamy in August 1852 (Arrington 1985, 226; Van Wagoner 1986, 84), they were making public a principle revealed to Joseph Smith, Jr., in 1843 (D&C 132) but practiced with the greatest secrecy (Van Wagoner 1986, 1-69; Foster 1974). The sermons set in motion events that resulted in forty years of confrontation with the federal government and would threaten the Church’s very existence.

In spite of later national outrage, it was apparently not a crime in the early Utah Territory for a man to marry more than one woman at a time. The Mormon-dominated legislatures of the initial State of Deseret and its post-1850 successor, Utah Territory, protected the practice. Because Utah was a territory and not a state, Congress had absolute power to govern, regulate, and even dictate the affairs of the area and its citizens.

On 1 July 1862, Congress entered the picture by enacting the Morrill Anti Bigamy Act, named after Congressman Justin Morrill (Van Wagoner 1986, 107; the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, Ch. 126, 12 Stat. 501, hereinafter the Morrill Act). Bigamy, defined as having one undivorced spouse living and marrying another, was to be punished by a maximum five-year prison sentence and a fine of $500, making it an apparent felony (Sec. 1). In addition, sections 2 and 3 of the act annulled articles of incorporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as passed by the legislature of the State of Deseret. Thereafter, the Church could not legally hold more than $50,000 worth of property, with the excess subject to seizure by the federal government.

Enforcement of this act was spotty to nonexistent, probably because the Civil War and Reconstruction preoccupied federal authorities and because of local gentile political infighting (Goodwin 1913, 42-47).

In 1874 Congress tried again with the Poland Act (Ch. 469, 18 Stat. Part 3 253). This act organized a more effective enforcement mechanism in the territory through the offices of the United States Attorney and the United States Marshal (Sec. 12). It severely limited the jurisdiction of the Mormon dominated probate courts and required that polygamy prosecutions, as well as all other criminal matters, be heard in federal territorial district courts (Sec. 3). The Territorial Supreme Court was empowered to appoint “commissioners,” or magistrates, to assist them (Sec. 4). We should keep in mind that members of the Territorial Supreme Court were federal officers, appointed by the president and confirmed by the United States Senate (An Act to Establish the Territorial Government of Utah, Ch. 51, 9 Stat. 453, 456, Sec. 11 [1850]).

The following year, George Reynolds, polygamous secretary to Brigham Young, was handpicked by Church leaders as the first to test the new statute (Van Wagoner 1986, 110-11; Jensen 1:208-9). Reynolds was convicted in 1875, but the decision was reversed on appeal because of a defect in the grand jury process unrelated to polygamy (United States v. Reynolds. All court cases are listed in the bibliography under “Mormon Polygamy Cases.”). The second trial (1876) again resulted in a conviction, this time affirmed by the Territorial Supreme Court.

The subsequent appeal to the United States Supreme Court, Reynolds v. United States (1879), resulted in the landmark freedom of religion ruling which held that Americans had the right to any religious beliefs they wished, but that Congress had broad powers to limit the practice of those beliefs. Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite wrote for the majority: “Can a man excuse his practices to the contrary [in violation of law] because of his religious belief? To permit this would be to make the professed doctrines of religious belief superior to the law of the land, and in effect to permit every citizen to become a law unto himself. Government could exist only in name under such circumstances” (pp. 166-67; see also Lee 1985 and Clayton 1979).

Thus, polygamy was not protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, and Mormons were in for many years of trouble. The court battles became so protracted, in fact, that the United States Supreme Court ruled on at least eighteen Mormon polygamy cases between 1879 and 1891. (See case list in bibliography.)

But even the 1879 Reynolds decision did not bring about enforcement of the existing anti-polygamy laws. President Hayes viewed this gap between law and practice as the result of “peculiar difficulties attending its enforcement,” calling the law “a dead letter in the Territory of Utah.” He was an advocate of withholding “the rights and privileges of citizenship in the territories of the United States” as a prosecutorial club, and he opposed Utah statehood until the issue was resolved (Richardson 9:4512).

The following year, 1880, President Hayes urged a kind of citizenship death penalty on the Mormons in an effort to completely purge the courts and government of the territory of them. The president urged these draconian measures because:

The Mormon sectarian organization which upholds polygamy has the whole power of making and executing the local legislation of the territory. By its control of the grand and petit juries it possesses large influence over the administration of justice. Exercising, as the heads of this sect do, the local political power of the territory, they are able to make effective their hostility to the law of Congress on the subject of polygamy, and, in fact, to prevent its enforcement. Polygamy will not be abolished if the enforcement of the law depends on those who practice and uphold the crime. It can only be suppressed by taking away the political power of the sect which encourages and sustains it (Richardson 10:4558).

On 4 March 1881, President Arthur A. Garfield in his inaugural address said, “The Mormon Church not only offends the moral sense of manhood by sanctioning polygamy, but prevents the administration of justice through ordinary instrumentalities of law” (Richardson 10:4601).

After Garfield’s assassination, his successor, Chester A. Arthur, proclaimed polygamy “this odious crime, so revolting to the moral and religious sense of Christendom” and urged statutory repeal of the traditional spousal privilege in polygamy cases, as well as strict new laws requiring the public registration of all marriage ceremonies (Richardson 10:4644). The president’s recommendation on spousal privilege sought to plug a gap in the law created by the United States Supreme Court in the case of Miles v. United States (1880), one of the few appeals won by the Mormons.

In 1882 Congress addressed all these presidential and judicial admonitions in the Edmunds Act (Ch. 47, 22 Stat. 30). It closed all the remaining loopholes and spelled eventual doom for Mormon polygamy.

The bill was first introduced as a report from the Senate Judiciary Committee, named after George F. Edmunds of Vermont (CHC 6:42). Section 1 again declared polygamy to be a felony carrying a maximum sentence of five years in prison and a $500 fine. Existing law would have required the marriage to have been entered into after the 22 March 1882 effective date of the legislation.

Section 3 gave prosecutors the additional option of a misdemeanor charge of cohabitation with a maximum six-month jail sentence and $300 fine. Jurors who were polygamous or sympathetic to the practice were excluded from sitting on these cases, effectively removing Mormons from any part in deliberations (Sec. 5). Polygamists were declared ineligible to vote or hold office (Sec. 8). In one sweeping provision, Mormons were purged from all levels of government and the courts as Congress declared all elected or appointed offices vacant and annulled all existing voter registration (Sec. 9). The president of the United States was awarded broad authority to make deals for amnesty with any Mormons prepared to break from the Church (Sec. 6).

In enacting this sweeping prosecutorial weapon for use against the Mor mons, Congress apparently gave little thought to defining the newly created crime of cohabitation beyond stating that it could only be committed by males. Unlike felonious polygamy, no definition of cohabitation was written into the statute. The critical Section 3, in its entirety, read: “That if any male person, in a territory or other place over which the United States have exclusive juris diction, hereafter cohabits with more than one woman, he shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, on conviction thereof shall be punished by a fine of not more than three hundred dollars, or by imprisonment for not more than six months, or by both said punishments, in the discretion of the court.” The earlier Poland Law stipulated that prosecutions under the Edmunds Act would take place in the relatively hostile federal territorial district courts. On 22 March 1882, President Arthur signed the Edmunds Act into law.

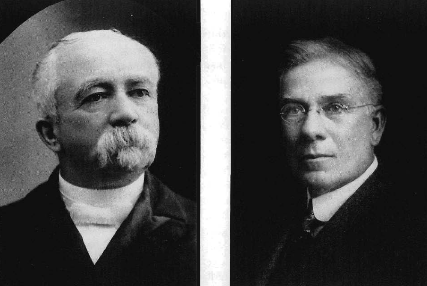

While this ferment was brewing, Angus Munn Cannon was living a life that would mark him as one of the most faithful of Mormons. It would also make him an inviting target for these newly armed federal prosecutors.

Cannon was born in Liverpool, England, in 1834, the fourth child of George and Ann Quayle Cannon. His parents later joined the Church, moved to the United States, and settled in Nauvoo where Angus was orphaned as a boy. He, a younger brother, and a sister moved in with a recently married older sister. As a youngster he apparently knew the Prophet Joseph Smith and attended school with the Smith children.

At age twenty, while living in Utah, he was called to serve in the Eastern States Mission. There he labored with the likes of Parley P. Pratt and John Taylor. During his mission he was offered an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, the first young man from Utah given such an opportunity, but he declined, preferring to continue his mission. In 1861 he was called, along with his young polygamous families, on a “Cotton Mission” to the St. George, Utah, area where he quickly established himself as a leading citizen. Throughout his life, he served in several public positions, including prosecuting attorney for Washington County, Salt Lake County Recorder, and business agent for the Deseret Evening News. His brother, George Q. Cannon, was a member of the First Presidency of the Church (Evans and Cannon 1967, 189-216;Jensen 1:292-95).

On 6 April 1876, Cannon was called by President Brigham Young to serve as president of the Salt Lake Stake at a time when it included Salt Lake, Tooele, Davis, Morgan, Summit, and Wasatch counties. He held this position for twenty-eight years (Evans and Cannon 1967, 212-13). Thus, by the mid 18808 Cannon was at the top of the second echelon of Mormon leaders.

Like many Mormons, Cannon was not anxious to embrace polygamy when it was first suggested to him. His reminiscences of a 12 October 1905 evening in Salt Lake City with his boyhood friend Joseph Smith III, son of the martyred Prophet, show what a struggle his conversion to it was. Smith was president of the Reorganized Church at the time and was on one of his many missionary swings through the land of the “Brighamites.” Cannon had not seen Smith since he was ten and young Joseph was twelve in Nauvoo. However, a friend had pointed Smith out to him at an earlier Conference meeting (Turner 1985, 450-56; Cannon 1905, 1-26). Cannon’s reminiscences describe his own conversion to the plural marriage system and his efforts to convince the RLDS leader that polygamy was a doctrine initiated by his father, the Prophet.

Cannon recalled that as a young man, an older sister of his had been courted by an unnamed elder who was already married. Furious, he con fronted the elder, determined to defend her honor. The elder assured him that the principle of plural marriage was a doctrine of the Church and that his proposal was in no way immoral.

Cannon recounted how he discussed these events with his aunt Leonora Cannon Taylor, the wife of Apostle John Taylor, who disclosed to Cannon her knowledge of and belief in polygamy. In September 1852, Cannon said he attended a Church meeting where he heard Church official William Clayton read a revelation on the subject. Shortly thereafter he withdrew his objections to his sister’s married suitor, though he remained troubled by the doctrine (1905,5-7).

As he came to accept the principle, he decided that it would be best to enter into it only when he found two women he could love who were willing to marry in such a relationship at the same time. On 18 July 1858, Cannon did just that, marrying two sisters named Sarah Maria and Ann Amanda Mousley within an hour of each other. He recalled that his was “the first plural marriage solemnized in the territory after the arrival of Johnson’s army” (Cannon 1905, 8-9).

In 1875 he took the widowed Clarissa Moses Mason as his third wife. Then, in October 1884, Dr. Martha Hughes, chief surgeon and resident physician at Deseret Hospital where Cannon served as president of the board, became his fourth wife. Finally in 1886, after his later cohabitation prosecu tion, he married Johanna Cristina Danielson and Maria Bennion. The six wives bore sixteen children by him (Evans and Cannon 1967, 220-36).

Yet, even with this headlong plunge into polygamous life, Cannon apparently held secret doubts. In his reminiscences he said these doubts were re solved when he was called as a witness in the 1884 polygamy trial of Mormon folk hero and later Apostle Rudger Clawson. As he claims to have explained to Joseph Smith III:

I was confused when I took the stand for only one minute, when a heavenly influence came over me and filled me with joy that was inexpressible. The same feeling came over me that I experienced at the time I received an answer to my prayer in testimony of your father [Joseph Smith, Jr.] being a Prophet of God, and I answered every question propounded to me not of myself. I occupied an eminence in my feelings and looked upon the Judge [Charles Zane], the members of the court, and the Jury and the assembly that filled the room, with composure and the greatest satisfaction. When I returned to Judge [Elias] Smith and my brother [George Q. Cannon], I said “Brethren, I have felt the power of God accompany me in preaching the Gospel, but I never felt His power in a more marked degree in my life than I have done today on the witness stand in that court.” Now I know what the Lord said to his disciples to be true, wherein he said, “when they arraign you before judges and rules (sic), take no thought what you shall say, for in the hour thereof it shall be given unto you” (1905, 9-10).

Cannon surely realized that he might become a victim of federal prosecutors as the fall of 1884 brought the highly publicized show trials of Mormon leaders LeGrand Young and Clawson. Those fears were proven correct shortly after the new year.

The Deseret News reported on 20 January 1885 that a warrant for Cannon’s arrest on the misdemeanor cohabitation charge had been served and that he was in custody. At the same time, deputy United States marshals had appeared with arrest warrants at the offices of future apostle and Deseret News editor Charles Penrose, but he was not there.

A few days later the Salt Lake Tribune reported that the government had abandoned the more serious polygamy charge and was proceeding under the misdemeanor cohabitation charge only (“Prosecution,” 1885).

A grand jury indictment for the misdemeanor crime of cohabitation came down on 7 February 1885, and on the 13th Cannon entered a not guilty plea (Cannon v. United States, 1885, 1). A jury trial was set before federal territorial Judge Zane for the following April. The case was to be prosecuted by United States Attorney William H. Dickson.

When Angus Cannon saw himself becoming the object of the fondest desires of federal prosecutors, he turned to Franklin Snyder Richards for legal counsel. The choice was a wise and obvious one.

Born on 20 June 1849, in Salt Lake City, Richards, son of Apostle Franklin D. Richards, had been a committed Mormon all his life and was educated in the best Utah schools. In 1868 he married Emily S. Tanner, the only wife he would ever have. Shortly after their marriage, the couple moved to Ogden. He was appointed clerk of the probate and county courts and later elected county recorder as well. His work there was so outstanding that he came to the attention of Brigham Young, who urged him to study law. Richards was admitted to the territorial bar on 16 June 1874 (Jensen 4:55-56). He was one of sixty-eight lawyers admitted to practice before the territorial courts in 1875, the only one residing in Ogden (“List of Attorneys Who Are at Present Residing in Utah, And Submitted to the Supreme Court,” 1 Ut. 377-78).

Richards interrupted his law practice in 1877 to serve a mission in Great Britain (Jensen 4:56-57), but when Brigham Young died on 29 August 1877 in Salt Lake City, Richards returned to represent the Church in extended court battles over the considerable Young estate (See Young v. Cannon, 1880, an appellate decision where Richards was not attorney of record). By 1880 he was retained as general attorney for the Church. That same year he was dis patched to Washington, D.C., to resist Congressional efforts to repeal women’s suffrage in Utah Territory. (Richards and his wife, Emily, remained steady supporters of women’s suffrage, especially during his service in 1895 as a member of the State Constitutional Convention immediately prior to Utah’s admission to the Union in 1896).

In 1881 Richards was admitted to the bar in California, where the Church had considerable interests, and became a fixture in the territorial courts defending the interests of Mormons. In 1882 the Church-sponsored People’s Party nominated him to replace George Q. Cannon as Utah’s delegate to Congress, but he declined. In 1890 he became chairman of the People’s Party to preside over its dismantling. During the bitter Reed Smoot hearings of 1903-8 he represented President Joseph F. Smith through the course of his testimony. Also among his clients was Lorenzo Snow, probably the most prosecuted of all Mormon polygamists.

By faith, experience, and background, Richards was the obvious man to represent Cannon as he entered the hostile confines of the federal courts of Utah Territory.

When the trial began in April, there seemed to be little controversy between Cannon and the federal prosecutors about the facts. The only real issue was how the new crime of cohabitation was applied to those facts.

The trial opened 27 April 1885, and testimony was taken from only three witnesses, all called by the government: Clara C. Cannon, the defendant’s third wife; George M. Cannon, his twenty-four-year-old son by his first wife, Sarah Mousley Cannon; and Angus M. Cannon, Jr., another adult son of his second wife, Ann Amanda Mousley Cannon, sister of Sarah.

These witnesses testified that the defendant owned a large home at 246 First South Street in Salt Lake City. This home was divided into at least three apartments, each with its own kitchen, parlor, and bedroom opening along common hallways. Each of the three wives mentioned occupied one of these apartments. Angus lived in the house also. He was said to be in the habit of dividing his time roughly into thirds, eating meals at the table of his individual wives and those children who were still living with their mothers [Cannon Transcript, 1885, 7-10).

The only controversy arose when Richards tried to question the witnesses as to whether the defendant spent the night or had sexual relations with each of the wives. United States Attorney Dickson strenuously objected at each inquiry, and the trial court sustained the government by ruling that these matters were not relevant to a charge of cohabitation.

A proffer by Richards suggested that had the testimony been allowed, it would have established that with the passage of the Edmunds Act, the defendant announced to his family that he intended to abide by it and would withdraw himself from physical relationships with each of his wives. How ever, he intended to continue to support his wives and to take his meals with them (Cannon Transcript, 1885,8-11).

George Cannon was allowed to testify for the defense that the defendant had married the Mousley sisters at the same time, on a date prior to the enactment of any law making polygamy illegal in the territory (Cannon Transcript, 1885, 10). He did not mention Dr. Hughes, whose marriage was only a few months old and had occurred well after the 22 March 1882 effective date of the Edmunds Act. The government and defense then rested and waived clos ing arguments (“Trial,” 1885).

The final courtroom skirmishes were over jury instructions. Richards offered a series of instructions to the court stating that sexual relations were an element of the new crime of cohabitation, and the government had the burden of proving that such contacts had occurred. Judge Zane did not agree {Cannon Transcript, 1885, 12-15).

The key instruction he did give the jury, over Richards’ objection, was: “If you believe from the evidence . . . beyond a reasonable doubt, that the defendant lived in the same house with Amanda and Clara C. Cannon . . . and ate at their respective tables one-third of his time or thereabouts, and that he held them out to the world, by his language or his conduct, or by both, as his wives, you should find him guilty.” On 29 April 1885, the jury returned a guilty verdict (Cannon Transcript, 1885, 15-16).

Before imposing sentence on 9 May 1885, Judge Zane asked Cannon if he had any statement to make. Cannon replied “Nothing.” The judge then reminded him that he had some discretion in sentencing and said, “I would love to know that you could conform to the law.” Cannon reportedly replied:

I cannot state what I will do in the future. I love the country. I love its institutions, and I have become a citizen. When I did so I had no idea that a statute would be passed making my faith and religion a crime, but having made that allegiance, I can only say that I have used the utmost of my power to honor my God, my family and my country. In eating with my children day by day, and showing impartiality in meeting with them around the board with the mother who was wont to wait upon them, I was unconscious of any crime. I did not think I would be made a criminal for that. My record is before my country; the conscience of my heart is visible to the God who created me and rectitude that has marked my life and conduct with this people bears me up to receive such a sentence as your honor shall see fit to impose upon me (Evans and Cannon 1967, 210-11; Goodwin 1913, 59).

Judge Zane apparently viewed the statement as defiant and, saying that the defendant had declined to promise to obey the law, imposed the maximum sentence, a six-month prison term and a $300 fine (Cannon Transcript, 1885, 10).

Cannon recalled serving eight months in prison instead of six, the final two months voluntarily. The United States Supreme Court could not rule on his appeals until the following December, and his lawyers apparently felt he must remain in custody in order to force the court to rule on the merits instead of ducking the issue on mootness (A. Cannon 1905, 9).

The Cannon trial, conviction, and sentencing in April and May 1885 kept the Mormon community stirred up and angry. Editorials in the Deseret News thundered out almost daily with indignation, frustration, and at times a pro found sadness.

For example, on 6 May 1885, an editorial lamented the prosecutor’s use of a broad cohabitation definition which made convictions almost unavoidable and which was soon to be reviewed on appeal:

Reduced to a few words, the prosecution, in the case of Mr. Angus M. Cannon, take the ground that if a man dwells in the same habitation with two or more women whom he acknowledges to be his wives, he is guilty of unlawful cohabitation, as defined by the Edmunds Act, even if no sexual commerce has occurred. This is an entire change of base from that formerly maintained by Messrs. Dickson and [Charles S.] Varian [the United States Attorneys prosecuting the cases], who, in proceedings in former cases went to extraordinary and even grossly indecent lengths for the purpose of obtaining the very class of evidence they now assert is entirely immaterial. . . .

We are now enabled to state that Judge Zane performed that somersault desired by the prosecution (“New,” 1885).

A news item that same day recounted the trial court battles over the definition of the term “cohabitation” (“Trial,” 1885).

On 27 June 1885, the Utah Territorial Supreme Court affirmed Cannon’s conviction and sentence in all respects (United States v. Cannon, 1885). The lengthy opinion authored by Judge Jacob S. Boreman rejected each defense argument without summarizing trial testimony. In defining the crime of “cohabitation,” the court asked:

What, then, was the object of the congress in enacting this statute? It was, judging from the whole act, intended to be an aid in breaking up polygamy and the pretense thereof. The well-recognized difficulty of reaching the polygamy cases by reason of having to prove marriage, and by reason of the fact that the statute of limitations bars prosecutions after three years, no doubt led congress to pass this act. It was sought to break up the polygamic relation. It was necessary, in effect, to make polygamy a continuous offense, without requiring proof of marriage. Whether marriage took place or not, the pretense of marriage,—the living, to all intents and purposes, so far as the public could see, as husband and wife,—a holding out of that relationship to the world,—were the evils sought to be eradicated. . . . The appellant insists that cohabitation necessarily includes sexual intercourse, and that there can be no cohabitation without it. We find nothing whatever in the language or context to lead us to believe that congress meant to apply the statute to lewd and lascivious cohabitation, which would be the case if the construction contended for by the appellate were correct (pp. 374-75).

Chief Judge Zane concurred, as did Judge Orlando W. Powers, who filed a separate opinion stating

that the living and associating with two more more women as if married to all, tends to weaken the popular appreciation of true marriage, and this is detrimental to society. Therefore, for the purpose of protecting the marriage relation, the law under discussion was passed. It is directly aimed at the suppression of polygamy and the polygamous household as an evil example, dangerous in its tendency to the family relation as recognized by this nation (p. 382).

By September 1885, the First Presidency had directed Richards to try and negotiate a way out of the prosecutions. When that failed, they hoped for vindication from the Supreme Court. John Taylor and George Q. Cannon of the First Presidency wrote Richards on 11 September, saying: “We are greatly obliged to you for the kind and diligent interest you have taken in trying to bring about a settlement upon some fair basis of the lawsuit. We believe you have done all in your power to accomplish the objects we have had in view. We suppose now, that there is nothing left but to fight the suit through.”

Apparently Richards, now almost permanently stationed in Washington, D.C., tried to locate and retain former United States Senator George G. Vest to argue their cause before the Supreme Court (Taylor and Cannon to Richards 1885). Vest had been a senator from Missouri who debated against passage of the Edmunds Bill in 1882 (CHC 6:42; Buice n.d.). He had earlier represented Mormon interests before the Supreme Court in Murphy v. Ramsey (1885).

Vest was not secured for this case, however, and on 21 October 1885, Richards filed his brief before the Supreme Court. It was relatively short by modern standards, as was the brief of the federal government prepared by United States Attorney General A. H. Garland. Richards’ arguments were unsuccessful; in mid-December 1885, the Supreme Court of the United States affirmed the Utah Territorial Supreme Court in all respects (Cannon v. United States, 1885).

Justice Samuel Blatchford of New York, who had been appointed to the Court three years earlier by President Arthur, wrote for the majority. His opinion was joined by Chief Justice Morrison Waite who had authored the 1879 Reynolds opinion. Others in the majority were Justices Joseph P. Bradley, John M. Harlan, William B. Woods, Stanley Matthews, and Horace Gray.

Justices Samuel Miller and Stephen J. Field refused to join the majority. In a short opinion, they wrote that they would have overturned the conviction, requiring that sexual intercourse be an element of the crime. Miller and Field were the only justices on the court to have been appointed by President Abra ham Lincoln, who had maintained a fairly tolerant posture toward the Mormons (Arrington 1985, 295; Hubbard 1963; Larson 1965, 66-67).

Blatchford’s opinion recounts the history and language of various anti Mormon congressional acts (pp. 278-80), then summarizes what he saw as the critical trial testimony (pp. 281-84).

After listing the jury instructions objected to and advanced by Cannon at trial (pp. 284-86), Blatchford said the critical question was whether the crime of cohabitation under the statute required proof of sexual intercourse or not. The statute itself provided no definition, and Richards had argued in his brief that all contemporary statutory uses of the term did include sexual intercourse.

But we are of the opinion that this is not the proper interpretation of the statute; and that the [trial] Court properly charged the jury that the defendant was to be found guilty if he lived in the same house with the two women, and ate at their respective tables one-third of his time or thereabouts, and held them out to the world, by his language and conduct, or both, as his wives; and that it was not necessary it should be shown that he and the two women, or either of them, occupied the same bed or slept in the same room, or that he had sexual intercourse with either of them.

This interpretation is deductible from the language of the statute throughout. It refers wholly to the relations between men and women founded on the existence of actual marriages, or on the holding out of their existence (pp. 286-87).

Nowhere in the text of the opinion does Blatchford rely upon Reynolds, nor did Cannon’s lawyers ever inject a first amendment issue in their argument. Instead, Blatchford quoted at length from the Court’s March 1885 opinion in Murphy, which had affirmed other provisions of the Edmunds Act denying polygamous Mormons the right to vote. There the court defined polygamy in a way consistent with this definition of cohabitation.

On 12 December 1885 the Deseret News reported “The Verdict in the Cannon Case” and the full text of the opinion in the “Case of Angus M. Cannon, Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States.” An accompanying editorial cried indignantly that “There is one thing which we think will be made apparent to all who pay attention to passing events, and that is that the ‘moral’ crusade against the ‘Mormons’ has really nothing to do with morality” (“Moral,” 1885). The editorial further expressed outrage that sexual misconduct was not the vice being pursued by the Edmunds Act and local prosecutors.

The next day the Deseret News ran another editorial asking the question that no doubt troubled most Mormons in that day: “What Is Unlawful Cohabitation?”

The United States Supreme Court ruling in Cannon opened the prosecutorial floodgates. On 19 December 1885, four days after the formal filing of the decision, federal officers raided the little town of Parowan, arresting several women but missing most of the husbands they had sought to take into custody for cohabitation (“Doings,” 1885).

By the following year and leading right up to the Manifesto in 1890, court dockets were routinely congested with prosecutions of Mormons for polygamy, cohabitation, and after amendments to the law in 1887, for adultery, and in the instances of wives who lied on the witness stand rather than betray their husbands, perjury.

Congress was still not content and in 1887 engaged in more politically popular Mormon bashing with the enactment of the Tucker Amendment to the Edmunds Act (Ch. 397, 24 Stat. 635). The amendment further strengthened the hand of the federal prosecutors by expressly repealing the common law spousal immunity which enabled wives to refuse to testify as to marital communications with the husbands (Sec. 1); by allowing prosecutors to jail witnesses until a trial date if they suspected them to be uncooperative (Sec. 2); by adding the crimes of adultery, incest, and fornication to the prosecutors’ quiver (Sees. 3, 4, and 5); and by requiring an anti-polygamy oath of all jurors, office holders, and voters (Sec. 24). In a slap at the very women Congress claimed to be protecting, the amendment repealed suffrage, which had been awarded by the Utah Territorial Legislature in 1870 (Sec. 20). Future marriage ceremonies were also to be tightly regulated and recorded, with criminal penalties for failing to do so (Sec. 9).

Applying more financial pressure, Congress once again annulled the incorporation of the Church as a charitable entity (Sec. 17), this time adding the Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company for good measure (Sec. 15), and directed the attorney general to begin seizing and liquidating all Church holdings on behalf of the government (Sec. 13).

By 1889, 589 convictions had been obtained under the Edmunds-Tucker Act, according to a report from the attorney general to Congress (CHC 6:211). In July 1889, the district attorney for Utah Territory reported to the justice department that between 1885 and 1889 his office had obtained 970 convictions, while suffering 106 acquittals for violations of federal law in the territory. He also boasted of having collected $103,435.91 in fines and for feitures (“Number,” 1889). Church leaders would claim that by 1890, 1,300 Mormons had been imprisoned for offenses of this kind (CHC 6:211).

After the Cannon and Clawson decisions went against the Saints, the mood of the First Presidency turned from hopeful to bitter. “Those men [the Supreme Court] should be made to understand that we only submit to their infamies because they see us as powerless to resist them, and not because we are so dull, stupid and ignorant as not to know their are infamies,” wrote John Taylor and George Q. Cannon to Richards on 28 September 1886. The same letter brands the Supreme Court as “vindictive.”

The final blow for Mormon polygamy was the Supreme Court’s decision in The Late Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ v. United States (1890), which upheld the seizure of Church holdings by the federal government. Within a matter of weeks of that 19 May 1890 decision, President Wilford Woodruff issued the first Manifesto suspending the performance of new polygamous marriages (Godfrey 1970).

Today legal scholars and Mormon historians remain fascinated with Reynolds, writing a steady stream of articles on it and crediting the 1879 decision with the downfall of Mormon polygamy. In reality it was the Cannon decision six years later that resulted in the prosecution of hundreds of Mormon “cohabs,” encouraged anti-Mormon zealots to take up even more strident calls for the destruction of the social system of Zion, and eventually brought down that system. Only five years after the Cannon decision, the end came with the Manifesto.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue