Articles/Essays – Volume 21, No. 1

The Road to Dialogue: A Continuing Quest

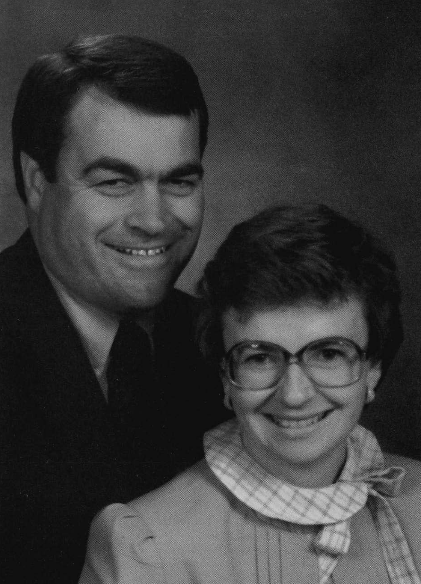

Once again the editorial mantle of DIALOGUE has passed to a new leadership. The journal is in excellent shape and bears a positive impact from each editorial team. For twenty years numerous individuals have tirelessly devoted talent, time, energy, and money to insure DIALOGUE’S creative success. Linda and Jack Newell and their board have bequeathed to us a journal that is intellectually exciting, literarily enticing, and financially stable. This journal’s success is based on a thorough and open commitment that is absolutely essential to the understanding of any and all things related to Mormons. We are most eager to continue the commitment and expand the journal’s role.

During the past few months, many colleagues have asked why we are willing to accept this challenging assignment. Other individuals have called or written and simply want to know who we are and why we were selected. Some close Church friends and certain family members are once again convinced that we are flirting with eternal disaster, if not outright damnation. We feel, as did our predecessors, that DIALOGUE readers need to know who we are and why this journal means so much to us.

In many respects, we, like DIALOGUE, were children of the 1960s. We were raised in Montpelier, Idaho, and like anyone there who desired higher education, we left after high school graduation. Kay went to Brigham Young University and Ross on a mission and then to Utah State University. As under graduates, we were confronted with the major national issues that engulfed domestic society. There is no doubt that John F. Kennedy’s idealistic call to service pressed us toward a career in higher education as we hoped to prepare young Americans for a role in reshaping the world.

After marriage, we moved to Washington State University where Ross began a Ph.D. program in American Studies. Kay worked, took care of infant son Bret, and took a class a semester. This was a typical, but somewhat regret table pattern, as it extended her bachelor’s degree from four to twenty-two years. While at WSU we became deeply concerned about civil rights and the Vietnam War, but Pullman is a long way from Montgomery or Berkeley. At the same time, we watched with great concern as some leaders and members of the Church flirted with radical right politics symbolized by the John Birch Society. We worried about conflict in faith and personal philosophy over the war, race relations, and many other aspects of Church life in the 1960s. We had great Church friends in Pullman, but we were too busy being students and parents to make social and political issues a part of the gospel.

In 1966, three of our former USU professors, Leonard Arrington, Stan Cazier, and Doug Alder, wrote to us about a new journal, DIALOGUE. It filled an immediate need and cut through minds that had become too dissertation specific and theologically indifferent. In that first issue, Karl Keller reminded us that any moral issue is a part of the gospel, and Richard Poll defined the breadth of belief within the Church. For us, this was an exciting beginning to a two-decade commitment to the journal and to the full scope of Mormon thought. Now in 1987, the journal deserves our continued support for the intellectual and spiritual reconciliation it conceived.

However, the volatile political issues did not go away. There is no doubt that 1968 was a pivotal year in our lives — a year of hope, despair, frustration, anger, anticipation, and for us, relocation. We had made up our minds about many things: Vietnam — bad; civil rights and Martin Luther King, Jr. — good; Lyndon Johnson — bad; Robert F. Kennedy — good; Frank Church — very good; John Birth Society — very bad; George Wallace — worse than very bad; and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints — only on Sunday. In recalling the difficulties of that year — the Tet offensive, Johnson’s quasi resignation, King’s assassination, Kennedy’s assassination, the disastrous Democratic convention, completion of a doctoral degree, the boycotted Olympics, and even Richard Nixon’s election — the two most traumatic events concerned the Church. We were emotionally scarred by George Wallace’s political rally in the Salt Lake Tabernacle and by the venomous language of hatred he spewed from behind the podium of the prophets. Second, during a temple recommend interview, Ross allowed himself to be backed into a corner over sustaining all the General Authorities. He raised a question about political statements and activities being out of the realm of Church leadership. After specifically refuting the political views of one apostle, he was both chastised and denied the recommend.

On the other hand, two great events of 1968 for us concerned the Church as well. After three years of being neighbors and friends, Bill and Judy Miller asked us to come back to Pullman when they were baptized. The Millers had lived above us in the old South Fairway married student apartments at Washington State University. Kay had befriended Judy the day they moved in, and as they progressed through school, we shared chores, duties, and more importantly, time.

Second, Ross accepted a teaching position at the University of Texas at Arlington, and we moved in August 1968. As we pulled a U-Haul to Arlington, we decided that we would have to be pretty quiet on matters of race and politics in order to survive in the Church in Texas. Three days later we met Otto and Wanda Puempel, and our ideas changed. Natives of Wisconsin, the Puempels had joined the Church after finishing medical school. Wanda’s mother and brother, recent converts, and two missionaries literally ambushed them when they came to visit in Missouri. Within two years, Otto was the bishop of the newly created Arlington Ward. He honestly knew very little about Church administration and organization, but he knew how to teach people as Christ taught. Wanda and Kay immediately tried to make the ward a social service agency. Ross and Jack Downey, another recent move-in and convert, joined Otto in one of the most unorthodox bishoprics ever created. Otto and Wanda were DIALOGUE Mormons, they just didn’t know it. When our Humphrey-Muskie bumper sticker was pulled off each Sunday in the Church parking lot, we simply replaced it. The Puempels stood by us through grape boycotts, anti-war moratoriums, and when Ross had to speak at a Kent State memorial service. More important, we all stood together on the issue of race relations.

We had concluded that the Church’s position on blacks and the priesthood was morally wrong, historically inaccurate, and scripturally untenable. When Steven G. Taggart published Mormonism’s Negro Policy: Social and Historical Origins (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1970) shortly before his untimely death from cancer, it confirmed our inner feelings. We had also decided that we could not ever help change people’s minds and hearts if we ourselves walked away from the problem. That is how we felt in the fall of 1969 when a tall, young black male student approached Ross after the first day of class and asked, “Are you a Mormon?” Thus began one of the most intense, beautiful, and ultimately tragic friendships of our lives. Curtis McLean possessed talent beyond measure and a soul of vast capacity. He wanted to know why he could not hold “our” priesthood. Ross successfully ducked the issue in front of other students and invited him to our home. It was painful to try to explain first why we did and then why we did not really believe it, and then how we could remain committed, active, and involved.

We invited him to sing in church, and he accepted. That had to be a great day in Texas Church history. Curtis arrived late and sat by Kay on the back row, unseen by the congregation. When Ross announced that Curtis McLean would sing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and he marched forward splendorously attired in a steel gray suit, black shirt, and white tie, the congregation could have received a mass tonsillectomy. Wanda played and Curtis sang. Later he played basketball with us, and we won the Arlington community church league as well as the local and regional LDS tournaments. We came to Salt Lake City to play in the all-Church tournament, but the high light of our trip was not basketball. It was Curtis standing at the foot of the Christus statue in the visitor’s center repeating simply, “My Lord, my Lord.” Curtis moved back to North Carolina at the end of the school year, and his words upon departing are forever embedded in our minds:

Someday, I will meet Jesus. And he will say,

“Curtis, were you good?”

“Yes, Jesus I was good.”

“Did you love everyone, Curtis?”

“Yes, Lord, I did.”

“Give me an example.”

“Lord, I spent 1969-70 with a bunch of racially prejudiced Mormons in Texas, and I love them with all my heart.”

We embraced and cried, and he got on the plane. Five years later we had lost contact.

We survived the sixties, and the Church survived us. Our perception of what we are and who we are and how we should treat others was molded dur ing those years in Texas. We felt at peace with ourselves and with the Church. Most important, we had added another son, Bart, to our family. In 1971, we accepted an offer to return to Utah State University. There our third son, Matthew, was born, Kay finally resumed her education in American Studies and Folklore, and Ross became a bishop and the chair of the History and Geography Department.

There is one other autobiographical note that we need to mention because it is such a part of who we are. In 1978, after four and a half years as bishop and three as a department chair, we received a teaching Fulbright to Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand. There we saw the Church in an entirely different light. The Porirua Ward was primarily Maori, and they taught us more about unconditional Christian love than we had ever experienced. From community to village, from the north to the south, we lived with and learned from these great people. It was exciting to watch cultural and religious differences reconciled within the teachings of Christ. It continues to enthrall us that a society based on communal sharing can really work. (They still haven’t put scoreboards in New Zealand gyms.) Most important, they taught us that the Church is different in different areas and that strength is derived from divergent solutions to personal problems. People were and are simply more important than programs.

How does this relate to our charge to lead DIALOGUE? We have always been convinced that institutional and personal progress comes from asking questions — specifically, why and why not? DIALOGUE has performed that role extremely well. We also feel that the Church is ultimately a “bottoms-up” organization. Ideas come from experience in the trenches and ultimately lead to Church-wide attempts at solutions. As the Church has grown and the bureaucracy and paid personnel expand, there is a real danger in the resulting standardization of administration and theology. For twenty years, DIALOGUE has maintained an openness that allows creative thinkers and writers to analyze and discuss significant issues.

As the Newells wrote in their first edited issue (Autumn 1982), DIALOGUE serves particular and specific purposes. It:

(1) offers reading material for Church members and others that goes beyond official publications;

(2) provides a forum for intellectual exploration of LDS Church history, theology and current practices;

(3) seeks to express creative thought for the enrichment of Mormon culture;

(4) nurtures a community of individuals who desire to shape their culture (pp. 9-12).

We would like to add that DIALOGUE continues to inspire many seekers. Many of us feel that questioning did not end with Joseph Smith and that we all share responsibility for our own destinies. Consequently, DIALOGUE provides an outlet for divergent views, new ideas, and different interpretations, as well as constant analysis of those in authority. The journal cannot be all things to all people, and its readership is minute compared to its potential. Its impact is significant, but more readers would make it greater. DIALOGUE has also paved the way for other journals, magazines, and newsletters. They have had a positive impact on the intellectual life within the Church, and we appreciate the relationship we share.

It is important to understand that DIALOGUE is independent. We are not tied to an institution or to a church or to a corporation. We, the subscribers and readers, are DIALOGUE. We will continue to seek financial support because we need to maintain the quality of the journal. Its unique format warrants continuation. All of our predecessors have set a positive course. They deserve applause and respect. There are things that might be of more interest to us, but thanks to the survey conducted, we are aware of what really appeals to our readers. We enjoy Mormon humor and folklore as well as the continuing discussion of authority versus individual free agency. Since the Church has existed longer in the twentieth century than the nineteenth, we will encourage more twentieth-century history and biography. We desperately desire more discussion of Christ and his teachings. There are many topics relative to the international church that demand exploration. The unique and gratifying personal essays remind all readers that each individual is significant and their experience has meaning for many. A continuing analysis of symbolism in all forms, social welfare issues, and missionary service is warranted. DIALOGUE also has a responsibility to uplift, and we encourage readers to examine each article closely and apply it personally because there is almost always something to foster both intellectual and spiritual growth. From this continued dialogue will come per sonal and ecclesiastical progress.

We need high quality submissions. We cannot sponsor the research or the creative writing. Authors must be willing to write, submit, handle temporary rejection, refine, resubmit, and finally achieve. We want to facilitate this process. The traditionally open editorial policy will not change. In order to address the issues of significance, we rely on our readers, so please continue your support. We are most happy that many of the volunteers who have helped the journal succeed in Utah are going to stay with DIALOGUE. This large and talented cadre of editors, proofreaders, typists, subscription solicitors, and volunteers have lent security to the journal.

Scholarship will promote faith. DIALOGUE will continue to encourage, cajole, foster, and publish the best essays, fiction, poetry, and history that relates to things Mormon. It is essential that we challenge, question, wonder, dream, and progress. The pages of DIALOGUE offer an opportunity for continued, thoughtful growth and objective analysis. We are ready to continue a rich heritage and are honored to have the opportunity to edit Dialogue. Already we have learned that great people will make the burden light. We ask for your support as we move forward with integrity, honesty, courage, faith, and love. Our editorial colleagues will allow us to do nothing less. The exciting and challenging opportunity is all of ours to share.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue