Articles/Essays – Volume 10, No. 4

The Spalding Theory Then and Now

But now a most singular & delicate subject presented itself for consideration. Seven young women we had on board, as passengers, to visit certain friends they had in Britain—Three of them were ladies of rank, and the rest were healthy bucksom Lasses.—Whilst deliberating on this subject a mariner arose whom we called droll Tom—Hark ye shipmates says he, Whilst tossed on the foming billows what brave son of neptune had any more regard for a woman than a sturgeon, but now we are all safely anchored on Terra firma—our sails furled & ship keeled up, I have a huge longing for some of those rosy dames—But willing to take my chance with my shipmates—I propose that they should make their choise of husbands. The plan was instantly adopted. As the chois [sic] fell on the young women they held a consultation on the subject. & in a short time made known the result— Droll Tom was rewarded for his benevolent proposal with one of the most sprightly rosy dames in the company.—Three other of the most cheerful resolute mariners were chosen by the other three buxhum Lasses—The three young Ladies fixed their choise on the Captain the mate & myself. The young Lady who chose me for a partner was possessed of every attractive charm both of body & mind—We united heart & hand with the fairest prospect of enjoying every delight & satisfaction which are attendant on the connubial State. Thus ended the affair. You may well conceive our singular situation. The six poor fellows who were doomed to live in a state of Cebicy [sic] or accept of savage dames, discovered a little chagrine & anxiety—However they consoled themselves with the idea of living in families where they could enjoy the company of the fair sex & be relieved from the work which belongs to the department of Women . . .

—Fabius, in “Manuscript Story”

And it came to pass that I, Nephi, took one of the daughters of Ishmael to wife; and also, my brethren took of the daughters of Ishmael to wife; and also Zoram took the eldest daughter of Ishmael to wife. And thus my father had fulfilled all the commandments of the Lord which had been given unto him. And also, I, Nephi, had been blessed of the Lord exceedingly. And it came to pass that the voice of the Lord spake unto my father by night, and commanded him that on the morrow he should take his journey into the wilderness . . .

—Nephi, in The Book of Mormon

Late in the summer of 1833 one Doctor Philastus Hurlbut, recently excommunicated from the Mormon church for “unchristianlike” conduct toward some of the sisters,[1] learned of a manuscript written some twenty years before by the late Reverend Solomon Spalding which was similar to the Book of Mormon. His interest piqued, he set out to investigate this story, principally through interviews with former residents of Conneaut, Ohio, where Spalding once had lived.

Hurlbut obtained remarkably similar affidavits from the Reverend Spalding’s brother John, John’s wife Martha and six other former neighbors and friends,[2] all of whom remembered that Spalding had written a “historical romance” about the “first settlers” of America. Entitled “Manuscript Found,” this novel “endeavored to show” that the American Indians were descendants of the Jews, or the lost tribes. John and Martha recalled that it “gave a detailed account of their journey from Jerusalem, by land and sea, till they arrived in America, under the command of NEPHI and LEHI. They afterwards had quarrels and contentions, and separated into two distinct nations, one of which he denominated Nephites and the other Lamanites. Cruel and bloody wars ensued, in which great multitudes were slain. They buried their dead in large heaps, which caused the mounds so common in this country.” Other Spalding acquaintances recalled that the story included characters named “Moroni” and “Laban,” and even a place called “Zarahemla.” The constant repetition of the phrases, “it came to pass” and “I, Nephi” seemed especially familiar.[3]

His appetite whetted by these statements, Hurlbut traced the manuscript to Otsego County, New York. There, he learned from Spalding’s widow—now Mrs. Davison (Spalding died in 1816)—the manuscript might be in a trunk in a friend’s home among some of Spalding’s other papers. On locating the chest in question, Hurlbut took what he supposed to be the original Manuscript Found.[4]

The storyline, as Hurlbut and his associates were shortly to discover, bore a superficial similarity to the Book of Mormon. While out for a walk one day, Spalding wrote in his introduction, he “hapned [sic] to tread on a flat Stone” engraved with a badly worn inscription. “With the assistance of a leaver I raised the Stone . . . [and discovered] that it was designed as a cover to an artificial cave.” Descending to the bottom, he found “a big flat Stone fixed in the form of a doar [sic].” On tearing down the door, he discovered an earthen box within which were “eight sheets of parchment.” Written on the sheets “in an eligant hand with Roman Letters & in the Latin Language” was “a history of the authors [sic] life & that part of America which extends along the great Lakes & the waters of the Mississippy.” The history which followed, explained Spalding, was a summary translation of this Roman account.[5]

Although there are unmistakable parallels in Spalding’s introduction and Joseph Smith’s early experiences,[6] there is little to compare in the actual narrative histories. Spalding wrote of a group of Romans living about the time of Constantine, who had been blown off course on a voyage to “Brittain.” Through the “tender mercies of their God,” they safely reached the east coast of North America, where one of their number, Fabius, began writing a history of their experiences. Most of Fabius’ account deals with the Deli wan, Kentuck and Sciotan Indians. Aside from an emphasis on wars, however, there are virtually no similarities in episodes, characters, or themes between Spalding’s account and what was found in the Book of Mormon. Only one brief passage is notably reminiscent of the Book of Mormon: one of Spalding’s characters, Hamack, had “a stone which he pronounced transparent—tho’ it was not trans parent to common eyes. Thro’ this he could view things present & things to come. Could behold the dark intrigues & cabals of foreign courts, & discover hidden treasures, secluded from the eyes of other mortals.”[7]

The narrative style is particularly dissimilar, and Spalding’s story contains not a single “it came to pass.” As to the specific names recalled by those Hurlbut interviewed, Spalding had written of neither a Nephi, Lehi, Laman, Moroni, nor a Zarahemla. Stretching credulity (but being charitable to faded memories), one can find some similarity to a handful of Book of Mormon names. There was a “Moonrod” (cf. Moroni); a “Mammoon” (cf. Mormon), the native term for a domesticated woolley mammoth; a “Lamesa” (cf. Laman), in this case a woman; a “Hamelick” (cf. Ameleki or Amelickiah), and a couple of additional Book of Mormon “sounding” names, “Hadoram” and “Boakim.” More commonly Spalding used names (such as Bombal, Chianga, Hamboon, Lobasko, and Ulipoon) with no resemblance whatsoever to those of Joseph Smith.[8]

The materials collected by Hurlbut, including the affidavits and the Spalding manuscript, were sold shortly thereafter to Eber D. Howe, who in 1834 published what B. H. Roberts termed the first anti-Mormon work “of any pretentions.” The final chapter of Howe’s book, Mormonism Unvailed [sic], set forth at length the “Spalding theory” of the origin of the Book of Mormon. It had been evident, Howe wrote (although Mormons were convinced that Hurlbut was actually the author), “from the beginning of the imposture” that “a more talented knave [than Joseph Smith was] behind the curtain.” The ultimate source, he proposed, was the Reverend Solomon Spalding, literate graduate of Dartmouth College. In support of this thesis were placed the eight striking statements collected by Hurlbut. A passing reference was made to the manuscript obtained by Hurlbut from the Spalding trunk to indicate that it had not proved to be a copy of Manuscript Found. Rather, it was “a fabulous account of a ship’s being driven upon the American coast, while proceeding from Rome to Britain.” When this latter manuscript was shown to several of those previously interviewed by Hurlbut, they reportedly recognized it as Spalding’s work, but said that it bore “no resemblance” to the Manuscript Found. Spalding, according to Howe, had “told them that he had altered his first plan of writing, by going further back with dates, and writing in the old scripture style.[9]

Howe’s casual dismissal of the Spalding manuscript located by Hurlbut was merely the first of many selective presentations of the relevant facts. Much of what Hurlbut’s eight witnesses remembered could well have been based on the story found in the trunk. Although not apparent in Howe’s brief summary, that story was indeed about a “manuscript found,” and recounts the “arts, sciences, customs and laws,” and particularly the wars of ancient inhabitants of America. Moreover, it purports to be based—as one of Hurlbut’s sources had recalled—on a translation of some records “buried in the earth, or in a cave.” The claim that Spalding’s work was interesting listening—one witness even spoke of “humorous passages”—is hard to reconcile with either the Book of Mormon or the Roman story. The text of the latter at least gives occasional evidence of trying to be amusing. None of the foregoing parallels was central to the plagiarism argument, of course, but a detailed knowledge of the manuscript located by Hurlbut should have focussed more careful attention on claims uniquely related to the Book of Mormon.

The Hurlbut-Howe case for plagiarism rested primarily on two such unique claims—the assertions that “most” of the names and the “leading incidents” in the Book of Mormon originated with Solomon Spalding. Actually this sweeping generalization rested on less than a dozen disingenuously uniform bits of evidence. For example, in a sentence of virtually identical wording, the majority of Hurlbut’s witnesses cited Spalding’s alleged account of the departure of a small group of Jews from Jerusalem, and “their journey, by land and sea, till they arrived in America.” Many also recalled that the emigrants were descendants of the “lost tribes”—at the time a common explanation of Indian origins, but without support in either the Book of Mormon or the Roman story. One of Hurlbut’s sources recalled the group landing near the “Straits of Darien” (now Panama), reflecting an early interpretation of Book of Mormon geography shared by Eber D. Howe, among others. (Joseph Smith reportedly placed the landing near Valparaiso, Chile.)[10]

The most striking aspect of the early claims unquestionably related to the proper names. Here, however, the coincidence of memory was even more suspect. Of some 300 potential names, Hurlbut’s witnesses all used the same handful of specific examples. Most cited “Nephi” and “Lehi.” Two witnesses (John and Martha Spalding) added “Nephites” and “Lamanites,” and only three additional names were mentioned even once—”Laban,” “Zarahemla” and “Moroni.” (The last two by the witness who remembered the humorous passages). Despite the elapsed decades, all recalled identical spellings for these odd-sounding names, spellings which matched exactly those found in the Book of Mormon. A corollary claim that Spalding wrote in a “scripture style” was illustrated with the same unanimity. Everyone who recalled specific wording cited “and it came to pass,” with “now it came to pass” a distant second. Not surprisingly, nearly everyone acknowledged that his memory had been refreshed by a recent reading of the Book of Mormon.

Joseph Smith’s access to the Manuscript Found was not as well documented as the plagiarism itself. Spalding’s widow, Mrs. Davison, reportedly told Hurlbut that on moving to Pittsburg, “she thinks” her husband took his manuscript to the printing office of Lambdin & Patterson. She was “quite uncertain” if it had been returned. Howe added, “We have been credibly informed that [Sidney Rigdon] was on terms of intimacy with Lambdin” and “was frequently in his shop.” Lambdin, Howe surmised, gave the manuscript to Rigdon sometime between 1823 and 1824, during which time Rigdon lived in Pittsburg. Rigdon, in turn, assisted Joseph Smith in expanding Spalding’s secular historical piece into the Book of Mormon. Howe had been unable to establish this connection conclusively for Lambdin was dead (having died in 1825), and Patterson had “no recollection of any such manuscript.” It was unlikely, however, that Patterson would have seen it, since during the time of Spalding’s residence in Pittsburg (about 1812-1814), “the business of printing was conducted wholly by Lambdin.” Patterson reportedly recalled manuscripts remaining on the shelf for years, “without being printed or even examined.” Howe, in concluding, felt confident in holding “out Sidney Rigdon to the world as .. . the original ‘author and proprietor’ of the whole Mormon conspiracy. . . ,”[11] The lapses in documentation were, it seems, not that important in the face of the substantial evidence already presented.

Initially the publication of Mormonism Unvailed appears not to have been a major concern to the Mormons. By 1838, however, Apostle Parley Pratt found that “certain religious papers”[12] in New York were advancing the Spalding theory as “positive, certain, and not to be disputed.” He therefore included a brief denunciation in a short work entitled Mormonism Unveiled [sic] (1838), limited principally to a denial of Rigdon’s early involvement with the manuscript, and an attack on the motives and character of Philastus Hurlbut.[13] Subsequent exchanges between Mormons and their antagonists regularly included increasingly lengthy sections on the Spalding theory, which by the early 1840’s became the accepted explanation of the origin of the Book of Mormon.

“The Relic of Solomon Spalding”

For the next half-century Spalding advocates continued to turn up new but increasingly elderly “living witnesses” to support their case. Perhaps the most significant addition to the evidence came with the publication in 1839 of a statement purportedly written by Spalding’s 70-year-old widow. Her statement, which was included in an article by the Reverend John Storrs appearing in a May issue of the Boston Recorder, enlarged considerably on the brief comment attributed to her in Mormonism Unvailed. Mrs. Davison now stated that Patterson had been enthusiastic about her husband’s novel, even recommending that he write a title page and preface. Spalding, for reasons unknown, failed to do so and at length received back his manuscript. She also alleged that Sidney Rigdon “was at that time connected with the printing office of Mr. Patterson” (“as Rigdon himself has frequently stated”), and had ample opportunity” to copy her husband’s manuscript. Although in 1834 Howe had written that Mrs. Davison had “no distinct knowledge” of the content of the manuscript, she now remembered that it was written “in the most ancient style,” imitating “as nearly as possible” the Old Testament. As to the fate of the original manuscript, she had carefully preserved it following her husband’s death in 1816, and it “frequently” had been examined by her daughter.[14]

The Mormons almost immediately imputed to “Priest Storrs” much the same role they felt previously had been played by Philastus Hurlbut—a molder rather than collector of relevant testimony, and the new Davison statement elicited a more vigorous response than had Mormonism Unvailed. Sidney Rigdon sent an impassioned denial to the Boston Journal, much of which was devoted to impeaching in detail the moral character of Philastus Hurlbut (as well as his wife). He hotly denied any knowledge of Spalding or “his hopeful wife.”[15] While he did have a “very slight acquaintance” with Patterson during his residence in Pittsburg (1822-1826), Patterson was not in the printing business during that time (nor, so far as he knew, at any earlier time). Why, Rigdon wrote, hadn’t someone sought the testimony of Patterson directly? “He would testify to what I have said.” Parley Pratt also penned an indignant letter, this one to the editor of the New York Era, one of many papers which had reprinted Storrs’ Journal article. He, as well, denied that Rigdon had any connection with Patterson, the latter’s printing establishment, the writing of the Book of Mormon—or, for that matter, the organization of the Church itself (Pratt having baptized Rigdon in October 1830). He was particularly sensitive to an impression, implicit in Mrs. Davison’s statement, that Hurlbut had in fact obtained the implicated manuscript: “. . . if there is such a manuscript in existence, let it come forward at once. . . .”[16]

At the very least, the language and style of Mrs. Davison’s statement did seem inconsistent with both her age and previous limitation of memory. Even some Spalding proponents later acknowledged the suspiciously “argumentative style and failure to distinquish between personal knowledge and argumentative inference.”[17] It was to be over a century before a non-Mormon would finally wonder in print if Hurlbut himself had not co-authored at least a portion of the statements he collected. That the Reverend John Storrs did not fare quite so well is due largely to the efforts of Mr. Jesse Haven. Haven, who apparently was a Mormon, sought out and interviewed both Mrs. Davison and the daughter with whom she now lived, Mrs. Matilda Spalding McKinstry. A reconstruction of this interview was published in the Quincy Whig. While “in the main” Mrs. Davison believed that what was published in Storr’s article over her name was “true,” she had not written the account, nor had she signed it or even seen it before publication. A Mr. Austin had interviewed her and then sent the notes to Storrs.

Even in the Haven interview, however, Mrs. Davison added something new, as she for the first time claimed to recall something of the Spalding text. She had now read the Book of Mormon, she said, and thought “some few of the names are alike” to those in her husband’s work. The Manuscript Found, however, was only about “one-third as large” as the Book of Mormon, and concerned an “idolatrous” rather than a religious people. She also recalled that shortly after Hurlbut had taken the manuscript from her trunk (to publish it, he said), he wrote to say that the manuscript did not read as expected and was not going to be published. Mrs. Mckinstry, the daughter, added that she, too, had read the Manuscript Found, when about twelve years old (this would be 1818, about two years after Spalding’s death). Although not certain, she also thought that some of the names agreed with those in the Book of Mormon, which she acknowledged she had not read.[18] Some forty years later, Mrs. McKinstry would be interviewed again and, like her mother, demonstrate an enlargement of memory. That both simply did not recall any details of Spalding’s story—as they initially stated—is supported circumstantially by the apparent failure of either to recognize Howe’s accurate summary of the Roman story, the one indisputable Spalding novel.

A defense of what the Mormons quickly termed the Reverend Storr’s “cunning deception” was not long in coming. In a chapter entitled “Mormon Jesuitism,” the Reverend John A. Clark (Gleanings By the Way, 1842) reprinted letters solicited from both Storrs and Austin. Mrs. Davison, explained Austin, was “aged” and “very infirm” at the time of the interview, but had indeed signed “a statement of facts contained in that [published] letter” (which signed paper he still possessed). To this Storrs added that in view of Mrs. Davison’s confirmation of the accuracy of the account, Mormon objections to his literary license were mere “quibbling.”[19] Regarding the fate of Spalding’s original manuscript—a point of considerable importance in later years—Mrs. Davison was said to have had “not the least doubt” that Hurlbut found it in the trunk where she had stored it. As the trunk was now known to be empty, Mrs. Davison was sure that Hurlbut had sold it to the Mormons. She was joined in this view by Storrs, Austin and Clark; Austin even reported the price—$400.[20]

The most extensive Mormon response to the Hurlbut and Storrs accounts was a short book published in 1840 by Benjamin Winchester on The Orgin of the Spaulding Theory (Philadelphia, and republished the following year in Liverpool). Winchester’s approach, a lengthy restatement of the variously published Mormon arguments to date, was followed by nearly all Mormon apologists thereafter. He began with an extensive attack on Philastus Hurlbut, portraying him as both a “fabricator” and “confirmed drunkard,” who after being “reduced to beggary” fled the country to escape a charge of theft. His disreputable background included “adultery” and a threat on the life of Joseph Smith “for which he was bound over in the sum of five hundred dollars, to keep the peace.”[21]

Winchester followed his discussion of Hurlbut with a lengthy biographical sketch of Sidney Rigdon, designed to demonstrate the improbability of his involvement in the scheme, and also included a reprint of Jesse Haven’s interview with Mrs. Davison. Little effort was expended on analyzing or refuting directly the Hurlbut or Storrs-Davison statements, beyond enumerating a number of internal inconsistencies. Rather, Winchester—and those who followed him—relied principally on establishing three basic points: Rigdon had not arrived in Pittsburg until about 1822, well after Spalding had retrieved his manuscript; after 1816 the manuscript remained with Spalding’s widow until about 1833 when Hurlbut obtained it from the trunk; Hurlbut found, on reading the manuscript, that it did not match the Book of Mormon. Thus, there never had been a credible case in the first place.

Although Winchester’s documentation and analysis were no more rigorous than those published previously he did contribute summaries of two new testimonies. In the first, a Mr. Jackson, allegedly a former neighbor of Spalding, denied any similarity between Spalding’s Manuscript Found and the Book of Mormon. He had read both, he reportedly said, and the former was about a group of Romans.[22] Unfortunately Jackson’s memory did not extend beyond the synopsis already published by Howe in Mormonism Unvailed. Winchester’s second new item was a one sentence summary of an interview between a Mr. Green and Patterson, in which the Pittsburg printer reportedly again denied (as Howe previously had written) any knowledge of the Spalding manuscript.[23]

The Thick Plottens

The opinion of Patterson was central to the claims of both sides. Rigdon believed Patterson would vindicate him, and both Winchester and Howe wrote that Patterson denied any knowledge of the Spalding manuscript. Mrs. Davison, on the other hand, allegedly remembered Patterson responding positively to her husband’s manuscript. In 1842, Patterson himself finally provided a cautiously worded statement on the subject. As he recalled it, “a gentleman, originally from the east, had put into his [assistant’s] hands a manuscript of a singular work, chiefly in the style of our English translation of the Bible, … ” Patterson had “only read a few pages” of the work, and “finding nothing apparently exceptionable” about it, agreed “he might publish it if the author furnished the funds.” No funds were forthcoming, so after “some weeks,” the manuscript, “as I supposed at the time,” was returned to the author.[24]

Apparently this was Patterson’s sole published statement. His son Robert, investigating the Spalding theory some forty years later, added nothing new from his father, even relying on a secondary source for the foregoing quotation (the senior Patterson died in 1854).[25] The younger Patterson, however, was able to add some relevant background material. Lambdin, who was implicated in Mormonism Unvailed as Rigdon’s source, had joined Patterson’s firm in 1812, at the age of 14, but did not become a partner (“Patterson & Lambdin”) until 1818. He died, as Howe had stated, about 1825. Robert Patterson eventually contacted Lambdin’s widow (in 1879), and she denied knowledge of Rigdon, who “certainly could not have been friends with Mr. Lambdin.” He also located a former employee of Patterson & Lambdin, who had worked with the firm from 1818 to 1820, but who had no recollection of either Spalding or Rigdon. The younger Patterson, who accepted Rigdon’s role as the instrument in conveying Spalding’s story to Joseph Smith, also sought out both Hurlbut and Howe for an explanation of their misstatements on Patterson & Lambdin. Howe attributed the information to Hurlbut, who in turn denied ever having spoken with Patterson in the first place![26]

Conflicting reports about Rigdon’s access to the manuscript proved no obstacle to the early acceptance of the basic Spalding theory. Its real strength lay in the unquestioned assertions that essential elements of the Book of Mormon were identical to Spalding’s romance. Any lingering doubt about the acceptability of the Hurlbut-Howe thesis was put to rest in 1842 by the publication of no fewer than six works on the Mormons—all expounding the Spalding theory.[27] Some, such as Daniel Kidder’s Mormonism and the Mormons, stayed strictly with the original thesis, for the most part simply extracting text verbatim from Mormonism Unvailed. Others, such as the Reverend John Clark, in Gleanings By the Way, were willing to acknowledge that there were significant questions about Rigdon’s involvement. On reflection, Clark did not find this to be a problem: Someone with earlier access to Spalding’s manuscript could have made a copy which Rigdon obtained on moving to Pittsburg in 1822; or, perhaps Rigdon had not been involved at all, in which case Smith himself must have obtained the manuscript “some way or other.”[28] The Reverend J. B. Turner, also acknowledging a Rigdon problem, offered a more specific solution in his Mormonism in All Ages (1842). Joseph Smith probably had obtained the manuscript directly from the chest where it had been stored in New York; he had, after all, been seen “loitering about these regions” for some four years after working nearby for Josiah Stowell in 1823.[29] This explanation had special appeal to Turner, who could “not imagine a man of Rigdon’s talent, power of language, and knowledge of the Bible, ever could have jumbled together such a bundle of absurdities. … ” His conclusion was almost exactly the opposite of a key assumption of Hurlbut and Howe:

Whoever got the Spaulding manuscript, Joe Smith, and Joe alone, is sole ‘author and proprietor’ of its offspring, the Book of Mormon. There is not, probably, another man on the globe that could write such a book . . . and he would not have done it had not some materials been furnished to his hand to suggest the outline of the story.[30]

Mormon John E. Page responded to the now unanimous acclaim of the Hurlbut-Howe thesis with a small book of his own, The Spaulding Story . . ., published in 1843.[31] While relying primarily on lengthy quotations from the statements previously published, he also added several new testimonies, directed primarily at the weak Rigdon link. Benjamin Winchester, in his earlier defense of the Mormon position, stated that Rigdon’s mother told him “before the Spaulding theory was ever thought of” that Sidney had “lived at home, and worked on the farm, until the twenty-sixth year of his age [1819].”[32] To this, John Page now added an affidavit from older brother Carvil Rigdon and brother-in-law Peter Boyer to the same effect. Sidney had lived on his father’s farm until 1818 or 1819 when he left to study with a Baptist minister in Beaver County, Pennsylvania. From there he moved to Ohio, finally “returning” to Pittsburg (the Rigdon farm was about 15 miles outside of the city) in the winter of 1821-22 to preach at the “First Regular Baptist Church.”[33] Boyer, who for a short while was a Mormon, was questioned further on this point many years later, but “positively affirmed” that Rigdon never lived in Pittsburg prior to 1822, adding that “they were boys together and he ought to know.”[34]

Page also quoted the Rev. John Rigdon—apparently Sidney’s uncle or brother—as saying he had known Sidney “on the greatest terms of intimacy” “from his infancy till after the publication of said Book of Mormon,” and that he did not believe he “had anything whatever to do with it.”[35] Finally, Page published a letter written two years before by Mormon apostle, Orson Hyde. Hyde wrote that before becoming a Mormon he had been a student of Sidney Rigdon in the Christian Baptist Church. He had known Rigdon “intimately” over “a number of years,” and resided in his home in 1829. Hyde was sure that were Rigdon guilty of the schemes laid to him, some hint of his involvement would have been apparent, but there had been no such intimation “in any shape or manner.”[36] Furthermore, Hyde wrote, in 1832 he had preached in New Salem (formerly Conneaut) “and baptized many of Mr. Spaulding’s old neighbors, but they never intimated to me that there was any similarity between the Book of Mormon and Mr. Spaulding’s romance.” After Hurlbut “brought forth the idea,” Hyde returned to New Salem and made inquiries of the neighbors. “They said that Mr. Spaulding wrote a book, and that they frequently heard him read the manuscript: but that any one should say that it was like the Book of Mormon, was most surprising, and must be the last pitiful resort that the devil had.”[37]

Not unexpectedly, the outcome of the debate—despite the efforts of Haven, Hyde, Winchester and Page—was never in doubt: the Book of Mormon was a plagiarism. During the decades after the unanimous verdict of 1842, only one lost non-Mormon voice advanced a distinctly contrary view. Orsamus Turner, in a local history of western New York published in 1851, wrote that “those who were best acquainted with the Smith family” believed there was “no foundation to the Spaulding story.” The Book of Mormon “without doubt [was] a production of the Smith family, aided by Oliver Cowdery.”[38] Over whelmingly, however, later writers on Mormonism simply extracted or restated sections from Howe’s Mormonism Unvailed, Storr’s Davison statement, Clark’s Gleanings, or later, tertiary works. Admittedly, there was uncertainty as to the means by which the plagiarism had been effected, but unraveling the “how” of the fraud was necessary only to satisfy “public curiosity.”[39]

Although inconsistencies in the published testimonies did not lead to fundamental questions about the validity of the reported accounts, they did spawn a remarkable variety of postulates as to how the deed might have been done.[40] Mid-century discussions, however, contributed more to the original Hurlbut-Howe thesis than an increasingly convoluted analysis. While it was to be many years before new “primary” source material was published, the evidence still managed to grow more convincing by the decade.[41] Perhaps the most egregious addition to the traditional story appeared in the New American Cyclopedia, which informed its readership that “as early as 1813 this work [of Spalding] was announced in the newspapers as forthcoming, and as containing a translation of the ‘Book of Mormon.'”[42]

Another example of the new “evidence” added to the theory at mid-century, not strictly speaking in the same category as the foregoing, was found in Pomeroy Tucker’s Origin, Rise, and Progress of Mormonism (1867). Tucker, former editor of the Wayne Sentinel (Palmyra, New York) and distant neighbor of the Smith family, carried the Rigdon connection one step further than previous writers. Notwithstanding an error-filled reconstruction of the early Spalding story, his new information on Rigdon was readily accepted by non-Mormon authors. Tucker recalled a “mysterious stranger” visiting the Smith home twice between 1827 and 1830—in his mind, none other than Sidney Rigdon. This appears to be the first published attempt to “document” a pre-1830 link between Rigdon and Smith, a consideration previously ignored and probably felt by most to be unnecessary.[43]

New Life and New Light

The 1880’s, a high point in national anti-Mormon activity, saw a resurgence of interest in the Spalding theory unprecedented since its original introduction. This was at first due to the independent efforts of the Reverend Robert Patterson (son of the printer) and Ellen Dickinson (grandniece of Solomon Spalding) to resolve some of the lingering questions. Between them they collected, both from published sources and directly, some twenty to thirty new testimonies. These materials were shortly published in Patterson’s Who Wrote the Book of Mormon? (1882) and Dickinson’s New Light on Mormonism (1885), and it was in large part because of this new “evidence” that the Spalding theory survived the discovery in 1884 of a long lost Solomon Spalding manuscript.

Although the most significant of the newly collected statements came from Mrs. McKinstry, Spalding’s now elderly daughter, there were important inter views with Philastus Hurlbut and Eber D. Howe—both now in their eighties. Several new “living witnesses” to the “identity” of the Book of Mormon and Manuscript Found were also located, as was Mrs. Lambdin (wife of Rigdon’s alleged accomplice). Dickinson and Patterson published a few interviews with several older residents of Pittsburg, some of whom claimed early knowledge of Patterson & Lambdin, and a handful of second-hand accounts relating to Sidney Rigdon’s early activities. Buried in Mrs. Dickinson’s appendix—and dismissed by her—was a letter from one W. H. Rice, dated August 1885, who wrote that his father recently had located “an original manuscript from the pen of Solomon Spaulding.” It had been marked “Conneaut Story,” and was written in “Scripture narrative style”, similar but “not identical . . . in any part to the Book of Mormon.”[44]

The new McKinstry statement was first published in Scribner’s Monthly in August 1880. Now in her mid-seventies, Mrs. McKinstry nonetheless displayed a more vivid memory than was apparent in her brief interview some forty years earlier. Where before she had seemed uncertain about the names in the Spalding manuscript, now they were “as fresh to me . . . as though I heard them yesterday . . . ‘Mormon,’ ‘Maroni,’ ‘Lamenite,’ ‘Nephi.’ ” Patterson, she also remembered, had been an “intimate friend” of her father (in contrast to Patterson’s vaguely worded recollection of a “gentleman, originally from the east”), and she and her father had frequently visited his library. Her mother told her that Patterson had recommended that her father “polish” up his manuscript; “finish it, and you will make money out of it.”

Mrs. McKinstry had seen the manuscript when she was eleven years old (about 1817). It was about “an inch thick,” and stored in the trunk with some other papers. While “she did not read it,” she had “looked through it and had it in my hands many times, and saw the names I had heard at Conneaut, when my father read it to his friends.” She credited her mother with saying that the manuscript was written “in biblical style.”[45]

Two years later, W. H. Kelley of the Reorganized Church asked Mrs. McKinstry how she had first come to notice the similarity of names. She reportedly replied that her “attention was first called to it by some parties who asked me if I did not remember it, and then I remembered that they were [alike].” “Mr. Spaulding had a way of making a very fancy capital letter at the beginning of a chapter and I remembered the name Lehi, I think it was, from its being written that way.”[46]

Ann Redfield also was consulted by Ellen Dickinson in 1880. She too had been in the Spalding home, about 1818, as a boarder. She had not read the manuscript herself, she reported, but she had heard enough about it from the family to “at once recognize the resemblance between it” and the Book of Mormon when the latter appeared some years later. In addition, Redfield asserted, Mrs. Davison sometime before 1828 had expressed the belief that Sidney Rigdon had copied her husband’s manuscript![47] (All this despite Mrs. Davison’s apparent failure, when first interviewed in 1833, either to implicate Rigdon or to recall details of the Spalding text.) Early suspicion of Rigdon by the Spalding family was alleged by several other late witnesses, who purported as well to have some knowledge of the text of Spalding’s Manuscript Found.[48]

To exponents of the Spalding theory (i.e., virtually everyone but the Mormons), the case for plagiarism was now stronger than ever. Unfortunately, however, pieces with no apparent place in the puzzle continued to turn up. In 1880 Ellen Dickinson learned that George Clark’s wife had been shown the Spalding manuscript as late as 1831. It was in Clark’s home that the Spalding trunk was stored, and there that Hurlbut found his manuscript. Clark recounted that his wife—then his fiancee—was given the manuscript by Mrs. Spalding when both had been staying in the Clark home. She found it “dry reading” and returned the manuscript after reading only “a few pages.” In response to a specific question from Dickinson, Mrs. Clark denied any memory of the contents, nor had she any recollection of the names “Maroni” or “Mormon.”[49]

Not surprisingly, in light of the accumulated evidence, the Spalding family was convinced that Philastus Hurlbut had indeed taken the original Manuscript Found from the trunk. Dickinson, in pursuing this point, sought out and interviewed both Hurlbut and Howe. Despite her efforts to obtain a confession from Hurlbut, she was unable to shake his original testimony. He had found a manuscript in the trunk and given it to Howe. The story it contained did not match the Book of Mormon, but rather—as stated in Mormonism Unvailed—recounted the adventures of some Romans. Howe had apparently misplaced the manuscript, and he assumed it later was destroyed in a fire.[50]

As Dickinson reconstructed her later interview with Howe, she was able lo provoke him into speculating that Hurlbut might have found two manuscripts in the chest.[51] It is clear, however, from a letter written by Howe just a few months before, that he accepted Hurlbut’s account of a single Spalding manuscript in the trunk.[52] Unsatisfied, Mrs. Dickinson could only offer her readers an affidavit from “O. E. Kellogg,” who had accompanied her to see Hurlbut: “We carefully listened to every word said, and watched Mr. Hurlbut’s countenance and arrived at the same conclusion—that Hurlbut knows more than he told.”[53]

In general, efforts to implicate Rigdon were about as successful in the 1880’s as they had been previously.[54] Unable to locate a source who would claim first-hand knowledge of Rigdon’s employment with Patterson, Mrs. Dickinson and the younger Patterson turned instead to second-hand accounts of several “unimpeachable” witnesses. George M. French, for example, “now in his eighty-third year,” retained a “vivid impression” of a conversation he had some fifty years earlier with the Rev. Cephas Dodd, a physician who attended Spalding’s last illness. Dodd had expressed his “positive belief” that “Rigdon was the agent in transforming Spaulding’s manuscript into the Book of Mormon.” French dated the conversation with Dodd to 1832, a year before the original Hurlbut interviews; Dodd’s suspicion must therefore have been derived from Spalding himself![55] Equally solid was the testimony of the Rev. A. G. Kirk, who recalled a conversation a decade before (about 1870) in which the Rev. John Winter recounted a visit over fifty years earlier to Sidney Ridgon’s study, in 1822-23. During the visit, Rigdon allegedly had taken a large manuscript from his desk, and said “in substance,” “. . . Spau’ding . . . brought this to the printer to see if it would pay to publish it. It is a romance of the Bible.”[56]

Additional testimony, if no less credible, was generally a little less specific. The statements of three early ministers were located, all attesting to Rigdon’s knowledge of the Book of Mormon well before its publication. Two of these were Alexander Campbell, whose movement Rigdon had left to become a Mormon, and Adamson Bentley, Rigdon’s brother-in-law (their wives were sisters). Bentley, “whose testimony is beyond the imputation of doubt or suspicion,” had written in 1841 of a conversation he had with Sidney about 1828. A book was “coming out,” Rigdon allegedly said, “the manuscript of which had been found engraved on gold plates.”[57] No mention was made of the long-standing antipathy between Rigdon and the purportedly impartial Bentley, dating back at least six years before Bentley’s statement. By Rigdon’s account at least, the Rev. Bentley had convinced his father-in-law to exclude Ridgon’s wife from her family inheritance (before 1836).[58] Bentley’s statement was supported by Alexander Campbell, who claimed in 1841 to have been present during the alleged Bentley-Rigdon conversation.[59] Conveniently omit ted, however, is any reference to Campbell’s earlier view, published in 1831 ascribing total responsibility for the Book of Mormon to Joseph Smith.[60] The paradox becomes less confusing when one learns that Campbell changed his mind about the authorship of the Book of Mormon after reading Howe’s Mormonism Unvailed.[61] The testimony of the third of this group of ministers, while coming much later, is probably related to the previous two. Campbellite Reverend D. Atwater, “a man noted for his strict regard for truth and justice,” wrote in 1873 that he could still remember hearing as a youth a conversation between Rigdon and his father along the same lines as that recounted by Bentley and Campbell. He was sure it had been before 1830.[62] One presumes that either father or son Atwater was the “Darwin Atwater” characterized by Rigdon in 1836 as having “a great deal of labor to carry about and read Howe’s book.”[63] The remaining new testimonies were, if possible, less impressive still.[64]

Conspicuously absent from the ostensibly exhaustive surveys of Patterson and Dickinson was any later statement by Sidney Rigdon, or any reference whatever to Oliver Cowdery. Rigdon, after a turbulent thirteen years with the Mormons, had been excommunicated in 1844. He moved to Pittsburg and attempted to establish his own branch of the church, but this soon failed. The remainder of his life was one of complete alienation from the Mormon community. Nonetheless, he continued till his death in 1876 to deny vigorously any knowledge of the Spalding manuscript, or collusion with Joseph Smith in the preparation of the Book of Mormon.[65] Oliver Cowdery, as Joseph Smith’s principal scribe in the preparation of the Book of Mormon, should have been an invaluable source as well—particularly since he too had been excommunicated from the church, in 1838. But, like Rigdon, Cowdery also denied throughout his life any charge of fraud in the writing of the Book of Mormon.[66]

Even without these apparently suspect ex-Mormon witnesses, the Rigdon link remained fraught with conflicting testimonies. In his final analysis, Robert Patterson resolved this problem by an unquestioning acceptance of the occasionally second-hand, but always confident statements of his “unimpeachable witnesses.”[67] Sidney Ridgon thus remained the prime mover in the Spalding plagiarism. While it was no longer deemed likely that he had the original manuscript, it was evident that somehow he had obtained a copy. Both Patterson and Dickinson agreed that the original manuscript remained with the family until 1833 when it probably fell into the hands of the Mormons. This, of course, was through the collusion of Philastus Hurlbut—who despite a half century of personal villification from the official Mormon press, continued to deny the charge.

Manuscript Refound

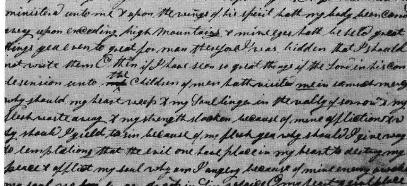

As events would shortly reveal, the manuscript which Hurlbut obtained from the trunk had indeed been given to Howe, who in turn published a generally accurate summary of its contents in Mormonism Unvailed. While the manuscript was lost sometime later, it was not destroyed in a fire. In retrospect it was still among Howe’s papers when he sold his business to Mr. L. L. Rice in 1839. Years later Rice unknowingly carried the manuscript to Hawaii, where in 1884 it was rediscovered among some old papers. The key to the identity of the “old, worn, and faded manuscript of about 175 pages” was the following statement, recorded on an empty page:[68]

The writings of Solomon Spalding, proved by Aaron Wright, Oliver Smith, John N. Miller and others. The testimonies of the above gentlemen are now in my possession.

—D.P. Hurlbut

Rice sent the manuscript, which he labelled “A manuscript story,” to his friend James Fairchild, President of Oberlin College, who in turn published his analysis of the discovery. Finding, as had L. L. Rice and others, no similarity in style, names or incidents between the manuscript and the Book of Mormon, Fairchild at first concluded that the Spalding theory “will probably have to be relinquished.”[69]

Later, while acknowledging that it was “perhaps, impossible at this day to prove or disprove the Spaulding theory,” he still found the affirmative case to be particularly weak. There seemed “no ground to dispute” the Mormon claim that Sidney Rigdon had been neither a printer, nor a resident of Pittsburg prior to 1822. The accepted view that the religious portions of the Book of Mormon were interpolations into a much shorter historical narrative he found “difficult—almost impossible, to believe.” Such sections were “of the original tissue and substance of the document,” and besides “a man as self-reliant and smart as Sidney Rigdon . . . would never have accepted the servile task.”[70]

Moreover, Fairchild reasoned, “in its general features the present manuscript fulfills the requirements of the ‘Manuscript Found’ “—an important point which Hurlbut and Howe had neglected to call to the attention of their early readers. It was, in fact, the story of a manuscript found in a cave containing an account “of the aboriginal inhabitants of the country.” Wrote Fairchild, “These general features would naturally bring it to remembrance, on reading the account of the finding of the plates of the ‘Book of Mormon.’ ” It had, after all, been “twenty-two years or more . . . since they had heard the manuscript read; and before they began to recall their remembrances they had read, or heard the ‘Book of Mormon,’ and also the suggestion that the book had its origin in the manuscript of Spaulding.” The cautious Fairchild nevertheless chose not to carry his speculations to a firm conclusion. Some people were saying that a second manuscript was “still in existence, and will be brought to light at some future day.” “It would not seem unreasonable to suspend judgment in the case until the new light shall come . . .s”

While raising important points, overlooked despite a half-century of vigorous discussion, Fairchild stopped short of the critical analysis which by then was possible. A closer examination of the testimonies collected in support of the Spalding theory would have yielded some surprising results. Eight witnesses had asserted that Spalding still had his story when he left Pittsburg. Following Spalding’s death in 1816 the manuscript—by the uncontradicted testimony of four of these witnesses—apparently remained stored for many years in a family trunk (its presence being reconfirmed in 1817, 1818, 1820 and 1831). The speculation that the manuscript had been copied in Pittsburg was never supported by either first- or second-hand testimony. In fact, six of seven people claiming some early first-hand knowledge about either Rigdon or Patterson’s printing office failed to recall or explicitly denied any contact between the two. (The exception, an 87-year old former postal clerk with a “marvelously tenacious” memory of events 65 years earlier.)

Nor did any of the fourteen claimants to knowledge of the text of Spalding’s writings issue any signed statements to the effect that there were two versions of his romance (“Roman” and “Book of Mormon”). When the “manuscript story” was rediscovered, the names of three of the original witnesses were found written in it by Hurlbut (quoted above) as confirming the story as the work of Spalding, but there was no verification of Howe’s claim about a second version. One of the three, Oliver Smith, with whom Spalding reportedly lived for six months in 1810, had a credible claim to knowledge of an earlier manuscript. It was in his home, according to Smith, that Spalding conceived, outlined and wrote over 100 pages of the Manuscript Found. Yet there was not the slightest hint in his original affidavit that Spalding was revising an earlier work. Most other witnesses did not claim familiarity with Spalding’s story until 1811, or early 1812, by which time the “earlier version” should long since have been abandoned. In fact, however, close examination of the Roman manuscript would have revealed even stronger evidence that it was not a discarded early version. On the back side of page 135 of the 171 page manuscript was a portion of an unfinished letter from Spalding to his parents referring to correspondence dated January 1812—almost certainly penned prior to the narrative text on the other side of the same sheet. (The reverse order would make no sense; and in all other cases the Spalding story appears on both sides of the manuscript pages.) Spalding thus was still at work on his Roman story well after several of Hurlbut’s witnesses claimed to have read or heard read Manuscript Found. Moreover, it appears that Spalding penned an additional 36 pages of text after January 1812, the probable year of his move to Pittsburg.[71]

Notwithstanding the limitations of Fairchild’s analysis, the rediscovery of the Roman “manuscript story” marked a turning point in the history of the Spalding theory. A recent review of Ohio authors and their books went so far as to date the downfall of the Hurlbut-Howe thesis to 1884.[72] To some early non-Mormon authors this assessment was partially correct. Theodore Schroeder, a staunch defender of the Spalding theory, noted in 1901 that “in the past fifteen years . . . all but two of the numerous writers upon the subject have asserted that the theory . . . must be abandoned.”[73] So far as the Mormons themselves were concerned, their opposition in 1900 was limited solely to “the densely ignorant or unscrupulously dishonest.”[74]

In retrospect, however, this hopeful judgment was several decades premature. A few writers, such as Hubert Howe Bancroft, in his History of Utah (1890), took a noncommital approach to the debate. Others, such as I. Woodbridge Riley, Eduard Myer and Walter F. Prince, moved beyond what they termed inconclusive “external” evidence on the source of the Book of Mormon to newly considered “internal” evidences pointing to Joseph Smith as the author.[75] As late as 1917, however, Prince found only “a few scholars, mostly within the last 15 years” who supported his view.[76]

In practice, the rediscovery of Spalding’s story had very little impact on the established arguments, or the frequency or confidence with which they were advanced. Thomas Gregg’s The Prophet of Palmyra (1890) offered, if anything, a less sophisticated discussion than had Eber D. Howe fifty-five years before; and the most popular turn-of-the-century work, William Linn’s The Story of the Mormons (1902), included little more than a condensation of Patterson’s Who Wrote the Book of Mormon? (1882).[77] The Mormons as well relied on their long established counter-arguments. Both LDS and RLDS churches, to be sure, rushed out “verbatim and literatim” editions of Spalding’s new found manuscript. And Orson Whitney, in his History of Utah (1890), quoted from it at great length, as did B. H. Roberts in New Witness for God (1909). Neither Whitney nor Roberts added much to the case presented just before the rediscovery of the manuscript in George Reynolds’ The Myth of the “Manuscript Found” (1883). Reynolds, who presumably was responding to the interest stirred by Patterson and Dickinson, in turn added little to the arguments advanced many years before by John E. Page (1843) and Benjamin Winchester (1840). On both sides of the debate, new testimonies had simply been piled onto old arguments.

The Twentieth Century

By 1900 Spalding advocates were left for the first time without the potential of new “living witnesses” to revitalize the otherwise shallow repetitions of their predecessors. Their efforts in the twentieth century, therefore, are little more than restatements of all that has gone before. The case is treated as both opened and resolved by Hurlbut’s original affidavits. Sidney Rigdon remained the likely agent in the plagiarism, but the means by which the whole thing was accomplished was no clearer than when Howe first speculated on the subject.[78]

A few subtle changes are apparent in the twentieth century discussions. The most conspicuous of these was the addition of scholarly trappings such as Theodore Schroeder’s copious footnotes. His profusely documented Salt Lake City ministerial tract, The Origin of the Book of Mormon (1901), was even serialized in the American Historical Magazine (1906). Although for the most part Schroeder’s work is an uncritical compilation of all the previously collected evidence, there was one distinct difference. It was finally clear, asserted Schroeder, that the Manuscript Found never was in the Spalding trunk—only an earlier version. No new evidence was introduced to support this departure from a near unanimous late nineteenth century consensus. Rather, the considerable evidence to the contrary was simply dismissed as less “satisfactory” than the claims of Patterson’s unimpeachable witnesses.[79] More recent Spalding supporters all have followed Schroeder’s lead on this point.

The only genuine innovation in the Spalding argument to be found in the twentieth century sources—before the past few months—is contained in Charles Shook’s otherwise undistinguished The True Origin of the Book of Mormon (1914). After studying Spalding’s Roman “manuscript story,” he concluded that it was considerably more than a source of confusion to those early but faded memories. To Shook there were unequivocal internal evidences that it was indeed an early version of the Manuscript Found, and thus the Book of Mormon. How else could one explain such anachronistic parallels as both Spalding and Smith writing of a “Great Spirit,” horses, iron, and the revolution of the earth around the sun. In 1932 George Arbaugh added to Shook’s list the similarity of Smith’s “elephants, cureloms and cummons” to Spalding’s “mammoons.” Arbaugh could even imagine the transition: “mammouth, mammoon, cumon, curelon.” As usual, however, no meaningful attempt was made to evaluate these parallels.[80]

The Spalding theory, if no longer undisputed, remained the dominant theory of the origin of the Book of Mormon well into the twentieth century. It was included in Stuart Martins’ The Mystery of Mormonism (1920); Harry Beardsley’s Joseph Smith and his Mormon Empire (1931); George Arbaugh’s Revelation in Mormonism (1932); and Alice Felt Tyler’s Freedom’s Ferment (1944). But time was rapidly running out. The “new Mormon history” was about to make its debut, and with it the first serious historical scholarship on Mormonism. No longer were studies in Mormon history to be primarily uncritical adversarial presentations, but rather they were to be characterized by a dispassion which for the first time would obscure the religious affiliation (Mormon or “non Mormon”) of the author. Such a setting was alien to the entire Hurlbut-Howe tradition of “scholarship.”

In 1945, Fawn Brodie’s No Man Knows My History was published, a book viewed by most Mormon scholars as transitional between the old “anti Mormon” school of Mormon history and the new Mormon history, and acclaimed in academic circles as the best biography yet published on the life of Joseph Smith. A 14-page “Appendix B” was devoted to “The Spaulding Rigdon Theory,”—the first in-depth assessment of the Hurlbut-Howe thesis by a modern historian.[81] Finding the pro-Spalding case to be “heaped together without regard to chronology . . . and without any consideration of the character of Joseph Smith or Sidney Rigdon,” Brodie proceeded to examine directly some of the facts on which the theory was built. Hurlbut’s affidavits she judged to be “clearly . . . written by Hurlbut, since the style is the same throughout . . .” The statements collected in the 1870’s and 1880’s were “all from citizens who vaguely remembered Spaulding or Rigdon some fifty, sixty, or seventy years earlier. All are suspect because they corroborate only the details of the first handful of documents collected by Hurlbut and frequently use the same language. Some are outright perjury.” Her conclusion, after reviewing the accumulated evidence and what was known of Rigdon’s pre 1830 activities, was that it was “most likely” that there had been “only one Spaulding manuscript.” Furthermore “if the evidence pointing to the existence of a second Spaulding manuscript is dubious, the affidavits trying to prove that Rigdon stole it, or copied it, are all unconvincing and frequently preposterous.” Even this “tenuous chain of evidence” broke altogether when it tried to “prove Rigdon met Joseph Smith before 1830.”

Brodie’s lead was followed not long thereafter by a number of distinguished scholars, notably Whitney Cross in The Burned-Over District (1950), and Thomas F. O’Dea in The Mormons (1957). Since 1945 serious students of Mormonism have treated the Spalding theory as little more than a historical curiosity. Until recently, most non-historians had forgotten about it altogether. The theory, however, did not disappear entirely. A well-preserved edition continued to be promulgated by the small remnant of a once distinguished school of Mormon pseudo-history. While generally unfamiliar to most students of Mormonism, such works as James Bales’ The Book of Mormon? (1958) and Walter Martin’s The Maze of Mormonism (1962), continue to retrace the ingenuous path of innumerable intermediary works back to the hard evidence of such early scholars as Patterson, Dickinson, Hurlbut and Storrs.

II

Just when it seemed that the Reverend Spalding might be forever buried in obscure academic footnotes or among the equally remote vestiges of the anti Mormon publishing industry, a whole new Spalding debate has suddenly been proclaimed. “Based on the evidence of three handwriting experts,” reported the Los Angeles Times news service of June 25,1977, “researchers have declared that portions of the Book of Mormon were written by a Congregationalist minister . . .”

The three California-based “freelance researchers”—Howard Davis, Donald Scales, and Wayne Cowdrey—had provided nationally known handwriting specialists—Henry Silver, William Kaye, and Howard Doulder—with photo copies of several original manuscript pages of the Book of Mormon. Comparisons were made with “specimens of handwriting in [Spalding’s] ‘Manuscript Story.’ ” According to the Times, Silver had stated his “definite opinion that all of the questioned handwriting (was) written by the same writer known as Solomon Spalding.” The other two experts were said to agree. Kaye reportedly had written in August 1976 “that it was his ‘considered opinion and conclusion that all of the writings were executed by Solomon Spalding.’ ” Doulder was quoted as stating, “This is one and the same writer.”[82] Shortly thereafter both Time and Christianity Today carried essentially the same story.[83]

Less conspicuously reported were the disclaimers issued shortly thereafter. In a press conference three days later, Silver stated that the Times had “completely misrepresented” him, and that he would be unable to give a definite opinion until he had examined original specimens of the handwriting.[84] After examining the Book of Mormon manuscripts, he reaffirmed that he still could not “definitely come to a conclusion” until he also had examined original pages of the “Manuscript Story.”[85] A week later, the 86-year-old Silver withdrew from the case. His doctor had advised against further travel, and he was also “fed up.” In addition to his displeasure at being misrepresented in the press, he was concerned that Walter Martin, whose Christian Research Institute was financing the study, “has a vendetta against the church.”[86] Interviewed later in his home, Silver added, “I don’t like their methods and their attack on the Church. I want no further part of this whole matter.”[87]

Meanwhile, William Kaye, second of the handwriting experts, arrived in Salt Lake City on July 7 to study a page of the original Book of Mormon manuscript. It appears that he, too, may have been misrepresented in the Times account, for he now stated that he could not give an opinion on the subject until he had examined all twelve disputed pages of the manuscript.[88] Accompanying Kaye was Jerald Tanner, perhaps the best known present-day publisher of “anti-Mormon” literature. Tanner explained later that he was there only at the request of a friend, and felt the handwriting allegations to be a “poor case.” While disclaiming handwriting expertise, he said there were “too many dissimilarities” evident, which “just an ordinary layman could spot.”[89] Other observers, including Dean Jessee, leading authority among Mormon historians on early Church holographs, also found the differences readily apparent. Said Jessee, “Any competent handwriting analyst will easily spot numerous differences in the two hands. In fact, even the untrained eye can see the basic differences.”[90]

Kaye, who also has examined the Spalding manuscript at Oberlin College, returned to LDS Church archives on July 20 to examine the remaining eleven pages of the original manuscript. The same day the third of the original group of experts, Howard Doulder, also visited church archives to study the manuscripts. Neither issued a statement following his one day visit; final reports* are expected within a few weeks.[91]

Mormon spokesmen have been described as “unruffled” throughout these developments. LDS “press spokesman” Don LeFevre issued the expected official testimonial, “.. . Truth is unchanging, and the truth of the matter is that the Bookof Mormon is precisely what the church has always maintained it is. . . .”[92] Church Historian Leonard Arrington was more direct, “The whole theory is ridiculous.”[93]

Little study is necessary to discover that the confidence of Church officials in the face of the recent claims is well justified. What negligible historical evidence there is for the Spalding theory is itself incompatible with the recent claims. Virtually every witness claiming to have read Manuscript Found described it as a strictly secular, historical work. Sidney Rigdon and Joseph Smith were always credited with the extensive scriptural and religious inter polations. Yet the pages recently alleged to be in the hand of Solomon Spalding (covering 1 Nephi 4:20 to 1 Nephi 12:8) are perhaps as heavily “religious” as any passage of comparable length in the entire book. Most of the narrative is taken up with a detailed description of a prophetic dream by Lehi, its inspired interpretation, and a subsequent vision by Nephi.

As a corollary, Spalding advocates—particularly following the rediscovery of the Roman “manuscript story”—denied that any of the Book of Mormon was “verbally” the work of Spalding. Charles Shook, for example, was “sure that no anti-Mormon writer, who has given the matter due consideration, holds to any such theory.” Spalding’s Roman story was just too incompatible stylistically with the Book of Mormon to argue otherwise.[94] Now, however, the handwriting claims would have one believe that Spalding had contributed to the Book of Mormon both key portions of the religious structure and the basic writing style.

In addition to the historical obstacles, the handwriting theory faces a seemingly insurmountable challenge from the Book of Mormon manuscripts themselves. The twelve pages of disputed authorship were part of a group of twenty pages which give every appearance of coming from a single copybook, with the same ink apparently used on every sheet. The handwriting on the remaining eight pages of the group already has been identified as that of known Book of Mormon scribes—Oliver Cowdery and, tentatively, John Whitmer.[95] The California researchers attempted to discount the major problem this raises (Cowdery being age nine when Spalding died) by proposing—in Time’s words, “somewhat lamely”—that “Smith was so poverty-stricken that he and his aides might have stuck sections of Spalding’s manuscript between pages of their own in order to save paper.”[96]

The problem, however, is not nearly so simple. At the top of each page of manuscript is a one-line summary of the narrative appearing on that page. The summaries appearing on the disputed pages are in the same handwriting as the text below. What appears to be this same handwriting summarizes the text of two of the three preceding pages of manuscript, the body of which is written by Oliver Cowdery and, tentatively, John Whitmer.[97]

Nor are the problems for the “handwriting theory” restricted to the Book of Mormon manuscripts alone. Church historians have also produced the original transcription of a revelation dated June 1831—some fifteen years after Spalding’s death—which appears to be the work of the same unidentified scribe who wrote the disputed twelve pages. Published as D&C 56, this revelation dealt in explicit terms with personalities and circumstances not present before the time it was dated. Specific guidance is given to Thomas B. Marsh, Ezra Thayre, Newel Knight and Joseph Smith. As described by Dean Jessee, such posthumous regulation of Church affairs would be nothing short of “miraculous.”[98]

The ultimately unrelated question remains, who did record the disputed twelve pages? Both Reuben Hale, brother of Emma Smith, and Martin Harris have been suggested. Current thinking favors Harris, who is known to have been present both in Kirkland, Ohio, in 1831 when D&C 56 was written, and also Fayette, New York, two years earlier when the relevant portions of the Book of Mormon were dictated. On several occasions Harris was identified, by Emma Smith and others, as one of the scribes for the Book of Mormon.[99] Unfortunately, no definite specimen of his handwriting has been located.

While for the past thirty years the Spalding theory has been a dead issue, it has never truly disappeared. The very imprecision of the original arguments, so integrally tied to the eventual abandonment of the theory by scholars of Mormonism, has served to assure its preservation. However high the possibilities, no one has ever been able to “prove” in any absolute sense that the Hurlbut affidavits were erroneous recollections, deliberate or otherwise. Superficial analyses, shaped largely by an a priori assumption that Joseph Smith was incapable of producing the Book of Mormon alone, will no doubt continue to find “hard evidence” in the persisting trace of uncertainty—and carry the Spalding corpus perpetually onward. So long as the subject remains, in O’Dea’s words, a “not-quite-solved” historical problem, this will probably ever be so. One therefore can reasonably expect that new variants will, like the influenza, reemerge every now and then. The strength of these will probably be, as in the most recent instance, inversely proportionate to the publicity with which they are heralded. One newspaper headlined this latest episode, “BOOK OF MORMON’S AUTHENTICITY DOUBTED BY HANDWRITING EXPERTS.” More aptly the title could have been, “THE LATE REVEREND SPALDING DISINTERRED . . . BUT SLATED FOR REBURIAL.”

The standard references on the Spalding theory in recent years include the following: Leonard Arrington and James Allen, “Mormon Origins in New York: An Introductory Analysis,” BYU Studies 9:241-274; Fawn Brodie, No Man Knows My History (New York, 1945), Appendix B; Marvin S. Hill, “The Role of Christian Primitivism in the Origin and Development of the Mormon Kingdom, 1830-1844,” (PhD Dissertation, University of Chicago, 1968), pp. 80-97; an d Francis W. Kirkham, A New Witness for Christ in America: The Book of Mormon (Independence, Mo., 1942), especially volumes 1 and 2. Many of the works cited below are also useful sourcebooks on the subject, notably the books of Ellen Dickinson, Robert Patterson, George Reynolds, and B. H. Roberts.

[1] Joseph Smith termed the infraction, for which Hurlbut was excommunicated in late June, 1833, “lewd and adulterous conduct.” Donna Hill recently has asserted that “unchristianlike conduct” was meant to describe the use of obscene language to a young member. She also provides additional background on Hurlbut in her Joseph Smith: The First Mormon (Garden City, 1977), pp. 46, 67, 103, especially 155-157. Most of the Mormon sources cited below discuss him as well.

[2] Henry Lake, John N. Miller, Aaron Wright, Oliver Smith, Nahum Howard and Artemas Cunningham.

[3] Eber D. Howe, Mormonism Unvailed (Painesville, Ohio, 1834), pp. 278-287.

[4] Ibid., pp. 287-288.

[5] The “Manuscript Found:” Manuscript Story, by. Rev. Solomon Spaulding, Deceased (Salt Lake City, 1886), pp. 1-3.

[6] See Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Period I, B. H. Roberts, ed. (Salt Lake City, 1902), 1:16.

[7] The “Manuscript Found” . . . , pp. 74-75- Compare Mosiah 8:13-19, Alma 37:23, etc. Allusions to such “urim-and-thumim”-like devices were hardly unique to Spalding and the Book of Mormon. Contemporary references to the Indians possessing such instruments included Ethan Smith’s View of the Hebrews (1823) and Elias Boudinot’s Star of the West (1816). Whatever the similarities of Spalding’s stone and that found in the Book of Mormon, their uses diverged somewhat: “[Hamack] could behold the galant & his mistress in their bed chamber & count all their moles warts & pimples.”

[8] Other members of the Spalding cast: Baska, Bithawan, Colorangus, Crito, Drafolick, Elseon, Gamasko, Gamba, Geheno, Habelon, Hamkien, Hamkol, Hamul, Hanock, Helicon, Heliza, Kelsock, Labarmack, Lakoon, Lambon, Lobanko, Lucian, Numapon, Owhahon, Ohons, Rambock, Ramoff, Sambal, Suscowah, Taboon, Thelford, Tolanga, and Trojanus.

[9] Howe, op. cit., pp. 278, 288. The first explicit published reference alleging Spalding as the ultimate author of the Book of Mormon appeared in the Painesville Telegraph, January 31, 1834. A short notice announced that the details of Hurlbut’s findings shortly would be published, presumably referring to Mormonism Unvailed. Several weeks earlier, the Wayne Sentinel reported that Hurlbut had learned from the widow of an unnamed but “respectable clergyman now deceased” that the Book of Mormon was based on a manuscript penned by her late husband. See reprinted accounts in the January 18, 1834 editions of the Chardon Spectator & Geauga Gazette, and Guernsey Times (Cambridge, Ohio).

[10] George Reynolds, A Dictionary of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, 1891), p. 294; Howe, op. cit., p. 23.

[11] Howe, op. cit., pp. 278, 288.

[12] Identified by Pratt as Zion’s Watchman and the New-York Evangelist. Also published in New York in 1838 were Origen Bacheler’s Mormonism Exposed and James M. McChesney’s An Antidote to Mormonism. Both advocated the Spalding theory. See Francis W. Kirkham, A New Witness for Christ (Salt Lake City, 1951, revised 1959), 2:159-163.

[13] Parley P. Pratt, Mormonism Unveiled (New York, 1838), pp. 40-42, reprinted in Pre-Assassination Writings of Parley P. Pratt (Salt Lake City, 1976).

[14] Davison’s statement is found in John E. Page, The Spaulding Story Concerning the Origin of the Book of Mormon (Pittsburg, 1843), republished by the Reorganized Church (Piano, Illinois, 1865), pp. 2-4, and many later works; her earlier report is in Howe, op. cit., p. 287.

[15] As quoted in The Religious, Social, and Political History of the Mormons . . ., Samuel M. Smucker, ed. (New York, 1856), pp. 45-48. For an early problem between Rigdon and Hurlbut, see Donna Hill, op. cit., p. 157.

[16] As quoted in Page, op. cit., pp. 13-14, and others.

[17] Particularly in passages providing “new” support to the Hurlbut-Howe thesis. For example:

—Rigdon was connected with Patterson’s printing office “as is well known in that region, and as Ridgon himself has frequently stated.” His “ample opportunity” to copy her husband’s manuscript was “a matter of notoriety and interest to all . . .” (Recall Mrs. Davison’s apparent failure to mention Ridgon in her previous discussion with Hurlbut.)

—The style of the Manuscript Found, since it described people of “extreme antiquity” (those who built the mounds) “of course, would lead him to write in the most ancient style, and, as the Old Testament is the most ancient book in the world, he imitated its style as nearly as possible.”

—Spalding’s “acquaintance with the classics and ancient history” enabled him “to introduce many singular names, which were particularly noticed by the people, and could be easily recognized by them.” As an illustration she briefly (and probably inaccurately) summarized not her own experience, but that of her brother-in-law, John* Spalding.

The Davison statement concluded with a faintly “minsterial” ring: “Thus a historical romance, with the addition of a few pious expressions, and extracts from the sacred scriptures, has been construed into a new Bible, and palmed upon a company of poor deluded fanatics as divine.” The critical quotation is from Theodore Schroeder, The Origin of the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City, 1901), pp. 11-12. Schroeder’s work was also published in three parts in the American Historical Magazine, beginning in September, 1906.

[18] As quoted in Page, op. cit., pp. 5-6, and others.

[19] John A. Clark, Gleanings By the Way (Philadelphia, 1842), pp. 259-266.

[20] Ibid., p . 265.

[21] Benjamin Winchester, The Origin of the Spaulding Story (Philadelphia, 1840), p. 11.

[22] Ibid., pp. 8-9.

[23] Ibid., p. 13.

[24] As quoted in Page, op. cit., p. 7, and others, who cite a pamphlet by Rev. Samuel Williams, “Mormonism Exposed,” published in Pittsburg in 1842. Note that except for his significant failure to implicate Rigdon, Patterson’s account was similar to that of Mrs. Davison.

[25] Robert Patterson, Who Wrote the Book of Mormon? (Philadelphia, 1882), p. 7.

[26] Ibid., pp. 7, 9.

[27] John C. Bennett, Mormonism Exposed (New York, 1842); Henry Caswell, The City of the Mormons (London, 1842); Clark, op. cit.; Daniel P. Kidder, Mormonism and the Mormons (New York, 1842); Nathan B. Turner, Mormonism in All Ages (New York, 1842); and Williams, op. cit. The following year Caswell added The Prophet of the Nineteenth Century (London, 1843). Bennett, late of the Mormon hierarchy, added nothing new to the Hurlbut-Howe thesis.

[28] Clark, op. cit., pp. 266-267.

[29] Turner, op. cit., p. 213. Turner attributed his information to “other sources.” Smith actually had worked for Stowell in 1825 and 1826. No evidence was ever produced that there was any contact between him and those who held the trunk, and after a few decades this notion was finally abandoned.

[30] Ibid., p . 211.

[31] Page, op. cit.

[32] Winchester, op. cit., p. 14.

[33] Page, op. cit., p. 7-8.

[34] Patterson, op. cit., p. 9.

[35] Page, op. cit., p. 8-9.

[36] Ibid., p. 9-11.

[37] Ibid., p. 10.

[38] O. Turner, History of the Pioneer Settlement of Phelps and Gorham’s Purchase (Rochester, 1851), p. 214. Hurlbut also railed to find support for the Spalding theory in the Palmyra area. See Donna Hill, op. cit., p. 146.

[39] Patterson, op. cit., p. 8.

[40] A few mid-century works advocating some variation of the Spalding theme (see also note 24 above): John Bowes, Mormonism Exposed (London, 1850?); Robert Chambers, History of the Mormons (1853?), reprinted in Chambers’s Miscellany of Instructive & Entertaining Tracts (London, 1872); Benjamin G. Ferris, Utah and the Mormons (New York, 1854); Samuel M. Smucker, op. cit. (1856); J. W. Gunnison, The Mormons, or, Latter-day Saints, in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake (Philadelphia, 1856); T. W. P. Taylder, The Mormon’s Own Book (London, 1857); John Hyde, Jr. (an ex-Mormon), Mormonism: Its Leaders and Designs (New York, 1857); and Pomeroy Tucker, Origin, Rise, and Progress of Mormonism (New York, 1867). Of these, the most popular as secondary sources for later works on the Spalding theory were Chambers, Ferris, Smucker, Gunnison, Hyde, and Tucker.

[41] Benjamin Ferris, the former Secretary of Utah Territory, published his Utah and the Mormons in 1853. As described by him, the Manuscript Found told the story of “a family of Jews—the father, Lehi, and four sons, Laman, Lemuel, Sam, and Nephi, with their wives” who departed “Jerusalem into the wilderness, in the reign of Zedekiah.” “Besides the names already mentioned, the names of Mormon, Moroni, Mosiah, Helaman, and others, frequently occur in the [Spalding] book.” Ferris was not alone in imaginative reconstructions. An anonymous work appearing the same year—republished later as Smucker’s History of the Mormons—added somewhat less ambitiously that two of the “principal characters” in Spalding’s manuscript were Mormon and “his son” Moroni. Ferris, op. cit., p. 51. [Charles Mackay], History of the Mormons (Auburn, 1853); Smucker, op. cit., p. 40. Chambers, op. cit., made the same claim.

[42] The New American Cyclopedia, George Ripley and Charles A. Dana, ed. (New York, 1863), 11:735. Patterson, who attributed this assertion to “Appleton’s [the publisher] Cyclopedia,” searched Pittsburg papers for the advertisement without success. He writes that when the author of the article was “interrogated,” he “could not recall his authority for the statement, but was positive that he had ample warrant for it at the time of writing.” (Patterson, op.cit., p. 7)

[43] Tucker, op. cit., pp. 28, 46, 75, 121. Typically, Tucker’s claim, though without previous support, received corroborative testimony of sorts over a decade later. Abel Chase, in 1879 indistinctly recalled that when he was a boy of 12 or 13, he had seen someone in the Smith home said to be Ridgon, about 1827. Lorenzo Saunders, in 1885, after puzzling over the matter for thirty years, concluded that he too had seen Ridgon, both in 1827 and 1828. See W. Wyl, Mormon Portraits (Salt Lake City, 1886), p. 230-231; and Charles A. Shook, The True Origin of The Book of Mormon (Cinicinnati, 1914), p. 132, and Fawn M. Brodie, No Man Knows My History (New York, 1945, rev. ed., 1971) p. 453.