Articles/Essays – Volume 31, No. 3

The Times — They Are Still A’ Changin’

When Allen Roberts and I began our tenure with Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought in 1992, it was a craze-filled time, not unlike that of the 1960s—the debate over academic freedom at Brigham Young University, the excommunications of the “September Six,” the LDS church’s condemnation of participation in the Sunstone Symposium, or even the discouragement BYU faculty members felt from publishing in either Sunstone or Dialogue created a sort of tension in Mormon studies that was slow to dissipate. We stepped into our roles as editors of this journal believing that we would steer it through what might be troubled waters and, perhaps more importantly, that the direction we pointed our vessel would matter, that it would make a huge difference.

When we first met with Ross and Kay Peterson, Dialogue’s previous editors, they showed us their offices and talked to us about the joys and difficulties that came with running Dialogue. Ross said the journal was largely driven by submissions. I didn’t believe him. I believed instead, somewhat naively, that the journal would take on the shape of our vision, our dreams of a more inclusive community, of better ways of being together in this amorphous world of Mormonism.

I have spent considerable time recently thumbing through the issues we tried so carefully to produce and have realized that in large measure he was right. I am proud of what we have done, although our choices have sometimes met with criticism. We have tried to provide a place where voices not always heard in this “dialogue” have been included, a greater variety has sometimes graced our pages.

I miss the historical articles written by BYU professors, the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute fellows and others, the essays written by those who have chosen for whatever reason not to appear next to an ever more diverse grouping. But it has not been by design. We have invited many to write, but our issues are largely shaped by what came to us and what we thought represented the best in that group.

In all of it, scripture studies and personal essays, fiction and historical studies alike, I am moved by how earnestly we Mormons try to understand what our lives mean, where we fit into the universe, and how we might better live.

There is a wonderful passage in Barry Lopez’s book Arctic Dreams in which he considers the many valuable lessons we might learn from the earth, from the natural world around us.

One of the oldest dreams of mankind is to find a dignity that might include all living things. And one of the greatest of human longings must be to bring such dignity to one’s own dreams, for each to find his or her own life exemplary in some way. The struggle to do this is a struggle because an adult sensibility must find some way to include all the dark threads of life. … The dignity we seek is one beyond that articulated by Enlightenment philosophers. A more radical Enlightenment is necessary, in which dignity is under stood as an innate quality, not as something tendered by someone outside.

He continues: “The other phrase that comes to mind is more obscure. It is the Latin motto from the title banner of the North Georgia Gazette: per freta hactenus negata, meaning to have negotiated a strait the very exist ence of which has been denied. But it also suggests a continuing move ment through unknown waters. It is, simultaneously, an expression of fear and accomplishment, the cusp on which human life finds its richest expression.”

What has been most striking and moving to me as we have read hundreds of articles, essays, and stories submitted to Dialogue is this very effort—this longing to bring dignity to our lives and to enable others to do the same. The second notion is the idea that this often takes us through very difficult terrain, places that some deny exist or would be possible to traverse. As frightening and as dangerous a prospect as it might feel at times, it is well worth the risk and the effort. It is the depths we probe, the most difficult and challenging walls we climb which make life, as Lopez says, find its richest expression.

Native American writer N. Scott Momaday, in an essay about the way his grandmother enriched his life with her stories, describes the power of carefully chosen words and the way those words and ideas help us span the gaps that divide us as human beings. He writes:

When she told me those old stories, something strange and good and powerful was going on. I was a child, and that old woman was asking me to come directly into the presence of her mind and spirit; she was taking hold of my imagination, giving me to share in the great fortune of her wonder and delight. She was asking me to go with her to the confrontation of something that was sacred and eternal. It was a timeless, timeless thing; nothing of her old age or of my childhood came between us.

I think when one of us submits our work for publication, it requires a monumental act of trust. We assume that our work will be scrutinized, measured perhaps against certain standards we hold in common about excellence, care, and interpretation. We ask that it be respectfully and thoughtfully considered. In the way Momaday describes, we also ask others (an audience we presumably respect) to come “into the presence” of our minds and spirits, to try to see the world or our history or what we care about from our vantage point. I value this experience and consider it one of the great benefits of having worked with Dialogue, and to have shared it with others has made the experience more meaningful.

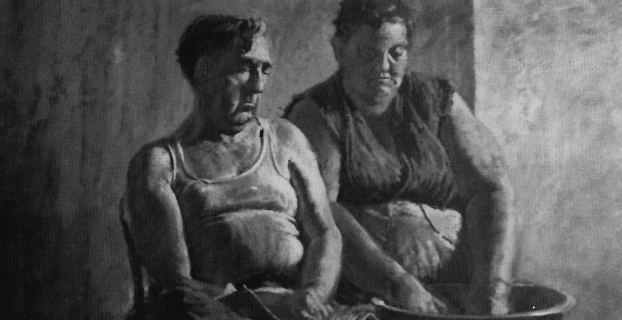

It has also been a great privilege to have worked with such fine men as Allen Roberts and Gary Bergera. Allen’s probing and fine-tuned mind has pushed us always to wait for the stronger article, the more carefully written or interpreted piece; his own standards of excellence have touched everything we have done. His fine sense of what is beautiful and aesthetically of value has brought the level of art produced in Dialogue to a new height. We are proud of our covers, the art that has graced our pages, and the variety it represents. Our timeliness and regular production schedule have been Gary’s work. His editing and recommendations to authors have improved the quality of work we have published. Be sides that, I consider Gary one of the finest human beings I have been privileged to know. He is a true and constant friend.

The past six years have also been years of great loss—many of our own mentors and friends have died—including Lowell Bennion, Sterling McMurrin, Delmont Oswald, Lowell Durham, Robert Paul, and Sam Tay lor—each taught us by his example to care about the quality of the lives we live and what we bring to each other as members of this community.

The members of our editorial board—Susan Howe, John Sillito, Alan Smith, Bill Mulder, and Michael Homer—have been tireless in their efforts to improve the quality of the journal, and we acknowledge their important contribution. We also appreciate the fine technical and creative work provided by Warren Archer, our art director, and Mark J. Malcolm, the production manager.

Unlike so many returned missionaries who stand before congregations and emotionally describe their missions as the best two years of their lives, I am at a loss to know how best to describe these years with Dialogue. It has certainly been an interesting time. To describe it as a profoundly moving experience is so vague as to lose a sense of what it has meant to me on a personal level. I value the “dialogue” that has transpired; it will stay with me and, I believe, make me a better person.

But “the times, they are a’ changin’.” In some ways the next editors of Dialogue have been preparing for this new challenge for decades—both Neal and Rebecca Chandler are writers—Neal a well known writer of fiction, and Becky a master teacher of English at Laurel School, a private school for girls in Shaker Heights, Ohio.

It seems appropriate that, in the wake of all the hoopla about the Mormon trek west, Dialogue should make the trek back East, missing Kirtland by a hair and landing instead in Cleveland with the Chandlers. We believe this move will strengthen Dialogue and pump new life and en ergy into the enterprise.

Neal Chandler is the director of the Creative Writing Program at Cleveland State University where he also teaches fiction writing, play writing, and English composition. Since 1995 he has been business manager of the Cleveland State University Poetry Center, an important publisher of contemporary poetry. Since 1990 he has been director of Imaginations, a successful writers’ workshop and conference held annually in Cleveland. He serves as a board member for the CSU Poetry Center, Writers’ Conferences and Festivals, the Writers’ Center of Greater Cleveland, and on the editorial board of Weber Studies. He has been a frequent presenter at Sunstone symposia, and his essays and short stories have appeared in Sunstone, Dialogue, and Weber Studies.

Rebecca Worthen Chandler’s B.A is in history. She holds an M.Ed, degree from Brigham Young University, and has her own editing company: Works in Progress. Her many editing projects include the summer 1980 issue of Exponent II and various other newsletters and publications. Her essays and short stories have been published in Dialogue, Sunstone, Exponent II, the Ensign, and the New Era. She has taught in high schools and middle schools in Ohio and Utah, and has taught English composition and teacher education at Cleveland State and Brigham Young universities. For six years she was director of Laurel’s Gifted Writers’ Workshop, and she currently directs and coaches Laurel’s writing team in Ohio’s Power of the Pen competition. In 1995 her team won the state championship. Neal and Becky have eight children and six grandchildren.

Beginning with the spring 1999 issue, their first as new editors, we wish them godspeed as they chart Dialogue’s future course.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue