Articles/Essays – Volume 29, No. 1

The Uncertain Dynamics of LDS Expansion, 1950-2020

More than ever before the LDS church seems to measure its milestones in terms of numbers. Almost every issue of the Church News and the En sign includes an article or a graphic that highlights the latest indicator of “Church Growth.”[1] Sometime this year or next, while celebrating the Utah State Centennial and the Pioneer Sesquicentennial, Mormons will doubtless point to two more milestones: (1) 10 million members and (2) the rise of non-North Americans to a position of numerical majority in the “Worldwide Church.” Who would have predicted twenty-five years ago such rapid change in the size and regional make-up of church member ship? We have been asked to project the geography and demography of Mormondom twenty-five years from now; fortunately for us, Dialogue readers will have to wait that long to decide how prescient we have been.

In 1972, when President Harold B. Lee dedicated the new Church Office Building just east of Temple Square, he presided over a mere 3 million members, 85 percent of whom were Americans or Canadians. Yet he sensed a trend well under way, declaring that Mormonism already had become more than a Utah or an American church, with members in some seventy nations. Moreover, he claimed rapid growth posed the greatest problem facing the church.[2]

That problem persists, “but what a remarkable and wonderful challenge that is,” in the eyes of President Gordon B. Hinckley, who in 1995 was called to preside over “a great global society” of 9 million Latter-day Saints in 150 countries.[3] More than any previous generation of general authorities, he and his associates must view the expansion of the church during their ministry as fulfillment of a prophecy voiced by Joseph Smith in 1842: “No unhallowed hand can stop the work [of the Latter-day Saints] from progressing; persecutions may rage, mobs may combine, armies may assemble, calumny may defame, but the truth of God will go forth boldly, nobly, and independent, till it has penetrated every continent, visited every clime, swept every country, and sounded in every ear, till the purposes of God shall be accomplished, and the Great Jehovah shall say the work is done.”[4]

Proclaiming the gospel probably commands more of the church’s attention than either of its two other major missions: perfecting the Saints and redeeming the dead. Leaders must find it easier to measure the results of missionary work, and they naturally take pride in touting the constant increases in converts, wards, stakes, and missions that demand so much of their time.

What do such numbers—whether graphed or mapped—reveal about the changing composition and distribution of Mormons? How much confidence can we give them as a basis for forecasting Mormonism’s future into the twenty-first century? For this special issue of Dialogue, we have combined our geographic and demographic perspectives to provide an overview of the dynamics operating to shape the configuration of Mormondom—the world’s Latter-day Saint population—for the period 1950- 2020. First, we regionalize the highly uneven distribution of the current membership, using both absolute and relative numbers. Then we assess various projections of both general and regional growth rates of the church for the next twenty-five years. Third, we examine the most important variables which make forecasts that far into the future highly problematic, even, we suspect, for prophets. Finally, we consider two of the most important challenges facing Mormonism because of its expansion.

Geographic Patterns of Membership Distribution

Any mapping of the LDS membership requires a few observations at the outset, since numbers and graphics can mislead if not read properly. Although Mormons reject infant baptism, they count as members any “children of record” blessed and named soon after birth. Thus unbaptized children of members (until age eight) make up an important share of the LDS population (about 15 percent among Americans). Moreover, in spite of its diligent clerks and computerized records, the church still loses track of an unspecified number who drift away from the faith and leave their local branches or wards without forwarding addresses. The “Missing Members” file presumably accounts for the discrepancies sometimes found between lower regional and higher churchwide totals. Those actually excommunicated, and thus no longer counted, likely amount to only a fraction of 1 percent.[5]

Between the two extremes—blessed but unbaptized, baptized but unbelieving members—falls the majority of Latter-day Saints. They too represent a spectrum of commitment to the faith, and their activity levels not only vary among regions but also change over the life course.[6] In reality, despite outsiders’ stereotypes, Mormonism, like any religion, embraces a diverse group.

LDS membership counts appear even more inflated when compared to surveys of self-identified religious affiliation based on probability samples. At least in the United States this overreporting of Mormons stands in contrast to the underreporting of members in most other churches. Such inflation likely looms higher in areas of the world where the church has lower retention rates. The figures cited in this essay, unless otherwise footnoted, come from the biennial Deseret News Church Almanac, first published in 1973.

Despite due allowance for the wide gap between the nominal members and true believers counted by the church, we must acknowledge that Mormonism has experienced an impressive annual increase in numbers ever since 1950. Equally striking changes have occurred in the spatial dispersion of Mormons, with the rapid rise in converts in certain countries of Africa, East Asia, and, most of all, Latin America.

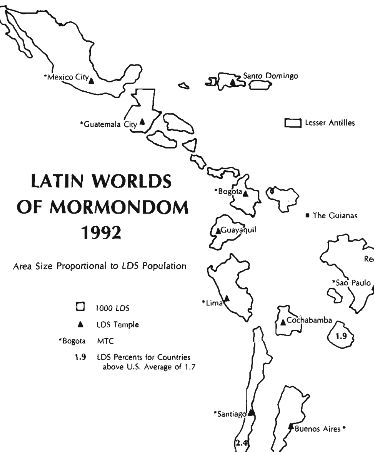

To make visual the geographic distribution of the current member ship, we have drafted three cartograms (Figs. 1-3), maps that make the actual area of a state or country proportional to, in this case, the size of its Mormon population.[7] To the individual political units we have added the LDS percentage of the total population if it equaled or exceeded the U.S. average of 1.7 percent at the start of 1992. In addition, we have located the sixty temples and fifteen Missionary Training Centers that the church has built (or plans to build) as of 1 July 1995, and around which the largest numbers of Latter-day Saints appear to cluster.

In effect, the cartograms collapse the twenty-two Areas of the world now used by the church for administrative purposes into three global realms: a North America area that still contains a bare majority of the membership; a Latin America that includes nearly one-third; and an Eastern Hemisphere with four vast and disparate regions—Europe, Africa, Asia, and Oceania—that together account for the remaining one sixth.[8]

Despite at least a minimal presence in most countries of the world, Mormonism remains strongly based in western North America and is deeply rooted only in the U.S. Intermountain West and in a few islands of Oceania. As the data in Figure 1 indicate, more than three-fourths of Mor mons in the U.S., and two-thirds of those in Canada, are westerners; and two-thirds of the western U.S. Saints live in the so-called Mormon Culture Region centered in Utah.[9]

Only the thirteen Western States and Alberta have an LDS percentage higher than the U.S. national average, ranging from Alberta’s 2.25 per cent to Utah’s 77 percent as of 1992. Moreover, while LDS wards and stakes have spread across most of the eastern half of North America since 1950, the general distribution pattern has changed little since 1970, despite the sharp drop in the U.S. and Canadian shares of the worldwide membership.[10]

The most impressive change on the world map of Mormondom has taken place in the other two Americas: Middle America (Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean) and South America. With roughly one-third of the total and nearly two-thirds of the membership outside North America, Latin America deserves its own cartogram (see Fig. 2). Mexico, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, and Chile stand out on this map, especially when compared with a cartogram for Latin America’s entire population, although their dominance is not as great as that of the Intermountain West. As David Knowlton observes in his essay herein, the size and extent of the LDS Latin American population still make Mormonism a predominantly American faith. Having proclaimed the “whole of America” as Zion in 1844, Joseph Smith now would undoubtedly include all three Americas in the 1990s.[11]

[Editor’s Note: For Figures 1–3, see PDF below, pp. 12–15]

Even when combined, the other four regions, shown in Figure 3, claim less than 15 percent of the world’s Mormons. Europe and Oceania each have small but relatively stable shares, but Oceania’s Saints make up a sizable portion of all the Pacific islands’ people, particularly in the two Samoas and in Tonga (with 25-33 percent each). Although Mormonism depended heavily upon European converts for its nineteenth-century growth, modern Europe, even Great Britain (which claims almost half of all European Saints), has only a minuscule number of Mormons compared to its total population. Nowhere in East Asia or in Africa, where Mormons are either more numerous or increasing more rapidly than in Europe and Oceania, do the Saints add up to more than .5 percent in any country.

Thus only on the Christianized or Westernized edges of the eastern hemisphere has the church established significant beachheads. Perhaps because of their physically and politically fragmented natures, these four regions have nevertheless received more than their share of temples (25 percent of the world’s temples versus 15 percent of its members). All but absent from this cartogram (Fig. 3) are the non-Christian Asian and African realms that embrace three-fifths of the world’s people. Finding ways for Mormonism to penetrate these populous and culturally diverse worlds of Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Taoism will doubtless challenge LDS leaders throughout the twenty-first century. Should Mormon ism succeed where other Christian faiths have failed, it would represent a religious change of miraculous magnitude in the world.

Projecting Church Growth Rates

What of the church’s future in areas where it already has at least solid footholds? How will the location, size, and composition of its member ship change in the foreseeable future? Among the few efforts to tackle the task of plotting possible trajectories, the work of sociologist Rodney Stark has attracted the most attention. In his oft-cited 1984 essay he pointed to LDS growth rates exceeding 50 percent for each decade since 1950. Then he made simple projections by region of Mormon membership for the next century.[12]

A decade later Stark returned to his forecasts to see how they compared with actual growth. Given the church’s 67.3 percent increase in members during the 1980s, he found strong support for his vision of Mormonism as an emerging world religion. His latest projections to the year 2080 include a “conservative” estimate of 63,415,000 (30 percent per decade) and an “optimistic” estimate of 265,259,000 (50 percent per de cade).[13] However, if his optimistic growth rate proves correct for only the first sixty years, and if growth then remains flat for the final twenty years, the number of Mormons in 2080 would fall 120 million short of the “optimistic” total.

Matthew Shumway, a BYU geographer, recently mapped the changing regional composition of church membership from 1920 to 2020. Un fortunately, he used percents rather than actual numbers, did not indicate how he derived the annual growth rates for his regional projections, and did not enumerate rates for all ten of the regions mapped. “If current regional growth trends continue,” he concluded, “the demographic makeup of Church members will be dramatically different in the future.” In the year 2020, he calculated, Latin Americans would account for about 71 percent of all LDS while North America and Europe combined would account for only 11 percent.[14]

We propose a different set of projections driven by data presented in Table 1: regional growth rates by decade from 1950 to 2000 (with figures for the 1990s extrapolated from increases in 1990-94). Although rates re main high, they have dropped by at least half in every region except Africa since 1990.

Table 1: Regional Percentage Growth Rates per Decade, 1950s–90s

| Decade | Africa | Asia | Canada | Europe | Lat. Am. | Oceania | U.S. |

| 1950–60 | 123% | 1731% | 69% | 41% | 569% | 59% | 54% |

| 1960–70 | 102 | 472 | 75 | 185 | 850 | 135 | 42 |

| 1980–90 | 351 | 216 | 57 | 68 | 235 | 99 | 50 |

| 1990–2000 | 311 | 97 | 30 | 35 | 105 | 42 | 22 |

Source: Deseret News Church Almanacs. 1990 data equal average of 1989/1991.

This latest trend makes any prediction risky. Should we ignore the early 1990s as a brief aberration or consider them the beginning of a new and downward trend? Both Asia and Latin America show reductions in growth rates since 1970, and Africa may do the same after its upward surge following the end of the church’s priesthood ban for blacks in 1978. Table 1 also reveals that since 1950 Europe and the United States have usually shown the lowest growth rates while Oceania’s and Africa’s levels have fluctuated the most.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 2, see PDF below, p. 18]

The instability in these rates suggests caution in assessing the data in Table 2 (and later in Table 4). Table 2 presents two series of projections. The first, based on the regional growth of the 1980s, probably represents an unduly optimistic forecast. The second, based on 1990s rates, should prove more realistic if declines persist into the next century in the fast growing realms of Latin America and Asia.

The slower growth rates in Latin America and Asia might result from either or both of two conditions. First, these regions began with very small memberships in 1950. The conversion of a few thousand individuals thus generated high rates of growth. With much larger base member ships by, say, 1980, per decade growth had already fallen noticeably, even with baptisms numbering in the hundreds of thousands.

Second, the cumulative effects of years of low retention rates in fast growing areas inhibit somewhat the long-term growth and strength of Mormonism. Table 3, based on data not available since 1980, implies the difficulty the church has had, especially in Asia and Latin America, in retaining adult male members long enough to make them Melchizedek priesthood holders.[15] The absence of an adequate priesthood base for staffing wards and stakes eventually limits growth.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 3, see PDF below, p. 19]

Table 4 provides a picture of the changing regional composition of church membership in terms of percentages based on the two series of projections in Table 2. Series 1 figures suggest a redistribution of members that mirrors the one projected in Shumway’s map (see footnote 14). For instance, he predicts that 71 percent of all LDS will live in Latin America by 2020 compared to the Series 1 forecast there of 69 percent.

However, even the more moderate estimates of Series 2 point to the continued erosion of North American dominance. By about the year 2005 Latin America will replace the United States and Canada as the region with the largest LDS population. By 2020 a majority of all church members will reside in Latin America with less than one-fourth in North America, a near reversal of the 1995 pattern in just twenty-five years. In neither of the projections, however, will the church lose its high member ship concentration of 75-80 percent in the western hemisphere. Figure 4 summarizes the shifting distribution of the world’s church members between 1960 and 2020.

[Editor’s Note: For Table 4, see PDF below, p. 20]

As already implied, projections tied to regional trends differ from those for the church as a whole. Regional dynamics generate forecasts which cumulatively project much higher growth rates than those based on the combined population. Thus the cumulative membership size for the Series 1 projections in 2020 comes to 121 million; but if we apply the 1980s churchwide growth rate of 67 percent to the total church population, the number drops to 36.4 million.[16] Here is one case where the whole comprises less than the sum of its parts, producing churchwide estimates that are probably more reliable than those based on variable regional trends.

[Editor’s Note: For Figure 4, see PDF below, p. 21]

The data analyzed above clearly indicate a future of sustained growth for the increasingly international church, but we cannot predict its precise nature with confidence because of our dependence on past patterns of expansion. Better forecasts would require knowledge about the future size of the missionary force and such basic characteristics of members as fertility/mortality rates, sex-age ratios, migration patterns, and activity/retention levels.

Ultimately these variables, combined with the conditions of the chaotic “new world order,” will influence both the number and distribution of Latter-day Saints during the next quarter century. Presumably these factors will also affect the church’s deployment of missionaries and allocation of resources. We can only hint at just how all of this might alter the geography and demography of Mormondom as we continue our global overview to provide a basis for the more specialized essays that follow.

Variables Complicating Growth Projections

Missionary Force

If the Shepherds are correct that the single best predictor of the an nual Mormon conversion rate is the size of the LDS missionary force (see essay herein), then we should consider that factor first. Since 1960 con vert baptisms have increasingly outstripped child baptisms as a source of growth; converts now outnumber born-in-church members each year by a margin of four to one. The number of missionaries increased during the 1980s by about 50 percent, but since 1990 the rate has slowed down (see Shepherds’ Table 1), which might help explain the relative decline in membership growth so far in the 1990s.

The failure of missionary numbers (47,331) to reach the magic mark of 50,000 by the start of 1995 reflects in part a recent tightening in the screening of prospective young missionaries to ensure their worthiness. As President Howard W. Hunter emphasized, “Let us prepare every missionary to go to the temple worthily and to make that experience an even greater highlight than receiving the mission call.”[17]

With the proliferation of new missions everywhere except in insular Oceania, one might expect the church to recruit more older couples for service. Certainly leaders have long encouraged such calls, offering a wide choice of “customized” missions that do not require tracting. Surprisingly few have responded relative to the number of eligible elderly in the slow-growth areas of the church, notably North America. Even though the number of couples more than doubled from 1979 to 1994 (785 to 1,706), the current figure represents on average less than one couple for each stake in the church (or 1.4 per North American stake).[18] Health or financial problems, ties to grandchildren, or a lack of missionary zeal keep many couples from serving.

Since the church still seems reluctant to urge young women (prospective wives and mothers) to fulfill missions, any major increase in the proselyting force must come from couples or from young men. (The current ratio of women to men among single missionaries is about 1:4.) In recent years native residents have comprised more and more of those called to areas outside of Canada and the United States, so that some nations now have high proportions of non-American elders and sisters. However, North America still provides roughly three-fourths of the church’s worldwide cadre—substantially more than its proportion of members (just over one-half).[19] To our knowledge, no one has yet determined if native missionaries propagate the faith more effectively than do non-natives. In any case, the overall annual ratio of converts per missionary has changed little since 1980, fluctuating from 6:1 to 7.5:1.

Public Relations

If LDS leaders cannot find enough willing and worthy missionaries to meet what quotas they set, they can still employ the other means they have developed to spread the gospel message. For example, each year since 1990 the church has produced a satellite broadcast aimed at nonmembers and less-active ones, and it has endeavored more than before to engage faithful members in missionary-related endeavors, including community service projects.[20]

All types of activities, from annual pageants to Temple Square Assembly Hall concerts, function in some way as missionary tools.[21] If anyone wonders why downtown Salt Lake City “probably has the greatest concentration of free tours in the known world,”[22] the answer seems to lie in Mormon determination to promote the message. Such a desire even influenced at least two key members of Salt Lake City’s successful 1995 Olympic bid delegation: (1) a Mormon convert “got involved because I want other people to see the kind of people who live in Salt Lake”; and (2) a lifelong member admitted, “I thought it would be a great thing for the [LDS] church.”[23]

In addition to all of the publicity emanating from Mormondom’s burgeoning Wasatch Front, almost all of the church’s twenty-two areas now have directors of public affairs who try, under the direction of the Area Presidency, to improve the Mormon image with the media, government officials, and local communities. “Public affairs workers are encouraged to recognize opportunities to publicize positive activities and events as sociated with the Church.”[24]

Surely the church has enhanced its image and influence since it first organized a Radio, Publicity, and Mission Literature Committee in the mid-1930s. Appropriately enough, President Hinckley began his career as a defender and diplomat of the faith by serving as executive secretary of that committee. Certainly he would acknowledge that the church’s present Public Affairs Department represents a more sophisticated operation than his original publicity committee, and its programs make it much easier for missionaries and other members to reach and teach possible converts.

Social and Political Conditions

For all its increasing efforts to promulgate Mormonism, the LDS hierarchy still encounters opposition, often strong enough to prevent official entry. “Ten years ago we [leaders] never would have dreamed that we’d have missionaries and congregations in Russia and Latvia and Albania and Mongolia, places of that kind.”[25] Many church members anticipated major breakthroughs in spreading the gospel after the collapse of the So viet Empire in 1989. The church in 1994 had some 8,000 members in that area, where five years earlier it had had almost none. However, Eastern Europe’s and Russia’s current civil wars, economic chaos, and conservative religious backlash have hindered missionary work enough to dampen initial expectations.[26]

The near anarchy not only in Rwanda but in much of Subsaharan Africa could prevent the church from forming many stakes in more than a few new nation-states for decades to come. In 1993, 960 missionaries (almost half of them from Africa) baptized more than 9,000 converts (enough for forty new wards or branches) on a continent that contains about 525 million inhabitants. The church now has authorization for missionary work in about half of the forty-five countries south of the Sahara. However, its limited resources, manifested in the small number of missions (twelve in seven countries) and missionaries (eighty per mission), along with Africa’s political turmoil and cultural pluralism, have seriously restricted the church’s ability to proclaim the gospel there.[27]

As a result, Area leaders have apparently decided to concentrate church growth around the major cities of the countries where the colonial languages of English and French have national recognition. Moreover, missionaries focus on families that have: (1) literacy in one of those two languages, (2) some kind of employment, (3) transportation as well as proximity to an LDS chapel in the growth center; and (4) prospective Melchizedek Priesthood holders.[28] Such a plan should create a widely scattered but highly localized pattern of membership. Since South Africa, with 23,000 of Africa’s 79,000 members (in 1994), rates a temple, we would expect the church to try to erect one somewhere in West Africa—in or near Nigeria or Ghana which together number 34,000.

Compared to East Europe and Africa, Latin America might seem sta ble, but the church has already had enough experience there with terror ism to realize that leaders must proceed cautiously in many countries. For instance, the South America North Area Presidency has responded to such dangers by withdrawing all North American missionaries from Bo livia and Peru and replacing them with Latin Americans. At the same time, however, political and economic instability will apparently not de ter LDS leaders from “working for an explosion [of their own]: more baptisms and more retention [of those baptized].”[29] Such Area leaders, strongly imbued with the evangelizing spirit of their calling as Seventies, still tend to measure success in terms of numbers baptized and retained.

Ironically, in stable places like Singapore the church might have less success than in more volatile countries like Peru and Bolivia. In that prosperous Southeast Asian city-state the Saints have only seven branches and fewer than 2,000 members after more than twenty-five years of activity, largely because of restrictions on proselytizing imposed by the government. Hong Kong, with twice Singapore’s population, has ten times as many LDS (and a temple under construction), probably because more missionaries have operated longer and much more freely there than in Singapore. Relative to its even larger population, Taiwan should have three times as many Saints as Hong Kong instead of only 3,000 more. Local cultural and political variations would probably explain such differences if we understood them.

The church may eye the People’s Republic of China in much the same way that American and European merchants and missionaries long have done: as an enormous marketplace for the goods and the good news of the West (just one percent of the 1.2 billion Chinese would add 12 million members to the LDS fold!). For now, LDS leaders are seeking to establish a foothold on the mainland through cooperative efforts with a Communist regime never noted for friendliness toward religion.[30]

Since at least 1973, when Spencer W. Kimball assumed the prophet’s mantle, the church has aggressively pursued its own “Open Door” policy. It has sought for any opening that would allow it to establish a new mission field. When President Kimball asked David M. Kennedy, the church’s one-time roving international ambassador, “which countries I thought we could open up, I said I would put Portugal first on the list because the people there were undergoing massive change.”[31] After the country’s dictatorship and empire collapsed in 1974-75, LDS elders, many of them from Brazil, entered Portugal. Retornados uprooted from

the former colonies of Angola and Mozambique responded to the missionaries’ preaching more readily than did the native Portuguese. By the late 1980s Portugal not only had four times the membership of the much more populous Spain, but the church’s highest growth rate. Since 1990, however, as Portugal has prospered and integrated its retornados, LDS conversion rates there have leveled off.

By way of contrast, the church struggled for forty years (1950-90) to establish a modest membership base in Paraguay, South America’s poorest and most mestizo state. In just the past five years, however, the number of LDS branches, wards, and stakes has doubled due to a wider dispersion of more missionaries, stronger local leaders, and efforts by both groups to coordinate their conversion campaigns.[32] The cases of Paraguay and Portugal illustrate the difficulty of predicting where and when the church will fare well or poorly, and they also show how quickly trends can change.

Demographic Variations

The present strength of Mormon missionary and public relations programs makes it easy to overlook less visible but more measurable factors that also affect the size of the church from region to region. Among the most important are the so-called demographic variables that constantly shape (and reshape) all populations: fertility, mortality, migration, and— in the case of religions—disaffiliation. Wherever Mormons have more children and live longer than their fellow nationals, the church naturally stands to increase its relative size. However, only in areas with relatively high numbers of lifelong and active members (notably in North America and the South Pacific) are fertility or mortality rates likely to make a significant difference in total numbers. Since 1980 Mormon fertility has declined sharply even in Utah and the rest of the United States, although it remains higher than both national and state averages.[33]

Migration, of course, shapes both the distribution and composition of the LDS population. Nowhere is that more apparent than in the slow growth areas of North America, Europe, and Oceania. The fact that Utah’s percent of U.S. Mormons has dropped by just 6 points since 1970 (from 37.5 to 31.5) reflects more than any other fact the state’s continuing role as the Mecca of Mormondom. Nowhere else have Saints and place bonded so strongly to create a sense of identity. The Pacific Coast states (including Alaska and Hawaii) have increased their share of the national total by only one percentage point during the same period. Between 1990 and 1994 the number of Saints in Utah increased by 120,000 while the number in California dropped by 3,000.

LDS families living outside the Mormon Culture Region sometimes move to Utah (“Zion”) in search of an environment “more supportive of their values.”[34] Those content to live outside the Intermountain West often send their college-age children to BYU or Ricks College (in Rex burg, Idaho), and especially if those children then marry and/or stay in Utah or Idaho, the parents will often retire to the Intermountain West to live closer to their (grand)children. Within the United States, and to a lesser extent Canada, we therefore expect the Far West to retain its preponderance of North “Amer/Can” Saints well into the next century.

Since 1970 LDS missionaries have found newcomers to North Amer ica, Europe, and even Oceania particularly receptive to their message. The United States and Canada now contain more than 300 ethnic wards and branches, at least 40 percent of them in California.[35] Salt Lake City has a Tongan stake, and a stake in Sydney, Australia, has more Polynesian and Latin American members than active Aussies. In Europe 60 per cent of the LDS converts since 1985 consist of immigrants from former colonial empires.[36] Thus migrating members and immigrant converts keep changing the location and ethnic make-up of Latter-day Saints in subtle but significant ways, perhaps especially in areas of slow growth. As immigrants become an increasing component of many well-established LDS communities, how readily will longtime members accept them? Might their presence lead to lower conversion rates among native residents?

The demographic variables combine with the conversion process to create Mormon congregations that also vary greatly in gender and age distribution, ranging from, say, a youthful Cambodian branch in South ern California to a ward of retirees in Salt Lake City.[37] The sex-age structure obviously has some bearing on future growth rates. Two related trends, most evident in regions of rapid growth, naturally concern the leaders of a family-oriented church. First, East Asia (except for South Ko rea), Latin America, and even Europe have only 80-90 males per 100 females (as of 1990).[38] Second, the same areas often draw a majority of their converts from the same age group (15-24) as that represented by most missionaries. A preponderance of young (and often female) single members in, say, Hong Kong or Taiwan, naturally hinders the development of stable family wards.[39] A severe shortage of males anywhere means that many LDS women will marry outside the church, thus increasing the likelihood of their becoming less active.

Paradoxically, rapid growth sooner or later is followed by a slow down if it outstrips the ability of wards with few and/or inexperienced leaders to retain their converts. The decline in the global rate of stake formation over the past decade, as indicated by both Knowlton and the Shepherds (to follow), corresponds with the downward trend in the overall rate of church growth observed for the early 1990s. Leaders of international Areas, when interviewed by Ensign editors, almost invariably mention the challenge of staffing newly created church units. Even in Mexico, where “Many members have been well prepared for leadership” over a relatively long period, “new growth has outstripped the leadership base we have among our longtime members.”[40]

The church has responded to this problem in two ways. First, since 1980 it has established fourteen Missionary Training Centers (MTCs) outside the United States (which has only one, adjoining BYU); half of these are in Latin America. Located near temples, they not only prepare an Area’s native missionaries for proselytizing among their own people, but also provide them with leadership skills they can bring back to their home branches and wards upon their release. Second, and more recently, the First Presidency has instructed mission presidents “to concentrate on teaching fathers and families. There must be a priesthood infrastructure for the Church to have proper . . . leadership,”[41] since ultimately “the Church can grow only as fast as leadership strength allows.”[42]

Challenges of Expansion

Given the above considerations, what kind of church do we envision in the year 2020? Since we no longer have 20/20 eyesight (weakened by years of teaching and writing), we have difficulty peering that far into the future. We can, however dimly, make out a few features. First, we see an institution still headed by an all-male hierarchy of fifteen (the First Presidency and Quorum of Twelve Apostles), the only general authorities exempted from emeritus status. The average age of the top fifteen (now just under seventy) might be considerably higher by then, since many of the current incumbents have a fair chance of living that long. We expect to see from three to six new apostles, with at least one from either Latin America (maybe Mexico), Europe (United Kingdom or Germany), or Asia (Japan or Korea).

The First Presidency in 2020 will preside over no more than about 35 million members. Furthermore, we foresee fewer dramatic shifts in the distribution of Latter-day Saints in the next twenty-five years compared to the past quarter century. The main change, of course, will be a near reversal of the present positions of North America and Latin America on the world map of Mormondom (see Fig. 4, which Table 4 makes graphic). Latin America will loom ever larger than now, with populous Brazil making up for its late (post-1978) start and adding the most members.[43] Yet North America, and mainly the Great Basin Kingdom, will retain its central place as the prime source of decision-making, despite its reduced numerical status. No other area of the world, not even Asia, will match any of the Americas in importance. The church will undoubtedly capitalize on its newly gained acceptance in India and in the countries of the former French Indo-China, but we would be surprised if growth there proceeds much faster than it has among, say, the Thais, who waited nearly twenty five years for their first stake.[44]

We hesitate to predict when and where new temples (or even MTCs) will appear on the map of Mormondom, since “The Lord directs where and when his holy houses are to be built.” In making such decisions the First Presidency takes into account the geography of the membership relative to existing temples but also considers “statements by past and present… leaders regarding future temple locations” and inspects possible sites.[45] Any country with a sizable body of Saints, at least 25-50 thou sand, would seem a potential candidate for a temple, but the church might also decide to locate one in a “forward” position in the huge Area of East Europe and Russia before the membership reaches the usual mini mum of 50-100 thousand. Regardless of where the Brethren decide to site the next generation of temples (at least thirty-five in 2020 to equal the thirty-five completed since 1970), more and more Latter-day Saints will find themselves living within (or moving to) relatively easy access to one of the Lord’s holy houses.

If our projections seem cautious, they reflect the complex dynamics of Mormon expansion that we have identified and illustrated. While the church will continue “to enlarge Zion across the world” and to describe “its achievements … in terms of numbers,” what matters most is the impact of enlargement on the lives of individual members, local/regional units, and even the institution itself. As President Hinckley has advised the membership, “All of our efforts must be dedicated to the development of the individual.”[46] Rapid conversion rates may not serve the best interests of Latter-day Saints at any level if they overtax the church’s resources. Current leaders clearly recognize and seek to meet the challenge of deciding how fast Mormonism can expand and still maintain viable programs for its diverse membership.

Certainly the places and faces of Mormonism will take on an increasingly metropolitan and cosmopolitan cast in the next century, and LDS leaders will preach more sermons on the need for tolerance in an international church. They might also continue to insist that “Our real strength is not so much in our [cultural] diversity but in our spiritual and doctrinal unity … As we move into more and more countries of the world, we find a rich cultural diversity in the Church. Yet everywhere there can be a ‘unity of the faith’ … Temple worship is a perfect example of our unity as Church members.”[47]

Therein lies a second great challenge facing a growing church: striking the right balance between cultural diversity and doctrinal unity. As long as “ethnic Mormons” rooted in the Mormon Culture Region rule the worldwide church, it will retain a built-in American and Utah bias no matter how large and international the membership becomes or how hard leaders strive to discard their own “cultural baggage.” For instance, some French-speaking members still resent the church’s refusal to locate the headquarters of a Quebec mission in the more French capital of Que bec City rather than in Montreal. Even in English-speaking Australia, “The Church is still largely seen as an American church … by public, press, and members.”[48]

Within the United States, Saints outside the Intermountain West often refer to “Utah Mormons” as a group apart, viewing them as somewhat smug, provincial, or simply not sensitive enough to the needs of members living on the periphery—anywhere far from the Wasatch Front. In spite of all the Great Basin members who have learned a second language in distant lands as missionaries, the church has seldom, if ever, promoted bilingualism. Ironically, the only bilingual congregations in Utah belong to other denominations.

Jessie Embry has expressed the church’s “multicultural” dilemma in scriptural language. In the essay that accompanies her map of more than 300 ethnic branches/wards in North America, she points out that LDS general authorities have long vacillated over whether to let “Every man [and woman]. .. hear the fulness of the gospel… in his [or her] own language” or to encourage all converts to become “fellow citizens with the [English-speaking] Saints.”[49] Given the existence of numerous ethnic units throughout North America and Oceania, present church policy seems to support the formation of ethnic congregations wherever logistical considerations seem to require them.[50] Even with a Spanish-and Portuguese-speaking majority among the world’s 35 million Mormons by the year 2020, English, we predict, will still prevail as the only official lan guage of the universal Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

This prediction, like most of those made in this essay, may well prove wrong. The only opinion we can express with confidence is that the next quarter century will bring the church as many changes and surprises as the past one has. However, as a new millennium approaches, perhaps leaders and members alike should discuss more than they heretofore have the causes and consequences of these changes for their lives.

[1] A recent illustration appears in the Deseret News 1995-96 Church Almanac (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1994), 410, which measures “Progress During Administrations of the Presidents” by numbers of stakes and members at the beginning and end of each president’s tenure.

[2] Harold B. Lee, “Growth of Church,” Conference Reports, 6 Apr. 1973 (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1973), 7.

[3] Ensign 25 (Apr 1995): 6, and (May 1995): 52.

[4] Taken from the Wentworth Letter published in Joseph Smith et al., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2d ed., rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1978), 4:540.

[5] Tim B. Heaton, “Vital Statistics,” in Daniel H. Ludlow, ed., Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 4 vols. (New York: Macmillan, 1992), 4:1527. The frequency with which some Mormons move may also result in the church’s inadvertently counting them twice. LDS leaders in Tonga told an anthropologist that their figures included some Saints who had emigrated overseas and presumably become members of record in, say, a California or Utah ward. See Tamar G. Gor don, “Inventing Mormon Identity in Tonga,” Ph.D. diss., University of California at Berkeley, 1988,74.

[6] Heaton.

[7] Special thanks to Nancy S. Rohde and Jim Wanket, former students at Humboldt State University, for drafting the maps and graphs.

[8] For a more detailed description of “The Geographic Dynamics of Mormondom, 1965- 1995,” see the article by Lowell C. “Ben” Bennion in Sunstone, Dec. 1995.

[9] For the definitive mapping of this area, see D. W. Meinig, “The Mormon Culture Region: Strategies and Patterns in the Geography of the American West, 1847-1964,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 55 (June 1964): 191-220; an assessment of his essay and an update of his MCR map appear in Lowell C. Bennion, “Meinig’s ‘Mormon Culture Region’ Revisited,” Historical Geography 24 (1995): 22-33.

[10] The best demonstration of this spread appears in Jan Shipps’s series of three maps showing new buildings erected by the church throughout the U.S., 1950-65, in S. Kent Brown et al., eds., Historical Atlas of Mormonism (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994), Map 78.

[11] See History of the Church, 6:318-19.

[12] Rodney Stark, “The Rise of a New World Faith,” Review of Religious Research 26 (1984): 18-27.

[13] Lawrence A. Young possesses a copy of Stark’s unpublished 1995 paper, “So Far, So Good: A Brief Assessment of Mormon Membership Projections.”

[14] See J. Matthew Shumway’s map-essay in the Historical Atlas of Mormonism, 122-23.

[15] Lawrence A. Young discusses this problem in his chapter “Confronting Turbulent Environments: Issues in the Organizational Growth and Globalization of Mormonism,” in Cornwall, Contemporary Mormonism, 55-59.

[16] The church itself anticipates a membership of 35 million by 2020, assuming “growth rates for the past decade remain constant.” See “Church Notes 1992 Growth,” Ensign 23 (Aug. 1993): 75. Regional projections stem from much smaller base populations than churchwide projections. Small base populations pose problems with respect to forecasting future growth because they exhibit less stable trends. Relatively small institutions committed to high growth can easily sustain it over the short run, but projecting such trends over the long run becomes risky because of the high costs of supporting rapid increases. The same holds true for sub-populations or regions within the organization. As the base populations in the new regions increase, the rate of growth declines. Regional growth rates exceeding 100 percent simply are not sustainable for more than a few decades. Thus projections based on regional trends are unduly influenced by short-term high-growth rates, whereas churchwide forecasts smooth out such effects and result in estimates more conservative but more reliable.

[17] Ensign 24 (Nov. 1994): 8.

[18] According to the director of the Missionary Department, “The growth of the Church has multiplied the need for couples,” but the number of couples serving missions has not kept pace. See Church News, 5 Aug. 1995,3.

[19] Church News, 13 Nov. 1993, 3. A breakdown of missionaries assigned and called by macro-areas would greatly enhance our ability to assess past and future growth patterns, but the church’s Missionary Department declines to release such figures due to the sensitive issue of securing visas for missionaries. Ironically, church publications sometimes include such information for individual areas and countries.

[20] Church News, 11 Feb. 1995,8-10.

[21] Ensign 23 (Sept. 1993): 77.

[22] John Goepel, a travel writer, makes this astute observation in Motorland/CSAA, July/Aug. 1995,34.

[23] Deseret News, 17 June 1995, A2.

[24] Ensign 25 (May 1995): 110.

[25] Church News, 1 July 1995,4.

[26] But not enough to prompt a pullback. Indeed the church has organized that vast realm and its sparse membership into a new Europe East Area, according to the Church News, 1 July 1995,8-9.

[27] This assessment comes from an informative “Conversation with the Africa Area Presidency” in the Ensign 24 (Oct. 1994): 79-80.

[28] A couple returning from the South Africa Cape Town Mission spelled out these criteria in a report presented to the Meadow Ward in the Fillmore, Utah, Stake on July 9,1995.

[29] “Conversation with the South America North Area Presidency,” Ensign 24 (Mar. 1994): 79-80.

[30] For examples of such efforts, see “Conversation with the Asia Area Presidency,” Ensign 25 (June 1995): 76-77.

[31] Quoted by Mark L. Grover, “Migration, Social Change, and Mormonism in Portugal,” Journal of Mormon History, 21 (Spring 1995): 73.

[32] Church News, 27 May 1995, 8-11.

[33] See Heaton.

[34] The phrase comes from Enid Waldholtz, elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Utah in November 1994 and interviewed by the Church News, 18 Jan. 1995,11. Her family moved from San Francisco to Salt Lake City when she was twelve.

[35] See Jessie L. Embry’s fascinating survey of ethnic branches and wards in the U.S. and Canada in the Historical Atlas of Mormonism, 146-47.

[36] Bruce Van Orden, untitled text for his BYU “Religion 344” class on “The Internation al Church,” chap. 9.

[37] For a description of Santa Ana’s Cambodian branch, see Suzanne Lois Kimball, “Cambodian Saints in Southern California,” Ensign 25 (June 1995): 78.

[38] Heaton. R. Larder Britsch, “The Church in Asia,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism, 1:78, points out the anomaly of a male majority among South Korean converts.

[39] “Conversation with the Asia Area Presidency,” Ensign (1995). Of course, to the extent that these young converts pair off and marry, they will eventually contribute families to the church.

[40] “The Church in Mexico,” Ensign 23 (Aug. 1993): 78. Two Dialogue authors foresaw this problem from their own experience in Quebec as early as 1980: Jerald R. Izatt and Dean R. Louder, “Peripheral Mormondom: The Frenetic Frontier,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 13 (Summer 1980): 76-89.

[41] President James E. Faust went so far as to suggest that “We violate eternal principles when we divide families.” Church News, 1 July 1995,5.

[42] “A Conversation with the Brazil Area Presidency,” Ensign, 25 (July 1995): 79. A third response to the problem of providing stronger leadership for “Peripheral Mormondom” appeared in an announcement of new Area authorities. One of their primary duties is to provide leadership training. See Church News, 5 Aug. 1995,3, 7-10.

[43] As of 1995 Brazil claimed nearly 530,000 members (versus 400,000 in 1992). See ibid., 79-80.

[44] Joan Porter Ford and LaRene Porter Grant, “The Gospel Dawning in Thailand,” En sign 25 (Sept. 1995): 48-55; and Michael R. Morris, “India: A Season of Sowing,” Ensign 25 (Aug. 1995): 40-48.

[45] “How are the locations of our temples determined?” Ensign 25 0uty 1995): 66-67.

[46] Ensign 25 (May 1995): 52-53.

[47] This emphasis appears in President James E. Faust’s first address as second counselor in the First Presidency. Ensign 25 (May 1995): 61-63.

[48] For elaboration of these two examples, see Dean R. Louder, “Canadian Mormon Identity and the French Fact,” in The Mormon Presence in Canada (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1990), 302-26, and Marjorie Newton, “‘Almost Like Us’: The American Socialization of Australian Converts,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 24 (Fall 1991): 9-20.

[49] Historical Atlas of Mormonism, 146.

[50] For a discussion of the pros and cons of separating inner-city branches from suburban wards within the U.S., see Sunstone 17 (Dec. 1994): 76-77.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue