Articles/Essays – Volume 20, No. 1

The Veil

Our family had just finished the pre-service reception, and Brother Holbrook, the funeral director, had just closed the doors to the Relief Society room. As Mother’s surviving sisters and their families filed past the coffin for the last time, my own sister took my hand and whispered, “You have to be the one to veil her face, Mary.” Startled, I remembered a scene from twenty years ago when I had joined my husband in bidding farewell to his aunt. We had watched while her eldest daughter placed a yellow rose in the stiffened hands and bent down to lay the temple veil over the beloved face. This was the only time I had seen this ritual.

My brother pronounced a prayer over the coffin that Dad, my brothers, my sisters, and I had chosen a few days before. It turned out to be the least expensive choice and the one that “looked most like Mother” with its brocaded exterior and rose-covered interior. We then had to decide whether or not to leave it open for “viewing.” When the Holbrook family reconstructed her cancer-ravaged face, working from photographs and prosthesis, Dad liked it, so the lid remained up. Her name went up too at the entrance to the mortuary on a small marquee: Lavinia Mitchell Lythgoe. A warm memory brushed my cheek when I first saw it: Her name written on a slip of paper for an eight year-old daughter to keep on her pillow while Mother vacationed for the first time since her marriage. She had aspired to be a painter and a writer. She enjoyed seeing her name in print.

At first I thought it would be excruciatingly difficult to stand beside that reconstructed face while the real one with its delicate, slightly tipped nose and red-headed skin tones looked out from a colored photograph near the guest book. But by the end of the evening, I was able to rest my hand casually on the satin rim of the coffin, even laughing as I reminisced with friends and relatives. The rest of my family seemed relaxed, too, certainly more so than when our ordeal began two days before.

Dennis had arrived from Boston and I from Virginia to stay with Dad and plan the services with Tom and Gaye, who lived in Salt Lake City. On the flight out, I had made up my mind to speak at the funeral even though a nerve ailment had left me with a speech impediment. As eldest child, I challenged the others to do likewise. After some discussion, Tom decided to sing, Dennis to speak, and Gaye to pray. We also chose Rex Curtis, former bishop and husband to my mother’s niece, to deliver one of his fatherly, comforting ser mons, lone Palfreyman, ward organist, would play, and Gaye’s husband, Al, would pronounce the invocation. During this itme, we alternately laughed, argued, cried, and suffered from migraine. (We called it our “group migraine,” a condition we inherited from Mother.) Later, while searching through his personal papers, Tom found a long-forgotten slip of paper on which Mother had dictated the very program we had just created.

We then spent the next few hours in a fruitless search for Mother’s temple clothes. We did find my temple dress, however, the one in which I had taken out my own endowments twenty-six years before. “I wish I could lose enough weight to wear a dress like that,” Mother had said at the time. It pleased me, then, to deliver this dress to the Holbrooks even though it was now much too large to clothe Mother’s wasted body.

Our search had also uncovered the first of a collection of diaries beginning about 1918 and ending a few months before her death. The small red diary of 1928 recounted her courtship and engagement with Dad. As Dennis read it aloud, Dad exclaimed, “Land! Mother had all the men after her!”

“As soon as she met you, Dad,” Dennis told him, “she never could see anyone else.”

The question in all our minds during this emotionally heightened and curiously mirthful period was “How will we get through the program without breaking down?” As the only one in the family to be neglected when musical talent was being passed out, I believed that Tom’s part would be the most grueling. Apparently, he thought so too: After the program went to the printer, he called to say that he had decided to “get it over with” first.

Tom was the one who had watched with Dad during the day and the night of Mother’s leaving. It was he who heard the doctor say, “Let her go. Your Mother has chosen it.” It was he who prayed her through her last agony, he who called the mortuary. Tom’s baritone voice always carries such a wallop, even in a less emotional time, that Dennis, Gaye, and I doubted our ability to follow him.

Dennis and I then decided to type out our remarks and to practice them until we could read them aloud at least once without crying. I chose my words carefully, and although it is not my habit to speak from a prepared text, I now breathed courage from the typed pages.

In spite of our careful plans, however, I was unprepared for the moment when, leaning over the coffin, I heard myself whisper, “I’m sorry, Mother,” and pulled the veil down. I was able to control myself only because my next act had to be mounting the steps to the pulpit.

When I heard Tom’s voice soaring out over the chapel benches, I said to myself, “If Tom can sing, I can speak,” and was able to fulfill the prophecy made by one of my friends: “You will be able to speak. The Holy Ghost has promised to be with those who mourn.”

I spoke of Mother’s inherent joyousness as expressed in her diary: “My birthday! Oh, how wonderful to be alive!” and “Glorious Christmas day! We awoke and found Santa Claus had been.” When, as a child, I had learned that she and Dad were responsible for all the miraculous gifts, she swore me to secrecy and inducted me into the Santa Claus Club. “Santa Claus is real. He lives in the hearts of those who continue to believe in giving.” Santa Claus was a symbol of her delight in all special occasions, in holidays, in visits from friends, relatives, home teachers, and visiting teachers. These visits were faith fully recorded throughout her diaries, ending in late 1979 with the lonely line, “No one came today.”

My eulogy centered around Mother’s search for her mission in life. She had said to me only two years before: “I know I was spared for some mission,” and then, after a wistful pause, “The trouble is I don’t know what that is yet.” After puzzling for some time over this remarkable admission, I had finally decided that Mother had suffered from the same seething ambitions that in form my own life, ambitions completely apart from the lives we live through others. When Gaye recited Mother’s last words to her—”My mission is now over”—I wondered: Had she reviewed her own accomplishments and found them good?

“Like Mother,” I said, “my goals have always been to leave something behind and to take something with me when I go.”

Dennis, a historian, also recreated scenes from her diaries, quoting from an oral history interview he had conducted with Mother and Dad some years before. “Leo and I rode up Parleys Canyon and stopped and talked for a long time. Oh, wonderful! Wonderful! I became engaged!” Then much later, after Dad’s cataract operation: “It was so good to have him home again. I love him so much and after forty-seven-and-a-half years of married life!”

Rex Curtis was satisfying in his evocation of Mother’s devotion to her family and her church, and Gaye’s and Al’s simple prayers made us feel that we had portrayed Mother at her best.

Of course, some questions remained unanswered, even unasked. Why had she allowed her beautiful face to be eaten away by skin cancer, an ailment that, in its early stages, could have been easily cured? During that fifteen-year ordeal, our family had fasted, prayed, remonstrated, and argued until Dad had finally forbidden any more discussion. We watched as she took to her bed in a darkened room, unwilling to look at herself or others, behind a growth the size of a gas mask. It was then that Dennis sent a letter to President Kimball ask ing for advice. President Kimball’s phone call to my mother began a chain of events that finally brought her to the care of a specialist who understood that “your little mother has been afraid of doctors all her life.”

He was right, of course. But I knew the cause was more complicated than that. I knew it could be traced to her ill health as a child when another doctor had advised her mother, “Enjoy her while you can. She won’t live long enough for you to raise her.” Her survival led to a consuming interest in health and illness, to long hours in “health lectures” and much reading in a stack of books dedicated to cures most medical experts would call “quack.” I saw that she might even have become a doctor herself.

During the years when the “sore” was growing, I had felt personally re sponsible. As the eldest, I was sure I could persuade her to seek help. A three day family fast finally allowed me to relinquish my burden. I came to believe that as long as Mother had her wits, she had the right to choose. The life extension granted her may have been the gift that allowed her to declare, “I was saved for some mission.”

When the sun burst out over her gravesite during our last prayer that dark January day, we felt satisfied and we felt that she was satisfied. After being fed by the Relief Society, we went home with Dad to help him prepare for his time alone.

Two days later, with a few women friends at a luncheon, I found myself describing the veiling ceremony. Afterwards, I chided myself for voicing such an intimate experience, and over the next week the memory kept intruding on my cleaning, organizing, and helping Dad with his finances. Dad, Tom, Dennis, Gaye, and I pored over photograph albums Mother had kept for so many years, exclaiming over the hodgepodge collection. Childhood pictures crowded against recent ones in no particular plan. Who was that handsome man with the elaborate sideburns? That lovely lady in the mutton sleeves? Why had Mother kept that unflattering picture of me as a fat teenager, along with an old photo of a boyfriend I can no longer call to mind? It was a treasure hunt and a guessing game.

From albums we moved to drawers, chests, boxes under beds. My old cedar chest, where I had stored my wedding dress, was now filled with yarn and dolls—mine and Gaye’s. Other chests held my red lace prom dress, tatting and crochet from Grandmother’s day, and a wooden pencil box given to me in the first grade as an inheritance from Grandmother. All through the house were boxes filled with letters and junk mail, jewelry, and notebooks. We zipped back and forth in time as if on a crazy amusement ride, sorting, categorizing, seeking significance. Mother’s lifelong habit of never throwing anything away which had always irritated me now seemed a blessing. Most of the treasures of our childhoods were still in the house along with the artifacts of her life that would help us to understand her.

I remember a passage from Eudora Welty’s One Writer’s Beginnings: “It seems to me, writing of my parents now in my seventies, that I see continuities in their lives that weren’t visible to me when they were living” (Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press, 1984, p. 90).

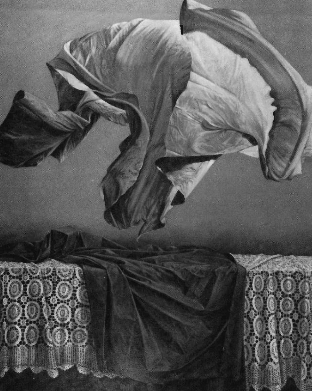

I was sleeping in my mother’s room. As I lay in her bed asking myself why she had chosen to die in such a narrow, uncomfortable berth, I gazed at her walls. A picture of me in wedding finery, a painting of the Great Salt Lake she had painted for my wedding present, a watch I had given her for her fiftieth wedding anniversary. As I gazed at these and other keepsakes, the experience of the veiling continued to hang over my spirit. I had always believed the veiling of a woman’s face to be an insult, harking back to primitive purdah. And yet now other more cheerful images also came: a doll being lifted from a large box through a veil of tissue paper, and later, a smooth floral box revealing long-stemmed roses protected by a veil of moist white paper. How sweet the smell! How romantic the promise! But remembering only seemed to deepen the sting I was feeling.

After going home to Virginia, I tried to write in my diary. But I found myself stopping at the moment of the veiling. For several days I could not write. Then, one day I received a note from Maureen Ursenbach Beecher who had been at the luncheon. “I treasure your sharing the moment of the veiling of your mother’s face,” she wrote. “I would not have thought of that part of our ritual until it came to me, so I appreciate knowing in advance. I kept hearing the Bach music of a similarly beautiful, painful moment: Es druckten Dein lieban Hande/Mir die getreuen Augen zu—the idea that one might go in peace if it were the loved one’s loving hands which pressed the eyelids shut. That office in our family will be my sister’s by seniority and proximity, but it pleases me to know that it will be lovingly done. For moments of anticipated tenderness, Mary, much thanks.”

At that moment my veil of confusion lifted, as if Maureen had actually taken my experience and edited it for me. I knew that when Mother had finally worn out her body and could no longer “face” the loss of her face, she had chosen to give up the struggle, allowing her body to be laid away like an antique doll, too fragile to be disturbed.

As I write this essay, I think of another statement of Welty’s: “Writing fiction has developed in me an abiding respect for the unknown in a human lifetime and a sense of where to look for threads, how to follow, how to connect, find in the thick of the tangle what clear line persists. The strands are all there: to the memory nothing is ever really lost” (p. 90).

So I honor what is unknown about my mother—the essential mystery of her being. I close the lid, and I am thankful.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue