Articles/Essays – Volume 22, No. 1

The Weed

This morning I went to the funeral of a friend who was killed in a motorcycle accident. I slipped into the only vacant pew in the very back of the chapel and listened to the kind and often tearful eulogies. At the front of the chapel the closed casket stood surrounded by beautiful wreaths. A single white rose was placed near the center, a few inches from where my friend’s heart should be. I wept.

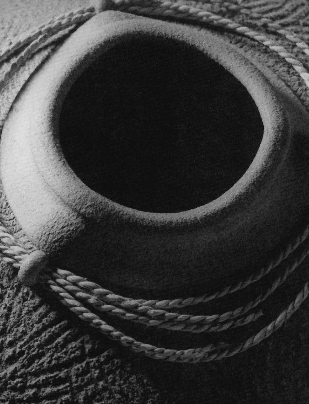

When I returned home, I made a sandwich, though I was in no mood to eat. I could already feel a hypoglycemic headache coming on. I chewed slowly and wondered about death, wondered why it strikes the young and beautiful—the delicate white roses. I wondered too why it seems unable to approach certain individuals, like my grandfather, a gnarled thistle.

I met my grandfather when I was five years old. Late in the summer that year my parents decided to expose our backward southern Utah family to the real world. We went to Disneyland. Almost as an afterthought, my mother called her wayward father in Burbank and arranged a visit. I was immediately apprehensive. From the little I had heard of him, I had concluded my grandfather was an ogre.

Once I had asked my mother why the other children at school had two grandfathers, but I didn’t have any. She brusquely answered that my father’s father had died and her father lived in California. She said he was a very skillful mechanic, but a heavy smoker and drinker; then she made me promise never to smoke or drink.

Later that night when I went to the kitchen for a drink of water I over heard my mother talking in angry tones to my father about the man who had abandoned her family when she was nine. I decided then that my grandfather was an ogre. What else could I assume him to be, when the only beings in habiting my fairy-tale world that were evil enough to run away from their families and smoke were vile creatures resembling school buses (my father frequently told me stories in which grunting, smoke-belching beasts were the villains ). And, because of these stories, I was afraid to meet my grandfather—the ogre. I feared such a beast might shred my body, as the creatures of my father’s stories often did to the unfortunate heroes. And yet, I was almost eager to see him. After all, I had never seen a real ogre before.

When we arrived at my grandfather’s dismal house I was paralyzed with dread. My sisters, both older, stepped from the car and jumped in place. My brother, the oldest, hurried out of the car and up the sidewalk, where a hissing goose stood in the uncut grass. The goose, quick as lightning, flashed its beak to the ground, then lifted it skyward, chortling dark and sadistically. Terrified, I shrank into the corner of the back seat, and after a moment of futile persua sion, my father yanked me from the car and carried me up the sidewalk. As we passed the goose, its head flashed again, and I cringed at the horrifying chortle. The goose was oddly balanced on the back of a large tortoise. My father set me down on the doorstep, then rang the bell. With grotesque fascina tion I turned and watched the goose. Slowly, the tortoise poked its head out and surveyed the ground, apparently looking for its tormentor. The goose beaked the tortoise’s head again, and it snapped back into hiding. Again, the evil chortle. I giggled. And suddenly I knew I would like my grandfather—or at least his brutal goose.

My father rang again, and in a moment a hollow, rusty voice invited us in. My father pushed the door, and we entered.

“Hello,” my mother called into the murky, smoke-filled room.

After a moment’s silence a voice asked us into the living room.

We walked into the dark room, guided by the radiant brightness of the silent TV. I stood by the TV and gazed at the figure in the lounge chair. He was exactly as I had imagined him: fat—tremendously fat—though he didn’t seem to be much taller than my brother. His skin was dark and leathery. Occasionally he would lift a live coal to his lips, then smoke would pour from his nose. I smiled wildly—proud.

“These are your grandchildren,” my mother said as if completing an obligation of the flesh.

“Well, how many are there?” the ogre grunted.

“Four.”

“And how many are you?” the ogre asked, pointing at me.

I didn’t answer for a moment, confused.

My father prodded me. “Go ahead, tell your Grampa how many you are.”

“I’m only one of them. Those are the others,” I said, pointing at my brother and sisters.

Grampa shook his head and pretended not to laugh.

My grandfather was kind to me that day—kinder than he was to my brother and sisters. He gave me a large pocketknife, which my mother took away almost immediately. He taught me to read his marked poker cards. That evening he took our family to a restaurant and insisted that I sit next to him. He ordered for me, then ate half my dinner, making silly jokes as he speared my food with his fork. Jokes like, “Oops, better get that before it falls off.”

That night our family started back to Utah. I slept all that night, but, when I awoke, I heard my mother speaking in hushed tones to my father, as if she were afraid we children would hear. “He must have been drunk,” she said. “He can be a very nice person when he’s a little drunk.” She paused, then continued. “He’s mean when he’s sober and really mean when he’s too drunk.” She seemed angry again, perhaps remembering her childhood.

A few days later, back in Utah, my sisters, no doubt tired of the old school yard chants, invented a new one. They joined hands, as if to dance around a mulberry bush, and chanted, “Our Grampa’s this big . . . Our Grampa’s this big…. ”

I didn’t see my grandfather again for fifteen years, nor did I hear about him. When I was twenty, my mother’s sister received a call from my wealthy great-aunt, Grampa’s sister, asking her to go to California to bring my grand father home to Utah. His neighbors had sent around a petition which a judge honored. Apparently, Grampa had become too filthy and mean to live in Burbank.

I was very surprised that my mother and aunt decided to accept my grand father when he had rejected them forty years earlier. But I quickly realized it was a matter of blood to them.

I was excited to see my grandfather again. Though the memory of my only day with him was very dim, it was one I had held fondly through the years. My family had moved to Provo two years earlier, so it took only minutes to drive to my aunt’s house in American Fork, sixteen miles to the north, to meet Grampa when he arrived.

I was appalled when I saw him. I remembered him as being very large—a jovial man who was kindest to the smallest. But somewhere in the years since I had seen him, he had become scrawny. He had lost an enormous amount of weight, but his skin had not changed size. It hung in loose flabs from his bony limbs like wet wallpaper. But in spite of this tremendous weight loss, he still dressed in the clothes of a very large man.

“Hello, Grampa!” I called out when he was close enough to hear me.

“Hhauw,” he called back.

“How are you feeling?” I asked, amazed at the terrible effect those years had had on his speech.

“Ai’m gluyauw.”

Yes, I thought, you are gluyauw, whatever that is .

My uncle, who was holding his arm, led Grampa into the house. Grampa shuffled as he walked—once on the right, two quick shuffles on the left. My uncle helped him get settled in a comfy chair in the corner of the living room, then Grampa began a hardy effort to vegetate. I sat quietly for a few minutes, waiting for us to become buddies again, or at least wanting Grampa to recognize my attentiveness. But he rarely looked at me, and when he did, he glared. I was confused, but I quickly rationalized that the old man was tired from the move. I should return another day.

At home I realized Grampa and I were no longer buddies. I thought it unfair that the years had made me too old to be a buddy; or perhaps they had made him too old.

I reluctantly returned to my aunt’s house two days later, more out of a sense of obligation than fondness. I found Grampa there, alone in the cherished and well-kept wooded area of my aunt’s yard. He had a bow saw.

“Hello, Grampa,” I said as I approached.

“Hauw.”

“How do you feel?”

“Ai’m gluyauw,” he grunted.

He was feeling much better, I could tell. “Wha’cha doin’?” I asked, trying to imitate his language.

“Ai’m prunn. Ese trees are too bi.”

It was hard to believe he was merely pruning. He was cutting the trunks a few inches below the first fork, so the trees looked like small fence posts. But it quickly became apparent that he was, indeed, pruning. If he were merely cutting down the trees, he would have cut near the base of the trunk, not at the top. He was pruning all right, and doing such a fine job, those trees would never need pruning again.

I watched him. I admired the old man, working hard—slow and steady. Then, with a new grunt I couldn’t understand, he handed me the saw. I understood what he wanted. I threw myself into the work, trying to impress him with my physical abilities. When I had nearly cut through the trunk, he uttered another unintelligible grunt. I ignored it. Suddenly the trunk snapped, swung upward, catching me under the cheekbone, and knocked me to the ground. Grampa shook his head.

“Ai shou’a caserated m’self,” he said. “Ai tol you, ya’ be’er t’tha sie. Some times ese ki’back.”

I smiled, embarrassed by my naivete. I felt something cool running on my cheek. Blood. I started toward the house.

“Whe’you gon’?” Grampa asked, fire in his voice.

“To the house to get a bandage.”

“Ai shou’a caserated m’self,” Grampa said again. “Ge’back ere’n work. We go’a lot a trees.”

Obediently, I returned to the trees and started working, blood dripping.

That evening my mother told me the evil thing the old man had done while her sister was in Salt Lake. She sounded distraught, as if Grampa was already becoming a problem. Suddenly I was secretly proud and happy. Grampa and

I were too old to be buddies, but I felt we were now—accomplices. I didn’t see Grampa again for two weeks. I walked into the kitchen of my aunt’s house one Friday night. Grampa was sitting at the table eating a snack. I sat down.

“Hello, Grampa.”

He didn’t respond.

“Wha’cha doin’?”

He didn’t answer. He ate, spreading dark spicy mustard with his finger onto small slabs of cheese. I helped myself to his cheese, using my finger to spread the mustard.

“Hey, this is pretty good,” I said truthfully.

He didn’t comment. We continued eating in silence, spreading with our fingers. On my third slab I noticed Grampa spreading the mustard a little thicker. I accepted the challenge and spread mine deeper than his. I chewed quickly, then swallowed. Grampa spread thicker yet and ate, chewing slowly. He seemed to relish the battle, as if expressing his anger over losing his freedom. I quickly grabbed another slab and spread the deepest yet, trying to say his confinement wasn’t my fault and that I resented having only one memory of a grandfather while growing up. After a moment of this, my mouth began to burn as if hell had lodged itself under my tongue. I got up and poured two glasses of water. I had lost the battle.

In a moment I began to eat again, spreading lightly. We ate in silence. Soon my aunt walked into the kitchen, watched us for a moment, then chuckled.

“I see you two take after each other,” she said.

I smiled uneasily at her; Grampa didn’t respond.

She left, and we continued eating. Grampa finally took a sip from his glass.

“I’m going back to college in a couple of weeks,” I said.

He ignored me.

Frustrated, I finished eating and left.

I didn’t see Grampa again before I left for college. I was mad at him for not accepting me—for barely acknowledging my presence. I was mad at him because he didn’t treat me like an accomplice. I knew I was nothing to him.

I didn’t see him, but I heard a story about him. Apparently, Grampa decided to cut the trees we felled into logs for the fireplace. With my uncle’s circular saw he cut the branches off the trunks, then held the trunks on his lap and cut them into small lengths. He cut seven or eight pieces before he cut into his leg. The wound was deep and bled profusely. He hurried to the house for help, but no one was home. In the garage he found rags to stop the bleeding. Then, with the logic of a derelict, he straightened a fishing hook and sewed his leg with line. Later, my aunt came home and took him to the hospital. Though I laughed when I heard this story, I was embarrassed by it.

Two days later I left for Southern Utah State College in Cedar City, my hometown. I liked college life, but the hours of homework bored me. Occasionally, my mother would mail me a cassette-letter with stories about Grampa.

On the first tape she told how my rich great-aunt had bought a house in Orem for my grandfather. My mother’s brother moved into the house with his family to take care of Grampa, who lived in an apartment built into the garage. Grampa seemed happy there, living alone and independent. He took to stealing shopping carts. He wasn’t stealing them simply to make trouble, like a juvenile delinquent; he stole them to fill a need produced by old age and to make trouble, like a senile delinquent. His particular need was to carry imported beer and other groceries from the liquor store. For Grampa, with cane in one hand and a shuffling, unsteady gait, carrying objects was impossible. He filled a shopping cart, then pushed it home, leaning heavily upon it. He carried his cane in the basket for dogs or for side trips. Stealing carts worked very well for Grampa, and when the police finally arrived at his house, he was on the street with a full cart and had three other carts in the yard.

The police were very kind. They made him return the three idle carts and buy the fourth. Two weeks later the same officers returned with a blaze orange stocking cap. They gave it to Grampa and ordered him to wear it while on the streets with his cart so that drivers could see him.

The tape ended abruptly, and I didn’t hear the rest of the story. Of course, I hid the tape, embarrassed.

A month went by before I received another cassette. The story it contained was a wonderful diversion from my heavy load of undone homework.

My mother said early one Saturday morning she received a call from a boyish-sounding BYU student. He said Grampa was at Utah Lake Park where the road crossed the Provo River. I knew the place well; several times I had gone there to feed the ducks crusts of bread. It was about two hours shuffling distance from Grampa’s home. The kid asked my mother to hurry, saying Grampa had fallen in the river and he had jumped in to save him. They were both very cold, and he was worried about the old man. My mother hurried to the river and found Grampa sitting on a log, acting like a wet cat, muttering quietly and shivering. The student’s date was there, standing as far away from Grampa and as close to her date as she could.

“You should keep better watch on your father,” the kid said as my mother got out of the car.

“We can’t control him,” my mother answered, trying to sound reproachful. “Come on,” she said to Grampa, “get in the car, and let’s go home.”

Grampa obediently shuffed to the car, leaning heavily on his cane, and got in. My mother opened the trunk and wheeled Grampa’s cart over to take it home. The kid helped her load it and its contents—four six-packs and several fifths. My mother thanked the kid, got into the car, and drove away. Grampa told her what had happened.

My mother said: “Your grandfather told me, ‘I stopped to watch the ducks. I miss my ducks. I guess I lost my balance. I grabbed my cart, then all of us went in. I got my cane to get out, but I kept falling. Then, this fool jumps in—trying to be a hero. The damn fool. He jumps in and pulls me out. So, I hit him with my cane and made him go back for the cart. Son of a bitch, he lost a fifth of rum. The son of a bitch.’ ” She hesitated when she quoted his cussing.

A roommate in the next room overheard the tape and started laughing hysterically. He came into my bedroom and asked me if the story was true. I told him it was, and he said, “I wish my grandfather was like that. My grandfather just sits around in a rest home and drools.” He left my room laughing, and suddenly I was very proud of Grampa. I reminded myself we were kind of like accomplices.

I received another tape the week before mid-terms. I was very anxious about the tests, but I was too far behind for studying to help, so I listened to the tape a few times instead.

My mother said: “About a week after I sent the last tape, Daddy got arrested by the Orem police for pruning the trees along the sidewalk by his house. And you know how he prunes trees. Anyway, he went back to California before his court date. When he came back, the seasons had changed, and the leaves had started falling. When Daddy went into the courtroom he told them the trees were dying and it wasn’t his fault, because he had gone to California and couldn’t take care of them. The judge laughed, then showed Daddy a petition his neighbors had signed. He ordered him to go to the mental hospital for a psychological evaluation. He said he had to stay there three months.”

My mother said on his first day there, he went into a doctor’s office, and the doctor said, “Mr. Stewart, do you know what my name is?”

Grampa said, “Well, you dumb son of a bitch, if you don’t know your own name, I’m not going to tell you.”

My mother said Grampa almost immediately turned the rec-room into a pool hall. It started out innocently. Grampa played nine-ball at a dime a point. He allowed himself to lose a few times but never lost more than sixty cents. He frequently won upwards of a dollar fifty. Then he turned to seven ball at a dollar a point. He often won over twelve dollars per game. The other patients began to refuse to pay their debts, so Grampa recruited a big man to collect. The big man was spending the last six months of his prison sentence in the hospital to get off drugs. After he broke one nose, the other patients paid off quickly.

The story was not as funny as others my mother had told, but I listened several times, trying to distract myself. It didn’t work. All I could think of were the examinations and what a fool I had been for not consistently doing the homework that would prepare me for them. I admitted to myself that I was a fool who played around too much—probably like my grandfather when he was young. It occurred to me then that college was no place for me and most likely never would be. I probably would never be responsible enough to do homework.

The next morning I left Cedar City and moved back to Provo where I got a job in a gas station. I was very happy there, making trouble when I could.

The mental hospital sent Grampa to a nursing home in Springville, which my great-aunt agreed to pay for. She also agreed to send him a few hundred dollars a month for pocket money.

Grampa was disagreeable there. He frequently flushed washcloths down the toilet, trying to back things up. He succeeded a few times. When the staff started hiding the cloths, Grampa resorted to more creative ways of entertaining himself. He bought a basket of juicy red apples and gave them to his mates. When one polite old gentleman refused an apple, saying he had no teeth, Grampa called him a yellow son of a bitch. Then he added, “Hell, I’ve only got two.” The gentleman finally accepted the gift, and Grampa grinned evillv as the old duck sucked on the skin.

Things soon quieted down with Grampa. The staff of the nursing home began to accept his eccentricities and quit reporting his bad behavior to us on a weekly basis. The only times I saw Grampa were on holidays or on his birthday. My mother would send me to the nursing home to bring him home to dinner. I noticed on the first of these infrequent visits that Grampa had modified his shopping cart. He had cut off the top half of the wire basket to ease loading and unloading. He had rewrapped the handlebar to make it larger and easier to grasp. He had replaced the rear wheels with the big wheels and the axle of a baby carriage. The cart now rode more smoothly and was easier for Grampa to push. His skill as a mechanic was evident.

I also noticed that Grampa’s shuffle had become much slower and weaker. His speech had deteriorated even more. I realized Grampa would soon die. I resigned myself to thinking I would soon be without a grandfather, like when I was a kid. It was easy to think this; I had survived most of my life without him, and I knew I would continue to survive when he was gone. Even during the time I had known him, I was only one person—alone in all my battles. It was easy to think—but sad.

At the end of dinner that first night, Grampa and I were the only ones who asked for mince pie for dessert. I remembered that night with the mustard and cheese. I remembered that my aunt said Grampa and I took after each other. I realized at that dinner that I did fight all my battles alone, but I was more than one—I was two. And suddenly, thinking I would soon be one again became tragically painful. My father drove Grampa home that night.

Six months later Grampa became a problem again. He had taken to hiding the false limbs of the amputees among his mates and to starting fires. The home decided he was dangerous and kicked him out. I was very happy—very proud. I began to hope I would be two for a long time.

At the next holiday I picked Grampa up at a motel across the street from the home. His shuffle was still slow and weak, his speech still difficult. Innocently, I asked if he missed the nursing home. His speech was difficult, but his answer was not.

“Tha fuckin’ place?” he said.

I brought him to my home for dinner, and I enjoyed his company, though we never spoke. I took him back to his motel that evening. We didn’t say good-bye after I helped him to the door of his room, but I think he knew I meant to say it. And I think he meant to say it too.

Another six months went by, and Grampa again became a problem. And again, I was proud. The manager of Grampa’s motel called my mother and said Grampa was too filthy to keep. He was to be evicted the next Friday.

Wednesday evening my father and I went to clean Grampa’s room in preparation for the move to another motel. The room was as we expected—squalid—but I admired it. My father and I collected Grampa’s dirty clothes and soiled sheets to wash. As my father picked one pair of overalls off the floor, he shook them gently. They didn’t bend. We both laughed.

I carried two five-gallon buckets to the laundromat and filled three ma chines, putting extra soap in each. I dried and folded the clothes, then went back to Grampa’s room.

My father had finished most of the cleaning, but there were still various types of wire lying about the room. Though he didn’t need the money, Grampa collected wire and occasionally sold it to recyclers for a few pennies. My father and I quickly finished the room, then offered to help Grampa to his new motel. Grampa nodded. Friday morning, he said, as if that was the time he wanted our help. I had to work Friday morning, but my father said he would be there. He went out to the car and got in.

As I passed Grampa on my way to the car, he said quickly, “Ese trees are too bi. Le’s prun toni’.”

“Yeah,” I said, grinning evilly, “they are too big.” I walked to the car, trying to subdue my grin. I was wildly proud. I was an accomplice.

I came back later that night, about 2:00 A.M., and the old man, he was waiting.

I returned home from the funeral of my beautiful friend—the white rose— and I wondered about death. I wondered why it strikes the young and beautiful—the delicate flowers. And I wondered why it seems unable to approach certain individuals, like my grandfather—a gnarled thistle. A thought occurred to me then: Weeds are always the last to die. I repeated the thought aloud and took comfort in it, assured of my own immortality.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue