Articles/Essays – Volume 11, No. 1

Thomas F. O’Dea on the Mormons: Retrospect and Assessment

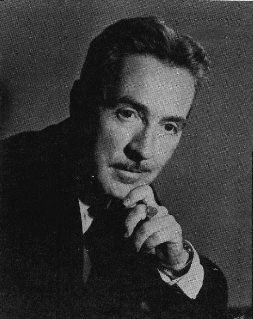

I first encountered Thomas F. O’Dea through his book The Mormons which I read with considerable excitement. Here, it seemed to me, was a person professionally concerned with the development and enhancement of the scholarly study of religion, who had written a superb example of the art and science of religious studies. I wrote to O’Dea, conveying my excitement and appreciation. After the manner of pedantic (or meticulous) scholarship, I also called his attention to a misstatement of fact on page 225. He had reported that the University of Utah, founded in 1850 was “the oldest university West of the Mississippi.” As Director of the School of Religion at the University of Iowa, I knew that a) Iowa City is west of the Mississippi, and b) the University of Iowa was founded in 1847. (The University of Missouri, I learned then, was founded in 1839.)

O’Dea received my letter cordially enough, and we later came to know each other fairly well. I always had the feeling though, that he, as a close student of Max Weber had been impressed with my obvious attention to neatness, and regarded me as something of a latter-day ascetic. Nevertheless, or perhaps even because of that, we did develop a mutual respect and, I believe, fondness for each other.

After coming to the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1965 to become Chairman of the newly created Department of Religious Studies, I was able to help persuade O’Dea to come to Santa Barbara as Professor of Religious Studies and Sociology, and Director of the newly founded Institute of Religious Studies. There we worked together closely from 1967 until his untimely death in November of 1974. The eulogy which I prepared at the time of his death was printed in part in a letter to the editor by M. Gerald Bradford, Dialogue, Vol. IX (Summer, 1974).

Thomas O’Dea was a complex person. He lived on what Paul Tillich called the boundary line—not only between science and religion but also between doubt and faith, loneliness and fellowship, alienation and reconciliation, despair and hope, and, as he might have put it, between time and eternity, life “here below” and transcendence. He was born into a Catholic home in Amsbury, Massachusetts. His father had emigrated from Ireland as a young man, and his mother was a second generation American of Irish descent. Thomas attended parochial school through the eighth grade. In school, church and home he was exposed to an intense form of Irish Catholic piety which left its permanent mark upon him. Throughout his life he maintained an ambivalent relationship with the Roman Catholic Church and the communal life which it nourishes.

A skilled psychohistorian might suggest as one point of departure in “explaining” Thomas O’Dea his own account of his father’s reaction to a grammar school report card which showed that he had received A’s on all but one or two subjects. The father offered not praise but a question, “What happened in those subjects?” It is clear that O’Dea was imbued early in life with an intense drive toward excellence. That drive manifested itself both in his unquenchable thirst for knowledge and in his often painful but persistent pursuit of holiness. I use that word not in a moral but in a religious or even mystical sense. O’Dea exemplified the truth of St. Augustine’s confession to God that “our souls are restless until they find rest in Thee.” He sought but apparently did not find that rest in this life, and restless indeed his life was.

In this article I attempt to treat O’Dea’s “Mormon” work on two levels: its reception by the Mormons and some of its contributions to our understanding of the Mormon movement. I have focussed on two subjects of central concern to O’Dea: the sociological classification of Mormonism as a religious movement and the complex interrelationship between Mormonism and the American ethos.

Secondarily, I suggest points at which some understanding of O’Dea’s complex personal history might help us to understand his work. What was the underlying drive, the basic and perhaps partially hidden agenda in his study of the Mormons? The attempt to answer that question requires a more subtle inquiry than this description involves. Yet I think it is worth trying because it seems to throw light on O’Dea’s work and especially on his assessment of Mormon strengths and weaknesses. But such subtle inquiry is obviously prone to presumption and error, and I apologize in advance if, unknown to me, either or both of these are evident in the article.

The immediate stimulus for an examination of the subject of this article was an invitation to participate in a symposium on “Institutionalization, Adaptation, and Change in Religious Systems: The Work of Thomas O’Dea” at the annual convention of the Association for the Sociology of Religion in August of 1976. That led me into a review of O’Dea’s published work on the Mormons and an initial investigation of his unpublished materials on the same subject. The latter, consisting of O’Dea’s field notes made during his intensive study of Mormon culture in 1950, a manuscript on “Mormon Values,” and some miscellaneous materials, are now a part of the Thomas F. O’Dea Collection in the Harold B. Lee Library of Brigham Young University. That collection, which also includes materials on other subjects that O’Dea studied, will soon be available for use by scholars. A revised version of the paper I presented at the O’Dea symposium will be published soon, along with others presented at the symposium, in Sociological Analysis. While there is overlap between the two papers, the foci and development are quite different. RSM.

***

The Mormons, published twenty years ago, was received with almost universal acclaim.[1] Perhaps most striking about reactions to the book was the high praise accorded it by scholars of Mormon background. Kimball Young called it “the best account and interpretation at hand.”[2] Sterling M. McMurrin found it to be “easily the best general statement yet published on the Mormons.”[3] And Lowry Nelson concluded that it was “without peer as an overall study of the Mormon movement from the standpoint of the social analyst.”[4]

In the context of the scholarly study of religion in America, the most remarkable thing about The Mormons was that it was something new. Here was a comprehensive study by a social scientist who was not a Mormon but who regarded his subject with considered seriousness and who endeavored to understand on its own ground as a religious movement.

It is obvious to any reader of The Mormons that Professor O’Dea had done his homework. That included academic preparation in Harvard University’s Department of Social Relations where, as a veteran of World War II, he wrote a brilliant undergraduate thesis on an ultraorthodox Catholic center in Cambridge. Graduating summa cum laude from Harvard, he was accepted into the graduate program in Social Relations. One of his early assignments as a graduate student was to prepare a library study of “Mormon values.” This study was to be used as background material for a field study of a Mormon community in New Mexico, a community considered to be representative of one of the “five cultures” of that area which were being studied under Harvard auspices.[5] While O’Dea had not originally been chosen to do the field study, his paper on “Mormon values” was so well done that he was selected for that job. Instead of going directly to New Mexico, however, he and Mrs. O’Dea proceeded to Salt Lake City—the obvious center of his subject. There, during the late summer and early fall of 1950, he interviewed several Mormon scholars and churchmen[6] and also delved more deeply into written sources on Mormon history and doctrine. Then he and Mrs. O’Dea moved to Ramah, New Mexico, where they spent the next several months relating as closely as possible to the life of that community.

Out of this combined library and field study, Professor O’Dea produced a more than five-hundred page doctoral dissertation entitled “Mormon Values: The Significance of a Religious Outlook for Social Action;” four brief but insightful articles on various aspects of “the sociology of Mormonism;” a sizeable manuscript on “Mormon values” which is a revision and enlargment of his doctoral dissertation; and the book The Mormons.

Professor O’Dea’s work on the Mormons not only shows evidence of in depth homework; it also reveals the scholar to have been a man of remarkable powers of empathy and perception. He was the first non-Mormon scholar to attempt a serious and extended historical-literary treatment of the Book of Mormon. He was the first non-Mormon intellectual to examine sensitively sources of strain and conflict within the movement. And finally he was a social scientist who recognized early that there was no way his subject could be adequately handled within the confines of a narrowly conceived or sharply delimited scientific methodology. Rather it required a careful and extensive use of the tools and insights of the anthropologist, sociologist, historian, philosopher, theologian and literary scholar. In other words, O’Dea refused to succumb to that common temptation among social scientists to convert rich historical detail into preconceived and bland generalizations.

O’Dea’s work on the Mormons has worn well. A review of past issues of Dialogue indicates some thirty citations to works by O’Dea, all of them favorable and some highly laudatory. Among these is an assessment by the scholar who is now Church Historian, Leonard Arrington. Writing in 1966, Arrington stated that O’Dea’s works “offer unquestionably the best ‘outside’ view of Mormon thought and practice now available.”[7] The Mormons was published in paperback in 1964, and the current clothbound edition carries the line, “Eighth impression, 1975.” The book continues to be cited by Mormon and non-Mormon scholars alike, and it is still one of the best comprehensive studies of the subject.

O’Dea’s work is a model for the scholarly study of a religious movement. By that I mean—to reiterate—that O’Dea sought to understand the Mormons by concentrating initially on their common life as a religious people—their doctrines, their own self-understanding, and the details of their history—rather than relying on external categories and assessments to understand them. Theory and method must always be in reciprocal relationship with data if they are to lead to understanding.[8] O’Dea’s work sets a standard which has not always been followed even by the most reputable scholars. And in assessing Mormon strengths and weaknesses, his own existential and critical concerns surfaced.

Classification

Two issues illustrate O’Dea’s attempt to forge theory, method and data into a better understanding of Mormonism: 1) the question of the classification or the typing of Mormonism as a religious movement; and 2) the ambivalent relationship between Mormonism and the American ethos. Both issues were central to O’Dea’s concerns. Both continue to attract the attention of scholars.

In his massive A Religious History of the American People, Professor Sidney E. Ahlstrom of Yale University confesses his puzzlement over the question: “One cannot even be sure if the object of our consideration is a sect, a mystery cult, a new religion, a church, a people, a nation, or an American subculture.”[9] At the same time, he describes this movement variously as the most noteworthy of the American contributions to world religions, “an important American subculture,” and “a vital episode in American history.” And he concludes that, when interpreted in detail, Mormonism “yields innumerable clues to the religious and social consciousness of the American people.”[10] Ahlstrom’s “answer” is that at “different times and different places” Mormonism was all of the types he listed[11]—may be taken as a quick summary survey of social scientific efforts at classification.

Several scholars have attempted to squeeze Mormonism in under Ernst Troeltsch’s not so capacious church-sect umbrella. The most common designation used for Mormonism by these taxonomists is “sect.” Yet, standing alone, that designation has seemed inadequate, and various modifiers have been advocated—such as, “established,”[12] “cultic,”[13] “many-sided,” and “churchly-worldly.”[14] Some have described Mormonism in terms of what has come to be understood as a typical evolution from “sect” to “denomination.”[15] Other typologists have concluded, however, that Mormonism cannot be confined within the church-sect-denomination scheme at all, and they have suggested other categories instead, such as “independent group,”[16] “ethnic group,”[17] and “nationality.”[18]

O’Dea himself gave a great deal of thought to the question of classification. He concluded in his doctoral dissertation that the Mormon movement “is not another of the sects of which America had so many. Nor is it a church in the older historic sense of European Christianity.” Perhaps the common practice among Mormons of referring to themselves as “the Mormon people” offered a useful clue to the question. Here is a hint that, sociologically and typologically, the Mormons might be better understood in reference to ancient Judaism or early Islam than in the context of early Christianity, which was Troeltsch’s primary point of reference in his church-sect distinction. According to O’Dea, the Mormons developed “from a small body of believers to the bearers of a particular culture identified with a geographical area and a political entity,” from ” ‘near-sect’ to ’empire.'”[19] This last, succinct description in the doctoral dissertation was changed by O’Dea to “from ‘near-sect’ to ‘near-nation’ ” in his first published treatment of this subject.[20] More than a decade later he used the same description but without the quotation marks—an indication, perhaps, of his increased confidence in its aptness.[21]

Mormonism and the American Ethos

In his most detailed analysis of classification, O’Dea listed ten reasons why Mormonism avoided “sectarian stagnation.” The first he described as “the nonsectarian possibilities of building the kingdom which could require so much of subtle accommodation.”[22] I suggest that this is probably the most important factor indigenous to the movement itself, and I want to use this statement as a text for shifting focus from the question of classification to the question of Mormonism and the American ethos.

Mormonism, both in its kingdom building drive and in its “subtle accommodation” not only avoided “sectarian stagnation” but also displayed a complex and fertile symbiotic relation with the American ethos. The early Mormons identified with certain classical American notions. As O’Dea suggested, they “resacralized” much in American thought that had become secularized.[23] And in the end they bound sacred and secular so close together that the dividing line between them all but disappeared. Human endeavor in America became a sacred and eternal reality, a matter of “eternal progression.” By understanding the human enterprise in America principally as an effort to build the kingdom of God on earth (the new order for all ages.) Mormonism presented “a distillation of what is peculiarly American in America.”[24]

From Mormon history I want to pick one item to illustrate the points made thus far, Joseph Smith’s announced candidacy for the office of President of the United States in 1884. How shall one understand that event? Ahlstrom, in a fleeting reference, treats it as additional evidence of Smith’s “megalomania.”[25] That same word is used by one of Smith’s most controversial biographers, Fawn Brodie, who relies heavily on psychiatric concepts to account for this enigmatic figure.[26] If one wishes to do so he can muster a fairly impressive array of data to sustain such a usage, as, in fact, Brodie does.[27] Nevertheless, it does not seem particularly imaginative on the part of a scholar of religious history—such as Ahlstrom—to resort solely to the psychiatric lexicon to deal with Smith’s candidacy. If one views Mormonism as a religious movement and its founder as a religious figure (which Ahlstrom certainly does although Brodie apparently does not[28]) then one might more consistently seek for some insight from the phenomenology of religion in general and from the religiously fertile soil of early nineteenth century America in particular.

Smith’s announced candidacy ought to be seen in the context of his evolving and complex understanding of human endeavor in this world and more specifically, of his own peculiar brand of millenialism. Smith was a premillenialist, but he believed that the restoration of the gospel and the building of the earthly kingdom of God must preceed the return of Jesus Christ. His announced candidacy and his institution of what came to be called the “Council of Fifty” can be understood as steps in the kingdom building process.[29]

In dealing with Smith’s announcement one would also do well to look more closely at his grasp and use of the political realities of his situation. There was a practical side to his candidacy—a side which illustrates O’Dea’s point about “subtle accommodation.” Even Brodie reports that Smith “suffered from no illusions about his chances of winning. … ” He wanted to win publicity for himself and his church, and, of more immediate consequence, he wanted “to shock the other candidates into some measure of respect” for the Mormon people and their cause.[30]

By 1844 Smith had maneuvered Nauvoo into being an almost independent city-state with its own unique charter, court system, and military force.[31] Although he displayed lack of political realism at certain critical points in his life, he was well aware of the potential power in Illinois politics of the votes of the largest city in that state, and he exploited that power to gain this worldly ends. Buoyed by the attention Illinois politicians paid to him, by the almost daily arrival of new converts and by an almost constant flow of good news from missionaries abroad, Smith had some reason to hope that the political power of his kingdom might soon envelop Illinois and perhaps even the whole nation. At the same time, however, he was painfully aware that, to put it mildly, he and his people were not universally regarded with admiration by their “gentile” fellow Americans. While he was busily building the kingdom in Nauvoo and hoping that it might expand eastward, he was also directing fairly extensive negotiations and explorations for a settlement in the West where the political kingdom of God might be established anew without undue external resistance.

Following Smith’s martyrdom, the main body of Mormons, under the able leadership of Brigham Young, moved into one of those designated areas of the West and there sought to build or rebuild the kingdom. Kingdom building and “subtle accommodation” continued side by side.[32] Both were characteristically Mormon and characteristically American.

Emerson aptly called Mormonism “an afterclap of Puritanism.”[33] The similarities are striking (as are the differences too, of course). Each movement displayed elements of both sectarian exclusiveness and churchly inclusivenessand accommodation. Each made extensive truth-claims, was vigorously activistic, and each engaged in concerted efforts over extended periods of time to build religious commonwealths. Both were strongly communal in their approach to most aspects of life, including the political and the economic. Each sustained an ambivalent relationship with its “mother country”; and, in the end, each had to succumb to the realities of religious pluralism and of the secularization of culture. Yet Puritanism became the most significant movement in the shaping of the American nation, and Mormonism, the only religious movement in national history to be able to work out, over a significant period of time, the ideal of a religiously suffused commonwealth, became a “near-nation” itself.

Legally, in the Utah territory, or Deseret, the Mormons came very near to establishing an independent nation. They became, not only through political means but even more obviously in various economic endeavors and in countless other ways, a semi-independent religious subculture. As they underwent “Americanization” for statehood, however, the Mormons were forced to relinquish their formal commitment to the establishment of the political kingdom of God on earth. The most obvious symbol of their loss of independence was the abandonment of plural marriage under threat from the federal government of corporate disfranchisement. This act signaled the final abandonment of formal commitment to the establishment of the political kingdom of God. In actuality, the notion of the kingdom of God as a political reality separate from the Church gradually had become, under steady federal pressure, identified with the Church itself. In the process, the idea of the kingdom became less and less political and more and more spiritual.[34]

Did formal abandonment of political kingdom building signal a decline into “sectarian stagnation” or an evolution into cultic mystification? Or has Mormonism managed to direct the kingdom building drive into other channels in such a way as to maintain its vitality as a culture-shaping religious movement? While the establishment of a political kingdom of God was indefinitely postponed, the effort to master this world was not. Kingdom building, no longer a formal political goal, went on nevertheless in the intensity of daily life at work and at play, in the family and in the community.[35] This pervasive drive toward what O’Dea called “the transcendentalism of achievement”[36] generated a continuous flow of energy.

Mormon Strengths and Weaknesses

The question is, how can this continuing Mormon dynamism be assessed: 1) in the light of early Mormon intention to build the kingdom of God, and 2) in the context of the present-day world? The metaphor of building suggests putting constituent parts together in some ordered fashion. It also suggests that the existing structure is inadequate or incomplete and that the materials are at hand either to remodel or to build anew. One is dealing here with what is, as against what can or ought to be—in ordinary language, with the real and the ideal. Perhaps Mormon vitality today can best be examined on the boundary line between these two.

Thomas O’Dea discovered among the Mormons an aspect of American life that was new to him and that he found to be challenging and even exhilarating. The hardiness of Mormon family and community life impressed him. And this wholesome vitality might, at one time at least, have given him renewed reason for cautious hope in American vitality. But he also discerned problems within Mormonism, problems whose sources were to be found both within the movement itself and in its relationship to the modern world. He saw “strain and conflict” as stemming primarily from a view of the world in which the dividing line between the real and the ideal had too easily been erased. Philosophically, what O’Dea called Mormon “literalism in theology” precluded the possibility of analogy.[37] The failure to distinguish between “the natural and the historic elements” of belief, on the one hand, and “the supernatural and transcendent elements,” on the other, meant that “it has been impossible for a middle position to emerge between literalism and liberalism.”[38] O’Dea saw this as the root cause of what he described as “Mormonism’s greatest and most significant problem—its encounter with modern secular thought.”[39] This problem became especially evident to Mormon intellectuals—some of whom constituted O’Dea’s “data base” for his examination of the “sources of strain and conflict” within the movement. In fact, one might even suggest that it is a problem which surfaced only among intellectuals although O’Dea saw it as being of great importance within and to Mormonism generally.[40]

Religiously, O’Dea saw that what he regarded as a premature closure of the gap between the real and the ideal—or between God and the world and between God and man—prevented the development within Mormonism of either a sacramental or a contemplative approach to life.[41] What emerged instead was a highly verbal and activistic approach. The great stress on activism, especially when conjoined with a coalescing of the ideal and the real, the sacred and the secular, has meant, in recent times particularly, a tendency to exalt things as they are, to appear to condone “activity for activity’s sake,” and hence an inclination toward social and political conservatism. And for O’Dea this raised the critical problem of relevance in the modern world, a world which he understood to pose not only a serious challenge to faith but also a challenge to our basic understanding of what it means to be human.

Thomas O’Dea had a special capacity to see polarities in human experience. He dealt extensively in his work with crises, strains, tensions, conflicts and dilemmas.[42] Furthermore, as a son of both the Enlightenment and Roman Catholic spirituality, as both an intellectual and a man whose soul was restless until it found rest in God, he lived in an almost constant state of tension himself.

Some human beings neither experience nor discern the same sorts of tension, strain, and conflict that O’Dea did. William James noted that alongside the tortured “twice-born” soul there is the “healthy-minded,” “once-born” religious type. For such a person, religion involved “from the outset . . . union with the divine.” The gap between the real and the ideal is thus either closed from the beginning or does not exist at all, and one’s personal “happiness is congenital and irreclaimable.”[43]

James ventured the suggestion that the “theory of evolution” was helping to lay the foundation for a “new sort of religion” which the “once-born” type found to be especially appealing.[44] Sociologist Robert N. Bellah has argued for the emergence of a kind of religion, or a stage in the evolution of religion, which bears similarities to the phenomenon which James described. Bellah called this “modern religion,” and he characterized it as a “collapse of dualism” and a stress on continual individual self-transformation or self realization.[45][46] James’s “once-born” type would be quite at home in Bellah’s “modern religion.”

Anthropologists Mark P. Leone and Janet L. Dolgin have recently argued, on the basis of their field studies, that Mormonism has become a “modern religion” in Bellah’s sense.[47] Strain and conflict are not much in evidence in what they discerned. Following this interpretation, circumstances appear fortuitously to have been conducive to both institutional prosperity and continual individual self-transformation.[48] One of the major premises for this conclusion is the impression that in present-day Mormonism each man has apparently become, in effect, his own theologian, his own exegete, and even his own sect. Hence the problem of “Mormon literalism in theology” and the related problem of authoritarianism in the Church—which were central problems in O’Dea’s analyses—no longer exist, or, if they do, they have changed radically. O’Dea, incorrectly or too quickly or easily, took “Mormon ism at its word in matters of dogma,” according to Leone.48 What has evolved in Mormonism today is a style which enables the individual Mormon to live successfully and relatively untroubled spiritually in the modern world. The Church, far from being “crystallized in concrete,”[49] is producing “modern men.”[50]

This thesis is an interesting one; clearly it is worth more detailed development than is possible here. I have referred to it chiefly to point out that it appears to differ sharply from O’Dea’s conclusions. Perhaps the discrepancies can be accounted for on the ground that only intellectuals experience the “strain and conflict” which O’Dea discerned, and there are few intellectuals in the Mormon communities of Eastern Arizona which were studied by Leone and Dolgin. There may be more to it than that. Possibly there is a basic difference in understanding of the nature of religion and even of human existence generally. O’Dea might well have questioned the appropriateness of the construct “modern religion” to describe what is happening in and to religion today. (It is also doubtful that he personally would have been at ease in Bellah’s “modern religion.”) In any case, he would probably have been skeptical of a construct which closed the gap between the real and the ideal with relative ease, even if such a construct claimed to be supported by grass-roots data.

In his last piece on Mormonism, O’Dea focused on race as “a diagnostic issue” in reconsidering “sources of strain in Mormon history.” Here was another conflict between what is and what can or ought to be. Would Mormon doctrine be interpreted in such a way as to reinforce a defensive posture on this issue? Or would there be a renewal of “the original democratic and ethical spirit of Mormonism” in facing it?[51] The issue of race evidences, of course, a greater dilemma than that involved in the more immediate question of whether blacks should be accepted into the priesthood. It is related to the larger issue—the primary problem of our time, in O’Dea’s view—namely, the definition of what it means to be human in the world today.

The racial issue brings us back to the relationship between the real and the ideal and the question of whether there is any continuing tension between them. In the context of Mormondom, has the movement become so much a “modern religion” that purposeful communal action in accordance with the “Mormon values” O’Dea discovered has ceased to be either a viable or a desirable possibility? In the larger context of American and even world society, does one view America as “the best of all possible worlds”—as, in effect, the kingdom of God on earth? Or does one conclude that there is a more inclusive and better kingdom or society yet to be built?[52] Such questions presently may have a low priority. Yet, O’Dea taught that they must be asked, and that we must continuously seek for answers.

Thomas F. O’Dea’s Writings on the Mormons

“A Study of Mormon Values,” Comparative Study of Values: Working Papers, No. 2, October, 1949 (Laboratory of Social Relations, Harvard University).

Miscellaneous field notes from interviews in Salt Lake City and Ramah, New Mexico, 1950.

Mormon Values: The Significance of a Religious Outlook for Social Action, Ph.D. Thesis, Harvard University, 1953.

“A Comparative Study of the Role of Values in Social Action in Two Southwestern Communities,” with Evon Z. Vogt, American Sociological Review, Vol. 18 (1953), pp. 645-654.*

“Mormonism and the Avoidance of Sectarian Stagnation: A Study of Church, Sect, and Incipient Nationality,” American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 40 (1954), pp. 285-293.*

“The Effects of Geographical Position on Belief and Behavior in a Rural Mormon Village,” Rural Sociology, Vol. 19 (1954), pp. 358-364.*

“Mormonism and the American Experience of Time,” Western Humanities Review, Vol. 8 (1954), pp. 181-190.*

The Sociology of Mormonism: Four Studies, Publications in the Humanities, number 14 (Department of Humanities, Massachusetts Institute of Technology), 1955. Reprint of four articles above indicated by asterisks.

“Mormon Values: The Mutual Dependence of Belief, Action and Social Structure,” undated manuscript.

The Mormons (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957; paperback edition, 1964).

“The Mormons—Strong Voice in the West,” Information; The Catholic Church in American Life, March 1961, pp. 15-20.

“Mormonism Today,” Desert; Magazine of the Southwest, Vol. 26 (June 1962), pp. 23-27.

Foreword to the Phoenix edition of Desert Saints by Nels Anderson (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966).

The Sociology of Religion (Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall, 1966), especially pp. 44 and 70.

“Latter-day Saints,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1967, Vol. 8, pp. 525-529.

“Sects and Cults,” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 1968, Vol. 14, pp. 130-136, especially p. 133.

“The Sociology of Mormonism: Four Studies,” in Sociology and the Study of Religion: Theory, Research, Interpretation (New York: Basic Books, 1970). Reprint of four articles above indicated by asterisks.

“The Mormons: Church and People,” in Plural Society in the Southwest, Edward H. Spicer and Raymond H. Thomson, eds. (New York: Interbook, Inc., 1972; A Publication of the Weatherhead Foundation), pp. 115-166.

“Sources of Strain in Mormon History Reconsidered,” in Mormonism and American Culture, Marvin S. Hill and James B. Allen, eds. (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), pp. 147-167.

[1] The book was published by the University of Chicago Press in 1957. Of the approximately twenty reviews in scholarly journals only one was clearly negative. The rest ranged from somewhat cautious and critical to enthusiastic, with more in the latter than in the former category.

[2] American Sociological Review, Vol. 23 (1953), p. 104.

[3] Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 26 (1958), pp. 183-185.

[4] Western Humanities Review, Vol. II (1957), pp. 398-400. Nelson also reviewed the book for the American Journal of Sociology. He referred to it in that review as “the best general sociological analysis of Mormonism yet made by either a Mormon or a non-Mormon scholar. … ” Vol. 64 (1958), p. 673.

Reactions of church leaders were, one gathers, guarded. The Improvement Era refused to advertize the book on the ground that it was “in very poor taste” in “detailing the rites and ordinances which take place in the Mormon temples.” This statement was quoted by the managing editor of the University of Chicago Press in a letter to Thomas F. O’Dea, dated December 28, 1957.

[5] The other four were the Zuni, the Spanish-Catholic, the Navajo, and the Anglo-Saxon Protestant. The study was done under the direction of Harvard anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn.

[6] Among his papers are typed notes which record details of many of these interviews.

[7] “Scholarly Studies of Mormonism in the Twentieth Century,” Dialogue, Vol. I (1966), p. 22.

[8] For O’Dea on method and understanding (Verstehen) see his introduction to Sociology and the Study of Religion: Theory, Research, Interpretation (New York: Basic Books, 1970), pp. 3-19.

[9] (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1972), p. 508.

[10] Ibid., pp. 387, 501-509.

[11] Ibid., p. 508.

[12] J. Milton Yinger, The Scientific Study of Religion (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1970), p. 267.

[13] Linda K. Pritchard, “Religious Change in Nineteenth-Century America,” in The New Religious Consciousness, Charles Y. Glock and Robert N. Bellah, eds. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976), p. 308.

[14] Bryan Wilson, Religious Sects: A Sociological Study (London: World University Library, 1970), pp. 197, 200.

[15] H. Richard Niebuhr, The Social Sources of Denominationalism (New Haven: The Shoe String Press, 1954; reissue of 1929 edition), p. 160, and “Sects,” in The Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 1934, Vol. 13, p. 629; and Joachim Wach, Types of Religious Experience (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1951), p. 198.

[16] Joachim Wach, Sociology of Religion (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962; reissue of 1944 ed.), pp. 194-195.

[17] Calvin Redekop, “A New Look at Sect Development,” in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, Vol. 13 (1974), pp. 345~352-

[18] Robert Park and Ernest W. Burgess, Introduction to the Science of Sociology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1921), pp. 872-873. Bryan Wilson also refers to Mormonism as “a type of surrogate nationalism,” op. cit., p. 199.

[19] Mormon Values: The Significance of Religious Outlook for Social Action, Ph. D. dissertation, Harvard University, 1953, pp. 503-509.

[20] “Mormonism and the Avoidance of Sectarian Stagnation: A Study of Church, Sect, and Incipient Nationality,” in the American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 40 (1954), pp. 285-293. The same summary statement appears in The Mormons, p. 115. Ahlstrom quotes it from that source, op. cit, p. 508.

[21] “Sects and Cults,” in the International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 1968, Vol. 14, p. 133. In another context O’Dea wrote that the Mormons “became something resembling an ethnic group—but an ethnic group formed and brought to awareness here in America.” The Sociology of Religion (Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1966), p. 70.

[22] “Mormonism and the Avoidance of Sectarian Stagnation: A Study of Church, Sect, and Incipient Nationality,” op. cit. This study was reprinted together with three others on “The Sociology of Mormonism” in Sociology and the Study of Religion, op. cit. The citation is p. 121 of that volume. The nine other reasons listed by O’Dea are: 2) “the doctrine of natural goodness;” 3) “universal missionary understanding of the notion of ‘gather the elect;’ ” 4) “the temporal appropriateness of the doctrine in the late 1830’s;” 5) “the success of missionary work;” 6) “the withdrawal of the Law of Consecration;” 7) “the failures and consequent necessity of starting again;” 8) “the expulsion from the Middle West;” 9) “the choice and the existence of a large, unattractive expanse of land in the West;” and 10) “the authoritarian structure of the church and the central government which made it possible.” O’Dea had suggested numbers 3, 5, 8, 9 and 10 in his doctoral dissertation.

[23] “Mormonism . . . represents a retheologizing of much that had already been . . . secularized . . .,” in “Mormonism and the American Experience of Time,” the Western Humanities Review, Vol. 8 (1954), pp. 181-190; reprinted in Sociology and the Study of Religion, op. cit., p. 149.

[24] Ibid., p. 150. O’Dea was fascinated by the relationship between typicality and peculiarity in Mormonism vis a vis American culture. It is a theme to which he returned in various contexts, including his last essay on Mormonism: “Sources of Strain in Mormon History Reconsidered,” in Mormonism and American Culture, Marvin S. Hill and James B. Allen, eds. (New York: Harper and Row, 1972), pp. 147-167.

[25] Op. cit., p. 506.

[26] No Man Knows My History: The Life of Joseph Smith, The Mormon Prophet (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971), second edition, especially p. 419, also the whole treatment in the Supplement in the second edition, pp. 413-421.

[27] See, e.g., Brodie’s list of offices held, duties performed, etc., by Joseph Smith in the spring of 1844, Ibid., p. 366. Smith’s “platform” for the presidency seems grandiose. Among other things, he proposed to reduce membership in Congress by one-half and to pardon all convicts, and he also described himself as “the universal friend of man.” By comparison, however, his claims for the nation do not seem too far removed in expansionist tendencies from those of the winner of the election, James K. Polk, who openly advocated the annexation of Texas and openly laid claim to the whole territory of Oregon as far north as 540 40′ with the campaign slogan “Fifty- four Forty or Fight.” See Joseph Smith’s Views on the Government and Policy of the United States. First published at Nauvoo, Feb. 7, 1844 (Provo City, Utah: Enquirer Co., 1891).

[28] See Marvin S. Hill, “Secular or Sectarian History? A Critique of No Man Knows My History,” in Church History, Vol. 43 (1974), pp. 78-96.

[29] There is a fair amount of scholarly literature on early Mormon millenialism and an increasing amount on the notion of the political kingdom of God and the role of the Council of Fifty. Among the authors whose works I have drawn upon are Leonard J. Arrington, James R. Clark, Robert Bruce Flanders, Klaus J. Hansen, and Gustive O. Larson. Ernest Lee Tuveson gives special attention to Mormon millenialism in Redeemer Nation: The Idea of America’s Millenial Role (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968), pp. 175-186. He links Smith with William Miller, the most influential adventist of the period, under the heading “millenarian.” But he concludes that the Mormon view “is a uniquely American form of millenarianism.” (p. 176).

[30] Op. cit., p. 362. Smith’s concern to defend his followers from further attack was, says Brodie, “his justification for what otherwise might have seemed to be preposterous megalomania.”

[31] See Robert Bruce Flanders, Nauvoo: Kingdom on the Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1965).

[32] See especially Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter day Saints, 1830-1900 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958), Klaus J. Hansen, Quest for Empire: The Political Kingdom of God and the Council of Fifty in Mormon History (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1967), and Gustive O. Larson, The “Americanization” of Utah for Statehood (San Marino: The Huntington Library, 1971).

[33] As quoted by William Mulder in “Mormonism in American History,” Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 27 (1959), p. 66.

[34] Gustive O. Larson, op. cit., especially pp. 273, 300.

[35] “The Mormon people,” wrote Brodie in 1945, “are still bent on building the Kingdom of God, and everyone from the twelve-year-old deacon to the eighty-year-old priest is made to feel that upon him depends the realization of that ideal.” (Op. cit., p. 402).

[36] The Mormons, p. 150.

[37] It also precluded the development of metaphysics and even of philosophy itself, according to O’Dea. See especially the Conclusion to his doctoral dissertation.

[38] The Mormons, p. 233.

[39] Ibid., p. 222.

[40] He quoted one of his interviewees as saying that within the Mormon community “only the questioning intellectual is unhappy,” Ibid., p. 224. As a “questioning intellectual” himself, O’Dea must have resonated with the force and nuance of that statement.

[41] On sacramentalism see the Conclusion to O’Dea’s doctoral dissertation. On activism and contemplation see The Mormons, especially the Epilogue: “The basic need of Mormonism may well become a search for a more contemplative understanding of the problem of God and man,” p. 262. O’Dea quoted himself on this point in “Sources of Strain in Mormon History Reconsidered,” his last essay on Mormonism, op. cit.

[42] Note, e.g., several juxtapositions in his treatment of the “sources of strain and conflict” in The Mormons. Note also, e.g., the titles of three other books by him: American Catholic Dilemma, The Catholic Crisis, and Alienation, Atheism and The Religious Crisis.

[43] The Varieties of Religious Experience (New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1928), p. 79; see also Lectures IV-VII.

[44] Ibid., p. 91.

[45] [Editor’s Note: There is no footnote 45 in the body of the PDF. I have placed it here.] “Religious Evolution,” in Beyond Belief: Essays on Religion in a Post-Traditional World (New York: Harper & Row, 1970), especially pp. 39-44.

[46] Janet L. Dolgin, “Latter-Day Sense and Substance,” and Mark P. Leone, “The Economic Basis for the Evolution of Mormon Religion,” in Religious Movements in Contemporary America, Irving I. Zaretsky and Mark P. Leone, eds. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1974), pp. 519-546 and 722-766. See also Leone’s “The Evolution of Mormon Culture in Eastern Arizona,” in the Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 40 (1972), pp. 122-141.

[47] Leone and Dolgin differ from Bellah on one point: the role of institutions in “modern religion.” Bellah stressed the relatively unstructured nature of this kind of religion and the fact that it clearly departs from traditional church or institutional forms. Leone and Dolgin found the institutions of Mormonism to be conducive rather than inimical to personal development and to adjustment to the modern world.

[48] “The Economic Basis for the Evolution of Mormon Religion,” op. cit., p. 752.

[49] O’Dea, “Sources of Strain in Mormon History Reconsidered,” op. cit., p. 160.

[50] Leone, “The Evolution of Mormon Culture in Eastern Arizona,” op. cit., p. 141. Leone carefully qualifies this conclusion with the antecedent “In east-central Arizona. … “

[51] “Sources of Strain in Mormon History Reconsidered,” op. cit., p. 162, and, more generally, pp. 155 ff.

[52] O’Dea is reported to have said that if he were to return to an intensive study of Mormonism he would focus on the question of what has happened to the kingdom building drive in recent times, particularly in light of the expansion in church membership beyond the borders of the United States.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue