Articles/Essays – Volume 07, No. 1

Three Myths About Mormons in Latin America

Perhaps the most dramatic growth of the Church in recent years has been in Latin America where the Church has involved itself in large scale educational and other programs. In this article, Professor LaMond Tullis explores certain misunderstandings which some American Mormons have with regard to their brethren south of the border.

For the most part, Mormons have been a socially homogeneous people. True, the initial Anglo-American stock was reinforced from time to time by immigrants from Western Europe, but these converts were quickly absorbed into the Church’s social and cultural mainstream. Although successful missions were established among the Indians and especially among the Polynesians, it was nevertheless the English-speaking white Americans who gave the Church its leadership and set the tone of its culture. In recent years, however, baptisms have rapidly increased in Asia and Latin America, resulting in a changing profile of Church membership.

Latin Americans, for example, are now becoming Mormons at a breath-taking rate. They accept the Prophet Joseph, the gospel principles and ordinances enunciated by him and other prophets since his time, and also the spiritual guidance of present Church leaders. But there, outside the spiritual and moral realm, likenesses between Latin and Anglo Mormons frequently end. Our Latin American brothers, with notable exceptions, do not come from an economically well-off and relatively satisfied middle class, or even from a rural yeomanry. While members of the privileged classes do join the Church in Latin America, they are few in number compared to those coming from the lower social and economic strata. As a result, Latin American Mormons generally do not live in the manicured suburbs of the region’s giant and impressive metropolises, drive on its superhighways, or enjoy its social clubs.

Particularly is this true for economically lower-class Mormons in the “Indian lands” of Mexico, Guatemala, and Andean South America. As did similarly deprived and frequently illiterate Anglos from Great Britain a hundred and thirty years ago, they are flocking to the Church in unprecedented numbers. Indeed, so great is the current rate of influx that one frequently hears of interesting if not astonishing crystal gazing. Within several decades, at the present rate of relative growth, Spanish will become the predominant tongue among new converts in the Church. A jest? No Mormon Latin Americanist I know would advise taking bets against what indeed may become a remarkable change in the complexion of Church membership.

Even under the best of conditions most groups which expand as rapidly as the Church has can expect to experience some growth pains, not only in terms of organizational efficiency, but in terms of human understanding as well. Three time-honored, Anglo-Mormon political and social myths tend to block understanding and hinder the growth of brotherhood between ourselves and our Latin American converts. These myths thus prevent the creation of spiritual oneness out of cultural, linguistic, ethnic, and social diversity. An examination of the three shows how mythmakers can and frequently do exacerbate the very problems they sincerely wish to avoid. At a time when Church leaders are making impressive efforts to convey the Restored Gospel to many peoples, it is unfortunate indeed that cultural blindspots and ideological jingoism should hinder the process. In many instances the near-sightedness derives from a vast misunderstanding among the Church’s North American middle-class member ship—in part because we have misread the analogies out of our own past—as to what it means in a social and political sense to be a Mormon in an under developed, revolutionary land.

“Just preach them the Gospel and everything will be all right,” some say. What does that mean? If whatever is meant does not square with the realities of life in Latin America, then, all good intentions and best efforts aside, we may impede rather than facilitate the spread of the gospel there. If our perception of Latin America is wrong, the three myths, which cloud the vision of many Church members as they look southward, are partly responsible.

Myth Number One

Becoming a Mormon in the total sense equips one with all he needs in order to develop, progress, and flourish, not only spiritually but also temporally. Having acquired the appropriate attributes, underprivileged Latin American Mormons therefore can, as did the Anglo pioneers who blazed trails before them, become masters of their own environment.

Partial Truths

This assertion has just enough truth in it to be dangerous. Certainly, if one assumes that people who search out the Church also strive to escape illiteracy, disease, and hunger, or to progress from whatever they are to what they newly aspire to be, then becoming a Mormon sometimes helps. “Mormonizing” oneself is both a spiritual and an intellectual experience. Those touched by the gospel are motivated to progress, to improve themselves, and to help others to do the same. But many converts so motivated are frustrated by an environment which so shackles them that “pulling themselves up by their own bootstraps” is more a reflection of dreamers than it is a reality of people who live in the real world. Mythmakers are either ignorant of or choose to ignore one Latin American reality—the pervasive existence of a rigid social structure which makes attempts by non-privileged classes to alter social and economic relation ships not only difficult, but frequently dangerous and sometimes fatal.

For most people, environmental bondage hampers motivation and enthusi asm for temporal progress. Only ascetics flourish under such conditions. Everyone else dreams of escape. Whatever else Mormons are, they are not ascetics. When their shackles remain tight for a long time, their dreams, like their spirits, tend to fade, and the resulting casualty rates are high. That is the problem.

In modern times, motivation and desire in the absence of a reasonably open, flexible, and development-oriented society—or at least an available frontier which no one else wants—produces frustration and rancor, leading eventually either to a defeatist resignation or radical and aggressive behavior. In either case, commitment to the Church tends to suffer. In many Latin American countries, and certainly in those of Guatemala and the Andean South where a rapidly growing number of Church members now reside, the frustration index is accelerating rapidly. Thus, while the baptismal rate is high, so also is the drop-out rate. Mythmakers do not see this problem. In the meantime, in some countries, a whole generation of Latin American Mormons has been lost to the Church.

In Latin America it is the social and political elite, not the Mormon Church, which currently controls opportunities for temporal progress, and the Saints do not ordinarily belong to a social stratum which would guarantee easy accessibility. Indeed, for some members of the Church the doors to temporal development remain totally locked. The spirit is touched; aspirations skyrocket; but life’s circumstances frequently remain the same, or perhaps even deteriorate—children die of malnutrition and intestinal parasites, the schools remain either unavailable or abysmally deficient, and occupational opportunities continue to be acquired less through personal ability than through political and social “contacts” (and when one becomes a Mormon he frequently has to break all those contacts).

Many early British converts fled such circumstances in large numbers a hundred and thirty years or so ago, proceeding forthwith to the Promised Land. They could escape their shackles by emigrating from Europe and seeking opportunities in Zion. Where, one is tempted to ask, should the current wave of frustrated Latin American Mormons go? Where is their “promised land?” Certainly it is not Utah. The Church now officially discourages any such migration.

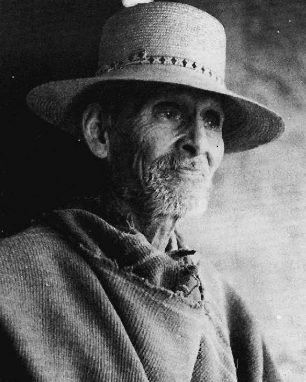

What, for instance, is Fermin to do? I can see him standing in the patio of a simple house once used as a chapel, gratefully wearing a hand-me-down suit left behind by some departing missionary. He is clutching his Book of Mormon to his chest. His wife, dressed in the colorful Indian fashions typical of the area, is by his side. So are his two small daughters. With some danger to his personal safety Fermin had broken away from his old life and subsequently became a Mormon. Now he holds the Melchizedek priesthood. Like any convert to the Church he has changed many of his former ideas. He also has abandoned his “home.” Not for the usual reasons, however, for Fermin is a peasant running from the law.

Before meeting the Elders, Fermin had decided to escape. No longer would he work for his landlord four days each week without pay. Nor would he honor the debts the master claimed his great-grandfather had incurred decades before. As customary in his area, the lords use such devices to insure themselves a cheap captive labor force for their plantations. An Indian can not move until his family obligations are paid. That is the law. But how can the debts ever be paid? One who lives near the subsistence level can hardly set aside funds to pay off some ancient relative’s alleged debts. So when Fermin could no longer tolerate the oppression, he fled, for to be rebellious and remain on the plantation was to endanger his life. In his new home he found the Elders and became a member of the Church.

Now the police are looking for Fermin. And when they find him he will have to return to the plantation. The problem for aspiring young men of his kind is that their entire country has been a “plantation,” alternately run by traditional oligarchs, a selfish middle class, communist ideologists, and a reactionary military. “We believe in . . . obeying, honoring, and sustaining the law.” And so does Fermin. But what does he do if the laws are patently unjust, intending not to serve but rather to exploit a certain class of people?

While the “labor prisoners” in Fermin’s land resemble in many ways the earlier indentured servants of Great Britain, and while many such individuals both in Great Britain and Latin America have become Mormons, at least one great difference exists between the two groups. Those like Fermin must stay and perhaps face their ordeal; the early British Saints could emigrate. Where can Fermin go? He might try to pay off his great-grandfather’s alleged debts and thereby purchase his “freedom.” But the lords might think that an undesirable precedent. In any event, he probably could not raise the money. He is not qualified for a well-paying job. Sixty percent of all adults in his country are illiterate. Except for the few skills which the missionaries taught him, Fermin is simply another figure in those statistics. The state has done little to educate him or thousands like him. Those services are destined first to the lords, and second to the “Europeanized” people who live in cities and towns.

Many Anglo-American Mormons (and a few privileged Latin-American Mormons) have little comprehension of these and related blocks to social and occupational mobility. Even in the days of Nauvoo there was nothing comparable. Perhaps the condition of racial minorities in the United States prior to the Civil Rights movement best typifies the difficulty of the environment facing many of our new members in Latin America. Few Anglo-Americans can fully sense the task of moving from economic servitude to the freedom and dignity worthy of a child of God. Fermin understands.

Myth Number Two

What is good for American business in Latin America is good for Mormons there too. Corollary A: There is a close identity of interest between United States foreign policy and the Mormon Church in Latin America. Corollary B: Contrary to many of their countrymen, most Latin American Mormons love the United States government and most of what it stands for. Corollary C: Mormons in Latin America appreciate the virtues of capitalism.

The Other Side of the Coin

Mormons in the United States have prospered economically within a more or less well-regulated system of free-enterprise capitalism. Practitioners of American capitalism have in most instances reflected the logic of President J. Reuben Clark’s 1946 admonition to his business and banking friends.[1] He warned those capitalists that an unbridled pursuit of profits was fraught with social and political danger unless the welfare of the working man was well considered. “I have not approved and do not approve/’ he told them, “of capital’s weapons—the blacklist, lockouts, the grinding out of the maximum returns for the minimum of wage outlay, even the imposition of starvation wages that too often have been capital’s means of dealing with labor in the past. These have worked great injustices that must not be repeated.” They must not, he emphasized, because only the communists and socialists would benefit. Free-enterprise capitalism (which, when moderated, he considered superior to other man-made economic systems) would otherwise soon come to an end.

Capitalists and entrepreneurs in the United States, whether voluntarily or in response to government coercion or social pressure, have generally bridled their exploitation of labor. Not so in much of Latin America. Accordingly, the consequences there have approached a magnitude which President Clark feared might arise in any country if powerful groups consistently failed to temper their exploitative habits. “Some plan of better equalizing the distribution of the proceeds of production must be found,” he said. His own plan, he went on to relate, was “a principle of economic partnership . . . which labor and capital should try to work out on some basis, for the welfare, indeed salvation, of each of them, and for the preservation of our civilization.”

Latin American capitalists (and some foreign capitalists operating in Latin America as well) for a long time had neither social pressure nor government coercion to bridle them. They created a bad image for the whole economic system. Now, in spite of a few reforms during the past decade, many Latin Americans feel that further “quiet and gradual reforms” are no longer sufficient. The time is past, they say, for the rhetoric of deceit and duplicity. Substantial changes must be made to improve the life of the common man. Thus, much current thinking about social, political, and economic change in Latin America has been influenced by non-capitalistic—frequently even anti-capitalistic—ideas. Most of them carry a socialist or Marxist flavor. But as any Latin American will tell you, it does not necessarily follow that to be a socialist, or even a Marxist, is to be a communist. Indeed, some Catholic priests in the area, men who consider communism to be anathema, have become Marxist revolutionaries to affirm their Christianity. In most countries the practical consequences are a “mixed” economy (heavy entrepreneurial participation by government in areas where private capital has not been forthcoming) and considerable suspicion of United States capital investors. Such trends enjoy the sympathies of some Mormons.

For example, take Martin, a brilliant South American student I came to know well in one of my classes at B.Y.U. last year. He used to be a Marxist. Indeed, at one time he even belonged to the Communist Party. Since becoming a member of the Church, however, he no longer belongs to the Party. But he still sympathizes with many of its economic goals. Today, you might call him a socialist. “What you Anglo-American Mormons should do,” he told me on one occasion, “is get on the receiving end of Latin America’s capitalism and free enterprise system for a while. You’d soon respect a different point of view from the one you now have; and you would probably stop talking about capitalism as if it were part of the gospel. In our countries the employers and landlords have been selfish and brutal. And they have used their money and power to oppress and exploit us. Capitalism and free enterprise where I live are not of God; if not creations of the Devil, they are at best inventions of man.

Martin does admit that not all Latin American free-enterprise capitalists are so bad. A few employers, state and private alike, are much more mindful of their employees than they used to be. And many of them are United States business men. But there is no question that historically, capitalism has been oppressive for the common man in Latin America. The image and, indeed, much of the fact lives on. There is talk of change, even revolution.

“It cannot be denied,” said President Clark, even of his own country, “that capital has enslaved labor in the past.” In Latin America, capital frequently still does. Where social structure is rigid and mobility low, the fruits of free enterprise are neither free nor very productive. They serve to legitimize “servitude” rather than encourage initiative and productivity. Common people there are becoming increasingly angry and discontent. They want a change. Thus most revolutionary ideas in Latin America, regardless of their ideological stripe, are loudly anticapitalist. The social casualties of any substantial change will include the oligarchs, large landowners, many United States business interests, selfish and cruel politicians, and some innocent bystanders. Adam Smith’s capitalism, as interpreted by its traditional Latin American practitioners, is on its way out. With it will also go its chief beneficiaries.

What is good for American business in Latin America, therefore, is not necessarily good for Latin American Mormons. In fact, the traditional interests of United States investors in Latin America—and, therefore, much of the perceived interest of the United States itself—may directly conflict with the current spiritual and developmental interests of the Church. In any event, to the extent that the Mormon church takes on the aura of an “evangelical capitalist institution,” as some Anglo-American Mormons would like it to be, it will needlessly be subjected to increasing amounts of anti-capitalist criticism.

For the aspiring Latin-American peasant, awakened Indian, second-generation urban slum dweller, or university student in the Church, the Anglo American Mormons’ frequent “religious” commitment to capitalism therefore makes no sense at all. One of the reasons, of course, is that the two kinds of Mormons are not talking about the same kind of economic institution. The excesses of capitalism in North America have been bridled. In Latin America, until recently in some countries, they have not. Furthermore, unlike the United Order which we have chosen not to practice, capitalism, protestations to the contrary, is not part of the gospel.

Thousands of Latin-American Mormons live in a tense and frustrating environment, a world unlike that of most of their Anglo-American counterparts. In many respects it is a world strained nearly to the breaking point. In spite of it all, however, their countries are alive with a spectacular newness. People are working, searching, and striving. Thoughts and hopes which have incubated for generations are suddenly hatching to become part of the abundant religious and political excitement visible in nearly every country. And in addition to the revolutionary political and economic ideas of Marxism and socialism, there are those revolutionary spiritual ideas of the Restored Gospel now rapidly spreading throughout the land.

In general, it is not the “natural” pro-capitalists—the traditional lords and the new rich—who are being attracted to Mormonism in Latin America. The rich there do not seek baptism; perhaps they already have their kingdom. The missionaries do not usually convert the politically powerful (although a few second-generation Mormons, rising from humble conditions, are now acquiring responsible positions in at least one country); their secular gospel has already consumed them. Nor does the Church attract very many traditional lords; their interest is strictly of this world. The people being baptized are the “humble fishermen” of the modern day. They are the ones who have sought God and found Him. More importantly, they are not the traditional poor with no vision, but rather their sons and daughters who, while still poor, nevertheless aspire to a new existence. They are not the “old middle class,” but rather their uprooted children who are searching for a new value system to give meaning as much to this life as to the next one.

Thus, missionaries have success with those who aspire to a better life and still have hope, among those who are not merely discontented with their present conditions but also concerned about their relationship to God. They also baptize those who come to believe that Mormonism offers not only a plan of spiritual salvation but a worthwhile philosophy about temporal salvation as well.

From the perspective of many Latin-American Mormons, the flag-waving, let’s-all-get-back-to-the-principles-upon-which-this-nation-was-founded Anglo-American Mormon does indeed present a curious, if not incomprehensible, picture. Especially is this so when the United States Government, following a “whatever is good for American business is good for America” maxim, lends its support to petty Latin American tyrants, dictators, and military overlords whose only redeeming quality is frequently their professed “anti communist” stand (even though they repress their own people) or their alleged friendship for the United States and its business community. Such “leaders” have little friendship left over for the common people of their own countries, including Mormons.

Myth Number Three

Leaders of the Mormon church are insensitive to the temporal needs of their more relatively deprived followers and, indeed, are known to subscribe to Myth Number One.

The Little Known

No doubt Church leaders differ about the role the Church, as an institution, should play in the temporal development of its membership. However, recent trends indicate an increasing concern by the Church for the temporal needs of its more deprived members in Latin America. In many areas where the Saints are blocked from development and progress—no matter how hard they tug at their bootstraps—the Church is on the move temporally as well as spiritually. Programs for the development of literacy, health and nutrition, practical education, and economic development are in various stages of planning or implementation. Echoing Joseph F. Smith’s belief that a religion which cannot save a man temporally cannot hope to save him spiritually,[2] the first presidency announced in 1968, “The historic position of the Church has been one which is concerned with the quality of man’s contemporary environment as well as preparing him for eternity. In fact, as social and political conditions affect man’s behavior now, they obviously affect eternity.”[3]

Programs designed to solve temporal problems cost money. To pay for them, greater sacrifices may be required of affluent Mormons, including middle class, Anglo-American Mormons. Indeed, in the not too distant future, conversations regarding Anglo ward budgets may shift from whether to pad the chapel benches to “How many schools did your ward build last year?” ($500 will build one in Bolivia.) If such a radical change is too much for some of the adults, fortunately it does not appear to be so for some of their idealistic children. A striking number are anxious to walk the extra mile. Already they are involved in Partners of the Alliance, Ayuda, the Cordell Anderson Foundation, and many other programs working for the temporal welfare of that stratum of Latin Americans who are joining the Church in large numbers.[4] The fifty-fifth ward Relief Society of the B.Y.U. Fourth Stake is a particularly striking example. This past year the sisters donated over a thousand hours sewing school uniforms for a little bootstrap school in Guatemala where some of our brothers and sisters only now are learning to read and write. Quite aside from the temporal assistance provided, such experiences also foster lasting spiritual bonds.

A new generation of Mormons is now emerging—still of high school and college age—one perhaps better equipped than ever before with the tools and perspective required to match the thrust of a church that, by divine direction, is rapidly becoming international. They will not forget the religious foundation which the past generation established, enduring, as indeed it has, its own temporal deficiencies, spiritual trials, and threats to survival. The threats now, however, are of a different kind. Some of the perspectives need to be also.

Hopefully those who subscribe to the above-mentioned myths will abandon their mistaken notions and, by so doing, win the confidence and respect of their children. And what about those whose cultural, political and social ideals are more dear than the “brotherhood of man and the fatherhood of God?” Well, the gospel always has been a bit selective, as much among those whom it reaps as those it retains. There is no indication it will discontinue being so as its influence shifts eastward and southward.

The Kingdom, we are told, is won by those who can stay in the race. Although places for occasional rest and recuperation are required, the oases of mythland ought to be avoided at all costs.

[1] President Clark’s comments are found in “American Free Enterprise,” Address delivered Friday evening, December 6, before the Allied Trades Dinner of the Mountain States Travelers in the Newhouse Hotel, Salt Lake City (n.p., 1946).

[2] William E. Berrett and Alma P. Burton, eds., Readings in L.D.S. Church History (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1958), III, p. 364.

[3] The First Presidency, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, “Citizens Obligations,” Deseret News, September 7, 1968 (with correction of September 11).

[4] [Editor’s Note: In the PDF, this footnote states it’s “3” rather than “4.”] For some extended remarks on this subject, see Wesley W. Craig, Jr., “The Church in Latin America: Progress and Challenge,” Dialogue, 5, (Autumn, 1970), 66-74.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue