Articles/Essays – Volume 56, No. 4

Tiny Papers: Peruvian Mormon Substances of Relatedness

Listen to a conversation about this piece here.

JACOBA:[1] I have my genealogical abilities, and I wield them as I see fit.

JASON: And you saw fit to marry your son to Chalo’s daughter?

JACOBA: Correct. Very correct. And it’s best if those who marry are not primos, so if I could find a document to eliminate the blood, all the better.

Translated interview transcript. Camp Atoka, Utah. July 3, 2017.

Within Jacoba’s Latter-day Saint kin-building model, it was important that her Utah-dwelling children and grandchildren marry not only Mormons[2] but Peruvian Mormons. In one of her many matchmaking trips back to her homeland of Peru for that very purpose, she discovered that her son Ammon had an affinity for her nephew Chalo’s daughter Leslie. According to a Peruvian Mormon model of genealogy mixed with an Anglo[3] Mormon one, Ammon and Leslie were primos. Therefore, according to the Peruvian incest taboo, it was best that they not marry each other. At least, they thought it was best until Jacoba found a papelito (tiny paper) that changed Chalo’s ancestors and, as such, the marriageability of his descendants.

Below, I provide the digitally recorded conversations that occurred around the campfire both before and after that epigraphic excerpt. In table 1, I provide relevant data describing this study’s cast of characters, some of whom sat around that campfire. Most of all, throughout this article, I provide a context for understanding how kinship is a social construct. Kinship is materially built, not biologically inherent. To accentuate kinship’s materiality, I use jarringly tangible words, such as “substances.” During my study, Mormon substances interacted with Peruvian substances to coagulate into a Peruvian Mormon kinship that dissolved the membrane separating relations often taken for granted as biologically determined. Ultimately, Peruvian Mormon kinship blurred the boundary that distinguished cousins from siblings and even ancestors from descendants.

I use the terms “kinship” or “relatedness” to mean the sharing of both literal and metaphorical substances in ways that make the sharers into “relatives.” I call the various means through which kin substances are shared “kin systems.” In this article, I will demonstrate that the Anglo Mormon kin system—meaning the kin system of Euro-American, white members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—used unidirectional pathways for substance sharing that were visualized as vertical and hierarchical. Indeed, they were depicted as “family trees.” Therefore, I consider the Anglo Mormon kin system that I observed during my study to have been largely “arboreal.” In contrast, the Peruvian Mormon kin system was more “rhizomatic,” meaning that it contained fewer predetermined pathways and that the sharing of kin substances occurred in multiple directions, upending generational boundaries in ways that mixed ancestor-to-descendant hierarchies.

| Relationship to Utah | Relationship to Jacoba (in US kinship terminology) | Religious background | |

| Jason | Birthplace in 1979 | Spouse of Jacoba’s half-sister Nilda’s daughter Elvira | Mormon |

| Jacoba | Immigrated in 1982 | Self | Catholic-to-Mormon |

| Arcadio | Immigrated in 1982 | Jacoba’s spouse | Catholic-to-Mormon |

| Ammon | Birthplace in 1982 | Jacoba’s son | Mormon |

| Nilda | Immigrated in 1994 | Jacoba’s half-sister | Catholic-to-Mormon |

| Elvira | Immigrated in 2000 | Jacoba’s half-sister Nilda’s daughter | Catholic-to-Mormon |

| Mido | Immigrated in 2001 | Jacoba’s half-sister Nilda’s half-brother | Catholic |

| Carol | Immigrated in 2001 | Spouse of JAcoba’s half-sister Nilda’s half-brother | Catholic |

| Marina | Immigrated in 2014 | Had children with the man who had children with Jacoba’s mother | Catholic |

| Chalo | Immigrated in 2016 | Raised as a brother to Jacoba’s nieces and nephews | Catholic-to-Mormon |

| Leslie | Immigrated in 2017 | Jacoba’s non-blood nephew Chalo’s daughter and JAcoba’s son Ammon’s spouse | Catholic-to-Mormon |

| Riana | Immigrated in 2017 | Jacoba’s son Ammon’s daughter | Mormon |

Table 1. Table of relevant study participant relationships. Participants are listed in order of their arrival to Utah.

During my ethnographic research with Anglo and Peruvian Mormons in Peru and Utah from 2014 to 2021, nobody exemplified the complexity of those substantial interactions more than Jacoba. Through her kin-building, Jacoba combined her Peruvianness and her Mormonism in unique ways, revealing the substances that she used as kin-building materials to be, among others: blood, food, drink, and tiny papers.

Linguistic Resistance to Blood and Tiny Papers

Jacoba Arriátegui was one of the principal participants in my study on Peruvian Mormonism. She was also my tía. She was also the activities coordinator for our Spanish-speaking congregation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter, the Church) in Salsands,[4] Utah, a congregation that I joined as part of my full-time year of anthropological field work in 2017. Among many other positionalities, Jacoba was a Peruvian immigrant,[5] a Lamanite,[6] a Latina in Utah,[7] a leader in her barrio hispano,[8] a naturalized US citizen,[9] a mujerista theologian,[10] a returned missionary (having served an official, full-time LDS mission as an elderly woman together with her spouse), a matriarch,[11] a wedding decoration business owner, an LDS temple-recommend holder, and a Saint. However, I am reserving most of those facets of her personhood for future publications. Here, with the permission of my friends and family whose everyday realities formed the composite ethnographic character whom I have chosen to name “Jacoba,” I delve instead into another aspect of the crossroads between her Latter-day Sainthood and her Peruvianness. In this article, I focus exclusively on Jacoba’s identity as a kin-builder.

This article is about “kinship” and other terms that pertain to making humans into relatives. Words like “primos” and “tía” represent a few more of those kin terms. I leave them in Spanish for a reason. They are untranslatable. Though they roughly translate linguistically into “cousins” and “aunt” respectively, they translate relationally within Peruvian Mormonism into complex concepts that encapsulate more emotions and information than that which “cousins” and “aunt” evoked in the Anglo Mormon society that raised me inside a racially and religiously exclusive suburb of Utah in the 1980s and 1990s.[12] I grew up in a society wherein it was difficult “to convince an American that blood as a fluid has nothing in it which causes ties to be deep and strong.”[13] In other words, I grew up around people who never paused to consider that DNA—blood—might not be the only kin substance in the universe and that gonads, gametes, and adoption agencies might not be the only kin pathways. With the advent of genome sequencing and the use of DNA as forensic evidence, the already difficult work of convincing Anglos that there were substances other than DNA that made kinship “real” rather than “fictive” only became harder, especially among US Mormons, who, by that time, treated biogenetic and documentable kinship “as a vehicle of salvation.”[14] Therefore, even though I was a fluent Spanish speaker by the year 2000, having served a two-year mission in Bolivia, it did not occur to me that the meaning of “primos” and “tía” could have at its root anything other than a linearly sequential series of shared wombs and shared DNA. Alternatives to the kin models of my youth were not visible to me until Jacoba began to incorporate me into a Peruvian Mormon kin system that was not nearly as biogenetic and arboreal as the Anglo Mormon one that had structured my emotional attachments to those to whom I felt related. Once Jacoba became my tía in a sense just as real as the sense that my mother’s “sister by blood” was my “aunt,” I saw the word “tía” as untranslatable.

In 2001, in a sacred “sealing” ceremony within the holy walls of the Church’s Salt Lake City temple, my Peruvian Mormon fiancé Elvira[15] and I formed the nucleus of a Church-sponsored, heaven-approved, eternal, couple-centric kin entity called “a forever family”[16] that united my Anglo Mormon rearing with Elvira’s Peruvian Mormon rearing. Thus situated, I have inhabited a decades-long vantage from which to both shape and observe the convoluted melding of two disparate systems of relatedness: the Anglo Mormon and the Peruvian Mormon. In marrying Elvira, I married into a conglomeration of mostly Mormon, mostly Peruvian relatives that called itself, always in Spanish, La Familia. Jacoba was the matriarch of La Familia’s Costa clan, a staunchly Mormon faction of La Familia. Jacoba’s husband Arcadio Costa’s business near Salsands, Utah formed the principal node on La Familia’s network of family-based migration from Peru to Utah ever since the early 1980s.

Family-based migration is a phenomenon whereby a few members of a family move into a new country and expend the energy necessary to establish themselves socially, economically, spiritually, and linguistically. Upon breaking many of the barriers necessary for such establishments, they are then able to facilitate the arrival of more members of the same family to the exact same area. These incoming family members do not have to expend nearly as much energy as their predecessors to function in the new place. One way to stifle family-based migration, from a xenophobic nation-state’s perspective, is to limit the definition of “family members.” After the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, the United States was no longer able to deliberately exclude migrants simply for not hailing from historically white countries. However, Congress wrote into the act itself a way to ensure the same racist result as the scientifically racist National Origins Formula that the act ostensibly abolished.[17] Instead of excluding migrants for not having white ancestors, the act, which remains in effect to this day, excludes migrants for not having white kin systems. It does so by only allowing certain, sufficiently assimilated migrants—as individuals, not collectives—to “petition” only certain family members for US immigrant visas. The act designates the only family members eligible for such petitioning as “direct family members.” The “direct” aspect of that designation was originally thought to “naturally” denote only four kin categories: spouses, parents, siblings, and children. Even more “naturally,” the “family members” aspect of the designation means that the only substances that can truly relate a potential immigrant to the individual petitioner are DNA (blood) or legal documents (tiny papers). Conveniently for its white supremacist signatories, the 1965 immigration act’s designation of “family members” does not allow for food, drink, or the many other substances that, when shared in place and over time, create true relatedness within some of the world’s least white places, such as those found in Peru.

In sum, the act’s “conditional inclusion”[18] only allows entry to migrants who can squeeze their transnational, abundance-model kin systems into a stifling, scarcity-model kin system that stresses “nuclear ‘family stability’ grounded in strict gender roles.”[19] Only those migrants willing to appear to relinquish what family means for them in their home countries get to be counted as model minorities with “strong family values”[20] in the United States.

During my study, La Familia did not willingly capitulate to US kin systems, and they wielded Spanish kin terms as if to mark their resistance to the 1965 act’s racist kin limitations. I observed that even the monolingual English-speaking, Utah-born, LDS, Peruvian American teenage members of La Familia switched to Spanish for kin terms that they considered untranslatable, such as “primos,” “tía,” and “La Familia.” When I became a doctoral student of anthropology in 2014, that untranslatability intrigued me. I began to ask about it. One of my Peruvian American nieces (sobrinas) responded in English with an utterance similar to the following.

I say, “mis primas” because it’s not like they are my “cousins.” That just sounds gross. Like, eww, “COUSINS!” Seriously? That’s like a white thing to say. No offence, Tío Jason, but yeah. Cousin is not primo. Not at all. Are you kidding me? Primo is familia. It’s strong. It’s complicated. It’s deep. Not like some weakling “cousin.”

What also intrigued me was that La Familia was predominantly Mormon and that Mormonism had an outsized focus on family in comparison to other Christianities.[21] I began to wonder how it would feel to be unable to translate from one’s dominant society the very concept—family—foundational both to one’s personhood and to one’s religion.[22] I formulated a research question. How did Peruvian Mormons square familia with family without losing either their Mormonness or their Peruvianness?

In this article, I argue that as Jacoba built La Familia within a context of Anglo Mormonism’s forever family, she ran into barriers stemming from the clash of two different kin systems, the Mormon and the Peruvian. I further argue that as she dug paths to circumvent those barriers, she revealed that the material and spiritual substances of her relatedness held the power to sustain a kin system without barriers. In my understanding, that kin system formed the core of Peruvian Mormonism.

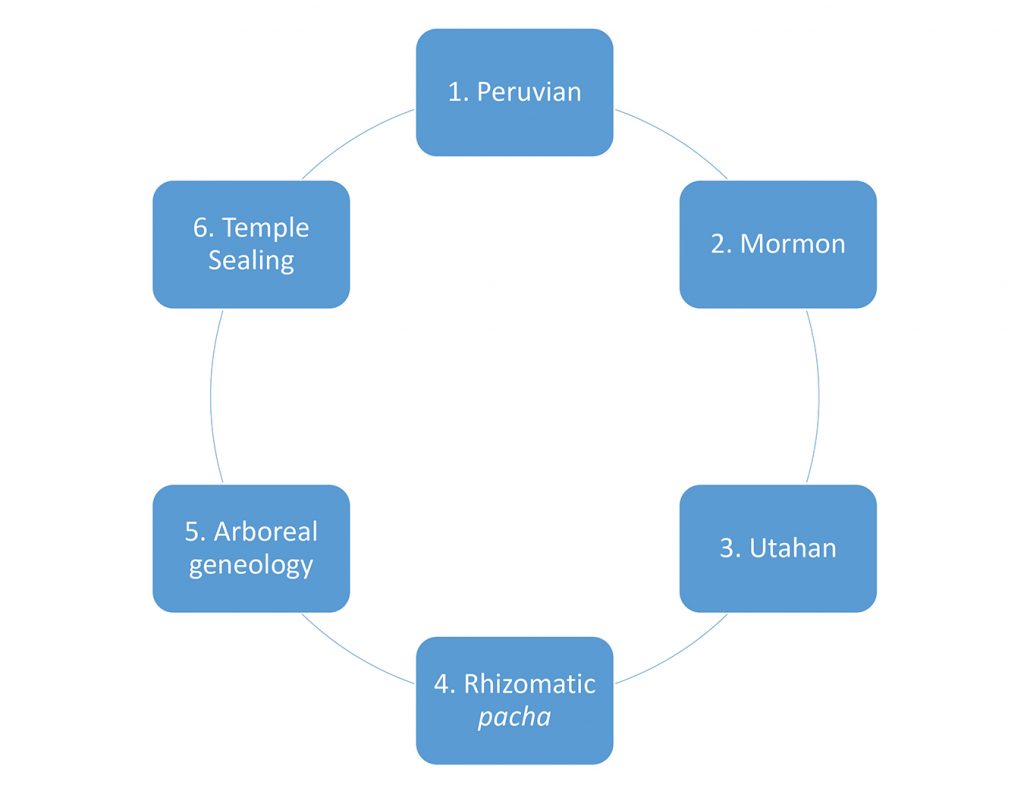

Often, in order for Jacoba to consider other humans to be kin, she first had to manipulate her Peruvian Mormon substances of relatedness—blood, food, drink, and tiny papers—to (1) build humans into Peruvians, (2) build humans into Mormons, (3) build humans into potential residents of Utah, (4) build humans into a collective, rhizomatic system of place-based mutual indebtedness called “pacha” (explained below), (5) build humans into individual slots on her FamilySearch.org family tree, and (6) ritually graft humans onto that tree inside Mormon temples in ways recognized both on earth and in heaven in an act called “sealing” (also explained below). Jacoba did not conceptualize those building plans as discrete “phases” as I have done above (see figure 1), and she certainly did not proceed through them in numerical order during her kin-building. However, she only fully admitted humans into La Familia when they met the essence of all six of those aspects of kin construction.

Figure 1. Jacoba’s phases of kin building.

Cancelling Blood with Food, Drink, and Tiny Papers

As kin-building required intense work, Jacoba preferred it when some of her six phases were already complete. Therefore, in seeking a new daughter-in-law, she was overjoyed when, during a Halloween party that she sponsored in Lima among the cadre of La Familia that still lived in Peru, her son Ammon appeared to be falling in love with someone who fulfilled all but Phase Three, Phase Five, and Phase Six. Leslie was already Peruvian (Phase One) and already Mormon (Phase Two). Furthermore, she already called Jacoba “tía,” meaning that she had danced enough Valicha (a folkloric dance from Cusco that Jacoba believed stemmed from her Book of Mormon ancestors, the Lamanites), drunk enough of Peru’s national soft drink, Inca Kola, and eaten at enough of Jacoba’s polladas (chicken-frying fundraisers) in close enough proximity to La Familia to become kin to La Familia in a place-based, convivial way (Phase Four). Only three challenges remained. Phase Three involved bringing Leslie to Utah with a tiny paper called a fiancé visa, which I will address later. Phase Six involved temple sealing, which I will also discuss later. Phase Five, which I will discuss now, involved adapting a rhizomatic kin model into an arboreal one in order to change the specificity of Leslie’s relationship to Jacoba. Leslie needed to transition from being Jacoba’s son’s prima to being Jacoba’s son’s wife. In so doing, Leslie would take her hierarchical place below Jacoba upon an arboreal diagram of “direct-line ancestry” that Jacoba refurbished in order to get the abundance model of La Familia closer to counting as “a forever family” within the scarcity model of Anglo Mormonism.

Before delving into the substances of relatedness that Jacoba manipulated—and eliminated—in order to perform such a feat, I must first attempt to translate the untranslatable so as to elucidate the focus group transcript below and its talk of “blood” and “documents.” In La Familia, there were two generational groups that had little to do with what Anglo Mormons might have called “blood descent” and more to do with relationally dancing upon, eating from, and spilling nonalcoholic drink onto the same local spot of earth from whence the rhythms, foods, and drinks sprang. Those generational groups were called “Los Primos” and “Los Tíos.” If you were a member of either of those groups—meaning that you shared a sufficiently complex mix of blood, food, drink, and tiny papers over a sufficient amount of time with La Familia—you would use “tío” or “tía” to refer to most members one or more generations older than you. You would use “primo” or “prima” to refer to most members in your same generational group. You would use “sobrino” or “sobrina” to refer to most members one or more generations younger than you. Considering the breadth of different relations that came attached to each of those generational labels within La Familia, “tía” only happened to translate to “aunt” occasionally. “Tía” just as easily meant “my spouse’s cousin’s sister-in-law’s godfather’s grandmother” as it did “my father’s sister.”

There was an additional kin term translation important to the transcript below that was even more incommensurable within La Familia’s assimilation to Mormonism than tía was to aunt. That kin term was hermanos (siblings). If you were a member of La Familia, you would use “hermanos” to refer to everyone in your same generational group with whom you grew up under one roof. Therefore, La Familia did not distinguish between half-siblings, stepsiblings, “full siblings,” and siblings by blood. It did not even distinguish between siblings, cousins, nieces, goddaughters, and uncles so long as all were the same approximate age and grew up in the same household, however loosely conglomerated. “Hermanos” included everyone raised together on the same food and drink in the same place. Peruvian parents, tíos, godparents, and grandparents carefully constructed the bodies of hermanos over time with the substance of locally grown, homemade food until those bodies consisted of the same amino acids as the earth’s bounty and as each other. That formulation made all into one related body in ways just as literal as the ways through which shared DNA naturalized kin within the idiom of blood.[23]

Yet, being a Mormon parent in addition to being a Peruvian parent, Jacoba considered herself as having at her disposal more building materials of siblingship than simply Peruvian cachangas (frybread) and apí (a sweet corn drink). As our conversation with Chalo around the campfire at Church-owned Camp Atoka, Utah in 2017 resumes below, Jacoba demonstrated the genealogical prowess that she mentioned in the epigraph. She reshuffled the substances involved in “growing up together” along with those of blood and tiny papers so that her sobrino Chalo’s daughter Leslie could become her daughter-in-law. In so doing, she revealed a fundamental difference between La Familia and forever family.

Chalo: So, I asked my tía Jacoba, “What does blood have to do with it?” I asked, “What do you mean that I’m not your blood nephew?”—

Jacoba: —And I admit that I was a little too blunt—I’m sorry, Sobrinito [Chalo]—but I felt it was better to just rip the Band-Aid off all at once. And the whole purpose was so that Leslie could marry Ammon—

Chalo: —and we both wanted that pairing to happen, so I wasn’t offended or anything, just shocked. Like, “Why had I not known this before?”

Jason: So, even though some of your hermanos were from different fathers and mothers, you never even suspected your whole life growing up with them that you didn’t share any blood at all with any of them?

Chalo: Never. Never suspected. And why would I? It’s not like I go around looking at my birth certificate every day. So, when my tía Jacoba showed me my birth certificate for the first time just last year, I was shocked. My father wasn’t on there! It was some other guy. I mean, I knew that my mother was a different mother from the ones who had birthed all of my other hermanos, but I thought that my father was Jacoba’s brother, and, it turns out, he wasn’t. He was just some random dude.— By the way, Tía, how did you procure my certificate?

Jacoba: I have my methods [laughing]. I have my genealogical abilities, and I wield them as I see fit.

Jason: And you saw fit to marry your son to Chalo’s daughter?

Jacoba: Correct. Very correct. And it’s best if those who marry are not primos, so if I could find a document to eliminate the blood, all the better.

. . .

Jason: So, Primo [Chalo], how did you feel to know that the hermanos with whom you had grown up weren’t really your hermanos?

Chalo: Well, that right there is an Anglo-Saxon way of thinking, Primo Jason, like we were just talking about. That question shows your gringo-ness coming out because of course they were still REALLY my hermanos. Some papelito isn’t going to change who my hermanos REALLY are. I mean, we had already grown up together. I was already an adult. The only thing that changed was that Leslie could now marry Ammon. So, it was mixed feelings: happiness for those two lovebirds and a little bit of an identity crisis for me. I’m not going to say that seeing my birth certificate for the first time as an adult had zero effect on me—

Jacoba: —Papelito manda, as they say.

Chalo: In my case, yes. I have lived papelito manda. [laughing] I am the very spawn of papelito manda!

Jacoba: No! [laughing] Riana [Ammon and Leslie’s daughter] is the spawn of papelito manda!— La Familia is a curious thing. Am I right, Sobrino Jason?

Papelito manda is a Peruvian adage that means “at the tiny paper’s command.” It expresses the simultaneous holiness and silliness of colonial statecraft’s obsession with diminutive documents, papelitos, such as birth certificates and visas. For early Spaniards in Tawantinsuyo—the name that the Incas gave to their empire in human language, or Runasimi—tiny papers with royal seals on them were literally the substances of the king of Spain’s bodily presence.[24] In a similar substance shift for early Peruvian Catholics, wheat hosts—as opposed to cornmeal hosts—in human mouths were literally the flesh of Jesus.[25] More recently, for the twenty-first-century Peruvian Mormon Jacoba, finding Chalo’s birth certificate literally rewired La Familia. Dates and names written on a certified papelito became potent enough to eliminate the blood of the incest taboo. That elimination allowed former primos to form a conjugal nuclear bond on Jacoba’s granddaughter Riana’s FamilySearch.org family tree, essentially fulfilling Phase Five of Jacoba’s construction of Leslie into La Familia.

Essentialist Blood versus Constructivist Drink

Essentialism is a cultural preference to consider reality as externally imposed, preexisting, static, and discoverable. Constructivism is a cultural preference to consider reality as constantly created and renewed by human and nonhuman volition and interaction. Chalo and Jacoba’s campfire discussion—which involved many other members of La Familia who chose to participate in what I staged as a digitally recorded focus group regarding the differences between what I termed “gringo family” and “Peruvian familia”—laid bare a difference at the heart of kinship between Peruvianness and Mormonism. Basically, Peruvian non-Mormon familias in my study were more constructivist while Mormon non-Peruvian families were more essentialist. Therefore, it stood to reason that people who were both Peruvian and Mormon, such as most members of La Familia, would tend to pick and choose between essentialism and constructivism as they, in Jacoba’s words, “saw fit.” Within pure essentialism, kinship is a discoverable mechanism of unidirectional inheritance connected to people’s biological essence as reproductive mammals. Within pure constructivism, kinship is a chosen reciprocity requiring the cyclical, multidirectional flow of nonheritable substances. Though official Mormon kin systems were lived in both essentialist and constructivist ways,[26] Mormonism expressed essentialism through its dogma that the essence of family could only take two possible forms. For the official Church during my study, “real” kinship was either legal or genetic. Those two forms could be diagrammed with horizontal equal signs signifying sexual intercourse and vertical lines stemming from that intercourse signifying its offspring (figure 3). The vertical lines also symbolized the kin idiom of “blood” similar to the late-Medieval European arboreal charts of vertical descent wherein named, individual ancestors fell above, meaning chronologically before, “descendants” who multiplied exponentially, increasing their individuality across distinct, numbered generations as they moved away (down) from their ancestors toward the future.[27]

The essence of LDS forever family during my study only came into being through the meeting of signatures on legal marriage/adoption certificates or through the meeting of gametes in uteruses. Both such meetings could be documented onto papelitos. Within such an essentialist kin system, legal documents and genetic tests involved knowledge that was understood to be discoverable and, whenever it was newly discovered, as existing prior to and regardless of the relationships that the documents and tests supposedly proved. Therefore, Chalo hearkened to essentialism when he expressed that his relationship to his tía changed based on new knowledge. Written knowledge of “some random dude” whom Chalo had never met much less constructed as “father” through commensality (eating together) was strong enough to eliminate blood between him and his tía. However, Chalo simultaneously hearkened to constructivism when he scorned my “gringo” way of thinking. Chalo felt that the new knowledge expressed in a tiny paper could not make the relationships that he had painstakingly built over decades with his hermanos any less real. His siblingship suddenly lacked the essence of Mormonism’s forever family—DNA and state documents—but it sustained itself through the work of kin construction that he and La Familia had established utilizing food and drink in place and over time.

Individualist Papers versus Collectivist Food

The stage was now set for Leslie’s official addition to Jacoba’s grandchild’s family tree. Therefore, Phase Five of Jacoba’s construction of Leslie into a relative within La Familia was complete. Only two phases remained. Those two phases—Phase Three: Utah Immigration and Phase Six: Temple Sealing—were complexly intertwined within Jacoba’s imaginative kin-building endeavors. Though an understanding of those complexities required Jacoba’s explanations, some parallels within the intertwinement were strikingly self-evident. For example, I could easily see the procedural similarities between LDS temple sealing and US immigrant petitioning. Both resulted in permission to enter places made holy through the elimination of certain elements considered profane.[28] Both required interviews wherein interviewers tried to discern the inner worthiness of their interviewees.[29] Both measured worthiness “in terms of assimilation”[30] to US whiteness. Both sometimes resulted in papelitos, be they temple recommends[31] or immigrant visas. Most of all, both were based on the same root kinship system that only considered a handful of “direct family members”—relatives with certain biologically or legally documentable kin connections—to be sealable and petitionable.

However, there were internal similarities between the LDS and the USCIS (United States Customs and Immigration Services) that were less obvious. Jacoba often tried to explain to me the complexity of how LDS temple entry and US border crossing were both part of the same kin construction process. As I understood it, if Jacoba had not met a missionary from Utah in New Jersey in the 1970s, her young nuclear family would have never migrated to Utah. Had she never migrated to Utah, she would have never included temple sealing as a requirement for family-building. Had she never granted importance to temple sealing, she would not have worried so much about finding temple-worthy[32] mates for her children. Had she not worried about temple worthiness, she would not have helped Leslie and her father Chalo convert to Mormonism. Had they not converted to Mormonism, Leslie would not have been worthy of Ammon. Had Leslie not been worthy of Ammon, Jacoba would not have staged a pre-wedding reception for them in Peru—complete with the vital Peruvian kin substances of dance, food, and drink—in order to procure papelitos, photographs, and affidavits from attendees to present to USCIS officials at the embassy in Lima as proof of her future daughter-in-law’s US-worthiness for a fiancé visa. Jacoba would not have known that she needed to worry that the USCIS might contest Leslie’s US-worthiness had Jacoba not extralegally rearranged La Familia countless times prior so that the relationships of its would-be immigrants could become legible as “direct family” in the exclusionary kin system that structured the USCIS. Finally, she would not have become adept at making La Familia seem legible as family within the USCIS kin system had she not continually made similar adaptations within a kin system that was coterminous to that of the USCIS: the kin system of the US LDS.

Therefore, navigating the USCIS legalese in order to gather La Familia into one terrestrial place—an action vital to La Familia’s place-based commensality and earthy cycles of rhizomatic relatedness—was inextricable for Jacoba from her navigation of the LDS templar rites carried out in that place. That place was Utah, and its temples promised to eternally solidify each individual relative’s placement onto her family tree. Though convoluted to an outsider, for Jacoba, the inextricability of LDS kin notions from USCIS kin notions made perfect sense. For me, an anthropologist, that inextricability seemed to radiate from another kin system dichotomy in addition to “constructivism versus essentialism” that Jacoba’s Peruvian Mormon kin-building melded into one: “individualism versus collectivism.”

The best vantage from which to witness individualism and collectivism melt into one indistinguishable relatedness through the substance of tiny papers was inside the Mormon temple. During part of my anthropological fieldwork in 2017, I became a “temple worker” inside the Ogden, Utah temple. I participated with both Anglo and Peruvian Mormons as they conducted religious rituals wherein the kinship bonds that they felt to be scientifically verifiable through papelitos were “sealed,” thus making their mortal families into what they called “forever families.” They called this process “temple work,” and it also involved homogenizing and “nuclearizing” the world’s diverse kin models, past and present. The “nuclear family” is a kinship form that generates itself as a novel, individual unit when a husband legally marries a wife. In other kin models, such as the “conglomerative family” popular in Peru, two existing households combine when members of those families marry. Conversely, in the nuclear family, a brand-new household is formed, and the conjugal couple becomes its center, its nucleus. The nuclear family household ideally consists solely of the couple and its biological or legally adopted minor children who, when they come of age, form their own, new, distally dwelling nuclear families, leaving the original couple with an “empty nest.” Though the nuclear family was the globe’s least valued kin model during my study,[33] it was the only kin model that the famously global LDS Church valued enough to include in its templar sealing rituals. Indeed, only two types of relationships could be eternalized in LDS temples in the late 2010s: husband-wife and couple-child. Temple work, therefore, was akin to US immigrant exclusion work. It was the work of rescuing ancestors from their diverse, non-nuclear conglomerations of relatedness and enclosing them into limited dyads.

In November 2017, I participated with Jacoba in marriage sealings for an unknown third party’s dead relatives. In the sealing ceremonies, which lasted about two minutes for each marriage, I was proxy for the dead grooms and Jacoba was proxy for the dead brides. In an interview that night at her daughter’s home, Jacoba interpreted the sealings that we had performed to mean that celestial bureaucrats living on a temporally distant but spatially proximal planet made of “spirit matter” were writing the new conjugal kin relationships down on papelitos bound into the book of heaven. Indeed, using white pens and white clipboards, I had often observed temple registrars keeping carbon copies of that book of heaven inside white, three-ringed binders housed in the temple’s white filing cabinets. According to one registrar whom I interviewed in August 2017, the substance of the papelitos inside those earthly binders adhered to corresponding little papers in heaven. The resulting glue bound husbands to wives, children to parents, and eventually descendants to their individualized “direct-line ancestors” so that those relationships could remain valid even after the biological or legal deaths of the individuals who embodied them on this planet.

During the templar ritualizing of these bureaucratic kin validations that I observed, living Mormons often played the ritual role of themselves. However, the role of their ancestors was played by tiny papers, about two inches long, that were coded blue for male and pink for female. Each blue and pink papelito included a dead individual’s—as opposed to a live collective’s—name, death date, birth date, and birthplace. Those papelitos exemplified one of the few non-white color schemes in the temple’s meticulously whitened interior design,[34] logics,[35] and habitus.[36] The color contrast highlighted the temple’s pervasive whiteness, symbolically linking its kinship bonding to US immigration law’s project of racial whitening.[37]

During my study, Anglo Mormonism’s templar project—just like US immigration law’s demographic project—held biogenetic kinship unquestioned as a “fact”[38] that was simultaneously scientific, religious, and racial.[39] As anthropologist Marilyn Strathern recognized in England, which loaned early Mormonism many of its kin notions, “genetic relations have come to stand for the naturalness of biological kinship.”[40] That naturalness, expressed in the unquestioned embodiment of individualized “blood” ancestors inside the templar substance of color-coded papelitos, represented the ways in which European cultural hegemony—whiteness—placed biogenetic data “outside of culture”[41] for the Anglo-dominated LDS Church as if that data transparently reflected “a universal biology without cultural mediation.”[42] Therefore, thinking temple work to be without a situated historical and cultural context, Anglo Mormon Church leaders have applied biogenetic kinship to the entire world through their global temple-building project.[43] Through temple rituals and their white-pigmented architectural reinforcements, the Church cloaked its culturally situated, constantly evolving kin system inside a white shroud that made what was essentially the white nuclear family of 1950s suburban Utah seem globally applicable, eternally unchanging, and seductively mysterious.[44]

However, Jacoba, along with many of my Peruvian Mormon study participants, considered the individuality of ancestral genetics expressed on templar blue and pink papelitos to be no more factual than the myriad other substances through which their overlapping societies gauged relatedness. Many felt, along with the Zumbagua of Ecuador,[45] that children were more legitimately related to the collectives with whom they shared homemade food on a daily basis than they were to the two individuals who gave them half of their chromosomes at the single moment of conception.

Scholars of Indigenous Mormonisms Arcia Tecun and S. Ata Siu’ulua[46] wrote about clashes between individuality and collectivity within another of the world’s Mormonisms, that of Tonga. When Anglo Mormon missionaries first arrived on the island of Tonga, the language of Tonga had no word to express the idea of an individualistic, distantly dwelling, husband-centric, heteropatriarchal, ostensibly monogamous couple and its coresident minor offspring. Anglo Mormons had to loan them the word for such a thing. The word was “family.” Runasimi-speaking philosopher Conibo Mallku Bwillcawaman (who has published under the name Ciro Marín Benítez)[47] also wrote about incompatibility with individualism in the case of people living in twenty-first-century Tawantinsuyo. The US settler state’s linear blood descent—upon which the official Church’s genealogical strictures were patterned for the temple sealing of dead ancestors and upon which the USCIS definition of “direct family” for the purposes of Peruvian immigrant visa petitions was likewise patterned—made no sense in Tawantinsuyo’s collectivist, nonlinear, ungendered, rhizomatic (as opposed to arboreal) system of relatedness called pacha.

In Bwillcawaman’s conception of Runasimi philosophy, pacha meant both “earth” and “communalism.” Therefore, it encapsulated the incommensurability that my Peruvian American teenage study participants sensed between family and familia. Pacha was Jacoba’s Phase Four of kin-building. It involved constructing human and nonhuman individuals into one collective cycle wherein antecedents and descendants lost their arboreal verticality and became one place-based whole.

Making Hermanos with Blood, Food, Drink, and Papelitos

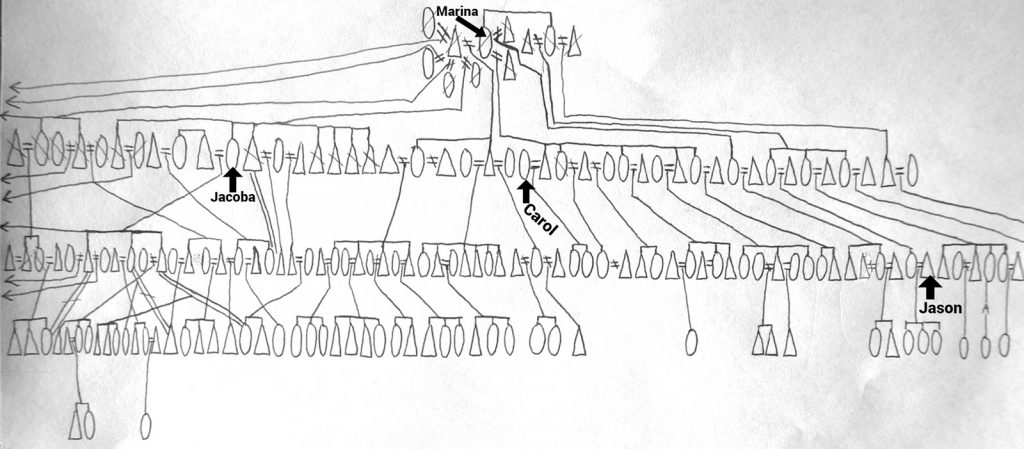

Yet, as a testament to Jacoba’s “genealogical abilities”—perfected through her Mormonism—the expansive pacha relatedness that was La Familia could also be expressed as an arboreal diagram. It took Jacoba and me hours of conversation and artistry to force the collectivist complexity of pacha familia into the papelito of individuality depicted below (figure 2). That diagram will become useful in moving the discussion of Jacoba’s kin-building toward relationships beyond that of her daughter-in-law Leslie. The Utah version of Leslie and Ammon’s pre-wedding celebration became a venue for Jacoba to wield all of her kin substances—blood, food, drink and papelitos—to enforce Phase Two: Mormon Conversion and Phase Six: Temple Sealing, onto both a living new member of La Familia—Carol—and onto a deceased founding member of La Familia—Mamá Marina.

As depicted below, La Familia was a group of mostly Peruvians and mostly Mormons. Jacoba led a faction of La Familia whom her suburban, Anglo Mormon, nuclear-family-home-dwelling neighbors knew as The Costa Family. During my study, more members of La Familia immigrated each year from Peru toward the rhizomatic rootstock of its Utah node in the upwardly mobile, pseudonymous city of Salsands, where over 150 members of La Familia dwelled.

Figure 2. An arboreal expression of a small portion of La Familia.

| = Conjugal relationship | ⎴ Siblingship |

| / Offspring of connected relationship | // First cousin once removed marriages and other intergenerational coupling |

| ≠ No longer together | |

| △ Male | |

| ○ Female | Ø Deceased |

That rootstock was not discovered through papelitos. It was not a biologically “natural” occurrence that people just happened to be “born into” or that I was able to join by simply “marrying into.” Even after being sealed to one of its daughters in the Salt Lake City temple—the holiest of Peruvian Mormon places on this planet—it took me sixteen years to become part of the substance of La Familia. I had to be built into it. While that did require papelitos like marriage certificates and genetic substances like chromosomes, it mainly required other substances: Peruvian food and Peruvian nonalcoholic drink—Inca Kola—shared in proximity through Peruvian Mormon partying. I did not experience that proximity, that commensality, that pacha with the Costa faction of La Familia until 2014 when I started to anthropologically study with La Familia and when Jacoba started to connect me to its rhizome.

That Jacoba would construct La Familia as a rhizome rather than a tree might seem contradictory given that La Familia was largely Mormon and that Mormons were famous for their obsession with an arboreal model of kin descent wherein ancestors gave of the substance of relatedness, DNA, to their descendants and wherein such sharing of substance never happened in reverse as it would in a rhizomatic model. Contradictory as it may be, though Jacoba was Mormon and had lived in a middle-class, Mormon, Utah city for decades, she still retained parts of a cyclical ancestral idiom from Tawantinsuyo that complicated the individuated family. When she talked to me in November 2017 of her ancestors, she tore the hegemonic arboreal analogy of Western European genealogy apart at the middle. She said, “I always tell human beings: ‘Look. Plant. Your kids are your branches, and your grandkids are your roots. And they remain there, planted.’”

As a Mormon, she had seen countless “family tree” depictions wherein grandchildren fell below children. Those trees sprouted individual ancestors as branches and individual descendants as roots. Yet, Jacoba placed descendants (kids and grandkids) as both the branches and the roots: the future and the past. Hers, therefore, was a rhizomatic web of pacha familia, not a family tree. Children could give parts of themselves to parents, making parents descendants as much as antecedents. Jacoba’s rhizomatic model made humans into “dividuals”—beings that could be divided among one great whole—rather than individuals.[48] Furthermore, since her cyclical cosmovision had only somewhat to do with genetics and vertical blood descent, nonblood kin, such as myself, who gave and took of the substance of relatedness and coresidence could become dividuals within Jacoba’s genealogy provided we pass through all six of her kin-building phases, including Phase One: Becoming Sufficiently Peruvian.

To provide a microcosm of the substances that Jacoba used to construct rhizomatic relatedness among La Familia and the constant work required to maintain its layers of mutual indebtedness, I provide below an ethnographic vignette from one of the many Peruvian Mormon parties that built me into a Peruvian of sorts and that lubricated the cycles[49] that held La Familia together. The relationships within La Familia were never taken for granted as they would have been had they been purely essentialist. Since they were based on perishable substances like food and drink, not simply on archivable substances like genealogy and papelitos, they required constant work to keep from expiring. The festivities in question took place in the up-and-coming, exclusive suburban city of Salsands, Utah. However, before offering a glimpse into the party, I must first provide more background on the party’s protagonist.

Jacoba immigrated from Lima, Callao to New Jersey in the 1970s with her husband Arcadio Costa, moved to Utah because of a business proposal by an Anglo Mormon missionary, became a Mormon, and—infused with a material substance that Mormons call the “spirit of Elijah”—started doing her genealogy. This involved making her first creative attempts at mixing kin media and substances. According to the aforementioned interview that she granted me in November 2017, one of those substances included volitional spirit matter. Jacoba’s ancestors’ spirit bodies periodically appeared to her. These apparitions wrote dates using ballpoint pens—with the substance of ink—on the previously blank backs of photographic depictions of their former selves printed on papelitos. Jacoba combined this ghostly data with information from cemeteries and Catholic parishes in Peru until she understood herself to be the indirect byproduct of one of three sexual relationships between a woman whom all members of La Familia called Mamá Marina and three men, one of whom, Jacoba’s father, had at least thirty-six children among four women, another of whom was Jacoba’s mother.

This complex mix of unwed polyandry and polygyny produced multiple layers of siblingship that Jacoba would devote most of her life to sifting out and “dividualizing” into hermanos within a European diagram of genealogy (Phase Five). As she investigated these hermanos, she did not segregate them into the European kin groups of “half-sibling,” “stepsibling,” or even “cousin.” Even though she had only grown up with a few of them and did not know about the existence of most of them, all were equally “hermanos” in her understanding of relatedness, and she sought them through return trips to Peru. Since they were already Peruvian—Phase One—she constructed her hermanos as Mormon—Phase Two—through fusing Inca folklore with Lamanite dancing.[50] Lamanite dancing was a complex assemblage involving a unique form of Mormon Indigeneity—Lamanite identity—derived from the fact that many Latin American Mormons considered the setting of the Book of Mormon to have been ancient Abya Yala,[51] thus making their own ancestors into the heroes of Mormonism’s origin myths.[52] Jacoba often solidified the nascent Mormonism within her hermanos by sending, both officially and unofficially, herself, her children, and her Utah-born grandchildren on LDS missions to specific parts of Peru in order to baptize them. Incidentally, Jacoba’s daughter Lori was the one who, at Jacoba’s behest, sought out and helped my future mother-in-law Nilda convert to Mormonism in 1984. During all aspects of her kin-building, Jacoba carefully wove her hermanos into La Familia through Peruvian cuisine and pacha commensality (Phase Four). Furthermore, she brought many of her newly deemed hermanos to Utah (Phase Three) so that the proximity requirements of pacha could be met, thus cementing her hermanos almost completely into La Familia. “Almost” refers to the lack of the ultimate step—Phase Six: Temple Sealing—but, as that resulted in a family feud microcosmic of the substances of La Familia’s simultaneously Mormon and Peruvian systems of relatedness, I will save it for the end.

For now, returning to Phase Three in Jacoba’s methodical creation of La Familia, in order for Jacoba to bring her siblings to the United States in the first place, she usually had to temporarily rearrange Peruvian pacha into US kinship so as to appease the USCIS requirements of “direct family” on her hermanos’ immigration papelitos. This was necessary because many of her “hermanos” did not compute as “siblings” under US colonial statecraft. Members of La Familia who were biogenetically “cousins” to each other, and thus not petitionable for US immigrant visas, became—through staged marriages and the papelitos that these produced—“husbands,” “wives,” and “stepmothers” to each other. All of those kin categories were petitionable under the narrow confines of what got to count as “family” in the United States. Importantly, those confines were not nearly as narrow as the Anglo Mormon confines of “family” that dictated which relationships could be immortally sealed in the temple. It bears repeating that, during my study, only two types of relationships could be officially sealed into forever family: husband-wife and couple-child.

Everyone Is Sealed Except You

Eventually, much of La Familia’s construction got out of Jacoba’s control and went on without her knowledge. Thus, one of her sobrinos whom she helped immigrate helped one of her unknown, nonblood hermanos immigrate to Utah. Biogenetically, that hermano was Jacoba’s half-sister’s half-brother. His name was Mido, and he immigrated together with his wife Carol in 2001. Jacoba met Mido and Carol for the first time during my fieldwork at Mamá Marina’s Utah funeral in 2016. At the July 2017 party that I will now finally depict, Jacoba tried to build Carol into La Familia in ways that revealed Jacoba’s uniquely Peruvian Mormon understanding of the substances that created pacha familia for her.

The occasion was Ammon and Leslie’s wedding shower/housewarming party. Ammon and his newly immigrated Peruvian fiancée, Leslie, were moving out of Jacoba’s daughter’s large, crowded home where the party took place and into their own Salsands apartment down the street, right next door to me and my nuclear family. Therefore, they needed household supplies. At first, the decibel level was high, with every group in full conversation mode eating at their respective collapsible tables, which La Familia had borrowed from our local LDS chapel. Jacoba was over on Leslie and Ammon’s table with many of Los Tíos. I could see that she was dominating the conversation there.

Another table held the native English-speaking generational group known as Los Primos, which included eighteen eligible single ladies, some in near-spinster status on Mormon timelines, meaning that they were almost age thirty-one. Los Primos mostly included Jacoba’s biological grandkids, but it also included the Corimayta siblings who had been adopted as Jacoba’s grandkids because their real grandparents died in Peru without ever meeting them. Since the death of Mamá Marina one year prior, Los Primos also included Mido and Carol’s daughters Luzi and Zelma, who were still navigating their recent inclusion into the Costa faction of La Familia. The tables of Los Primos included many people whom I did not know at the time. Some of them were Ammon’s kids from his multiple previous relationships. Then there was the “primitos,” or little cousins’ table. That consisted of Ammon and Leslie’s daughter Riana, my three daughters, and Ammon’s youngest son from a previous relationship. They all ate cachangas for two seconds and then jumped on the neighbors’ trampolines for two hours. In that neighborhood, the entire backyard row of at least seven houses did not have any fencing, so the upper-middle-class neighbors shared each other’s well-grassed yards.

After the housewarming gift-opening proceedings, Ammon and Leslie each gave a little speech. I noticed on a few occasions that Leslie would correct people when they said “your husband.” She would say, “No, my FUTURE husband.” Jacoba was also careful to make that correction. The confusion surrounding the tense in which to conjugate the verb, “to marry” probably existed because everyone at the party knew that Ammon and Leslie had long ago consummated their conjugal relationship (even before they found out that they were not biological primos), the offspring of which, Riana, jumped on a distant trampoline as they gave their speeches. However, the confusion also stemmed from Ammon and Leslie’s large “false” wedding in Peru, which Jacoba herself organized. Many of the housewarming party guests apparently did not know that Ammon and Leslie’s “Peruvian wedding” was not legally officiated. In the United States, it would have been considered more a reception than a wedding, and it was all part of Jacoba’s scheme to generate enough affidavits and photographs to prove to US embassy officials in Lima that Ammon and Leslie’s conjugal relationship was founded on love, which the USCIS kin system considered legitimate, rather than on the desire for a visa, which the USCIS kin system considered illegitimate. Jacoba’s maneuvering ultimately helped Ammon procure a fiancée visa for Leslie. However, during the party in Utah, Ammon and Leslie still held no tangible marriage certificate valid in the United States or Peru, much less a temple marriage certificate valid in the celestial kingdom. Therefore, a linguistic confusion lingered among the guests, reflecting the mix of kin systems under which Ammon and Leslie were simultaneously married and not yet married.

Following their speeches came the requisite Costa Family dance-off. It was similar to the one that I had endured three years prior in order to prove my Peruvianness. On this occasion, however, rather than judging the contest as she had done during my choreographic ordeal, seventy-five-year-old Jacoba, a Peruvian Mormon, sat on the couch having a fervent conversation with fifty-five-year-old Carol, a Peruvian Catholic. Jacoba held Carol’s hand the entire time. I tried to listen in on their conversation between huaynos, cumbias, sayas, and merengues, but all I heard were a few key words from Jacoba. She seemed to be laying it on pretty thick, saying things like, “You are not sealed to your ancestors” and “What comfort it brings me to know that I am.”

Making out the words “sealing,” “intertwining,” “bonding,” “interlacing,” and “joining,” I was sure that a significant kinship conversation was afoot. However, when Los Primos got ahold of the sound system, the reggaeton became too loud for me to hear anything else. Fortunately, later, when almost everyone was gone including Carol, all the collapsible tables were down, and Jacoba and I sat alone at the oak table. I asked Jacoba what she had talked about with Carol. She had no qualms telling me. As I suspected, in her conversation with Carol, she had jumped right into the topic of familial sealings. I asked her permission to turn on my digital recorder.

Jacoba: First thing I told her was, “Carol, you aren’t sealed, so you really aren’t yet a member of La Familia. How would you like to be resurrected, as we are all going to be, and have Jesus meet you and say, “Go over to this kingdom of strangers that I’ve prepared for you and be an angel with other strange angels for eternity without ever seeing your family again”? Well, that is what is going to happen if you don’t get sealed.

Apparently, Jacoba never once mentioned to Carol what sealing meant, where it took place, what had to happen first, or how sealing historically came about in the LDS Church. Instead, she held all of that in her head as a given of the Mormon cosmos and talked as if Carol were already fully a part of that cosmos but that, for some unfathomable reason, she just did not want to be together with La Familia—her in-laws—for eternity. I told Jacoba, who had only recently met Carol and who—according to Anglo Mormon arboreal genealogy—was not related to Carol’s husband Mido at all: “I know from talking to Carol over the years that she has never heard of any of this before. She genuinely doesn’t know about eternal sealing and forever family.”

Jacoba responded, reprimanding me: “How is that possible? Carol has been in Utah for fifteen years. With all the returned missionaries that we have in La Familia, including you, Sobrino, why did nobody tell her?”

I hoped that was a rhetorical question, but it was not. She expected an answer from me.

Jason: Well, maybe nobody told her because until recently she’s worked three jobs all day and so even the faction of La Familia that knew about her hardly ever saw her. Also, maybe nobody told her because they know that she is extremely Catholic. She actually goes to mass almost weekly.

Jacoba: I know that she’s Catholic, and I told her, “I was once like you. I was Catholic too. My kids all went to Catholic schools, but that was before I knew the reality of things. I mean, think about how bad the Catholic Church has been! Think of what the Inquisition did in Peru. And who did they persecute? Those who wouldn’t worship the cross. And who were they? The Incas, our ancestors. And we who are Lamanites know that the Incas were Christians. They had the truth already, and the Catholics took it away from them and killed them for not worshiping the cross. But why would you worship a cross if your son was killed on a cross? Would you worship that instrument of death, wear it around your neck?”

I had difficulty believing that she had said all of that as Carol sat right next to her with a tattoo of that very cross emblazoned onto her bare shoulder. Nevertheless, Jacoba continued her tirade.

Jacoba: Then I said, “It is a disgusting instrument of death, and you want to have it ON you!?”

Carol just kind of laughed it off and didn’t know what to say. What she didn’t realize was that none of the people at the party today would have come to this country anyway if it weren’t for me. They wouldn’t be members of the [LDS] Church and we wouldn’t be sealed if it weren’t for me. I was chosen for this work. “You wouldn’t be here in this country if it weren’t for me,” I told Carol.

“I wouldn’t have found out my other brothers like your husband Mido if I hadn’t joined the Church and realized the importance of joining all the family unit into one. That is why I searched out my long-lost sisters, which led to Nilda coming here, which led to you—Carol—coming here, and now it is up to you to be the last link in this chain. You must be sealed to us or else La Familia isn’t complete. You have to carry on my mission, because mine is ending, but yours is just beginning. That is why you are in this state of Utah. It’s not a coincidence that you are here. Things happen for a reason. The only church with the power to seal brought you here, and now, if you care about your ancestors at all, you will be sealed to them. How can you be so ungrateful as to not be sealed in the temple of the very religion that in a roundabout way brought you to me, brought you under my circle, which is sealed? Everyone is sealed into this circle except you. La Familia can’t be saved without you.”

Familia Feud

I reminded Jacoba that getting sealed in the temple was supposed to be the final, not the initial, phase toward familial salvation, at least not in the unilinear progression model of Anglo Mormonism in which I was raised and which made the templar rules for all members of the Church the world over regardless of which substances granted them relatedness. The first step for Carol in Anglo Mormonism—the hegemonic form of Mormonism—would have had to have been baptism (Phase Two), making baptismal water into yet another substance of relatedness for La Familia. However, Jacoba talked as if Carol’s presence upon the ground of Utah (Phase Three) qualified her to be sealed to La Familia without even being baptized a Latter-day Saint in the first place.

I also reminded Jacoba that it was not true that Carol was the last unsealed link on La Familia’s circular chain, the circularity of which was another difference in symbolic substance—this time metallic—between Peruvian Mormon circular relatedness and Anglo Mormonism’s great linear chain of being. Carol may not have been Mormon-temple-married (sealed), but Mamá Marina, the foundational matriarch of La Familia, was never married at all. This left La Familia’s relatedness—inasmuch as it depended upon templar papelitos in three-ringed binders that needed to be cosmically sealed to celestial tomes—vulnerable to schism. Jacoba witnessed that schism widen soon after Mamá Marina’s death and, during Ammon and Leslie’s party, Carol became its scapegoat. Jacoba projected Mamá Marina’s foundational lack of sealability solely upon Carol. In reality, however, Carol was not the salvatory embodiment of La Familia’s relatedness. She was not the last unsealed link. She was not the severed rhizomatic rootstock.

That role fell squarely upon the recently deceased Mamá Marina whose dying wish, at the age of ninety-four, was to not become posthumously Mormon through a templar “baptism for the dead.” Only Mamá Marina, La Familia’s symbolic matriarch who crowns the genealogical diagram (figure 3), could heal the familial schism. Only Mamá Marina could somehow suture heaven and earth despite her lack of three vital Mormon substances of relatedness: baptismal water, DNA shared with Jacoba, and templar papelitos.

La Familia’s schism did not begin with Mamá Marina’s apparent unsealability, but it was exacerbated by it and by Anglo Mormonism’s kin strictures. In the Anglo Mormonism of the late 2010s, families had to wait for one year after the death of a non-Mormon ancestor in order to do the following “temple work” for her by proxy through the aforementioned pink papelitos:

- Baptize her into the Church.

- Temple-marry her to her spouse.

- Seal her children (living or dead) to the resulting nuclear couple.

Since Mamá Marina never had a spouse, La Familia was left with the same question that plagued other Lamanite-identifying familias as early as the 1920s, when Mexican Mormon Margarito Bautista first began interpreting Anglo Mormon templar esoterica for use within Indigenous Mormon systems of matrilineal relatedness: “How was a woman who had never been married but who had been the mother to many children to be permanently linked into a nuclear family unit in the eternities?”[53] Male ancestors could be forced into eternal polygyny, that is, they could be sealed to more than one wife. However, female ancestors, like Mamá Marina, could not be sealed to more than one husband (at least not according to the many Anglo Mormon temple presidents whom I queried at the behest of La Familia).

Since the one-year anniversary of Mamá Marina’s death arrived soon after Ammon and Leslie’s housewarming party, Jacoba’s feelings regarding La Familia’s sealability were not the only ones that exploded. During this schismatic time of heightened sentiments, which became particularly volatile from 2017 to 2021, one faction of La Familia worried about the righteousness of posthumously sealing (temple-marrying) Mamá Marina to any of the three deceased men with whom she had “lived in sin” (had children out of wedlock). At La Familia’s Christmas party in December 2017, the unofficial spokesperson of that faction asked, “Wouldn’t sealing her to any one of our abuelos mujeriegos (womanizing grandfathers) condone polygamous promiscuity, making a mockery of the Lord’s temple?” Anticipating a resolution to that question, another faction asked an adjacent question, thus fracturing La Familia further: “To which of the three men should Mamá Marina be sealed?” Carol and Mido’s faction, being Catholic, did not want her sealed in a Mormon temple at all, a sentiment that they did not dare share openly. Members of most of La Familia’s Mormon factions, on the other hand, openly advocated for Mamá Marina’s posthumous temple marriage, but only to their own paternal ancestor. However, they all wondered as to the exclusivity and irrevocability of such an act: “Will sealing Mamá Marina to just one man leave the biological descendants of the other two men cut off from La Familia for eternity? Why not seal her to all three men?” During my study, eternal polygyny was officially acceptable in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, famous as it was for its obsession with patriarchy and marriage, so why could La Familia not get special permission from an Anglo Mormon temple president to perform just a bit of eternal polyandry?

Biospiritual Husbandry

These were vital questions for Jacoba given that she was constructing La Familia with the substances of both patriarchal, settler Mormonism (blood and tiny papers), and generational, pacha matriarchy (food and drink). If Jacoba could not figure out how to posthumously seal Mamá Marina to a husband, then Mamá Marina’s children would not be able to seal themselves to her or to each other. Would those children—including Carol’s husband Mido, my mother-in-law Nilda, and my spouse’s “biological” aunts and uncles, not to mention our many tíos and tías including Jacoba herself to whom Marina was not related through the substance of DNA—remain an unlinked relatedness of expansive pacha familia simply because of Anglo Mormonism’s narrow, linear definition of “forever family” dependent entirely upon papelitos?

Not if Jacoba had anything to say about it. Unbeknownst to Nilda and Mido, Jacoba went on to have Mamá Marina posthumously baptized Mormon in the Ogden temple in January 2019. Jacoba then sealed Mamá Marina to all three womanizing fathers of her children in three different temples (Ogden, Lima, and Bountiful) so that no Anglo Mormon temple registrar—and presumably no celestial bureaucrat—would catch the mistake until it was too late. She even sealed Mamá Marina to one extra husband for good measure. He was one with whom Mamá Marina could not have “lived in sin” because she did not know him in life. Also, since he was a bachelor from Jacoba’s own biological, maternal line of arboreal ancestry, his coupling with Mamá Marina biospiritually linked Jacoba’s line into La Familia, legitimating Jacoba as La Familia’s new, regnant matriarch. All of this relational intertwining set the stage for a new existential controversy. Among her four new husbands, which one will Mamá Marina choose as her resident husband with whom she will situate Lamanite pacha through the cachanga-eating, Inca Kola–drinking, and Valicha-dancing festivities of the celestial kingdom?

Broader Impacts

That question encapsulates the substances of Jacoba’s multimedia creation of relatedness. Her creation was neither Peruvian nor Mormon in a framework wherein “Peruvian” stood for collective constructivism and “Mormon” for individualistic essentialism. Yet, her creation was fully “Peruvian Mormon”; it manipulated time and flipped ancestry in a way that blurred the boundaries between constructivism and essentialism, between individualism and collectivism. Jacoba created a temporality that allowed descendants to share the substances of relatedness with ancestors. Therefore, her Peruvian Mormon temporality—the same temporality that allowed her ancestors in Abya Yala the anachronism necessary to become the main characters of a US colonial text, the Book of Mormon—skirted any remaining barriers within her unlikely translation of familia into family. Jacoba’s kin-building shot holes into the supposed universality of Anglo Mormonism’s forever family. She made the forever family porous. In so doing, she revealed the nuclear family to be incoherent outside of Anglo Mormonism. She exposed the nuclear family as an empty, even nonsensical ideal toward which it was futile to strive.

The fact that Jacoba’s kin-building ran into resistance from her church’s leaders exposed the true purpose of Anglo Mormon temple work. Its purpose was to force “familias” and other rhizomatic, collectivist, and conglomeration kin models into the limited, heteropatriarchal, dichotomous, nuclear family model. The leaders of the Church came to consider the essence of true kinship as that which could only be found within the relatedness linkages between a husband and a wife and between a couple and its offspring. Temple work, therefore, represented the circumscribing of expansive kinship systems across world geography and world history into an atrophied kin system limited to a specifically conjugal and parental relatedness that was important mainly among Anglo Mormons raised in 1950s Utah. Temple work was meant to impose holy order upon the unwieldy, sacred, rhizomatic models of familia wherein ancestors were collectives that provided the substance of the future just as much as the essence of the past. Anglo Mormon temple work—saturated in white decor—sought couples and sealed them to children who were in turn sealed to their spouses in a model wherein everyone became trapped within a single, straight line leading back to a white Adam and a white Eve under the banner of a church named after a white Jesus whom anthropologist Arcia Tecun described as a “White perisex cisgender heterosexual wealthy”[54] Jesus.

Therefore, within the theoretical field that Jacoba’s kin-building exposed—though certainly not within the voiced opinions of Jacoba herself—Anglo Mormonism’s kinship individuality and kinship essentialism were racist. Connecting genealogically to the narrow, Adamic line of white ancestry was the only way for Saints of color in my study to legitimate their relatedness. Essentially, to become Saints, they had to become white.[55] All ancestral substances that could not be forced into white lineages had to be “silenced or erased.”[56] This meant that Anglo Mormonism’s kinship strictures, like most aspects of Anglo Mormonism, were not innocent.[57] Rather, they were colonizing.[58] Jacoba’s work in melding La Familia with forever family was not done on an even playing field. La Familia of Peruvian Mormonism found itself in a profoundly disadvantaged position in comparison to Anglo Mormonism’s forever family. The mere fact that Jacoba had to struggle so creatively to skirt Anglo Mormon kinship barriers revealed them to be precisely that: deliberately placed barriers, not merely benign differences. Her kin-building exposed the lie behind Anglo Mormon temple work. It was never meant to seal the whole human family into one universally inclusive siblingship as it claimed. Instead, it was meant to atomize the world’s relatives into tidily connected, easily diagrammable, nuclear dyads wherein all humans, past and future, could become listed, taxonomized, controlled, divided, and, therefore, exploited. In this, the settler Church treated its subjects no differently than the settler states treated theirs.[59]

Perhaps La Familia sensed a racist tendency within Anglo-connected Mormonism, though they rarely voiced it during my study. Perhaps sensing that racist tendency was why La Familia was relentless in replacing aspects of the Anglo connection to Mormonism with a Peruvian connection. Perhaps that was why Jacoba only brought into La Familia those who had shown themselves on the dance floor and dinner table to be sufficiently Peruvian while also placing themselves in Utah long enough to be sufficiently Mormon. For Jacoba, Mormonism had to be Peruvian for it to be correct because, according to her interpretation of the Book of Mormon, Peruvianness was Mormon to begin with. Jacoba went back in time and placed a simultaneously rhizomatic and arboreal form of Indigenous—yet colonial—Mormon kinship into Peru’s primordium. Thanks to Jacoba and other Lamanite Mormons like her,[60] an essentialist, individualist model of kinship has been made to coexist alongside constructivist, collectivist pacha among Abya Yala’s first human inhabitants. Therefore, Jacoba’s unlikely admixture of multiple, disparate kin systems—when combined with that of other Indigenous Mormons[61] and Indigenous former Mormons[62]—might have the power to confound the tyrannical aspects of Anglo Mormon temple work. It might even have the power to symbolically deactivate that work as a weapon of colonization. If Jacoba’s manipulation of kin systems can bring Anglo kinship into focus as a cultural construct rather than as a biological fact, perhaps Anglo colonization’s co-optation of kinship can be pinpointed as one of the ignition keys for the official Church’s apparatus designed to marginalize non-nuclear families. Once pinpointed, perhaps it can be used to shut down that apparatus so that the non-nuclear, conglomerative familia—the kinship form that is currently predominant across the globe and that, ironically, was originally predominant in the Anglo Mormon Church—is restored as Mormonism’s core rather than its periphery. More importantly, coated in pacha familia’s substances of blood, food, drink, tiny papers, and other instantiations of Peruvian Mormon creativity, perhaps a future world wherein all kinds of collectivities get to count as forever families can be diagrammed onto papelitos and, from there, made real.

Note: The Dialogue Foundation provides the web format of this article as a courtesy. There may be unintentional differences from the printed version. For citational and bibliographical purposes, please use the printed version or the PDFs provided online and on JSTOR.

[1] This and all other study participant names are pseudonyms unless otherwise noted.

[2] Throughout this article, the term “Mormon” is used to refer to people and things connected to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints even though the top leaders of that church have largely eschewed that term within their official dogma. I continue to use “Mormon” because none of my study participants adhered to all aspects of the official dogma of their church, yet most of them still counted themselves members of it. For example, many of my study participants, both Anglo and Peruvian, continued to identify as “Mormons” even after their church’s 2018 injunction against that moniker. In other words, my continuing usage of the identity category “Mormon” honors the social fact that the relatedness that my study participants felt toward each other as Mormons remained beyond the control of any of the many organizations that adhere to the Book of Mormon.

[3] “Anglo” was the polite term that my Peruvian Mormon study participants used to refer to North American white people. A less polite term was “gringo.”

[4] A pseudonym for a lakeside city in northern Utah.

[5] Erica Vogel, Migrant Conversions: Transforming Connections Between Peru and South Korea (Oakland: University of California Press, 2020).

[6] Arcia Tecun, “Pedro and Pita Built Peter Priesthood’s Mansion and Now They Work the Grounds: Whose Masc Does ‘the Lamanite’ Wear?,” Mormon Studies Review 9 (2022): 1–14.

[7] Brittany Romanello, “Multiculturalism as Resistance: Latina Migrants Navigate US Mormon Spaces,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 53, no. 1 (2020): 5–31.

[8] Ignacio M. García, “A Barrio Perspective on Building Zion in the Twenty-First Century,” in A Book of Mormons: Latter-Day Saints on a Modern-Day Zion, edited by Emily W. Jensen and Tracy McKay-Lamb (Ashland, Ore.: White Cloud Press, 2015), 69–75.

[9] Ulla D. Berg, Mobile Selves: Race, Migration, and Belonging in Peru and the U.S. (New York: NYU Press, 2015).

[10] Sujey Vega, “Mujerista Theology,” in The Routledge Handbook of Mormonism and Gender, edited by Amy Hoyt and Taylor G. Petrey (New York: Routledge, 2020), 598–607.

[11] Jason Palmer, “La Familia versus The Family: Matriarchal Patriarchies in Peruvian Mormonism,” Journal of the Mormon Social Science Association 1, no. 1 (2022): 123–51.

[12] Armand L. Mauss, The Angel and the Beehive: The Mormon Struggle with Assimilation (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994).

[13] David M. Schneider, “What Is Kinship All About?,” in Kinship Studies in the Morgan Centennial Year, edited by Priscilla Reining (Washington, DC: Anthropological Society of Washington, 1972), 48.

[14] Rosalynde Welch, “Theology of the Family,” in The Routledge Handbook of Mormonism and Gender, edited by Amy Hoyt and Taylor G. Petrey (New York: Routledge, 2020), 497.

[15] Not a pseudonym.

[16] Jane McBride, “Finally a Forever Family,” Liahona 47, no. 7 (June 2018): 69, available at https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/liahona/2018/07/children/finally-a-forever-family?lang=eng.

[17] Madeline Y. Hsu and Ellen D. Wu, “‘Smoke and Mirrors’: Conditional Inclusion, Model Minorities, and the Pre-1965 Dismantling of Asian Exclusion,” Journal of American Ethnic History 34, no. 4 (2015): 43–65.

[18] Hsu and Wu, “Smoke and Mirrors,” 47.

[19] Hsu and Wu, “Smoke and Mirrors,” 46.

[20] Hsu and Wu, “Smoke and Mirrors,” 47.

[21] Fenella Cannell, “Introduction: The Anthropology of Christianity,” in The Anthropology of Christianity, edited by Fenella Cannell (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2006), 1–50.

[22] H. J. François Dengah II, Elizabeth Bingham Thomas, Erica Hawvermale, and Essa Temple, “‘Find That Balance’: The Impact of Cultural Consonance and Dissonance on Mental Health among Utah and Mormon Women,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 33, no. 3 (2019): 439–58.

[23] Catherine Allen, “Ushnus and Interiority,” in Inca Sacred Space: Landscape, Site and Symbol in the Andes, edited by Frank Meddens, Katie Willis, Colin McEwan, and Nicholas Branch (London: Archetype Publications, 2014), 71–77.

[24] Joanne Rappaport and Tom Cummins, Beyond the Lettered City: Indigenous Literacies in the Andes (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2011).

[25] Rebecca Earle, The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492–1700 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014).

[26] Melissa Wei-Tsing Inouye, “Woman and Religious Organization: A ‘Microbiological’ Approach to Influence,” in The Routledge Handbook of Mormonism and Gender, edited by Amy Hoyt and Taylor G. Petrey (New York: Routledge, 2020), 305–20.

[27] Guillaume Aubert, “Kinship, Blood, and the Emergence of the Racial Nation in the French Atlantic World, 1600–1789,” in Blood and Kinship: Matter for Metaphor from Ancient Rome to the Present, edited by Christopher H. Johnson, Bernhard Jussen, David Warren Sabean, and Simon Teuscher (New York: Berghahn Books, 2013), 175–95.

[28] Peggy Levitt, God Needs No Passport: Immigrants and the Changing American Religious Landscape (New York: The New Press, 2009).

[29] Susan Bibler Coutin, “Suspension of Deportation Hearings and Measures of ‘Americanness,’” Journal of Latin American Anthropology 8, no. 2 (2003): 58–94.

[30] Tecun, “Pedro and Pita,” 13.

[31] A temple recommend is a wallet-sized card that certifies its holder’s worthiness to enter the temple. Temple entry is not allowed without a temple recommend.

[32] Temple worthiness involves an interviewee’s ability to successfully answer a dozen pat questions regarding faithfulness to Mormonism’s core notions.

[33] Natalia Sarkisian and Naomi Gerstel, Nuclear Family Values, Extended Family Lives: The Power of Race, Class, and Gender (New York: Routledge, 2012).

[34] Eyal Weizman, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation (New York: Verso, 2012).

[35] Eduardo Bonilla-Silva and Tukufu Zuberi, “Toward a Definition of White Logic and White Methods,” in White Logic, White Methods: Racism and Methodology, edited by Tukufu Zuberi and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008), 3–27.

[36] Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1977).

[37] Elizabeth F. S. Roberts, “Assisted Existence: An Ethnography of Being in Ecuador,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19, no. 3 (2013): 562–80.

[38] Bruno Latour, Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988).

[39] Janan Graham-Russell, “A Balm in Gilead: Reconciling Black Bodies within a Mormon Imagination,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 51, no. 3 (Fall 2018): 185–92.

[40] Marilyn Strathern, After Nature: English Kinship in the Late Twentieth Century (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 53.