Articles/Essays – Volume 58, No. 1

Unveiling the Invisible Hand of Providence: Examining the Smith Family’s Economic and Spiritual Catalysts Amid Troubling Times and the Panic of 1819

Desperation is the raw material of drastic change. Only those who can leave behind everything they have ever believed in can hope to escape.

—William S. Burroughs (1914–1997)[1]

Joseph Smith ascended to the revered position of prophet, eventually capturing the allegiance of millions. However, the precise chain of events that led him to that position is shrouded in uncertainty, given the formidable challenge of interpreting early Mormon history before his ascent to prominence. Originating from humble beginnings as an unknown farm boy, Joseph’s[2] journey is further obscured by the family’s nomadic lifestyle, particularly before their relocation to New York. Their transient nature poses a barrier to unraveling the intricacies of the family’s character and motivations. Compounding the challenge is the scarcity of contemporaneous documentation, leaving the realities of Joseph’s early life prone to speculation. Existing accounts detailing his transformation into a prophet and seer are marred by biases of related parties who could have motives for his success, or detractors with motives to impede his actions. While these sources offer a thread of reality, reconstructing the overall context the thread was weaved into provides insight into the shaping of the events in the Smiths’ lives.

Numerous scholars have extensively delved into the early life of Joseph Smith. In works such as Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling by Richard Bushman, No Man Knows My History by Fawn Brodie, and Joseph Smith: The Making of a Prophet by Dan Vogel, the intricate details of Joseph’s early life are illuminated. Paradigm-shifting scholarship about the Smith family’s supernatural beliefs come from works such as Early Mormonism and the Magic Worldview by D. Michael Quinn and Mark Ashurst-McGee’s graduate thesis, “A Pathway to Prophethood: Joseph Smith Junior as Rodsman, Village Seer, and Judeo-Christian Prophet.” In addition, Adam Jortner’s work, including his book Blood from the Sky: Miracles and Politics in the Early American Republic, further sets the stage for contextualizing the early American supernatural environment. This essay builds upon this groundbreaking scholarship, focusing on the apocalyptic events (e.g., earthquakes and comets) and economic circumstances that provide essential context for the formation of the Smiths’ beliefs and circumstances.

This essay explores the impact of apocalyptic fears and economic challenges between 1809 and 1822 on the Smith family, particularly Joseph Smith Jr. It argues that turmoil, tragedy, and portents of doom during Joseph’s upbringing shaped the family’s choice of occupations and contributed to the development of their core beliefs in divination, astrology, and magical practices, particularly during the Panic of 1819, the nation’s first depression, which lingered until the mid-1820s.

This essay relies heavily on contemporaneous newspaper accounts, which will be both beneficial and detrimental to an analysis of the environmental context. Several challenges come with relying primarily on contemporaneous newspaper articles for context including assumptions about information awareness, selection bias, and a tendency toward sensationalism. To attempt to minimize the problems of information awareness, the research prioritized newspapers that were local to the Smiths. Selection bias may be present because articles in newspapers were typically written by the more educated or literate, causing the true experiences and beliefs of poor, uneducated, or illiterate people to be underrepresented or ridiculed. In addition, due to the media’s attraction to sensationalism, issues presented may or may not have been as important to the average citizen as portrayed.

In addition, the passage of time, the progression of knowledge, and the profound cultural shifts over the last two centuries have created significant barriers for people at present to fully empathize with the mental frameworks, worldviews, and daily challenges faced by people of that era. Due to these challenges, this essay will employ a significant amount of qualifying language. However, despite these limitations and challenges, the study will provide insights into factors that would have had a high likelihood of influencing the Smith family along with many others during the period of study.

Life for people in the early 1800s was vastly different from ours. They lacked many of the scientific discoveries that we rely on every day to form our worldview. Although the Enlightenment had dissuaded many from adhering to superstitious beliefs, many still held to this hidden “knowledge” of ancient people. They lived in a time when disease was caused by bad air, charms and amulets were sometimes used to ward off disease, and astronomical events were seen by many to be highly significant to their lives. Lacking the scientific knowledge of today, many people still believed that the sun, moon, stars, planets, and even comets were inhabited,[3] and economic hardships were often seen as signs of God’s disfavor.

It was within this environment that Joseph Smith Sr. and Lucy Mack Smith started their family. After experiencing a reasonably comfortable lifestyle while living near his extended family, Joseph Smith Sr. experienced great misfortune, losing everything in a failed ginseng venture in 1803.[4] From this time forward, the family traveled from place to place, struggling to get ahead and regain what they had lost, their extended families seemingly unable or unwilling to help. Their loss seems to have also imposed some level of economic suffering on their entire extended families.[5]

In Vermont, because state law required towns to provide for the welfare their poor, many towns “warned out” undesirable newcomers to avoid the responsibility of supporting them. Joseph Smith Sr. received such a notice on December 1, 1809, while living in Royalton, Vermont, which was adjacent to his previous home in Tunbridge.[6] Nevertheless, the family remained there until at least 1811 through Lucy’s pregnancy and loss of their son Ephraim, who died at birth, and the birth of another son, William.

Joseph Smith Jr., age five, would begin growing up in a rapidly changing and contentious world. The religious landscape during this time was undergoing a remarkable shift. Between the ratification of the US Constitution and the passage of disestablishment bills between 1800 and 1830, a gradual erosion of the power of taxation wielded by churches occurred as church and state began their gradual separation. This shift forced ministers to increasingly rely on voluntary contributions from adherents rather than support through taxation. A competitive atmosphere emerged, not only among different denominations but also between established congregationalist churches and traveling itinerant preachers. These ministers, now dependent on attracting converts for their survival rather than being supported by the towns with the church at the center, found themselves in competition not only for followers but also for financial resources and property. This contest for both opinions and resources often led to tensions and animosity within the religious communities.[7]

The increase in conflicting opinions troubled many. Amanda Porterfield in her book Conceived in Doubt: Religion and Politics in the New American Nation argues that “churches manipulated distrust as well as relieved it, feeding the uncertainty and instability they worked to resolve.”[8] One itinerant preacher from Vermont met a man who noted that “he wished to have Religion, if he knew which way was right, but there were so many.”[9] Lucy Smith had previously struggled with finding religion, saying after one meeting with the Presbyterians in around 1802 that “I returned saying in my heart there is not on Earth the religion which I seek.”[10] Around 1811 Joseph Smith Sr.’s mind also “became much excited upon the subject of religion.” Critics in Vermont claimed that Joseph Sr. had leanings toward the deist writings of Voltaire and Thomas Paine,[11] who were highly critical of sectarian priests and organized religion in general, Paine insisting that the “doctrines of damnation and salvation . . . had been contrived by priests who manipulated fear in the service of political tyrants.”[12] Joseph Sr. belonged to no church but, according to Lucy, “contended for the ancient order” as established by Christ and his apostles. While contemplating “the confusion and discord that reigned in the religious world,” he experienced a dreary and ominous dream.

Lucy recounted how her husband found himself in a barren field, surrounded by nothing but dead fallen timber, which his guide indicated represented “the world which now lieth inanimate and dumb, in regard to the true religion.” His guide told him to travel on until he found a box that held fruit that would give him wisdom and understanding. Upon opening the box and starting to eat, he recounted, “all manner of beasts, horned cattle, and roaring animals rose up on every side in the most threatening manner possible, tearing the earth, tossing their horns, and bellowing most terrifically all around me. They finally came so close upon me that I was compelled to drop the box and fly for my life.”[13]

Being an individual who interpreted dreams, Lucy may have interpreted this dream with guidance published in one of the many works similar to Ibrahim Ali Mahomed Hafez’s The Oneirocritic: Being a Treatise on the Art of Foretelling Future Events, by Dreams, Moles, Cards, the Signs of the Zodiac and the Planets, which contains interpretations of numerous elements found in Joseph Sr.’s dreams. According to this work, dreaming of being pursued by a bull denotes “that many injurious reports will be spread of your character, and that you will be in danger of losing your friends.” Similarly, dreaming of a dog barking and snarling suggests that “enemies are secretly endeavoring to destroy your reputation and happiness.”[14] From this point forward, Joseph Sr. became even more convinced that no true church existed on Earth.[15] This dream portending poverty and aspersion reflected themes that had already occurred and would persist throughout the family’s life, resembling the feelings and experiences his son Joseph Jr. would describe in the following decades.

That year they would move to Lebanon, New Hampshire. It would be a year of great foreboding. On June 12, 1811, a comet began to be visible in the western sky, starting very nebulously but coming more into view in the fall.[16] This comet would come to have the longest recorded period of visibility of any comet until the appearance of the Comet Hale–Bopp in 1997 and would, at its greatest visibility, have a coma larger than the sun.[17] Many believed the appearance of a comet was an omen to be feared. The minds of some people began to remember all the calamities through the ages that had occurred as a result of the appearance of comets. Some were alarmed, fearing it was “the harbinger of War.”[18]

An unrelenting stream of terrifying events would begin to unfold, which likely deeply impacted Joseph as he transitioned from the age of five when the comet first appeared in 1811 to the year 1818 when he turned twelve.

Despite some skeptics dismissing the historical precedents set by comets as mere superstition, all the world was talking about it, recounting the earthquakes, pestilence, and wars they portended.[19] Joseph and his family would soon encounter compelling evidence linking this celestial event to struggles in their own lives. In October 1811, alongside reports about the comet,[20] newspapers noted that “in almost every democratic paper will be seen several columns filled with blustering and threatening of war with England.”[21]

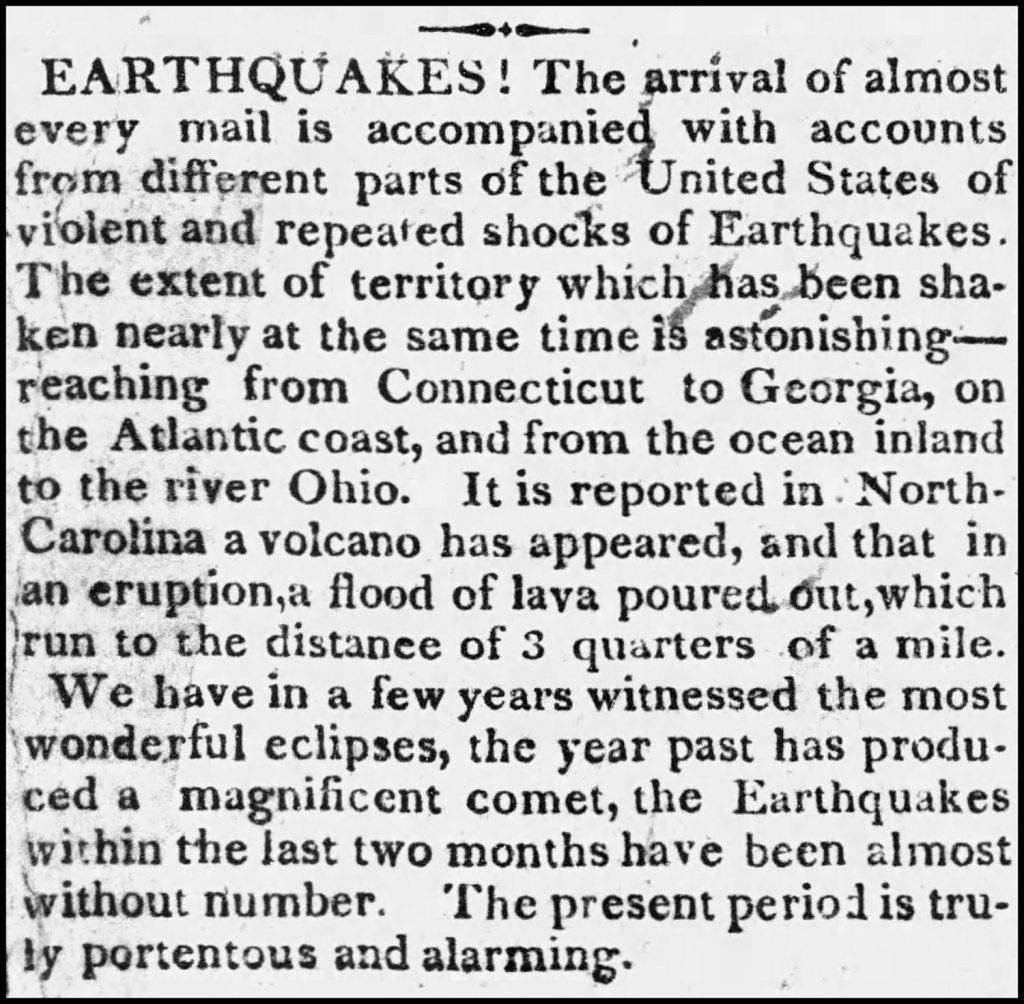

In December 1811, a catastrophic series of earthquakes centered in New Madrid, Missouri began, which caused widespread fear and upheaval. The earthquakes were felt as far as Massachusetts, Louisiana, and possibly even Vermont.[22] They destroyed half of New Madrid and caused damage and changes to the landscape within six hundred thousand square kilometers of its epicenter. With over three thousand distinct seismic shocks at estimated magnitudes of up to 7.7 over a period of five months, it is thought to be “largest outburst of seismic energy in American history.” It not only destroyed half of New Madrid but also created new lakes, temporarily reversed the course of the Mississippi River, and caused deep seismic cracks, sulfuric vapors,[23] and large areas of “sunk country.”[24] These earthquakes were rumored to have been prophesied by the Native American prophet Tenskwatawa through his brother Tecumseh,[25] and Indigenous legend suggested that there had been prior widespread upheaval in this area.[26] As the ominous comet dimly peered at Earth’s inhabitants, “a dreary darkness brooded over the whole face of the creation.”[27]

Figure 1: Buffalo Gazette, Mar. 11, 1812, [3].

“A great many superstitious people” of Raleigh, North Carolina were alarmed not only by the comet but also by the bloodlike color of the sun, the aurora borealis, and a significant earthquake they experienced in December. It brought to mind all the appearances “that are still believed . . . to have been the awful precursors” of the Revolutionary War.[28]

Susanne Leikam, a scholar who has written on disaster studies, noted that the backdrop of the Second Great Awakening along with a solar eclipse in November 1811, the changes in the landscape, and “the repeated shakings of the earth—some of them occurring during the actual open-air camp meetings—were interpreted as demonstrations of God’s power, as calls to repentance, and also as warnings to return to a pious lifestyle.”[29]

Less than six months after the comet’s appearance, its anticipated effects reverberated throughout the world. The War of 1812 commenced with Great Britain on June 18, 1812, and immediately afterward, Napoleon invaded Russia on June 24, 1812. This period brought anxiety to Vermont and New Hampshire, where concerns of a possible British invasion prevailed. In response, twenty-eight men from Lebanon joined a militia to safeguard against potential attacks.[30] In Buffalo, some individuals, driven by their superstitions and concerns about the war, voiced an old adage: “What the sword spares, the pestilence will destroy, and what pestilence spares will be overwhelmed by famine.”[31]

Amid this turmoil and the ominous signs of impending doom, the years 1812 and 1813 brought typhoid fever to Lebanon.[32] One by one, each child in the Smith family fell ill. After the doctor declared their ten-year-old daughter Sophronia was too far gone for his help, seven-year-old Joseph witnessed his parents’ faith as they knelt by her bedside supplicating for God to answer their prayers. After Sophronia apparently stopped breathing, Lucy held Sophronia’s lifeless body despondently while pacing the floor, believing that God would heal her. And Sophronia miraculously returned to life.[33]

Following Joseph Jr.’s recovery from this pestilence, he endured excruciating pain for two weeks due to infection resulting from typhoid fever, leading to the horrifying and traumatizing experience of having some of his leg bone cut out without any anesthesia as his father held him down. This ordeal left him either bedridden or relying on crutches from age seven to ten.[34] The British blockade followed by the Embargo Act of 1813 compounded their suffering. Cost of living increased 20 percent in 1813 alone, plus another 10 percent in 1814.[35]

In 1814, a year marked by the burning of the US Capitol by the British on August 24th, the Smiths faced crop failures, which continued through 1815. As they entered the spring of 1816, the Smiths received yet another “warning out” notice from local town supervisors in March.[36] This warning out was likely a devastating blow to the Smiths, happening during a time that must have, for them, felt like the end of the world. In spite of their hardships, the Smiths attempted to plant crops once more. But 1816, a year dubbed by some farmers as “eighteen hundred and starve to death,”[37] posed an insurmountable challenge. The eruption of Indonesia’s Mount Tambora in April 1815 had unleashed global climatic disruptions that went on to haunt them in the following year. A seaman near the eruption vividly recounted, “The darkness was so profound during the remainder of the day, that I never saw any thing equal to it in the darkest night—it was impossible to see your hand when held up close to your eyes.”[38] Reports would eventually reach the United States a year later, describing a calamitous scene at the epicenter: a volcano-induced whirlwind that flattened a village, uprooted trees, and lifted cattle and people into the air.[39]

Figure 2: Claude-Louis Desrais, Caricature sur la comète de 1811 [Caricature on the comet of 1811], National Library of France.

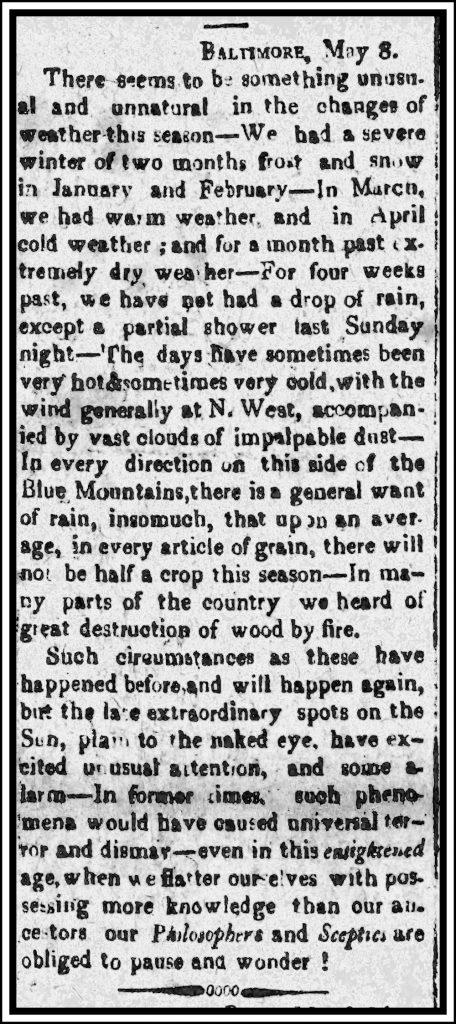

Although Americans didn’t understand the cause of the 1816 weather anomalies, they experienced droughts, severe freezes every month of the year, dry fog, birds dropping dead in the streets, vast clouds of impalpable dust, and widespread crop failures.[40] In Italy they “received a greater quantity of snow than has been known in the memory of man.” And to make it more alarming, the falling snow was red and yellow. The Italians formed “religious processions to appease the heavens.”[41]

Reports of these extreme weather events around the world caused continued anxieties and contemplation of apocalyptic happenings. In the midst of this, Joseph Smith Sr., desperate for food and employment and limited in means, left his family behind and set out toward Palmyra, New York, a place where he had heard “the farmers raised wheat in abundance.”[42]

In the winter of 1816, after difficulties reconciling accounts with creditors, Lucy and the rest of the family left for Palmyra to join their husband and father. The hopelessness of a callous world would manifest itself in the man who transported them to Palmyra, Mr. Howard. Lucy said he was “an unprincipled unfeeling wretch by the manner in which he handled my goods & money as well as his treatment to my children, especially Joseph who was still somewhat lame” and often forced to travel for miles on foot. Finally, they arrived in Palmyra penniless.[43] Lucy Smith remembered that they “were much reduced—not from indolence, but on account of many reverses of fortune, with which our lives had been rather singularly marked.”[44]

When the Smith family arrived in New York, they did not find significantly better conditions. Lucy later recalled their plan to escape their poverty:

We <all> now Sat down and maturely councilled togather as to what course it was best to take how we shold proceed to buisness in our then destitute circumstances It was agreed by each one of us that it was <most> advisable to aply all our energies together and endeavor to obtain a Piece of land as this was then a new country and land was low being in its rude state but it was almost a time of famine wheat was $2.50 per bushel and other things in proportion how shall we said My Husband be able to sustain ourselves and have anything left to buy land.[45]

Figure 3: Vermont Republican and American Journal. Windham, Windsor and Orange County Advertiser, May 20, 1816, [3], newspapers.com.

Historical records verify Lucy’s recollection about prices. Average wholesale wheat prices had increased from $1.50 per bushel in 1815 to $2.41 per bushel in 1817 due to the preceding year’s unprecedented weather and failed crops.[46] This period of food shortage must have been traumatic for young William Smith, age six at the time, to have been able to remember fifty-eight years later: “It is Still in my memorey provisions very high corn at one dollar fifty cts per bushel, wheat 3 dollars and not much to be at that price.”[47]

In April of 1817, the Native Americans in Buffalo comprising the Senecas, Cayugas, and Onondagas, were suffering a dire food shortage due to the winter’s devastating impact on their corn crops. The Presbyterian Synod at Geneva, which oversaw Palmyra,[48] made resolutions to encourage their congregants and fellow Christians to provide aid to the Native Americans. The aid was intended to be distributed “in such a manner as shall have the best tendency to encourage the industry of the Indians, by taking in exchange for provisions, baskets, brooms, and such other articles as Indians are in the habit of manufacturing.”[49]

The synod passionately implored their members to extend assistance, emphasizing the urgency of the situation:

If these resolutions are carried into effect the natives may be supplied with bread; if not they must starve. —Mere resolutions will never feed them. Their fate remains yet to be decided. If ministers and christians generally, refuse or delay to help them, they die. . . . In various ways they have sought relief but could not obtain it. . . . They have come even to the door of the sanctuary to see if Christians have any bowels of compassion, or are capable of feeling for their fellow creatures. . . . Were the blessed Jesus on earth, as he once was; and could they go to him and tell their distress, his tender heart would melt with compassion. He would wipe the falling tear from their cheeks; he would feed their little children, now starving in the arms of their distressed mothers : never was one denied who applied to him for relief . . . by doing good to these heathen, you may unlock the prison of Satan and deliver nations of captive souls from the thraldom of sin. Give then, O give freely: give prayerfully, and let the Indians see what christians can do.[50]

The measure was supported by a “benevolent few,” who hoped their benevolence would bring Christianity into a new light. But the measure was unpopular.[51] The relationship between Natives and Christian settlers was fraught with enmity. For some Christians, Native Americans were simply seen as heathen barbarians ruled by superstition.[52] But some Christians who understood Indigenous culture saw a possibility that Native Americans were fallen Israelites, some theorizing they were the biblical Danites who were prophesied to be “a serpent by the way, an adder in the path, that biteth the horse heels, so that his rider shall fall backward.”[53]

The alliances of many tribes with Tecumseh and the Native American prophet Tenskwatawa along with their craftiness, cunning, strategem, and brutality in burning villages and killing colonizers caused great distrust. Some would have believed these “heathens” were receiving the just punishments of God. “Mercenary speculators [give] them dinners, get them drunk, make them presents, stroke their heads and tell them how they loved them.” Distrust caused the Natives to wonder whether the missionaries and schoolmasters had come to “do good or to fleece them.”[54] At the same time, Enlightenment philosophies, which influenced many Deists’ and Christians’ beliefs that the revolution’s success was part of God’s divine purpose, also convinced them that the misery of Native Americans (and slaves) was “God’s will and plan.”[55]

A few days after the donations were made to the Natives in Buffalo, the Ontario Repository in Canandaigua and the Geneva Gazette reported that a “severe earthquake had sunk a country ninety miles in extent” in the narrow neck of land in current-day Mexico called the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.[56] “The whole face of the country had been turned up, and the rivers Tobasco [now Grijalva] and St. Francis were rendered impassable by the thousand floating trees on the surface,” the newspaper reported. “An Indian village had been swallowed up, with all its inhabitants.”[57]

These events made a long-term impression. Joseph later recalled, “from the age of twelve years to fifteen I pondered many things in my heart concerning the situation of the world of mankind—the contentions and divisions, the wickedness and abominations, and the darkness which pervaded the minds of mankind.”[58]

When the 1818 growing season arrived, Joseph Sr. and Alvin Smith likely remembered the record-high grain prices and food shortages of the previous year and perhaps sought ways to produce less expensive ingredients for their cake and beer shop and ensure their future survival throughout the coming year. If they were not paying attention to economic conditions, they might not have realized that grain prices had fallen about 20–25 percent between the spring of 1817 and the spring of 1818.[59]

Seeking a means of survival, Joseph Sr. and Alvin entered into some sort of partnership with Jeremiah Hurlbut, a local farmer, to farm the land of his widowed mother Hannah.[60] They also purchased two horses from Hurlbut, signing a promissory note on March 27, 1818 stating they would “Pay to Jeremiah Hurlbut Or Barer the sum Of Sixty five Dollars to be Paid in good Merchant Grain at the market Price by the first Ganuary.”[61]

By August 1818, the crops they were growing had matured and were probably ready to harvest. But for whatever reason, the Smiths didn’t harvest all the crops.[62] Something had gone wrong between the Smiths and Hurlbut. In February 1819, a month after the debt was due to Hurlbut, Joseph Sr. and Alvin sued him for $146.50, which included $80.00 for fraud for selling them defective horses, $25.00 for breach of contract, and $41.50 for services rendered by Joseph and his sons, as well as other items.[63]

Hurlbut counterclaimed that the Smiths owed him offsets for $25 for “damages for not working the land according to agreement” and “28 dollars damage sustaned in the wrong apprisal of crops.” Hurlbut also sought reimbursement for half of the costs of his labor, seed, and other goods related to the farming of the land totaling $23.81.[64] The jury awarded Joseph and Alvin a judgment against Hurlbut of $45.54, which may have represented the $41.50 for services rendered plus interest and court costs. Unfortunately, extant documents do not detail how the judgment reconciles with the claims and counterclaims.[65]

Understanding the probable reasons for the conflict and its impact on the Smith family requires considering the economic environment in which it took place. Between March 1818 when they signed the promissory note and January 1819 when they were required to pay Hurlbut, several economic factors combined to create a credit crisis that led to a sharp decline in commodity and land prices, causing widespread unemployment in the cities and widespread debt defaults, now known as the Panic of 1819. The US economic expansion was fueled by unregulated banking, rampant land speculation, and export of specie (money in coin) due to rising imports. The panic was precipitated by the contractionary policies of the Bank of the United States in mid-1818.[66]

Economist Murray Rothbard explained the harsh economic conditions of the time:

The severe contraction of the money supply, added to an increased demand for liquidity, led to a rapid and very heavy drop in prices. Most important for the American economy were the prices of the great export staples, and their fall was remarkably precipitate. The index of export staples fell from 169 in August, 1818, and 158 in November, 1818, to 77 in June, 1819. . . . In Massachusetts, the wages of agricultural workers fluctuated sharply with the boom and contraction, averaging sixty cents per day in 1811, $1.50 in 1818, and fifty-three cents in 1819. . . . Unskilled turnpike workers paid seventy-five cents a day in early 1818 received only twelve cents a day in 1819.

Economic distress was suffered by all groups in the community. The great fall in prices heavily increased the burden of fixed money debts, and provided a great impetus toward debtor insolvency. The distress of the farmers, occasioned by the fall in agricultural and real estate prices, was aggravated by the mass of private and bank debts that they had contracted during the boom period.[67]

The fixed dollar amount of Joseph and Alvin’s liability to Hurlbut, which was to be valued at the time of delivery, resulted in Joseph Sr. and Alvin to need to deliver significantly more grain than originally expected when they signed the note. From the summer of 1817 to the summer of 1819, New York wheat prices plummeted 43 percent and finally hit their low point in 1821 at around eighty-eight cents per bushel, about 63 percent below the 1817 peak.[68] The fifty-three dollars of “crops on the ground”[69] showing as partially cancelling the promissory note had likely been valued before Hurlbut had discovered the reality of drastically lower crop values. This sudden decrease would explain Hurlbut’s later claim for a “wrong apprisal of crops.”[70]

The Smiths may have become aware of the sudden price decline through Hurlbut’s protests and tried to avoid being held to the contract by suing Hurlbut. At a time when unemployment was rising, wages were suddenly extremely low, and there was a great shortage of money, producing cash or valuable trade goods would be exceedingly difficult. The sixty-five-dollar liability would have normally been equivalent to several months of labor but would take substantially more time and effort to earn due to the collapse of wages.

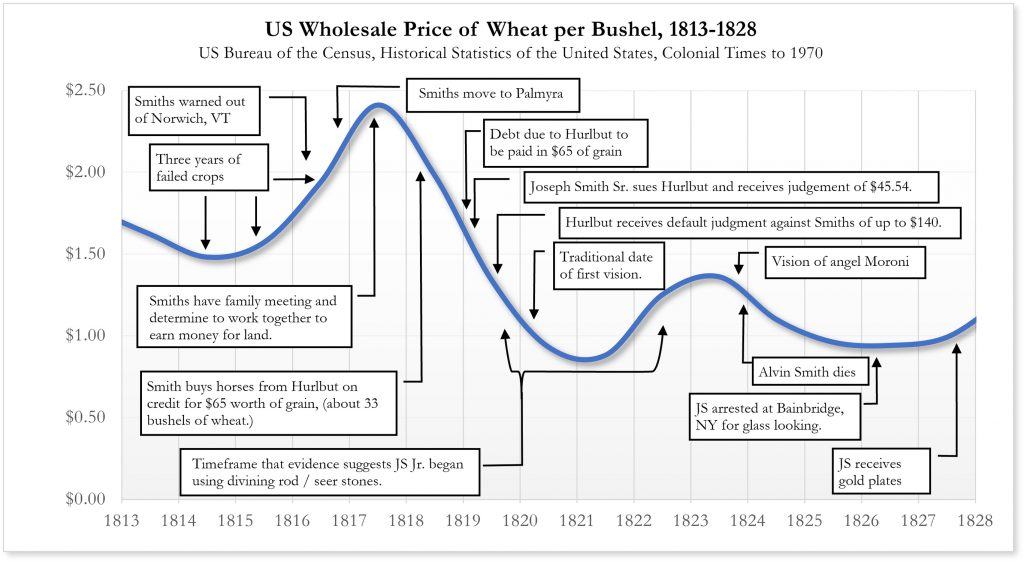

The prices of wheat from 1813 to 1828 shown in figure 4 can serve as a proxy for the severity of the depression illustrated alongside events in the Smiths’ lives.

Figure 4: US wholesale wheat prices overlaid with a timeline of events in the Smith family’s lives.

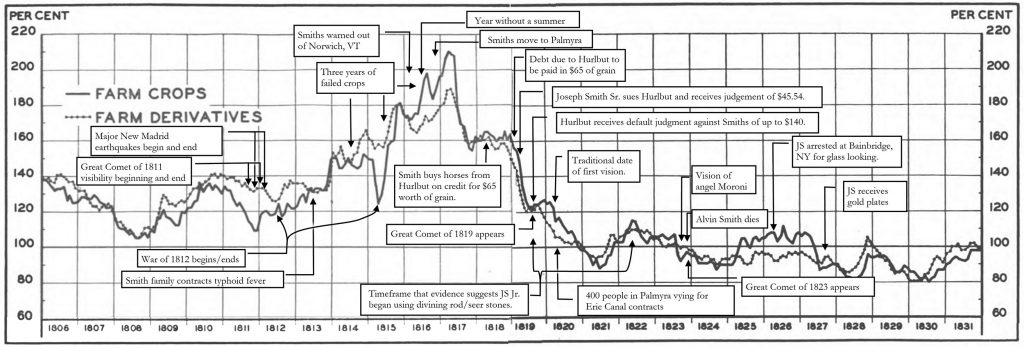

The chart in figure 5 shows the same events with more granular data derived from a study performed in 1936 specifically for Philadelphia crop prices between 1806 and 1831.[71] This data illustrates the dramatic price changes and gives context to the events occurring in the Smith family’s environment.

Figure 5: Philadelphia crop and crop derivative prices overlaid with a timeline of events in the Smith family’s lives.

Hurlbut did not give up despite the judgment against him. The day after the judgment, on June 26, 1819, Hurlbut appealed and sued Joseph Sr. and Alvin for $140. He claimed Joseph and Alvin were required to pay the $65 “according to the tenor and effect of the said note” and that, although requested, they had “not paid said note or any part thereof to the said Plaintiff nor have otherwise paid and satisfied to the said Plaintiff the said sum of money or any part thereof, but they to do the same have hitherto wholly refused, and still do refuse.”[72]

Available documents provide some clues but are inconclusive about the precise reason for the appeal. The promissory note was partially cancelled with writing on the back saying “Paid on the within note fifty three dollars by the crops on the ground August 10, 1818,” contradicting Hurlbut’s claim that the Smiths had paid nothing.[73] But the agreement was not for the Smiths to pay $65 worth of crops on the ground, but rather for $65 “to be paid in good merchantable grain at the market price.” Crops on the ground would not have been considered “merchantable grain.” The real issue of the appeal was likely whether Hurlbut’s note had been paid at all. Under contract law, Hurlbut could demand payment according to the terms of the note, and not with a valuable substitution.[74]

One of the primary reasons the Smiths moved to New York was to be able to grow wheat in abundance, but economic conditions of the time thwarted their plans. The Smiths did not have any horses or land, and renting a farm would not generate enough profit to support their large family’s needs. Moreover, it is unlikely that anyone in the area would want to partner with them so soon after they sued their former partner. The nation’s first depression was taking hold. “The pressure for money and the stagnation of business [were then] the common topics of complaint from all quarters of the country,” the cry of distress was becoming universal,[75] and the Smiths’ large family was destitute. The Smiths were now under pressure to come up with a defense to Hurlbut’s countersuit from the June 26, 1819 appeal within twenty days.[76]

Figure 6: Baltimore Maryland American, June 16, 1819, University of Maryland Special Collections.

One of young Joseph’s responsibilities was picking up the local Palmyra Register newspaper for his father once a week, bringing a little wood to sell and finding an odd job to do at the store.[77] Newspapers were particularly important in helping those in the outlying areas to gain a view of the happenings in the world.

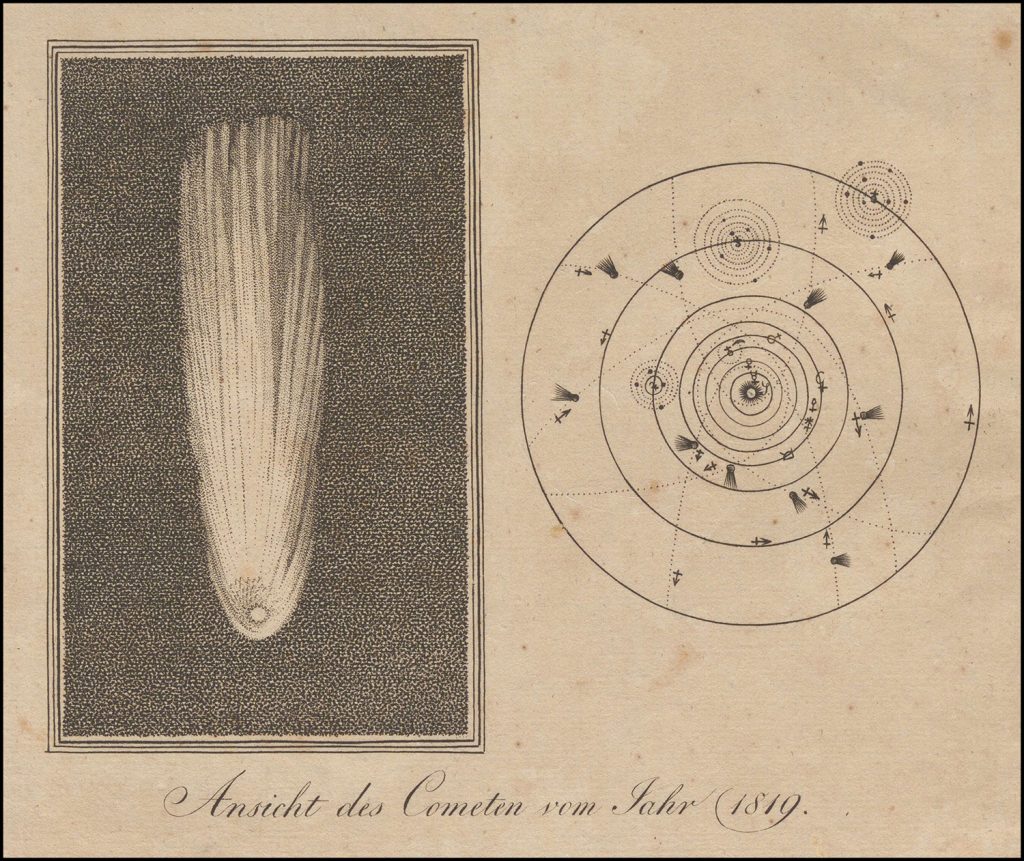

Following the sudden price shock, some perceived the troubles as signs of the end times and the “work of Providence.”[78] As the Smith family would have been contemplating the continuous hard times, the Hurlbut countersuit, commodity collapse, omens leading to war, earthquakes, pestilence, famine, and the troubles and turmoil of their lives, all perhaps portended by that celestial omen in 1811, another omen manifested. On July 7, 1819, the Palmyra Register reported that another comet had appeared that week.[79] People immediately noticed that its magnitude and brilliance resembled and even exceeded that of the Great Comet of 1811, some thinking it had returned. In addition, some noticed that its tail pointed toward the pole star.[80] These coincidences served to stir divisions among people. For some it “served in some measure to revive and countenance the obsolete doctrines of astrology,”[81] worries about another war, and recollections of old rumors that the earth would one day be burned by an incendiary comet,[82] crying “Lo, here!” and others, “Lo, there!,” attributing astronomical events to all sorts of misfortune.[83] But others hoped that its appearance and peaceful passing would correct the “erroneous and superstitious notions, which its immediate predecessor (perhaps itself,) created.”[84] This comet, now known as the Great Comet of 1819, would remain with them the rest of the summer.

The Smith family and, in fact, the entire United States would not avoid the turmoil portended by this new comet, though the effects were not what some feared. Many banks in New York suddenly stopped redeeming their banknotes for gold and silver. During July, Jefferson Bank, Bank of Troy, and Chenango Bank closed their doors. Plattsburgh Bank, Greene County Bank, and Ontario Bank refused to redeem their bills.[85] “‘Rumor with her ten thousand tongues,’ [had] simultaneously made war with all the Banks in the State, as if determined at ‘one fell swoop’ to bury the whole of them in one common ruin.”[86] These failures would cause lasting disdain of banking institutions, which many people perceived were to blame for the country’s ills.[87]

Figure 7: Unknown, Der im Sommer 1819 von der Erde mit bloßem Auge sichtbare Komet C/1819 N1 (Großer Komet, auch Komet Tralles genannt), 1819, Wien Museum Inv.-Nr. 9816, CC0, https:// sammlung.wienmuseum.at/en/object/95068/.

The Baltimore Morning Chronicle reflected the cynicism of the time:

The tail of the comet is so destitute of radiance, that some sage astronomers have conjectured that it was composed of certain bank-paper—it has a pale squalid death-like appearance of silver—as if it could never return to that glowing and golden radiance, that formerly denoted the circulating radiance of a comet; it shews the sickly lustre of death—an attempt to irradiate the heavens by the beams of expiring light—it is a just representative of some of our banks.[88]

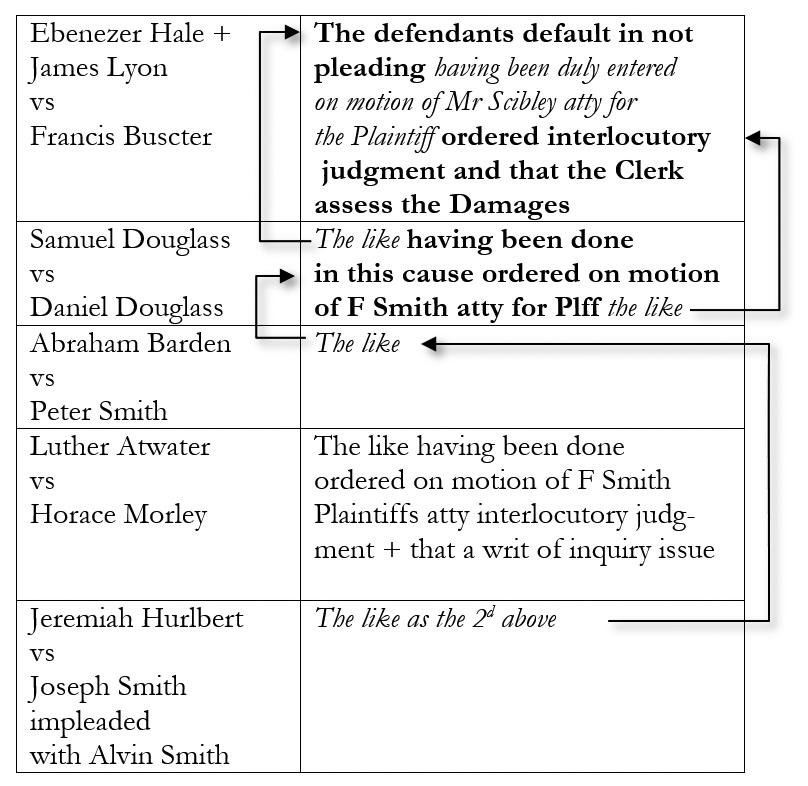

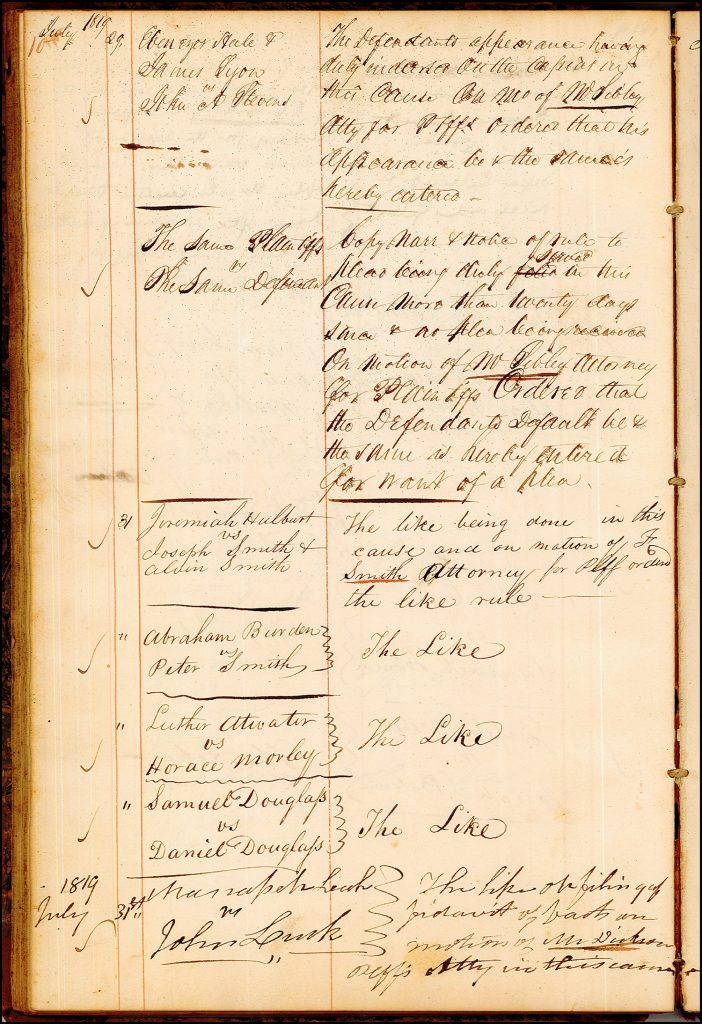

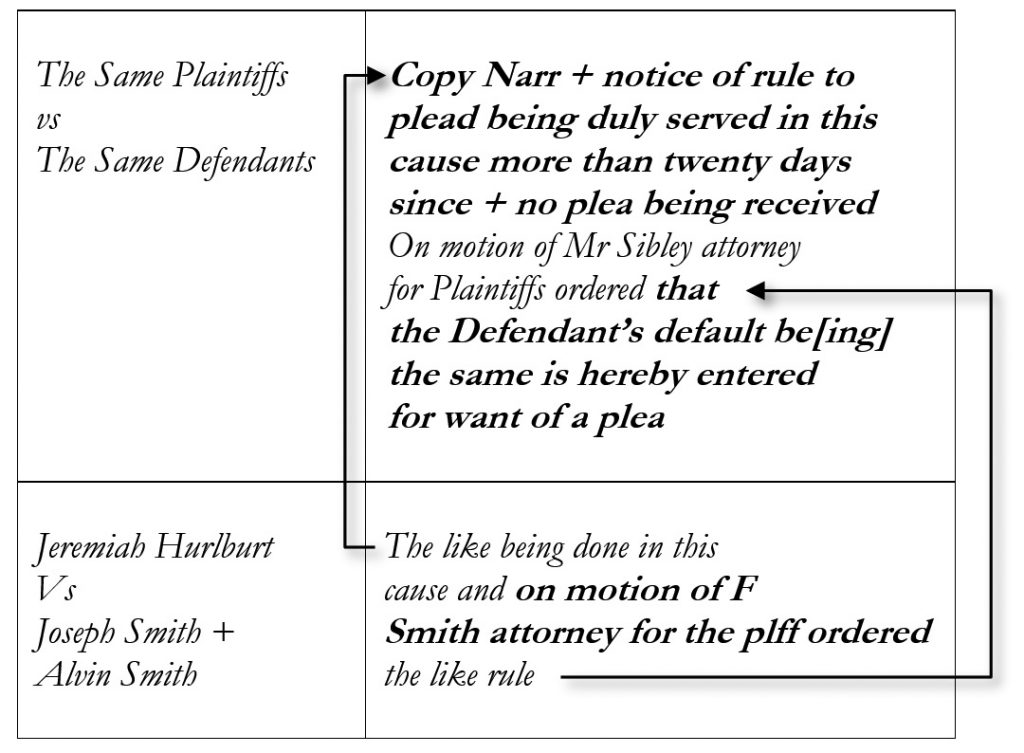

In regard to Hurlbut’s countersuit, the Joseph Smith Papers editors wrote in their historical introduction to the case that “a scribal ambiguity in the court of common pleas docket renders the outcome of the case uncertain.”[89] However, a newly discovered Canandaigua Court Common Rule Book entry, analyzed in Appendix 2, resolves the ambiguity of the transcription.

The docket entry is as follows:[90]

| Jeremiah | Copy Narr[atio] + notice of rule to plead being duly |

| Hurlburt | served in this cause more than 20 days since + No plea |

| Vs | being received On motion of F Smith attorney for plffs |

| Joseph Smith + | ordered that the defendants default be[ing] the same is |

| Alvin Smith | hereby entered for want of a plea |

The docket recorded that the Smiths didn’t offer the required defense to Hurlbut’s claim that they had not paid the note, so on July 31st, 1819 a default judgment was entered against them.

Understanding the rule book entry helps us correctly transcribe the previously ambiguous docket entry as follows:

The defendants default in not pleading having been duly entered on motion of F Smith Atty for Plaintiff ordered interlocutory judgment and that the Clerk assess the Damages.[91]

The conflict likely created tension between the Smith family, Hurlbut, and possibly other community members. Sometime between April 1819 and that winter, the Smith family, comprising eight children aged three to twenty-one, relocated approximately one and a half miles to the south, near the Palmyra–Farmington town line.[92] They had been constructing a small cabin in the woods,[93] perhaps prompted by the ongoing conflict or even related to oneirocritics’ notions that simply dreaming of a comet would be reason to relocate to a new residence.[94]

By August, the nation was experiencing devastatingly hard times. In Delaware and Maryland, newspapers reported the pressure as being “‘equal to the worst days of the embargo’. . . . We have been nationally drunk, and we are now getting sober through an interval of languor and sickly depression.”[95]

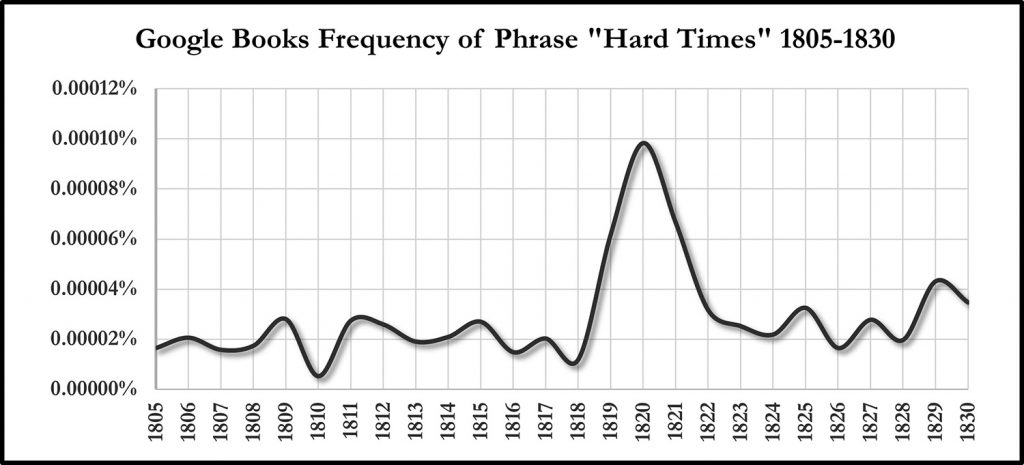

Figure 8: “Hard times” search in Google Books Ngram Viewer, 1810- 1830, 2019 American English corpus, case insensitive, no smoothing.

Orsamus Turner, who came to Palmyra as an apprentice printer in about 1819, reported that he first saw the Smith family in the winter of 1819–1820, in a “rude log house” with “a small spot underbrushed around it.”[96] The land on which the cabin was located was described as a “nearly wild or unimproved piece of land, mostly covered by standing timber,” and the Smiths were said to occupy it “by the rights of ‘squatter sovereignty.’”[97]

Local gossip that Joseph Smith Sr. had tried to sue Hurlbut for fraud may have influenced Turner’s opinion that Joseph Sr. was “a little given to difficulties with neighbors, and petty law-suits.”[98] A reputation of this type would likely have made others less willing to extend credit to the Smiths in the future, and unfortunately, as will be shown later, credit was quickly becoming the only means of paying for things.[99]

The Smith family was marginalized and living in the backwoods without farmland or horses.[100] Troubles had been constant and unrelenting in their lives, but now they were particularly destitute at exactly the wrong time. Joseph Jr. attended some school but noted that “it required the exertions of all that were able to render any assistance for the support of the Family therefore we were deprived of the bennifit of an education.”[101]

But a feeling of excitement and uncertainty was in the air. In November 1819, the Palmyra Register reported that the canal engineers would soon be in the vicinity to make contracts for the Erie Canal’s construction.[102] Low wages, driven by high unemployment, enabled companies and governments with means to complete these projects more economically.

As the depression deepened, people speculated about its cause. Many attributed it to society’s obsession with fashion and worldliness driven by speculative boom. Others believed poverty was due to idleness.[103] This bias should be considered in some of the Smiths’ neighbors’ assessments that the family was lazy and that they simply did not want to work. The lack of farming may have prompted contemplation among their neighbors about “the long New England tradition that paired improvement of the land with improvement of the soul,” suggesting to others that the Smith family might have been “failing to do God’s work either in the fields or in their own hearts.”[104]

However, farming wouldn’t have been very profitable except for subsistence. In 1820 one fairly well-to-do farmer complained that “As for wheat and other grain, my Son Penn says they ar’nt worth sowing. So here we are, every day at mealtime, snarling and growling, doing nothing and, instead of work, some of the Boys go to sleep, some eat and drink all day; and Lord knows, I am bothered out of my wits.”[105]

The credit crisis caused the common man to shift how they made and received payment for goods. This same well-to-do farmer reflected on the preference for specie (money in coin) when he remarked that “Uncle George’s men will sell for cash alone; and where shall they raise it? Nobody wants vegetables or weeds.”[106] In this agrarian economy with suddenly low commodity prices, farmers could choose to plant and sell for low prices or try to find other productive work and let the land go to the weeds. The ability to store the value of crops became more difficult due to fears of default on trade credit and low levels of reliable currency or specie available. Even the US Mint found itself without deposits of gold and silver and was unable to operate at times throughout the year 1820.[107] If Turner was accurate in his assessment that prior to the 1822 construction of their frame home the Smith family’s farm work was done in a “slovenly, half-way, profitless manner,”[108] his assessment needs to be viewed with this additional context.

During 1820, public discourse centered on the economic collapse. One individual, referred to as “Eugenius,” reflected on the hardships while observing farm laborers from his window. He experienced a peculiar dream wherein people gathered on a plain to exchange luxury and extravagant possessions for items embodying simplicity and industry. A towering pile held these articles, and individuals from all classes arrived, some with only their clothes. They were guided by “the direction of one, who seemed to me to be of a superior order of beings.” A dandy exchanged fashion for humble attire and tools, while a pettifogger reluctantly carried a plough. As everyone engaged in productive work, smiles of contentment replaced sadness, highlighting the joy derived from hard work and humility over luxury. The American people needed to return to hard work and the values of the past.[109]

It was at this time, in the spring of 1820, that Joseph Jr., “by searching the scriptures,” concluded, as his father had almost a decade earlier, that “mankind did not come unto the Lord but that they had apostatized from the true and living faith, and there was no society or denomination that built upon the gospel of Jesus Christ as recorded in the New Testament.” For the prior three years, Joseph had been pondering these matters, “concerning the sittuation of the world of mankind the contentions and divi[si]ons the wicke[d]ness and abominations and the darkness which pervaded.”[110]

Although religious fervor in Palmyra has been well-documented in and around 1824,[111] scholars have debated over evidence available for religious excitement in Palmyra in 1820.[112] But 1820 was certainly a time of religious excitement for many, not only in Palmyra. The Geneva presbytery published that “during the past year more have been received into the communion of the Churches than perhaps in any former year.”[113] Indeed, Richard Lloyd Anderson quoted William Smith’s late sermon in which he noted that the revival “spread from town to town, from city to city, from county to county, and from state to state.” Joseph Smith’s 1838 account recorded that “the whole district of Country seemed affected by it.”[114] This likely included the ongoing nationwide discourse about the causes of the hard times, the comet and other astrological signs, and the conflict of opinions about how to save themselves from the constant stream of God’s judgments.

Rothbard further related the mindset of many of the citizens during this depression:

Similar to the theme that individual moral resurgence through industry and economy would relieve the depression was the belief that renewed theological faith could provide the only sufficient cure. . . . Typical was the (Annapolis) Maryland Gazette, which declared that the only remedy for the depression was to turn from wicked ways to religious devotion. A similar position was taken by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church, which found the only effectual remedy in a resurgence of religion and its corollary moral virtues.[115]

One might imagine the anxiety, despair, and insecurity the Smith family would have experienced at this time, having no hope of profiting from farming due to the great collapse of commodity prices, seeing the great number of people competing for jobs, the scarcity of money, and the various factions arguing over how to relieve these judgments of God portended by celestial signs.

Joseph Jr. recalled that during this “time of great excitement [his] mind was called up to serious reflection and great uneasiness.”[116] In line with economist Jeanet Sinding Bentzen’s study, which suggests that people tend to turn to prayer in times of uncertainty and adversity such as the COVID-19 pandemic,[117] perhaps Joseph pondered how his sins might have played a role in their difficult circumstances, which were underscored by clear signs of God’s judgments and widespread upheaval. Yet, after examining various religious teachings and finding none that fully aligned with the Bible, he grappled with how to proceed. Driven by a desire for greater religious devotion and perhaps hoping for relief from his family’s desperate circumstances, Joseph went to the Lord to seek forgiveness for his sins.

Seekers like Joseph Jr. and others like Betsey Carrol of northwestern Vermont found that “their natural surroundings intensified secret prayer. The woods could be a place of revelation.”[118] After Joseph’s supplication to the Lord in the grove, Joseph later described seeing the Lord in a pillar of fire and receiving forgiveness. The Lord also revealed to him what many probably were saying at the time: that “the world lieth in sin at this time, and none doeth good, no, not one.”[119]

Perhaps young Joseph pondered why people doubted these omens as superstitious and whether spiritual gifts had been lost due to the obvious wickedness and worldliness he experienced every day. His family was known to be a spiritualist family, part of a subset of people who believed that “superstitious” practices were not imaginary or deceptive. A similar view was held by one identified only as “a Querist” in 1826:

I have reason to believe that many arts, which we call “cabalistic,” are lost, merely from the skepticism of modern philosophers. . . . Egypt and other countries shew vestiges of arts which are lost. . . . [T]he arts of witchcraft, conjuration, prognostication, palmestry, the interpretation of dreams, &c &c no doubt were based in natural philosophy, and might have been accounted for by a process of natural reasoning, had they been thought worth investigating.[120]

Historian Jason Coy noted that “After the Reformation ended, Protestant and especially Calvinist, theologians . . . complain[ed] that divination practices undermined proper faith in God’s providence and challenged the clergy’s exclusive role in interpreting signs of the divine will.” Also, “most Lutheran authorities viewed astrology as a direct challenge to faith in God’s plan.” In the late seventeenth century, Protestants sought to purify the community of Catholic and pagan “superstition” and by the 1800s had been particularly successful with the demonization of divination.[121] This falling away from these spiritual gifts was probably concerning to Joseph, particularly with the signs during his lifetime that celestial omens carried real consequences.

The emergence of Shakerism had led many to equate miracles, visions, revelations, and superstitions as means “by which the elders obtain[ed] unlimited sway over the minds of their subjects.” Consequently, terms like “magic” and “superstition” had been politicized as being antirepublican and associated with those “open to imposters and con men, who would steal both money and freedom.”[122] Historian Adam Jortner noted that when Abner Cole began printing excerpts of The Book of Mormon in his newspaper, he reassured his readers that “we cannot discover anything treasonable, or which will have a tendency to subvert our liberties,” as if he expected his readers would anticipate such content.[123] Although ceremonial magic, divination, and witchcraft were employed among a subset of citizens in the 1820s, these practices had generally lost credibility during the Enlightenment and, whether fair or not, were not widely viewed favorably at the time. Faith in “witchcraft, fortune-telling, lucky and unlucky days, astrology, ghost stories, second sight, fairies, and omens” were declared as extinct, or at most, “confined to the nursery”[124] by some, but in another account it was observed that “pretending to tell fortunes had become so common, that there is scarcely an old maid or a gossip but will pretend to show you the events of your future life.”[125]

Unable to farm for profit, the Smith family turned to alternative sources of income, some traditional and some unconventional. They engaged in various manual labor jobs such as harvesting maple syrup and selling cake and beer from a cart on special occasions.

They also produced baskets, brooms, and cord wood, which were traditionally known to be Native American goods and subsidized by the Presbyterian Synod a few years earlier.[126] Natives typically lived off the land and had few resources. Likewise, basket makers in New England were known to be of a marginalized class, living on the edge of society, often in swamps and shacks. The manufacturing census of 1832 in Maine noted that “the basket makers are indigent persons, living in the back part of the town, on rocky sterile land, who employ themselves in making baskets, as the only means of affording a living.”[127] Manufacturing these goods was a simple skill to learn and required little upfront investment, but it was tedious and unprofitable work.[128] The fact that the Smiths manufactured these items suggests their extreme poverty and lack of alternative options. It may even reveal an early relationship of the family with the Presbyterians who recommended people purchase these items to support Native Americans.[129]

In addition to these goods, Joseph Smith Sr. dug and peddled “rutes and yarbs”[130] perhaps led with a divining rod, a method historian Mark Staker and curator Don Enders have suggested ginseng collectors in Vermont sometimes used.[131] Finding roots and herbs was an activity he had in common with Luman Walters, an eccentric witch doctor, who, according to D. Michael Quinn, would later become an occult mentor to young Joseph. Walters was said to have “engaged several men to gather various roots, such as burdock, mustard and other forms of vegetation which he compounded into medicine at his laboratory.”[132] Lucy Smith administered remedial roots and herbs “when her lowly neighbors were sick or dying.”[133]

Joseph Smith Jr.’s contributions to the family’s economic self-sufficiency during the Depression have been a subject of debate. Quinn contended that Joseph ventured considerable distances in search of employment as a treasure seer, potentially extending to Seneca and Broome Counties in New York, as well as Susquehanna County in Pennsylvania. Others such as Dan Vogel tend to disagree primarily due to the late and sometimes inconsistent accounts of his presence there until later and a lack of contemporaneous evidence.[134]

Shortly after Joseph Smith’s prayer, an important economic event transpired in Palmyra. In May 1820, local economic conditions can be gleaned from a Canandaigua newspaper, which reported on contracts being offered for the construction of a ten-mile section of the canal that was planned to pass through Palmyra. A substantial number of people, eager for employment, descended on Palmyra in pursuit of these contracts:

The contracts were mostly taken by citizens from the neighboring towns, and at prices somewhat lower than have heretofore been given. The great scarcity of money among us, the abundance and cheapness of provision of all sorts, for the subsistence of men and cattle, and the low price of labor, produced an extensive competition for taking jobs, among our citizens . . . The contracts were made at Palmyra, where, we understand, were collected for the purpose of making proposals, near four hundred respectable people, of different occupations and employments.[135]

The essential requirement for the canal was adequate water. In the same month when canal contracts were granted in Palmyra, the London-based Quarterly Review published an article that seemingly endorsed the use of divining rods as a legitimate method for locating water sources.[136] This ignited a contentious debate in numerous US newspapers, with one publication remarking that “the newspapers have lately been much occupied” with the topic.[137] One correspondent expressed the hope that Dr. Samuel L. Mitchell, whose name would later become associated with the story of Mormonism,[138] would offer his insights on the divining rod controversy.[139] Despite its controversial nature, the use of the divining rod was reportedly “religiously believed by thousands of persons both in Europe and America.”[140]

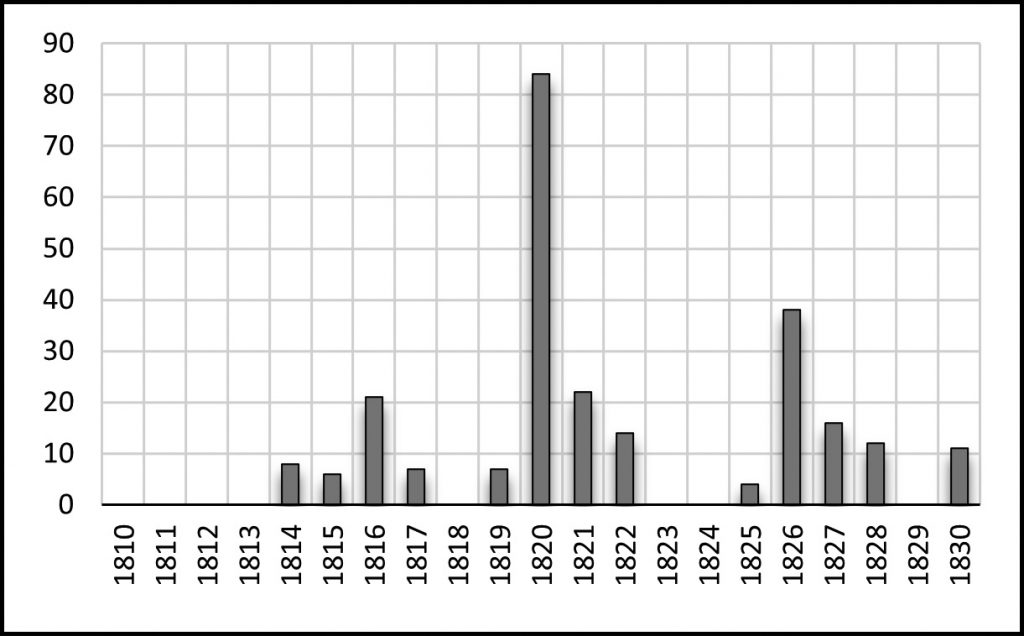

A search in the GenealogyBank.com newspaper database for the term “divining rod” reveals a significant surge of interest in the divining rod during 1820.

Figure 9: Number of pages in GenealogyBank.com newspaper database mentioning “divining rod,” 1810-1830.

The use of the divining rod may have played a role in identifying water sources along the Erie Canal. The western segment of the Erie Canal, including through Palmyra, extending from Cayuga Lake to Lake Erie, was known as the “dry division” by canal commissioners. Although the Genesee River supplied a substantial amount of water, dry spells during the summer months affected water flow, creating challenges for lock operations and canal water levels,[141] making Governor DeWitt Clinton and his “ditch” the subject of ridicule from his political opponents.[142] Ensuring an adequate water supply to supplement the Genesee River to maintain canal depth, operate locks, and provide fresh drinking water for the workforce in Palmyra became of utmost importance during these two years.[143] It seems plausible that during this period, individuals with dowsing abilities were highly sought after by those who believed in the rod’s efficacy.

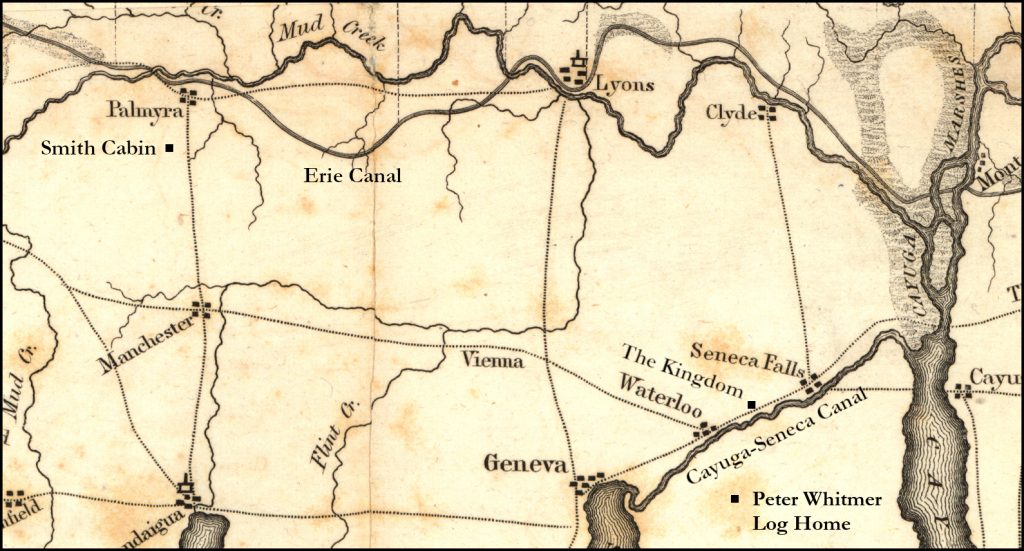

Figure 10: Partial map of Ontario and Seneca Counties, with added notation of locations relevant to the Smiths. Adapted from Map and profile of the Erie Canal: commenced 1817, finished 1825, 1825, map, NYS-[1825?].Fl; Map Collection, Brooklyn Public Library, Center for Brooklyn History.

In the year 1820, during a period when the divining rod was a popular topic and the demand for water was pressing, Joseph Jr. was first documented to specialize in the practice of using the divining rod to locate water. One late source indicates Joseph left his father’s house at age fifteen, which would have been late 1820 or 1821.[144] This is supported by the fact that the 1820 federal census did not list Joseph Jr. as being present in his father’s Farmington home as well as a notice published in the Waterloo Gazette in July 1820 listing that a letter to Hyrum Smith remained in the Junius post office, which, in 1820, was located in Waterloo.[145] Ernest L. Welch and Harrison Chamberlain, whose father Jacob had enlisted Joseph Jr.’s services, remembered that Joseph resided for a time in The Kingdom, between Seneca Falls and Waterloo, around 1821 or 1822. Welch remembered he worked “as a general hand for any kind of work; but engaged chiefly in finding water with a switch carried in his hand.”[146] Another resident of Seneca Falls, reflecting on Joseph Jr., described how in 1820 their town was “visited by an odd-looking boy, clad in tow frock and trowsers, and barefooted. . . . [He] made a living by seeking hidden springs.”[147]

The peculiar practice of going barefoot may have been a result of both poverty and the customs of dowsers who believed that moistening their feet with saltwater or diluted muriatic acid could heighten the connection between the dowsing rod and the water.[148] Bletonism, as it was called, was “the faculty of perceiving and indicating subterraneous springs and currents by sensation,” a method of searching by feeling, generally with a witch hazel switch.[149]

Between 1819 and 1821, significant operations were also underway in the construction of locks in Waterloo, The Kingdom, and Seneca Falls, integral to the development of what would later become the Cayuga–Seneca Canal.[150] If Joseph Jr. was indeed hired to locate hidden springs in Seneca Falls and The Kingdom, his water-divining activities might have had connections to the monopoly held by the Seneca Lock Navigation Company, which controlled land and water rights along the falls. The company had acquired all the adjacent land along the river and was known to deny leases to others, potentially creating a local need for supplementary freshwater sources or assistance in optimizing the operation of locks.[151]

However, specializing as a water diviner alone might not have provided a sufficiently diverse range of work to sustain a livelihood during the Depression, prompting Joseph to apply his talents for other purposes that would ultimately elevate his notoriety. Frederic Mather suggested that “the profession of a water-witch did not bring enough ducats [i.e., gold coins] to the Smith family; so the attempt was made to find hidden treasures.”[152]

The period was marked by a rapid increase in the relative purchasing power of gold and silver, coupled with a growing interest in spiritual practices. This convergence of factors may have intensified the allure of treasure-seeking for the Smiths and other financially struggling families. As a result, Joseph would have received more incentive and opportunities to practice the skills his father taught him. This situation aligns with Stephen Harper’s study of treasure-seeking, revealing that in earlier days in Vermont, “financial stress drove a substantial group of settlers to ‘an unconquerable expectation of finding buried treasure in the earth.’”[153]

Neighbor Willard Chase recalled his initial encounter with Joseph Sr. and his family, reflecting that “first became acquainted with Joseph, Sen., and his family in the year 1820. . . . A great part of their time was devoted to digging for money; especially in the night time, when they said the money could be most easily obtained.”[154] The scarcity of money during the Depression caused rapid deflation and hoarding of specie. This caused a stark contrast between those with wealth denominated in gold, silver, or currency and those with assets in trade accounts, bank notes, debt-financed land, or provisions. The latter, being the most common assets, became less desirable as a means of exchange due to fears about the solvency of banks and debtors.

Ashurst-McGee also contended that finding treasure was less important to Joseph than finding lost property but was easier for his contemporaries to ridicule.[155] But the differentiation between the two is, perhaps, superficial because contemporaries often referred to finding lost property and treasure digging interchangeably.[156] The treasure-seeking for Joseph usually involved finding lost or stolen property that just happened to be underground. Captain Kidd’s treasure, for which Joseph Jr. was said to have had an interest, was lost, stolen, and supposedly buried underground, and the gold plates were also purportedly long-lost property. “In 1826 an astute observer noted that ‘from north to south, from east to west’ many ‘respectable’ men ‘of large information, and of the most exemplary lives’ continued to believe that divining rods could detect underground water; but ‘in all parts of the land, if the diviner hunts for metals, he becomes distrusted by the better sort of men.’”[157]

Joshua Stafford mentioned in about 1819 or 1820 that the Smiths “were laboring people, in low circumstances. A short time after this, they commenced digging for hidden treasures, and soon after they became indolent, and told marvellous stories about ghosts, hob-goblins, caverns, and various other mysterious matters.”[158] But the divining rod had limited operational range. At some point between 1819 and 1822, Joseph Smith began using a seer stone “in place of the witch hazel.”[159] His father reportedly had expressed a desire to help him find one that he could use to “see all over the world” rather than being limited to a local area with a divining rod.[160]

Although many have criticized Joseph’s practices to point at him as a deceiver, some or all of his practices may or may not have been intentional deceptions despite their illegality. Mysterious phenomena, such as rocks appearing on field surfaces each spring—a periglacial process common in New England now understood to result partly from frost heaving—may have reinforced beliefs about Earth’s mystical nature, including the idea that buried treasures could rise or sink in response to natural or spiritual forces.[161] Joseph’s brother-in-law and critic Alva Hale would later express that Joseph Jr. told him he “was deceived himself but did not intend to deceive others.”[162] Magical practices aimed at finding treasure or recovering lost or stolen property have been documented for centuries, with many individuals incorporating these practices into their Christian belief systems.[163] In the distant past, even royalty granted licenses to treasure-seekers, and priests were known to have summoned spirits to help them locate hidden treasures.[164]

Ashurst-McGee also noted that “Joseph Capron, one of Hurlbut’s antagonistic informants, asserted that Joseph communicated with ‘ghosts’ and ‘infernal spirits’ that appeared in his stone.”[165] Ancient practitioners of ceremonial magic invoked creatures from the celestial, terrestrial, and infernal realms,[166] intertwining the natural and the supernatural worlds. They called upon the spirits, intelligences, and archangels[167] who were believed to act as intermediaries with God or the planets.[168] For example, one ancient “experiment,” in line with one of Joseph’s objectives of finding stolen property, sought to compel a thief to return stolen property. The procedures, which have faint parallels to Joseph’s first prayer and the finding of the gold plates, called for retiring to a secluded area in the woods and engraving the four cardinal directions on each side of a lead plate along with the accompanying names and signs of the spirits associated with each cardinal direction. The name of the thief would then be engraved in the center. The practitioner was instructed to bury the plate and then call upon these spirits and invoke the power of God through the nine orders of angels, including the thrones, principalities, powers, dominations, cherubim, seraphim, and others, to coerce the thief to change his ways and return the property. If this didn’t work, the practitioner should bury the plate with foul matter and burn it while summoning infernal spirits to torment the thief to repentance.[169]

Although there are no known credible references to lengthy historical records being written on plates of gold, ceremonial magic, as previously described, sometimes involved engraving metal plates made of lead, silver, iron, brass, and even gold with characters, symbols, words, and sigils.[170] However, these plates were generally single metal plates. These “lamens” (Latin for plate) were traditionally made of the metal associated with specific planetary intelligences and sometimes worn as a breastplate, talisman, or amulet. However, “virgin parchments” such as the magic parchments that reportedly belonged to the Smiths and were passed down through Hyrum’s family were also used if the metals were too expensive or unavailable.[171]

Remnants of these traditions may have perpetuated and informed Joseph’s methods in “many instances of finding hidden and stolen goods,”[172] as his upbringing was steeped in echoes of the mystical culture of the ancient past, and he may have believed that these spiritual gifts or hidden truths had been lost to apostasy. The family was said to practice, experience, or attempt many spiritual practices. Ashurst-McGee writes that divination activities ascribed to Joseph’s parents included “hearing the voice of Christ, visionary dreams, dowsing, astrology, numerology, palmistry, amniomancy, and the observation of omens.” Lucy also was an interpreter of dreams, and Joseph Jr. indicated some belief in astrology.[173] Some even claimed that Joseph Jr. believed in witchcraft,[174] although it’s debatable as to whether he practiced it. Brigham Young, who later recommended against favoring astrology nonetheless noted that “an effort was made in the days of Joseph to establish astrology,”[175] and disaffected Mormons hyperbolically echoed that “the only thing the Prophet believed in was astrology.”[176]As the family explored these alternative avenues of monetary support and spiritual connection, seeking additional light and guidance in their dark days, they ran afoul of both public skepticism and laws intended to discourage “unorthodox spiritual traditions” based on early European anti-witchcraft legislation.[177]

Although Quinn noted and Ashurst-McGee later reasserted that “for the treasure-seer the primary reward was expanding his or her seeric gift,”[178] the financial motivation should not be overlooked, particularly due to the financial pressure of the time. In much earlier days, there was no shame in charging a fee to perform divination activities. Treasure-seeking groups had characteristics of both business enterprises and religious congregations, diverse groups seeing themselves taking somewhat the role of clergy in a mission to aid the spirits of the dead in a cosmic struggle against good and evil, demons seeking to drive away the treasure-seekers from aiding in the spirits’ deliverance.[179] But during this time period, the high fees charged even by water dowsers for their services were viewed as “imposing on the credulity of their neighbors.”[180] However, the documented successes of dowsers were challenging for people to dismiss, primarily due to their limited understanding of the prevalence and characteristics of subterranean water. Some regarded the actions of the rod as a natural phenomenon, while many considered it a delusion. In contrast, Joseph Smith seemed to believe it was a spiritual practice and a means through which God communicated.[181]

Joseph’s immediate vicinity was home to many seers. But many did it only in secret. Joseph’s father was probably his closest tutor, having reportedly been involved in money digging far earlier than Joseph Jr.[182] Future convert and bodyguard Porter Rockwell perceived that “The most sober settlers of the district . . . were ‘gropers’ though they were ashamed to own it. . . . Joseph Smith was no gold seeker by trade; he only did openly what all were doing privately; but he was considered to be ‘lucky.’”[183] This probably elevated his ability to charge money for it. According to the 1828 Webster’s dictionary, a groper is “one who feels his way in the dark, or searches by feeling.” This would perfectly describe the theology Smith would later establish: adherents feeling their way toward truth through a burning in the bosom. Such mystic practices would resonate with some spiritualists but would cause conflict of opinions with many deists and evangelicals. One critic, writing in 1804, lamented that revivalism caused men to “conclude this or that doctrine to be true or false, not because they find or do not find it in the holy scriptures; but because they felt so and so, when praying.”[184]

However, there is little in the way of contemporary evidence about how much the family earned from these activities. Late accounts recall payment of seventy-five cents to Joseph for divining the location of stolen cloth,[185] or unspecified amounts for divining where a chest of gold was buried and telling fortunes.[186] One account mentions that he earned fourteen dollars per month as a seer, but this probably refers to the later employment by Josiah Stowell in 1825.[187] As a benchmark, the backbreaking work of digging the Erie Canal paid a meager twelve to thirteen dollars per month in 1819.[188] Joel K. Noble, a justice of Joseph Jr.’s second 1830 trial, recounted that the defendant testified he “says anything for a living I now and then get a shilling,”[189] which phrase seems to coincide with the desperate situation in which Joseph lived and the limited profitability of his sporadic money digging, even though the family reportedly engaged in it “to a great extent.”[190]

Some neighbors believed the Smiths creatively hatched schemes in order to feed their family. It was not uncommon to hear stories that Joseph’s real motivation in obtaining sheep to sacrifice in treasure-digging ventures was to obtain a meal of mutton.[191] The neighbors often had their sheep and poultry go missing, so they would call officers to search the Smith property. Rumors emerged that the creek near the Smith’s house was lined with the heads and feet of stolen sheep.[192] Joseph’s brother William would later vehemently deny these accusations, contending that they were not sheep thieves.[193] However, former associates from Vermont would later reflect similar sentiments that one of the reasons for Joseph Sr.’s departure from their area was due to his “being too extremely fond of mutton.”[194]

In this environment with evidence of the reality of omens, constant toiling for survival, and conflicting opinions of priests who had rejected the supernatural communications with God, Joseph began his journey toward seership. Joseph may have been enticed by the lore, traditions, and practices of this belief system that merged ancient but socially stigmatized magical practices with protestant Christianity. This enticement may have been especially acute given the desperate and ominous times he lived in. His faith in the traditions he knew probably drove him to practice these skills, seeking additional sources of guidance, protection, and support in a world where the gifts of God seemed to have been lost. He may have even pursued these supernatural means to advance what he perceived was his purpose in life. Joseph Jr. later recorded, “My Grandfather Asael Smith long ago predicted that there would be a prophet raised up in his family, and my Grand Mother was fully satisfied that it was fulfilled in me.”[195]

The Smith family’s financial struggles, marginalization, and lack of viable options for employment forced them to adapt to and find alternatives to traditional agricultural pursuits. The financial pressure, ominous signs, and turmoil led the whole nation into a search for spiritual renewal, and through the hard times, the family supplemented their income with ventures that differentiated them from the masses of people desperate for work. Joseph’s specialty and goals seemed to center around reviving ancient gifts some believed had been long lost from the earth.

Through reflection on the Smith family’s economic and spiritual environment throughout the Panic of 1819, Joseph Jr.’s work with the divining rod and seer stones makes more sense from both an economic and a spiritual context. The continuous signs in the heavens and on earth during his upbringing triggered anxieties and revived a nationwide renewed interest in connecting with the divine. These influences help us understand the family’s course of actions and shed light on why a boy who allegedly saw God would nearly immediately become involved in practices many today perceive as errant and deviant.

Appendix 1: Transcription of Canandaigua Court, Docket Entry, August 19, 1819

Figure 11: Transcription and assembly of Docket Entry, circa Aug. 19, 1819, “Jeremiah Hurlbut vs Joseph Smith Sr. and Alvin Smith.”

Replacing the “The Like” with the reference text produces the following:

The defendants default in not pleading having been duly entered on motion of F Smith Atty for Plaintiff ordered interlocutory judgment and that the Clerk assess the Damages.[196]

Appendix 2: Canandaigua Court, Common Rule Book Entry, July 31, 1819

Figure 12: Canandaigua Court, Common Rule Book, entry for July 31, 1819, showing default judgment was entered.

Transcription of Canandaigua Court, Common Rule Book Entry, July 31, 1819

Figure 13: Transcription and assembly of Canandaigua Court, Common Rule Book, entry for July 31, 1819, “Jeremiah Hurlbut vs Joseph Smith Sr. and Alvin Smith.”

Replacing “The like” with the reference texts produces the following:

Jeremiah Copy Narr[atio] + notice of rule to plead being duly

Hurlburt served in this cause more than 20 days since + No plea

Vs being received On motion of F Smith attorney for plffs

Joseph Smith + ordered that the defendants default be[ing] the same is Alvin Smith hereby entered for want of a plea

[1] William S. Burroughs, The Western Lands (New York: Viking, 1987; reis., London: Pan Books, 1988), 116.

[2] This article departs from conventional academic practice by referring to members of the Smith family by their first names. Given the frequency of references to multiple individuals within the Smith family, this approach is intended to minimize ambiguity and enhance readability.

[3] “The Comet,” Vermont Percursor (Montpelier), Oct. 30, 1807, [3], https://www.newspapers.com/image/490742086/; “Inhabitants of Comets,” Kinderhook Herald, May 7, 1829, [1–2], https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&=kh18290507-01.1.1, quoting David Milne-Home, Essay on Comets: Which Gained the First of Dr. Fellowes’s Prizes, Proposed to Those who Had Attended the University of Edinburgh Within the Last Twelve Years (Edinburgh: A. Black, 1828), 142–45; “Items,” The Geneva Gazette, and General Advertiser, June 17, 1829, [1], https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=tgg18290617-01.1.1; “Germany,” The Troy Sentinel, Nov. 3, 1824, [2], https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=tts18241103-01.1.2; Esther Inglis-Arkell, “Astronomers Once Thought There Was Life on the Sun,” Gizmodo, Dec. 20, 2013, https://gizmodo.com/astronomers-once-thought-there-was-life-on-the-sun-1487292730.

[4] Mark L. Staker and Donald L. Enders, “Joseph Smith Sr.’s China Adventure,” Journal of Mormon History 48, no. 2 (2022): 79–105.

[5] Staker and Enders, “China Adventure,” [79].

[6] Royalton Vermont Town records, 1788–1880, digital image, FamilySearch.org, citing FamilySearch microfilm 982526, items 3–5, 318; “Vermont State News,” The Vermont Watchman and State Journal (Montpelier), May 14, 1884, [1], https://www.newspapers.com/image/71218953/. Joseph Smith is a common name, but no other Joseph Smith appears in the Royalton town records during this period. The warning out may have been ordered as a common preventative measure to keep people from being a burden on the town. Due to appearances of his name in subsequent years, it appears the selectmen allowed the family to stay in Royalton until at least 1811.

[7] Shelby M. Balik, Rally the Scattered Believers: Northern New England’s Religious Geography (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014), 74–109.

[8] Amanda Porterfield, Conceived in Doubt: Religion and Politics in the New American Nation (Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 2.

[9] William Smyth Babcock journal, Jan. 20, 1802, William Smyth Babcock Papers, folder 3, cited in Balik, Rally the Scattered Believers, 118. The preacher was William Babcock, an itinerant Freewill Baptist preacher among the hills of Vermont who later married Betsey Merrill of Springfield, Vermont. She was a woman who claimed to have seen angels and had visions while in a trance beginning in 1805. Mark Bushnell, “History: Angel over Springfield,” Rutland Herald (Vt.), July 24, 2004, https://www.rutlandherald.com/news/history-angel-over-springfield/article_48cc0428-b7ef-5c64-81b0-8e1aa10a690e.html.

[10] Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1844–1845, book 2, page 5, Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/lucy-mack-smith-history-1844-1845/23.

[11] Green Mountain Boys to Thomas C. Sharp, Feb. 15, 1844, as transcribed in Early Mormon Documents, vol. 1, edited by Dan Vogel (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1998), 597. Later citations will use the abbreviation “EMD,” followed by volume and page numbers. The Green Mountain Boys replied to Joseph Smith Jr.’s appeal for help, claiming Joseph Smith Sr. said “Voltairs writings was the best bible then extant, and Thomas Paine’s Age of Reason.”

[12] Porterfield, Conceived in Doubt, 14, citing Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason (Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1974; orig. 1794 and 1795), quotations from 60, 68, and 54–55.

[13] Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, 52–53, Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/lucy-mack-smith-history-1845/59.

[14] Ibrahim Ali Mahomed Hafez, pseud., The oneirocritic: being a treatise on the art of foretelling future events, by dreams, moles, cards, the signs of the zodiac and the planets (New York: Printed for N. Ogden, [between 1790 and 1799?]). Note: Name is spelled “Ibraham” in some records. Many other books and editions were published during the period that claimed similar interpretations of fortunes. See also Ibraham Ali Mahomed Hafez, pseud., The New and Complete Fortune Teller (New York: Richard Scott, George Largin, 1816), https://www.loc.gov/item/11014336/; and Every Lady’s own Fortune-Teller, or an infallible guide to the hidden decrees of fate, etc. (London: J. Roach, 1791). See topics of corn, 38; fields, 48; turnips, 88; wheat, 89; bulls, 32; dogs, 43; and eating, 45.

[15] Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845, 52–53.

[16] “Comet,” Pennsylvania Gazette, June 12, 1811, [3], https://www.newspapers.com/image/41024720/.

[17] “Foxter’s Letter,” Oswego Daily Palladium, Oct. 1, 1892, 6, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=tdpl18921001-01.1.6.

[18] “The Comet,” The Washingtonian (Windsor, Vt.), Sept. 16, 1811, [3], https://www.newspapers.com/image/489834244/.