Articles/Essays – Volume 25, No. 3

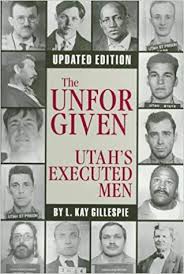

Utah’s Darkest Side | L. Kay Gillespie, The Unforgiven—Utah’s Executed Men

Readers of L. Kay Gillespie’s exposition about Utah’s unforgiven should find it thought-provoking—at times, disturbingly so. The picture he paints here is of Utah’s darkest side: the deliberate brutishness and ugliness on both sides of the law in matters of life and death, crime and punishment, justice and injustice. Framing the elements in this collage are Mormonism’s past preachments about the doctrine of blood atonement. For better or worse depending on one’s perspective, Utah stands as a small (forty-seven executions) but sincere champion of capital punishment.

To help interpret this array of images, Gillespie first leads readers into the trou bling moral and practical issues posed by lawful bloodletting. He presents an overview of an actual execution and the extensive preparations required to do it right on the first try. Once a key player in these actions, he somberly reflects: “There is no humane way to execute, but we pretend there is” (p. 2). If true, what is there about the concept and utility of this ritually bound practice that justifies the act? What makes capital punishment appealing enough to support it in principle or practice?

Gillespie offers an answer based on the philosophical principle of social utility—general deterrence. “After all,” he says, “the purpose of any social sanction is to assure future compliance with and respect for law.” This objective cannot be obtained, he opines, “if those who are the objects of societal punishment are forgot ten and deaths never reviewed” (p. 9). By telling the stories of Utah’s unforgiven, the author hopes to create a psychodrama in the readers’ minds, to stimulate people to seek improvements in matters of due process that might make capital punishment more palatable. Perchance, by vicariously expressing our willingness to actually pull the noose taut around a few evil necks, we might experience enough discomfort to “see to it that society does not carelessly toy with those lives it chooses to forfeit” (p. 9).

Two related issues cannot be side stepped in any serious consideration of crime and punishment in Utah. First is Mormondom’s doctrine of blood atonement, including the moral or ethical strength of the Church’s current stance on the death penalty. Second is the unique role the Church plays in dispensing Utah justice. Though the Church hierarchy of this era has denied that blood atonement was ever an official doctrine meant for this dispensation, Gillespie stresses that the matter still lies heavy in the minds of many Latter-day Saints. Some early Mormon leaders powerfully promoted the concept of blood atonement, among them Heber C. Kimball, who claimed it was an “excellent thing for this people to be sanctified from such persons, and have them cleansed from our midst, by making an atonement” (p. 13).

The vagaries surrounding the doc trine’s official or unofficial status notwithstanding, the concept has been officially rationalized to fit any type of cleansing motif Utah ever offered its doomed killers. Thus, those executed in the future need not concern themselves about the necessity to literally shed their blood as an atonement, as was Arthur Gary Bishop, executed in 1988. Interestingly, no one ever took the state up on the once available beheading option. Perhaps the thought seemed too atrocious, despite the great inconvenience guillotining would cause the state. Inconveniencing the state was the desire of the most bitter of offenders in choosing death by hanging. And obtaining a guillotine and an executioner skilled in its use would have been even more troublesome than constructing a gal lows and hiring a professional hangman.

With the issues of blood atonement set in the background, the remaining chapters reveal a measured tour de force that tracks Utah’s mountain-style justice since 1847. Some facts, figures, and encapsulated case studies unveil a black, sometimes outright gory, history at times involving wanton bloodshed and legally sanctioned killing. Sketched out are the highlights surrounding the abhorrent deeds, trials, convictions, sentencings, and societal reactions. Gillespie does not overlook the ritual last meals, final wishes, and words uttered by the damned. We get a look at botched executions and the death throes of forty-seven formally condemned men (Utah has yet to execute a woman). In addition to this relatively small number of official executions is a brief overview of several unofficial or vigilante-style executions. The final two chapters review everyday life on death row for both the inmates and the jailers, a miniature of those who rightly or wrongly escaped paying the ultimate price for their crimes and a brief glimpse of other executions and prison sentences.

Gillespie finishes without finishing, without answering the “many nagging, unanswered questions about the place of capital punishment . . . questions about the why’s and how’s of crime; about trials, guilt and sentences; about what it means” (p. 198).

Considering the bleak nature of the subject, this book is very sensitively writ ten. It begins to bring together under a unifying umbrella scattered but important pieces of Utah history. Its shortcomings lie in what goes largely untapped or weakly exploited. More specifically, Gillespie says too little about a number of issues and questions raised about a church, a state, and its people. Perhaps the most significant of these is the insufficient explanation of justification of the book’s pro-capital punishment slant. Using the justification of social utility or general deterrence cannot wash away the stain of moral embarrassment that societal punishment leaves without showing that we accomplish a greater good. And that is unverifiable. There are more substantial and morally plausible grounds upon which to justify the death penalty.

The last strokes brushed on the canvas predict that Utah will “no doubt continue to sanction capital punishment” (p. 198). To follow the author’s lead, this is probably true. For in Utah, Mormonism’s early religious baggage and its current sanctioning of capital punishment powerfully attune the state toward acceptance of this picture.

The Unforgiven—Utah’s Executed Men by L. Kay Gillespie (Salt Lake City: Signa ture Books, 1991), 199 pp., $18.95.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue