Articles/Essays – Volume 28, No. 1

Wallace Stegner: The Unwritten Letter

I remember well the first time I met Wallace Stegner because I wanted so much to prove him wrong.

The place was the University of Utah, a room in Orson Spencer Hall. The year was probably 1960 or 1961. Someone on the faculty had invited Stegner, one of the U’s better-known alumni, to talk informally with English majors and student writers. I qualified on both counts.

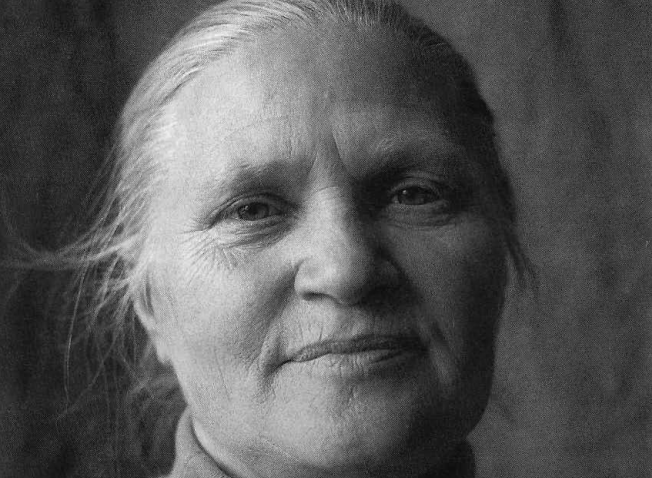

Stegner appeared to me then the way he would always appear to me—handsome, erect, white-haired, modest, and gently cynical. In response to a question I asked, he said he wasn’t optimistic about the possibility of a Mormon best-seller. He shook his head. “It takes too much explaining.” He was an outsider who knew the lingo, but we couldn’t expect other outsiders to understand. Like me, he had spent his adolescence and early adulthood in Salt Lake City and he had great affection for the place, but I could tell he was glad that Mormonism wasn’t a faith he’d been saddled with. Something inside me bristled. A Mormon could write

Mormon fiction for The New Yorker. I just knew it was possible. The spring of my senior year, I won a fellowship that would pay my way to any graduate school that would take me. In 1962 there were only two graduate schools of real interest to a young writer—and I didn’t want to go to Iowa. I sent Stanford my application and some short stories, set in the places I knew best—southern Nevada and northern Utah. I waited nervously, impatiently. Finally I got word that Stanford and Stegner had accepted me in the writing seminar and the M.A. program. The U’s creative writing teacher, Brewster Ghiselin, always skeptical of my abilities, bid me farewell with the advice to be a scholar, not a schoolgirl. I packed my typewriter, books, and clothes, rented a second-floor studio on Palo Alto’s Cowper Street, and bought a three-speed bicycle with saddle baskets. I was ready.

Thirteen of us sat around the table in our room upstairs in the old Stanford library. I was one of two women and the youngest and shyest person there. Only the man speaking wasn’t making eye appraisals of his companions. Balding and bespectacled, he stuttered slightly, and his jaw jutted up and forward when he spoke. Stegner was in Vienna with a Stanford-abroad program. Richard Scowcroft would be our mentor for the fall quarter.

I knew something about Richard Scowcroft, something the others at that table didn’t know. Scowcroft, too, was from Utah, but he had been a Mormon. That knowledge made me nervous, here, away from home. At heart a doubter, I was trying very hard to believe. At the U, I had had several jack-Mormon teachers, but if they were interested in my religious beliefs, they never let on. But here, at a party at the Scowcrofts’ home, Scowcroft was squatting beside my patio chair. “You don’t really practice Mormonism, do you?” he asked. I grunted. His jaw jutted forward and then dropped. “How can you do that?” I flushed, hunched over my knees, and made an unintelligible noise.

Sensing my vulnerability, Scowcroft was gentle in his criticisms of my stories. There had been a pause after he had read my first story to the group, and then someone breathed out and said, “Hey, that’s good,” and others chimed in. During the discussion, no one but Scowcroft knew it was mine, and I think Scowcroft was as surprised as I at the praise. That was one bright spot in a difficult quarter—I had no facility for Old English, and I worried a lot about Albert Guerard’s Wordsworth seminar and the Cuban Missile Crisis and my new boyfriend, who seemed to me very old and very intense and who, though he was disguised in the fluffy white garments of a returned missionary, had turned out to be a wolfish unbeliever. I welcomed the end of the term.

Winter quarter Stegner appeared in our seminar room. Unlike Scowcroft, he announced who had written a piece before he read it aloud, so we concentrated on the story instead of asking ourselves, “Is this Michael’s? Is this David’s?” When he returned a story to me, there was often at least a full page of comments, typed, single-spaced. Only once was there a single paragraph. I had tried to write about my Seventh-day Adventist landlady and her wheelchair-bound and paralyzed husband. From my window, I often watched her scooting him about on the back porch. I was convinced that he was dead and that she had somehow preserved him like a stuffed parrot. The story didn’t work. “It’s a young per son’s view of age, it’s cooked up, not felt,” Stegner wrote. I went back to writing stories about young persons.

I had just turned twenty-two. That quarter I was troubled by Ivor Winters’s Milton-bashing lyric poetry course and the rains that drenched me as I rode my bike down Palm Drive, but I had a new boyfriend (more intense and even older than the previous one—twenty-seven, but a genuine convert to the gospel) and I was almost comfortable in the seminar room and at the parties at the married writers’ homes, where an absence of furniture meant that we sat on the floor. The hosts would buy a six-pack of ginger ale for me, and I would dutifully drink a couple and then, full of sugar water which I wasn’t accustomed to, would lean against the wall, listening in companionable silence. “Remember Captain Marvel?” someone would say, and everyone but me would shout, “Yeah!” “Did you send in two boxtops for his decoder ring?” “Yeah!”

“Do you think we can call Stegner ‘Wally’?” someone asked. “How do you think he lost his finger?” asked someone else. We would read and wisely discuss his stories. “‘Field Guide to Western Birds’ is brilliant,” said David Thorburn, the best critic among us. I preferred the “boy” stories, like “Goin’ to Town.”

The Stegners had a party too, to honor Saul Bellow, who had been on campus and who had met with our seminar during the week. I was enchanted by the Stegners’ wild, green hill and their comfortable, woodsy home. There were ample chairs and sofas and big china dinner plates to pile food on and plenty of food. “Put a little coffee in that little girl’s coke,” Stegner said as I balanced my drink on my plate. I nodded shyly at Saul Bellow. I hadn’t yet read The Adventures of Augie March, which David had assured me was one of the greatest of all American novels. The oth ers gathered around Bellow. I found a couch seat and tried to listen. Later, when it became evident that I wasn’t going to burrow into the circle, Stegner brought Bellow over to talk with me.

One day I set out for school as usual on my bicycle. Speeding down the side of a Palo Alto business street, I ran into a car door that suddenly opened. I straddled my bicycle, stunned, as the driver and a group of passersby gathered around. “I think I’m all right,” I said and put my hand up to my face. It was covered with blood. Someone locked my bike to a lamp post, and two policemen put me in the back seat of their car and drove me to the campus infirmary. The resident taped the slit under my lip. I had missed my morning classes but headed over to the creative writing seminar. I met Stegner on the library stairs. “What happened to you?” he said. By now my jaw had begun to swell, and I looked as if I had had my wisdom teeth yanked out. I cheerily explained that I was fine. “You are not fine,” he said. “Let’s get you home.” I protested but finally agreed to call my boyfriend to retrieve me.

By spring quarter the more confident writers—Mort Grosser, Ed Mc Clanahan, Bob Stone—had nervously started to address Stegner as Wally. I had no desire to imitate them. To me he was and would always be Mr. Stegner. Besides the seminar, I took a regular lecture course from him that term, one in the American novel, and there I discovered Willa Cather’s Death Comes for the Archbishop. I discovered some things about myself too—I had enjoyed all those reading list books set in England or Boston or the gothic South. But I, alone in my writing seminar, alone except for Wallace Stegner, was a westerner. I had to write about the West, the Mormon West. It was what I knew, what I was. And perhaps it was because Stegner was there that my little “western” stories were accepted, and I was accepted.

One of our last class meetings—it may have been at his home because we were outside—Stegner read us something he was working on. We listened carefully. I remember thinking it wasn’t ready yet, and I felt honored that he would share with us something that was that unfinished. I think it was the same afternoon that we heard part of Bob Stone’s novel, the one that would eventually be published as Hall of Mirrors, and Stegner wept a little at the power of the writing, and I wept a little at the power of the writing and at Stegner’s weeping.

Our last seminar began in our old seminar room in the library but ended with Stegner announcing he would buy us all drinks at a place on University Avenue. In his car he passed me and called out, “Want a ride?” Then he seemed to register that I was on my bicycle, and we both chuckled. I don’t remember much about the gathering other than it was rather dim in the bar and there was a lot of wistful laughing and I was drinking ginger ale. Stegner made us feel that we were one of the special groups he had worked with—not all had been so rewarding as we were. We wanted to believe it.

I would have some memorable correspondence with Wallace Stegner after I left Stanford and headed east. I was finishing up my master’s thesis under his direction, a collection of northern Utah stories, “a consider able dose,” he would say, of my child, adolescent, or young adult protagonists. He wrote pages of suggestions about “The Mustard Seed,” in which my young narrator almost drowned at a Mormon family re union and didn’t have a near-death experience. “I have the sense,” he wrote, that the narrator’s “experience of life is deliberately thin, that she is so young and unformed that she hasn’t examined much yet; and that this thinness is supposed to have some relationship with the experience of death, which is also rather thin.” My experience with both life and death was rather thin. I had had some luck with elliptical writing—what I left out, I hoped, would somehow profoundly suggest to the reader all the maturity and wisdom I didn’t yet have. I fooled a few people. I could never fool Stegner. “I practically never say a thing like this to any student,” he wrote, “but I have the feeling that your story here is shorter than it ought to be.” And again, “Pull aside the sheet that screens your characters, so that I see them, not their shadows.” He added bits of gossip about our group and bewailed his lack of time. “I hope,” he closed one letter, “you save a few minutes a day for silent contemplation.”

In my Manhattan apartment, on my tinny portable, I typed and re typed my western stories. Finally, both Stegner and I were satisfied. I re typed the whole collection—my thesis—after work hours on the electric typewriter in my office at Life magazine and sent them to him in a shirt box. The letter I got back was a kind of screech. “Karen!” he wrote. “You didn’t apply for the degree!” Apply for the degree? You mean, I thought, Stanford didn’t just know I wanted an M.A.? Why did they think I was there? “But I’ve been cutting through the red tape,” he continued. I don’t know how he did it—but I got the degree only three months late.

Every two years Stegner published a book of short fiction culled from the seminars. He asked me if he could include my Logan cemetery story, my own favorite of my pieces, the one I almost got right the first time. I was, of course, delighted. When the book was published, however, the story that appeared was the always-troublesome near-drowning story, “The Mustard Seed.” I wouldn’t be able to mail copies to all my relatives. Too many of them were present at that family reunion, and I hadn’t even changed Great Uncle Moses’s name.

A few years later, I returned to the Bay Area and applied for a part-time position with the Oakland Adult School. To update my Stan ford file, I wrote and asked Stegner to write a recommendation. I didn’t ask myself how he would know about my teaching skills. A couple of weeks later, I got a postcard from Scandinavia. He’d sent in the recommendation. “That ought to do it,” he said. A friend who worked at the Oakland Adult School told me that when the principal read my file, he said, “There’s a letter in here from God!” I got the job.

During the next years I taught community college students, wrote short stories during the summers, and read most of Stegner’s work—fiction and nonfiction. I heard his voice as I read The Big Rock Candy Mountain and Angle of Repose, my favorites of his novels. (When I went to the public library to check out Angle of Repose, I looked for Angel of Repose, be cause I’d misread the review, and the latter made more sense to me.) Of the nonfiction, I devoured Mormon Country, The Gathering of Zion (which I often used to enliven church lessons), Wolf Willow. The only book I couldn’t finish—and I wanted to, having just rafted down the Colorado River—was Beyond the Hundredth Meridian.

I thought of writing to him during those years, but I kept putting it off. I had accomplished so little. I wanted to report that I had written more, published more; that I had sold those Mormon stories back east, down south, everywhere; that writing about Mormons and Mormondom hadn’t confined me to the tiniest of critical audiences—those who understood the tradition and who, like me, saw the conflicts and ambiguities as universal. Like a child trying to please her father, I wanted Stegner to be proud of me. I guess I could have written him about my teaching because I have tried to teach the way he taught, and I have felt good about that. But I could never write the letter that I longed to write.

In 1987 Stegner came to Berkeley to read from Crossing to Safety at the Black Oak bookstore. My husband and I arrived very early to assure our selves of seats. I had seen pictures of Stegner, in reviews, on book jackets, and maybe I’d adjusted to any changes in his appearance, but he seemed to me to look just as he did in our library seminar room. During the question time I thrust up my hand to ask about the conflicts of writing and teaching, something he had just referred to. He looked at me oddly, then responded. Afterwards, I held my copy of his book for forty-five minutes while I waited my turn in the autograph line.

“Mr. Stegner,” I stumbled, “you probably don’t remember me. I was in the writing seminar twenty-five years ago.”

“I remember you,” he said. “You drowned!”

I laughed in surprise. I hadn’t thought of “The Mustard Seed” for years. I cleared my throat. “Do you use a computer yet?” I asked.

“No!” he said. “I’m buying up all the used manual typewriter parts in the country!”

I saw him read a year or so later, and again he seemed unchanged to me. I knew, of course, that he must be aging and had heard that he’d had a hip replaced. I even told myself that one day I would pick up the paper and read that he had died, and I sensed how sad it would make me. But I still wasn’t prepared when I saw his picture on the front page of the San Francisco Examiner that I picked up off the seat in a BART train. I was alone in the car, and I breathed, “Oh no,” and I sat and read the article.

I read and I wept—but not because an extraordinary human being and teacher had died. Even though his death was perhaps untimely, the result of a car accident in New Mexico, he had had 84 years of life, and in his fiction, essays, and history, he had pushed the West beyond its frontier fences. He had guided many younger writers towards their own important work. He had never wavered in his values: the earth and the human beings on it deserve dignity, respect, love. He honored the family: his own family, the family of writers he’d “fathered,” the bigger family of man and woman. In that hospital room in Santa Fe, his daughter-in-law told him, “You are the most moral man I know.” And at least Death came for him in the West.

I am sad because I have been able to do so little as a Mormon and a western writer. I remember his initial prophecy that Mormon fiction would never have a general audience. Perhaps Scott Card has met Stegner’s criteria of Mormon fiction with a broad American appeal; perhaps other writers, working out of and with the American West, will be able to make Mormon characters and Mormon concerns meaningful to great numbers of non-Mormons. But I felt, when I heard Wallace Stegner say those words, more than thirty years ago, that they were a challenge to me, and I know he wished me well in proving him wrong.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue