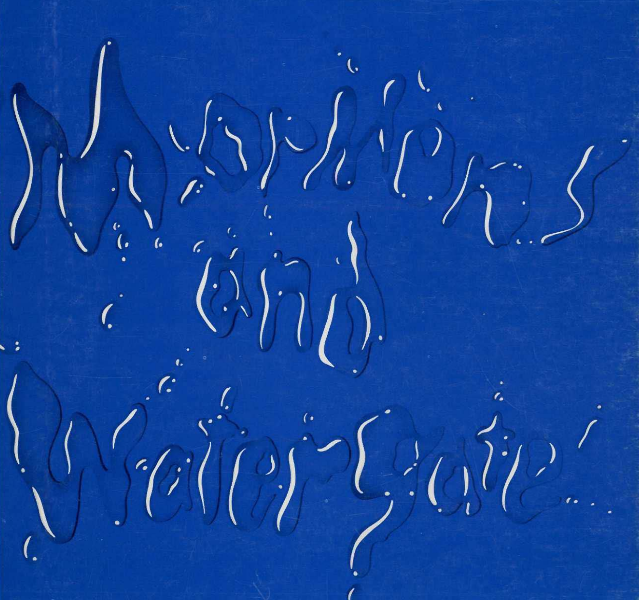

Articles/Essays – Volume 09, No. 2

Watergate: A Personal Experience

Let no man break the laws of the land, for he that keepeth the laws of God hath no need to break the laws of the land.

—D & C 58:21

. . . for we have made lies our refuge, and under falsehood have we hid ourselves.

—Isaiah 28:15

As a lawyer, I have had a professional interest in the unfolding of Watergate. Lawyers have, of course, played a central role in the saga. A staggering number of the key players were lawyers—those who were involved in the criminal activities and cover-up conspiracies as well as those involved in the unravelling of the conspiracies and the prosecution of the guilty.

Perhaps the overriding question binding the entire Watergate story together has been whether we are a government of law. This is, of course, not a new question. But Watergate has posed it to us in a new context and has given it new shapes and contours. Fortunately for us all, the prosecution and conviction of Nixon’s former attorney general and his highest aides have brought us almost full circle. The principle of rule by law and the corollary that each person is accountable to the law no matter how high his position of power have been reaffirmed.

My position as a public interest attorney brought me into closer contact with one of the most troubling aspects of Watergate—the participation of large segments of the respectable American business community in illegal campaign financing. Without the illegal participation of several of America’s largest and most prestigious corporations, many of the abuses of the Watergate scandal could not have taken place.

Years ago, Congress, recognizing the tremendous financial power of American corporations to influence elections, passed a law making illegal the contribution of corporate funds to federal political campaigns. The law also prohibits, according to most interpreters, corporate contributions to state and local elections. When politicians approach the managers of major corporations with requests for large campaign contributions, they are aware that they are placing tremendous pressures on those managers to respond by illegally using corporate funds. Much of the responsibility for the campaign abuses which have occurred in the past must therefore rest on the politicians’ shoulders. When a senator conducting a campaign for reelection receives a cash contribution at lunch from a corporate vice-president without asking any questions regarding the source of that money, it can only indicate that the senator does not wish to know the truth. While the senator has not violated any criminal statute, he has certainly participated in an activity which he must suspect to be criminal and has tacitly condoned it.

Two points should be made with regard to the fund-raising for the 1972 Nixon presidential campaign. First, in fairness, it was by no means the first time that managers of corporations had been requested to finance political campaigns in disregard of federal laws. The practice had been going on for years and, indeed, had established a pattern of accepted conduct. But there is no question now that Nixon’s men raised the art of pressuring companies for money to a new level. The stories of Maurice Stans’s list of companies with assigned shares for each, of thinly veiled threats of unfortunate consequences if the potential sources failed to produce, of approaches to companies which had important business matters before governmental agencies of the Nixon administration by lawyers representing competing companies have been substantiated. The fund-raising for Nixon’s election was by far the most financially successful in the history of American politics and it was so successful, in large part, because it was conducted with utter disregard for the criminal laws of the United States.

But this fundraising effort owes much of its success to the absolute moral and ethical vacuum into which American business has fallen. A case in which I became involved provided me with a vivid picture of the amorality of the business decision making process. It was an enormously educational, if equally disheartening, experience.

During his testimony to the Senate Watergate Committee in the summer of 1973, Herbert Kalmbach revealed some of the fund-raising activities he had carried out on behalf of the Nixon campaign. He also described how he had distributed some of the money he had raised to Watergate defendants. He stated, among many other things, that he had received $75,000 in cash from Thomas Jones, president of the Northrop Corporation, a large Southern California aero space manufacturer. The cash was delivered in Jones’s office in Los Angeles and was taken home and counted by Kalmbach. Later, this money was delivered to E. Howard Hunt, one of the original Watergate defendants, as what we now know to be one of a series of hush-money payments designed to ensure the silence of the original defendants. This “contribution” was in addition to an earlier $100,000 which Jones had given to the Nixon campaign after receiving a personal visit and request for such an amount from Maurice Stans, Herbert Kalmbach and Leonard Firestone. Jones was at a Paris airshow when the story broke, and when contacted there, he maintained that the money had come from his own personal funds.

On May 1, 1974, Jones and James Allen, a Northrop vice-president, pleaded guilty to charges of violations of the Federal Corrupt Practices Act brought by the Watergate Special Prosecutor. Northrop Corporation also pleaded guilty. The criminal information filed by the Special Prosecutor’s office told the story that the $100,000 which Jones had contribtued to the campaign and the money (either $75,000 or $50,000, depending on whether one believes Kalmbach or Jones, respectively) which he had later delivered to Kalmbach came from Northrop Company funds. In order to conceal the true nature of the funds (because it would have been criminal conduct) the money had been sent to a Northrop “consultant” operating out of Paris and then secretly returned to the United States. This procedure is quaintly referred to as “laundering.”

The same day the guilty pleas were entered in Washington, the company issued a public statement in Los Angeles describing the illegal contributions as an abnormal departure from the high standards of Northrop. The statement said that Jones was sorry for what he had done and announced that the company had decided to retain him as the head of Northrop.

About a week later, a lawyer from New York called me on the phone. He said he was a shareholder of Northrop and was most unhappy to learn that the company had been involved in the illegal activities described above. He wanted to retain the services of our law firm (The Center for Law in the Public Interest, a Los Angeles public interest law firm supported primarily by the Ford Foundation and other public foundations) and asked whether I would be interested. I said yes and began to put together a lawsuit seeking restitution to the company of all money illegally contributed and all expenses arising therefrom, full disclosure of the illegal activities to the shareholders, removal of Jones and others involved in the scheme from positions of responsibility in the company, and the appointment of an independent “investigator” in order to determine whether the contributions to the Nixon campaign were an isolated instance—a “departure from high business standards”—or part of a larger pattern. We filed the complaint toward the end of May and immediately launched into an investigation of the case by subpoenaing and reviewing company documents and taking the sworn testimony of the company officials involved, including Jones.

The investigation proved to be a fascinating, sometimes shocking, often dis heartening journey into the world of American business in the sixties and early seventies. There were times during intense and difficult deposition questioning of Jones when I would have liked nothing better than to have folded up my briefcase and gone home. At those times, Jones seemed nothing more nor less than a decent man who had gotten caught up in the pressures of the 1972 presidential campaign and had made a serious error in judgment. But as the real facts became clear, what began to emerge was a pattern of conduct dating back many years.

Long before the 1972 Nixon campaign and Watergate, Jones had made a conscious decision to funnel company funds illegally to politicians campaigning for federal, state and local office. Together with James Allen, he conceived a scheme of forwarding money to William Savy, a Northrop “consultant” in Europe and having Savy return substantial amounts of cash to New York. Savy would carry the cash on his person into the United States and either deliver it to James Allen in New York or deliver it to a third party from whom Allen would retrieve it and bring it back to Northrop’s Los Angeles office and deposit it in his own and Jones’s safes. At various times, money would be distributed in cash to political candidates of both parties. Over a thirteen year period, nearly $1.2 million was sent to Savy of which approximately $130,000 was his basic retainer as a “consultant” and approximately $400,000 was laundered in the manner described above. The remaining $600,000 is still unaccounted for.

I tell this story not because I believe it to be unique among prestigious American companies. On the contrary, it appears to have become the norm. A lawsuit brought by Common Cause forced the Committee To Reelect the President to turn over the so-called “Rosemary’s Babies” list—a list (kept by Mr. Nixon’s secretary, Rosemary Woods) containing the names of over eighty American companies which had contributed illegally to the 1972 Nixon presidential campaign. While this list has never been made public, the names of certain companies on the list are known—some have come forward and pleaded guilty (e.g., Ameri can Airlines and Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing Co.), but the majority remain silent.

During the course of vigorously prosecuting the Northrop case, I asked myself what had gone wrong with these men. Many of those involved had high reputations for integrity and honesty. All of them occupied positions of great trust and responsibility. Their communities looked upon them as highly capable and successful men. But somewhere, each had lost his “moral compass/’ to use the words of Jeb McGruder, and had seemed to drift into a philosophy of amorality with regard to business and politics.

Several factors have been at work to encourage this state of affairs. First, there are many laws on the books which have gone unenforced for years. The Federal Corrupt Practices Act is one of them. The United States Justice Department apparently decided over the years to devote its resources to other areas. Whenever criminal laws go unenforced, contempt for the system of justice results. Further, those who break the law appear to achieve an advantage over those who do not (in this case access to political influence) and go unpunished. This provides the stimulus for others to consider the advantages of violation of law as compared to the relatively minor chance of being punished.

Perhaps the most important factor in the development of the present sorry state of morality in the public and private sectors has been the philosophy that winning the election justifies nearly any means to that end. John Mitchell stated this philosophy succinctly in his testimony before the Senate Watergate Committee during the summer of 1973, but his was perhaps only the most brutal statement of a principle shared by many in politics. The spiralling costs of running a campaign for federal office have placed such an enterprise off limits to all but the super rich—and those who have been willing to accept money from American business without asking questions. More often than not, the impetus for the illegal campaign contributions has come not from the business community, but from politicians desperately seeking sources for the huge war chests they have had to accumulate.

Another element in the state of mind which lead otherwise respectable and upright men to violate criminal laws was, as I have tried to indicate, a sense that the federal campaign laws were not to be taken all that seriously. That notion was encouraged by the long standing failure of the government to enforce its own laws regarding campaign financing. Selective enforcement, in other words, breeds selective obedience. Many otherwise law abiding citizens were led into the dangerous belief that the nonenforcement of the laws was justification for non-compliance. Much of the illegality can be written off to a belief that one would never be caught, but there also seemed to be a genuine feeling that to violate laws which had never been enforced was not wrong and to punish such violations would be unfair.

I see a parallel between such an attitude and our own sometimes selective compliance with the Lord’s commandments. I believe that I personally need to exercise a greater standard of care with regard to my own selective compliance with the principles of the gospel. Undoubtedly some laws are more important than others. It is easier to repent of a failure to do some home teaching than to repent of adultery. But the consequences of consciously ignoring any of the commandments may be more serious than we can presently anticipate.

How did this case affect me? Let me be as candid as I can. I went into the case with a great sense of enthusiasm. Here was an opportunity to attack one of the most insidious evils of the modern corporate state. Here was a recognizable wrong to be righted. But it is difficult to describe what a troubling set of vibrations the case set up within me. It is one thing to intellectualize and theorize about the amorality and corruption of the world. It is quite another to come face-to-face with real people and real situations which vividly illustrate the lack of integrity and moral standards which seems to permeate modern society. It was extremely unsettling. My wife said to me that it was the first case I had ever handled which seemed to take complete possession of me for several months. I could not shake it loose. I am sure that no case I have ever worked on has affected me as deeply.

It was not so much that the men we were suing were immoral—it was the sense that morals had no place whatsoever in the market place. The considerations which went into the establishment of the illegal scheme did not seem to include a weighing of whether it was right or wrong. The thinking stopped at whether it was necessary for the business of the company—and perhaps an assessment of the chances of being discovered. Sometimes this sense of apathy threatened to overwhelm me and turn the experience into an exercise in frustration and hope lessness.

It was during the investigation and prosecution of the Northrop case that I came to appreciate anew the values which the gospel can provide anyone who determines to live by its tenets. Those values took on more than an abstract meaning. They became a practical guide to assist me in maintaining my moral equilibrium which was challenged daily by the experience I have described.

The Church and the gospel provide us with concrete experiences designed to focus our attention on the higher moral purposes of our lives. During the time I was litigating the Northrop case, I was also studying the scriptures, holding family prayer, partaking of the sacrament and doing missionary work. There is no better antidote that I know of for the erratic swings in the needle of one’s moral compass than the magnetic attraction of the Lord’s spirit which can be experienced during participation in such gospel exercises.

Through these experiences and others, such as weekly priesthood and Sunday school lessons on the life of the Saviour, I was reminded of the moral example established by Jesus during his ministry. He was familiar with moral apathy in His world. He made moral judgments and did not hestitate to exercise moral leadership when necessary. He always seemed more harsh in his condemnation of the member of the establishment who broke the law while giving the appearance of rectitude (the Pharisees) than of those who sinned but were not hypocrites (the publicans and sinners). He contended with the great conspirators of his day and overcame them by the sheer force of his supremely moral will.

I wish neither to overstate the case nor to convey a sense of moral superiority. I wish merely to convey the strong sense of personal peace and comfort I found in the gospel and in my contact with many who are trying to live it during a difficult time.

Watergate has shown us and the Northrop case has shown me in particular how easy it is to rationalize behavior which is seriously wrong. There seems to be no good alternative to a continual assessment of one’s own thinking and performance as measured against a set of standards. It is of immeasurable value to be associated with people who are engaged in that process on an ongoing basis and who can provide a sense that the moral life is possible.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue