Articles/Essays – Volume 30, No. 3

When the Brightness Seems Most Distant

“It might not be a problem,” she said to her husband before rolling onto her stomach with a pillow clutched in her arms. She was tired from crying and wished sleep would overcome her. Though her husband was awake, he said nothing. He didn’t know what to say, so he climbed his shoulders up onto his pillow and tried to stare through the slats of the Venetian blinds out into the forest surrounding their home. He couldn’t see much, the gap was too narrow and outside it was still too dark.

“Maybe it’s only in me,” she said again. “It can happen that way. Maybe it’s just Emmett. Maybe it didn’t get this far.” She tried to say more, but couldn’t. They had been talking about it all night, and all their energy had drained out of them in a steady stream. All they could do was lie on their bed as the indirect blue morning crept toward them. They hoped that in those few dark hours, the letter her ex-mother-in-law had sent from Arizona would shrivel up on itself and disappear. They thought they would wake up and find it gone. But when the light grew strong enough, they saw that it was still there, unfolded on the dresser where they had left it.

An hour earlier, just after the coldest stretch of night, starlings and cowbirds rose and began calling to one another. The man and his wife had been listening for some kind of signal that the night would be over, that they could get on with their lives, thinking it could come in something as simple as bird calls. As they lay there, waiting for the morning, they both knew that her son, Jeremiah, would rise soon, clomp down the wood stairs by himself, and take the dog out to play in the pines which ran up the hill and away from the house.

“He might not have to worry about anything,” she said, following the curve of her legs where they bent in and met below her belly. She rested her hands there, feeling the slight indentations where her body had torn itself to make room for her son. When her husband said nothing, she ran her forefinger under the edge of her pajamas and the elastic band of her garments and let it glide across the thin, crescent-shaped scar woven like a wire into her body.

The man rolled over, looked at his wife for a moment in the strange light, then rolled back and breathed out heavily. She would have to go through some denial, he thought, but ignored the fact that he would have to go through something very much like it as well. He heard his wife’s breathing and turned to watch her chest rise and fall. As he did, she was watching him watch her.

“You never asked much about Emmett,” she said after a time.

The man lay still for a while before answering. “I never figured it was my business,” he said.

“It’s okay if you want to know,” she said.

In the next room, her son’s feet slapped the floor and they both heard movement in his room. The dresser drawers slid open and shut, there were more steps, and the sound of a zipper. His door opened and they heard him walk through the hall, past their room and down the stairs.

“Is it okay if he goes out?” the man asked.

“I don’t care. It’s fine,” she said, wondering why he wasn’t worried yesterday.

They heard the dog’s loose chain and tags rattle downstairs, and, after that, the boy called to him. Then the back door slid open and they heard the dog’s toenails clicking on the wood parquet.

The woman looked over at her husband; his hands were laced behind his neck and he stared at the ceiling. She noticed that it was light enough outside for bars of shadow from the blinds to have appeared across their comforter. She tried not to think about her son’s father, Emmett, and that first marriage. She thought it was love. But ever since she’d always been confused about that. Downstairs, her son slid the door shut behind him.

He whistled to the dog through his fingers, then said, “Come on, girl. Come on.” As the woman listened to them play, she wondered why Jeremiah never asked much about his father. He was little when she left Emmett and came north, and she expected him to want to know something, but he never showed any interest. She wondered how much he remembered. Outside, a raven croaked, distracting her, and she watched its shadow fly almost imperceptibly across her corner of the bed and disappear.

“I want Emmett to know that we know,” she said after a moment. She paused and breathed slowly so she wouldn’t start to cry again. “I want him to know the worst of it.”

The man folded his arms across his chest and breathed through his nose. When he was ready, he said, “I didn’t marry you for this.” He rolled his head over and watched to see what she would do. She had nothing to say back to him. She wanted to tell him that he didn’t have to stay if he didn’t want to, that he was free to go anytime he felt like it, but she couldn’t.

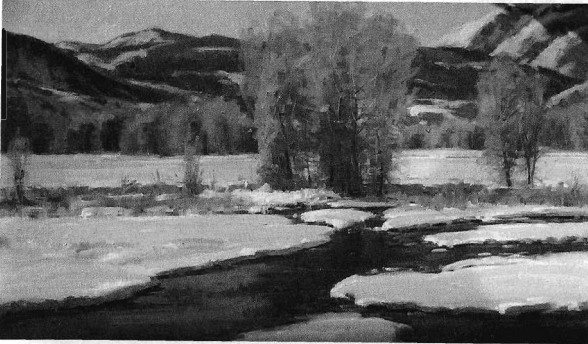

After a while the clock radio came on. The man switched it off and lay back on his pillow a minute before getting up. He crossed the room and stood at the window with his fingers separating the slats in the blinds. Through them he could see Jeremiah and the dog running together up the hill and through the sparse pines. The Uintahs stood clear above the dark line of trees. Snow still lay brightly on them this late in a very dry year, and the creeks that laced the canyons together had not yet begun to swell with spring melt. The man wondered if they would this year. He turned back to his wife; she was pulling her hair through a rubber band she had stretched around her fingers.

“He may not get sick,” she said, returning her hands to her lap. “There’s a chance that I don’t even have it.”

The man rolled his feet on the floor and drew up the blinds by the thin bundle of cords. He felt like saying something, but he didn’t know what it would be. There was no lesson in the manuals about this color of tragedy: one that comes when you’re trying your best. He ran his hands along the molding of the window sill and sash. It was stripped but unpainted. This was a project they were going to attend to that spring. They had all sorts of projects planned to restore this old farm house, but the man wondered now if he would ever get to painting this window or if it even mattered anymore in a world this different.

He turned back to her because he knew she was watching him.

She knew he had something else to say.

“This doesn’t have to be easy on you,” she said. “That’s not always the way it works.”

The man’s eyes flared, and he turned quickly to face her. “And if you test positive?” he said. “Then it’s me who buries you, not him. And who explains that to Jeremiah?” the man said, pulling back the best he could. He tried, but there was too much pent up inside. “Emmett does whatever the hell he feels like and I stay here to clean up after his messes. I go to work every day. I make sure there’s enough money,” he said, jabbing his finger towards himself. “I pay the bills and coach baseball teams and pray that I’ll have the courage not to drive down to Phoenix and smash Emmett’s head against the pavement. I. . . I—” Then as quickly as his anger came, it fell away.

“Jeremiah and I are Emmett’s messes?” she asked.

The man looked over at her and was about to answer but he didn’t. The woman noticed how small her husband seemed against the window frame when he was lit from the side and cut into sections by the panes. He opened his mouth to speak and after a few seconds said, “I take care of you and Jeremiah, not him, and he just—.” The man’s face trembled for a moment then froze. He tried to look his wife in the eye, but his gaze broke. He turned back toward the window and said, “The fact that you were ever married to him makes me ask a lot of questions I don’t want to ask.”

The woman’s chest burned. She wanted to say something to fix that, but when she looked over at him a second time and found his lips razor thin and his eyes glancing side to side like he didn’t know where to let them fall, she stayed quiet and drew her legs up into the bedclothes and waited, which had to be enough.

Clouds passed by the top edge of the window one at a time, and the ridge line behind their house took on a glow along the rim as the sun climbed higher behind it, the trees standing out against the sky one by one. From a distance up the hill the dog barked twice, and another raven gurgled and croaked somewhere on the cracked limb of a pine. Soon a clear light spilled over the ridge itself and flooded straight into the window. The man couldn’t see through any longer, but stayed facing it to feel the heat the glass threw against his face.

He will have to go through something, his wife thought, something like this. She picked up her Book of Mormon, thought of opening it, but set it back down. She rose and crossed around the bed to where he was standing and stood behind him with her hands on his back. Her husband’s muscles were tight and unforgiving.

As their eyes adjusted to the brightness, they saw Jeremiah walking down the hill swinging a stick in his hands. He seemed far away in that light, like a vision, like he was apart from everything real. When the dog caught up to Jeremiah, she nipped at the stick then stopped quickly and barked. Jeremiah stopped, looked at the dog, and shook his stick toward the animal just to tease her. After a second he drew the stick back over his head and threw it in a long arc onto the lawn. The dog crouched and sprang after it.

The man stepped away from the window and his wife.

“Are you all right?” the woman asked.

“I’m fine,” the man said as he crossed the spot where the window grid was thrown into the shadows on the floor. “I just don’t know what to do anymore,” he said.

“I don’t either,” she answered.

Back to full Issue

Back to full Issue